G. Pascal Zachary: I just want to say it’s a privilege to be here, and I’m humbled by the chance to share with you some of my historical ideas. And thank you Joi and to Ethan for including and emphasizing a historical dimension. I also want to thank the President my own university, Michael Crow at Arizona State University for his continuing support. By the way I asked for this. [Indicating podium.] The reason this is here is I can’t stand up for the duration of my talk. I’m part of the Woody Allen school of public speaking, and so I asked for this.

Finally, I want to thank Jerry Wiesner, who has words emblazoned on the wall in the lobby. Of course, Jerry like Vannevar Bush, was a seminal figure at MIT. Jerry was the Science Advisor to President Kennedy and then President of MIT from 1971 to 1980. And he reminds us on the wall—you should go look at it—that humanities and the humanist is very important in engaging technological complexity and the world of scientists and engineers. And he encourages scientists and engineers to engage the world of humanities and the humanistic enterprise.

And so we’ll turn to rebel scientists. And I’m going to make an argument in this talk that dissent is valuable not merely to establish your moral dimension or to make a moral act or moral posture. It’s essential to scientific progress. So we can’t do without dissent; it’s not an affectation.

And I have this, my clicker. And so we’re going to go right into the meat of the subject.

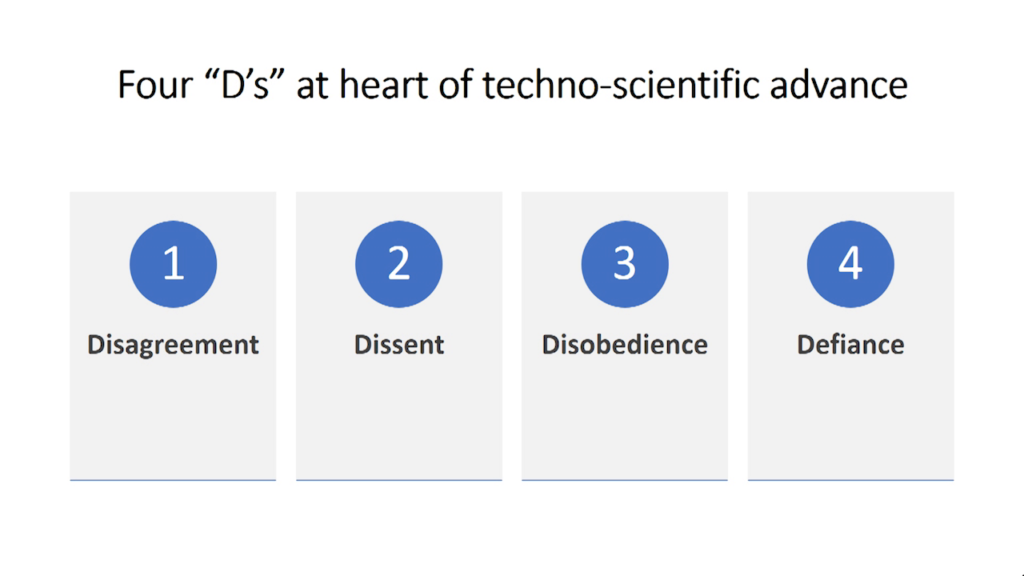

Because we want to unpack the concepts of dissent and disobedience. They start with disagreement. Disagreement is fundamental to discourse, but also to the pursuit of knowledge. If our goal as people in the academy and in the science and engineering world is to create new knowledge as well as new tools, disagreement is important.

Dissent is an act that involves arguing we’re doing something incorrectly and we want to revise.

Disobedience and defiance are raising the stakes. Because knowledge enterprise has its own rigidities and inherent conservatism. And so people often defend what ends up being wrong.

Interestingly, many scientists, and in more recent times software programmers, have argued that what they’re doing is art, it’s akin to poetry. (If I begin to fall off the stage I would like someone to just raise their hand, okay. Then I’ll know. I’ll pull myself back.) But science is an alliance of free spirits. This is not generally what the admissions to MIT or other great universities are emphasizing. They’re emphasizing mathematical prowess.

And of course Freeman Dyson, a physicist, “I believe that scientists should be artists and rebels.” Very very interesting concept. It’s a minor note in the history of science but it’s one that fits well with the notion that rebellion is central to science.

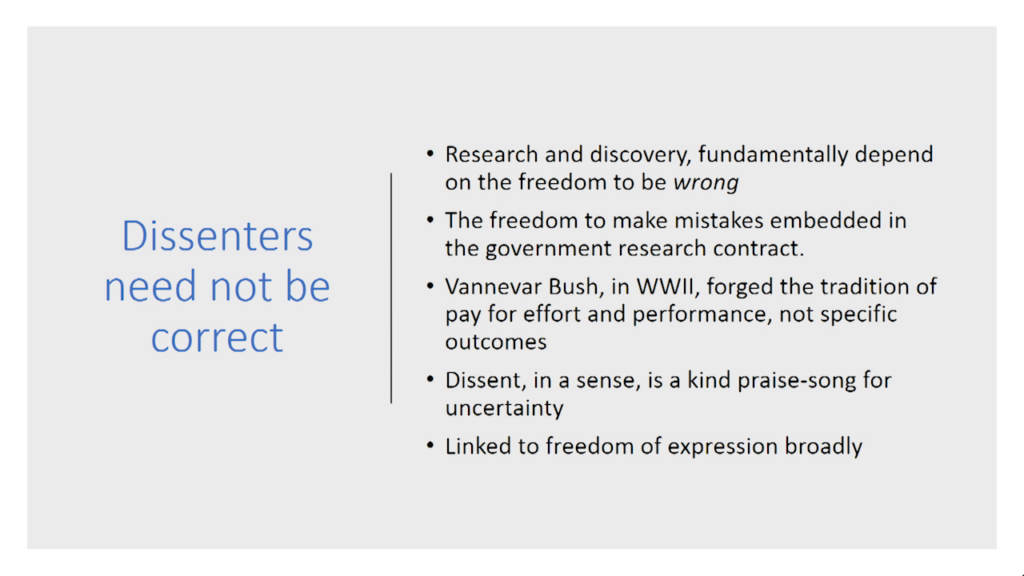

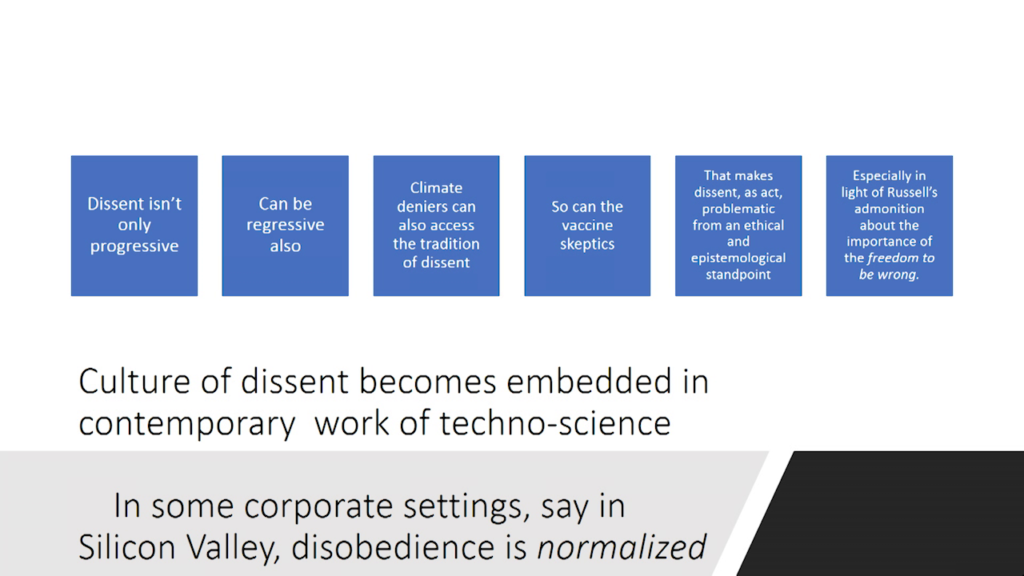

Bertrand Russell, who was a polymath a hundred years ago in Britain, he pretty much knew everything. He was also a fabulous mathematician and logician. And he talks about freedom. “Freedom for new truth involves equal freedom for error.” And this becomes problematic to us. Because often rebels are right, but often they’re wrong. And so we can’t simply presume that rebellion on its face is progressive. And I’ll get back to this.

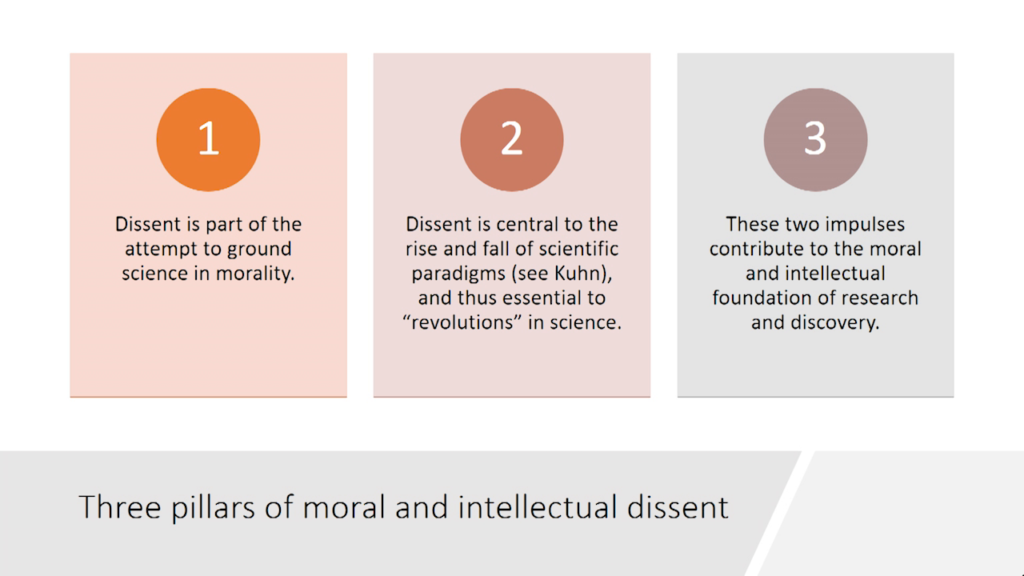

So we’ve got three pillars of moral and intellectual dissent within the scientific domain that are established through history. Dissent is part of an attempt to ground science in morality. Fighting to gain the moral high ground is often where politics plays out most dramatically.

Dissent is central to the rise and fall of scientific paradigms. See Kuhn, “The Function of Dogma in Scientific [Research],” Kuhn’s famous formulation around fifty-five years ago that just as religion defended their dogmas, scientists also did. And so revolutions are essential in science and they’re carried out by dissenters, who later of course become the pillars of the establishment.

So, these two impulses contribute to the moral and intellectual foundation of research and discovery. If we learn anything or if I convey anything, it’s that dissent is not a moral affectation. It is central to the knowledge creation enterprise.

There’s a drawing of Thomas Kuhn. And if you haven’t read Structure of Scientific Revolutions, if you haven’t come to grips with Kuhn’s ideas, whatever their flaws he’s a very very important figure because in his description of paradigms and in paradigm shifts, dissent is essential to the demolishing of old or outmoded paradigms.

Again, I’m trying to provide a functionalist justification for dissent. Because too often critics of dissenters simply say we are expressing an emotional or affective or psychological position. We’re not.

So, internal dissent, very important. That’s dissent within a discipline. It has elements of a friendly argument. One of my old friends, Dan Gilmore, sitting in the last row because he wants to be as far away from me as possible, we constantly argue but about a set of issues that we both care passionately about. But it has elements of a family feud. We both have the same ends in mind but very big disagreements about the means.

Dissent, when it moves outside of the discipline, directed at peers and elites within the field— And you often see universities and the scholarly fields are characterized by hierarchies where elites often try to promote or silence differing views. And they do it through journals and through the whole apparatus of scholarship. Often these are professional only. So, someone may be a vociferous dissenter who’s a physicist but actually they’re a mild-mannered person, and they never complain about anything even at home. It’s a very professional type of dissent.

So sometimes rebellions are carried out within scholarly fields, and over the course of twenty or thirty years you see a complete change in emphasis, in what’s taught in textbooks, in what’s taught in university undergraduate introductory programs. And that is the apotheosis of dissent, when dissent becomes the new conventional wisdom.

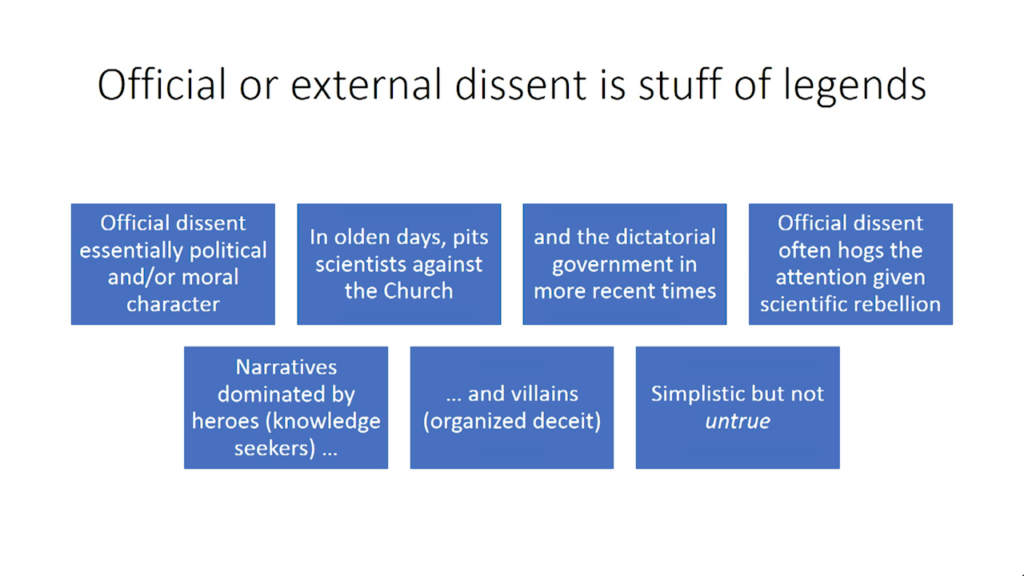

Official or external dissent, what Joi was referring to about dissent against government, dissent against tyranny, dissent against religious authority. It is the stuff of legend and often Hollywood. The moviemakers hit upon these struggles because they are pitting, often, a character, an individual who suffers for their beliefs, shows bravery, and either triumphs or doesn’t. But ultimately, in the movie, somebody on their side wins.

So in the olden days we had science—knowledge-makers—pitted against the church. In this case we’re talking about the Catholic church in the West. But there were other religious institutions in other parts of the world that had a similar role. Dictatorial governments in recent times. I mean, I’ve done a lot of studies of World War II, and in the 1930s Hitler talked about ridding Germany of Jewish science. Jewish physics, in particular. He associated physics with Jews and wanted to expel Jews from the field and he talked about their ethnicity rather than the content of their work. And so you’ve seen this in recent times, too.

Official dissent often dominates the story of dissent. There is a lot of tyranny that occurs at the sub-state level. And we’ll see a little bit of that later. So narratives are dominated by the heroes, the knowledge-seekers. Or the organized establishment that is committed to deceit or at least to wrong ways of looking at the world. This makes for good narratives, and actually is largely true. It’s largely supported by the historical record.

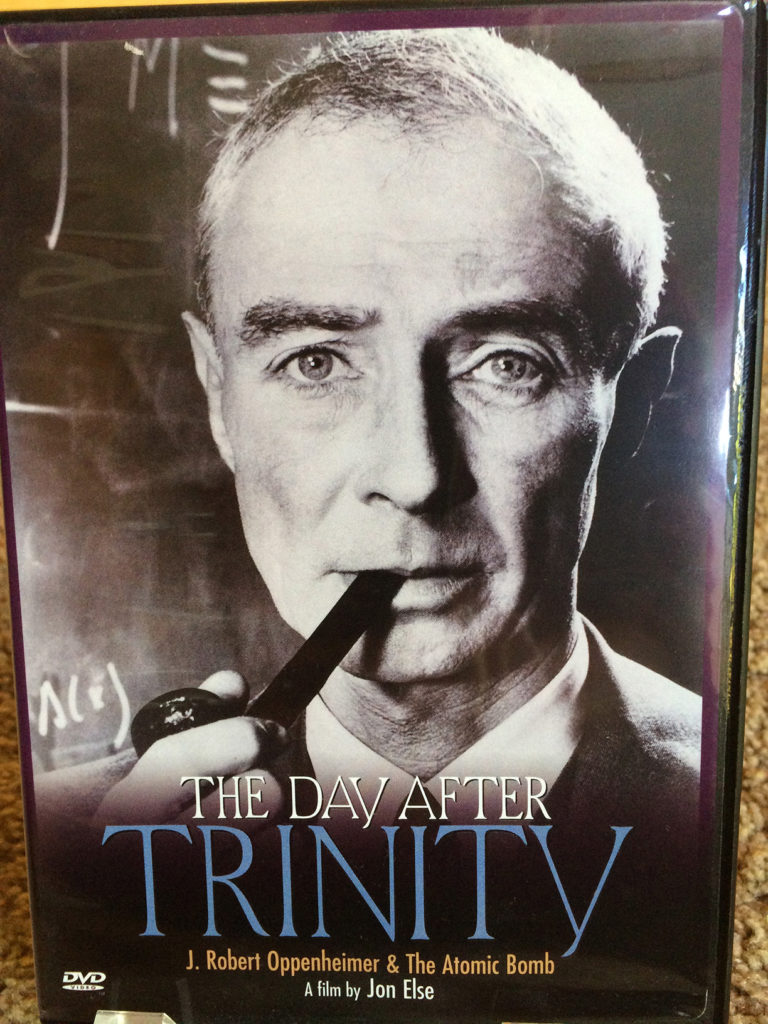

Robert Oppenheimer, anguished in this photograph. By the time of this photograph a broken man. One of the great American physicists of the 30s. Was the scientific director of the Manhattan Project. And then in the 1950s ran afoul of a faction within the military that was angered over his opposition to developing the hydrogen bomb. Oppenheimer himself— And this is often part of the story of science, of even scientific rebels. They can be very vain, very egotistical. And rather than quietly withdraw, Oppenheimer sought a public fight in which he was humiliated and retired to Princeton to nurse his wounds and became, in this era of McCarthyism, a hero. But possibly a hero for the wrong reasons.

But you see how the power of images and the documentary by John Else, the incomparable John Else, The Day After Trinity. Well worth viewing if you want a vivid illustration of the cost of dissent and also how dissent can be misunderstood. Oppenheimer was no pacifist. He just thought atomic weapons were enough.

This is probably the most contentious thing I’ll say. Hopefully my use of complex language and being on the stage will undercut your sense of resistance to my message. But one thing that I’m really trying to get across is we presume that dissent and rebellion in science is progressive, but it’s often reactionary. This adds to the complexity of our problem.

Russell told us the freedom to make mistakes is central to the scientific activity. When Vannevar Bush, who negotiated and constructed the government research contract that allowed the federal government to directly contract with university professors and independent scientists, the contract says, “All you need to do is give us a good effort and we’ll pay you. If your outcomes don’t match what were promised, no big deal.”

Well, no other field works that way. You don’t sign up to build a bridge for the US government and tell them, “We’ll see how it goes. If it falls down we still want to get the full payment.” But when you’re doing research under contracts that were designed and devised in World War II and continue to this day, what the federal government insists upon is only that you really tried. That the scientists really showed up for work. If they don’t deliver what was promised, the money still comes. And scientists have argued that they need that freedom to drill dry holes, to make mistakes. They can’t be pressured into delivering when delivery isn’t possible. That might promote deception, say. And you do see that in countries that have very repressive regimes. Their scientists sometimes do a lot of incentive to lie.

So, dissent is in a sense a kind of praise song for uncertainty and that the enterprise of science is very linked to the classical liberal ideal of a society where freedom and individuality count for a lot. And I think a lot of you in this group are very imbued by a sense of your own freedom.

So just a brief tour in the time that remains of the historical roots of rebel scientists. Because your legitimacy as rebels today and dissenters today in part depends upon the legitimacy gained by past dissenters and rebellions.

So Galileo, found guilty by the Inquisition in 1663. He wants to advance the claim that the Earth and other planets revolve around the sun.

Interestingly, the mother of his dissent is technology. So we we have science and engineering and technology as an instrumentation. And Galileo, like many great scientists, his career is transformed by embracing a new tool. He quickly buys a telescope, I believe developed in Holland, and he improves it. And through improving it can get the sort of evidence that he needs.

And this is really often where scientific dissent springs from. It’s new tools that expose new data. Because evidence-based claims are what the dissenters and the establishment share. Everybody says they’re making evidence-based arguments. The dissenter often comes along with a new tool and says, “Look. This is evidence we haven’t seen before. We have removed the cloak over the unseen.” And so Galileo’s real achievement was technological.

Another dissenter who deserves more attention and of course got it in his lifetime ultimately, Joseph Rotblat, a physicist from Poland. Went to England then joined the Manhattan Project. Amazingly, despite all of the ferment and regrets after Hiroshima, only one physicist quit the Bomb project. And it was Joe Rotblat and it was in secret. You didn’t tweet when you quit things in the 1940s. Nobody knew. He snuck out of the projects. But in the 50s, so about ten years after Hiroshima, Einstein and Bertrand Russell form group called Pugwash. And that group, Joe Rotblat essentially becomes the staff director, the actual organizer.

Rotblat’s dissent, and his proactive activity to build bridges between physicists in the Soviet Union and physicists in America, there was a belief that if these physicists understood each other better, maybe they would act in concert to slow the arms race.

Over time, Rotblat was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. And his career and the life of Pugwash— which still exists—is a testimony that dissenters can build lasting institutions and what starts as a secret act of defiance can become later a public one.

Here, very close to home, Norbert Wiener. Very controversial, complex figure. A prodigy. In 1946 he gets an inquiry after the War ends. Of course, the US has won. They now occupy Japan and Germany. Wiener had helped with artillery. There was a big problem with making missiles more accurate, meaning hit their targets. Their targets were people or machines. So the idea was to make the bombs better at killing things and destroying things. Wiener by ’46, ’47, he feels he shouldn’t be helping this anymore. There was a problem, though. This type of missile accuracy was central to the world of computation that was emerging.

And so he says that he won’t help any military projects or receive any money from the armed services. So he insists on the ultimate power we all have, and that’s to say no. To refuse and withdraw. We all can always say no. And sometimes saying no is our only and best option.

But Wiener fell prey to a paradox which he never acknowledged, which is we don’t always know what our work can be used for. I was talking to Ethan this morning and I just mentioned that we could be working, he could be working, on a wonderful game to educate young people using the Web, and some different kinds of interactivity. And then unbeknownst to him, a military research team takes these ideas and maybe even directly applies them to a very different problem. So Wiener’s refusal to work on military problems really does fall in the category of moral gesture because he can’t know for sure whether or not any of the things that anybody’s working on will be militarily relevant. But it doesn’t diminish the importance.

There was in the 40s, in the 60s, periodically, and you see it in the computer community, software programmers, this notion that you know, echoing Marx, “workers of the world unite!” If all the physicians get together, if all the software programmers get together, if everybody who works on Facebook says no, they can stop something. It’s just very very difficult to get that kind of unity.

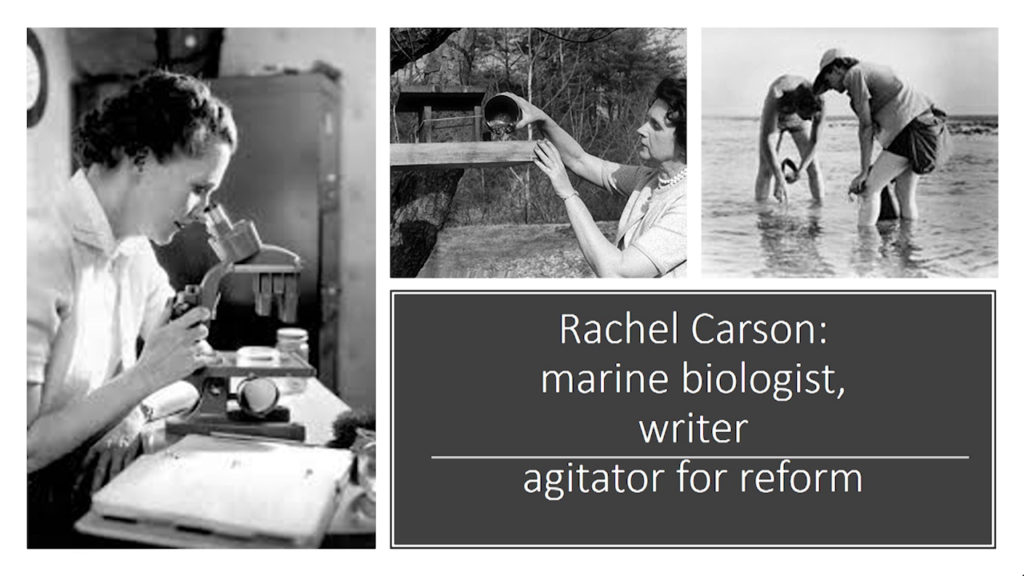

To return to the singular voice, one of the most important singular voices of the 20th century in science was a marine biologist who would have gotten her PhD—she got a Master’s at Hopkins. She needed a certain level of employment and pay. She went to work for the federal government in the Fish and Wildlife Service. And working for the federal government, something many of us aspire to do, right? To become a federal bureaucrat. What a goal. But yet, as a federal bureaucrat she incubated two great books that were both best sellers. She had a boss that helped her—also a federal bureaucrat—helped her get into The New Yorker. And she becomes an important voice for environmentalism generally, but in particular industrial pollution.

So in the 50s, oceanography and marine biology come together in [Rachel] Carson. In her dissent against mass spread of industrial chemicals. There were all these famous films of children bathing themselves in DDT and the excessive use of chemicals. She wasn’t against chemicals, she was against their excessive use. And she also is very concerned about exploding hydrogen bombs in the ocean. It’s astonishing to me because I’m only 61. I’m not 101. And yet in my very lifetime, our government has gone from polluting our planet on a massive scale that’s inconceivable to anyone under 30, a thousand above-ground explosions of hydrogen bombs, to professing that they’d like to protect the environment and save it. In a mere 50 years. It’s astonishing. So the world really has changed a lot.

Roger Revelle was a military oceanographer during World War II. He was a naval officer. He had been a leading oceanographer at Scripps Institute in San Diego. During the war, he helps. He was an officer in the Navy. After the War the Navy takes up the task of becoming the major source of funding for physics, oceanography—what were then called the hard sciences.

Because he’s a reliable reserve officer now and the head of the leading institution—along with Woods Hole one of the two leading oceanography institutions in the US—he’s put in charge of something that went under the name of “Bravo.” It was just a simple experiment. The Navy was curious, if we blew up a coral reef with a hydrogen bomb what would happen? They really wanted to know.

They assembled a team of a hundred scientists under Revelle. They were hoping that what would happen is, their hypothesis was, you know how when you take a bath and then you pull the plug and it all goes down the drain? That’s what they were hoping. You would go boom, and then it would come down, and then it would sink to the bottom of the ocean. And it would never be touched again. It would just sit there.

And they thought that Revelle and his team would find that. Instead Revelle and his team found something really really different. They did two things. They created a new set of tools to follow the movement of water to the oceans. And that led them to the certainty that the radioactive H‑bomb debris spread all over the planet.

And then second, because they were interested in the relationship between temperature in the atmosphere and movement in the oceans, they in 1957 published a paper, Revelle and a man named Hans Suess— And that’s not Dr. Seuss, by the way. It’s a common mistake— Hans Suess, publish a paper in 1957 that is the beginning of the discovery of global warming. And it’s all done because a scientist says, “I am not going to do what the Navy wants.”

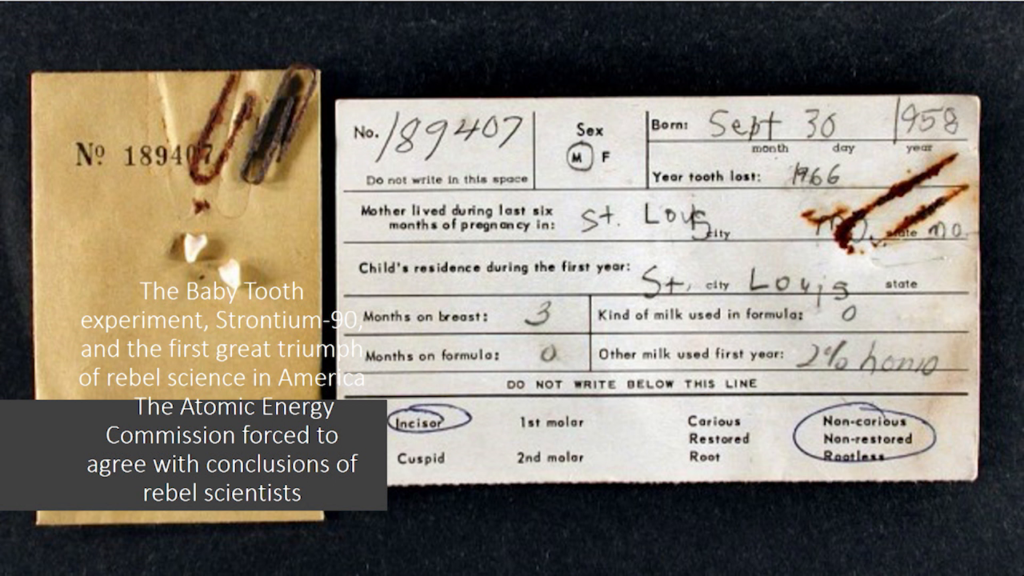

Another example in the same period, Barry Commoner, a biologist, also concerned about the effects of hydrogen bombs, comes up with an interesting and the first important example of citizen science. Asks mothers around America—and he was especially interested in involving women in this movement to face the cost of the H‑bomb. Asked them to send the children’s baby teeth as they fell out.

He got thousands and thousands of baby teeth. And in fact these are some of the actual records. And those baby teeth astonishingly contained strontium 90. In the teeth of babies. And of course by deduction, of adults too. Strontium 90 can only occur from a hydrogen bomb.

When the Atomic Energy Commission is confronted with this evidence, they do something that shows in the face of dissent the state can crack. And they crack. They say, “Commoner, the science is solid. There is strontium 90 in your babys’ teeth.” They just said like many people say today, “Don’t worry about it. And the teeth fell out, huh. So let’s move on! Let’s watch Dick Van Dyke Show.”

But that was a major victory. And as the establishment begins to accept dissident science, of course the dissenters grow stronger. And by the end of the 60s the relationship between many academic scientists, not just government scientists, and scientists at MIT, and the Vietnam War becomes a source of controversy. There’s a really excellent book, Becoming MIT, that was published on the 150th anniversary of MIT. It has a great chapter by Stuart Leslie on the Vietnam War. And the Vietnam War changes the way MIT thinks about social responsibility and by extension the way academic scientists think about classified research. Many academic scientists now refuse to do classified research, and while it’s crept back on campuses, it’s much much reduced.

So the culture of dissent today is embedded in techno-science, meaning in engineering and science together in the research enterprise. In some settings like Silicon Valley where I spent many many years, in northern California—I still have a home there—disobedience is normalized. Oh, if you’re going for a job at Google or Facebook you’ve got to say you’re an anti-corporate. You could start doing all kinds of things that look like you’re insubordinate. And that is…you know, we see it in vaccine skeptics. How difficult it is for the left and the right to figure out who are these vaccines skeptics? Robert Kennedy’s son is one of the leaders. Of course he was a great liberal. And then freedom to be wrong. That’s really really important.

One final point. I’ve got one minute. Do engineers and scientists have a different approach to dissent? I think the historical record shows the answer is yes. Many engineers think of themselves as employees. And they do what the employer says or they work within the constraints of the employer then maybe they have a personal life where they might dissent.

When there was a March [for] Science in DC, was there a march for engineering? No. AAAS supported the March for Science. IEEE, electrical engineers and the most important engineering association, did not. So we see a very different approach to dissent.

So dissenting scientists and engineers are part of the landscape of research.

And in the last seconds I’ll just say that the future of dissent and disobedience, which many of you are committed to, should pay attention to history. Because history may show you patterns. How they play out so you can anticipate better what your struggle might face. And second, it gives you legitimacy. And it shapes your expectations for social responsibility and good. Because dissenters range across the spectrum between Wiener saying no and on the other end replacement activities. Rachel Carson had a whole different idea of modern life.

So let me close on that. I really appreciate your attention. And I hope during the break I can answer some questions individually for people. Thanks a lot for listening.