Jeffrey Warren: Public Lab is a community and a nonprofit, and we do environmental work with people all over the world. And we really try to address environmental issues that affect people. What we do we call community science, and I think some people sometimes think of Public Lab’s work as translating science to the public in a sense. But I really think it’s not exactly it. We work a little on the inside, a little on the outside.

And what we try to do is actually distinct from citizen science. Citizen science is often defined as people assisting scientists in the collection of data or in doing science, and it’s admirable, it’s good work. But community science is about placing scientific issues that affect communities—which are often environmental issues—at the center of the discourse, and communities at the center of addressing some of these problems.

And community science involves people not only in data collection but in all aspects of the scientific method and the scientific process. And we specifically—at Public Lab we support communities who are investigating local environmental issues that might affect them and their health: oil spills, chemical spills, effects of the oil and gas industry.

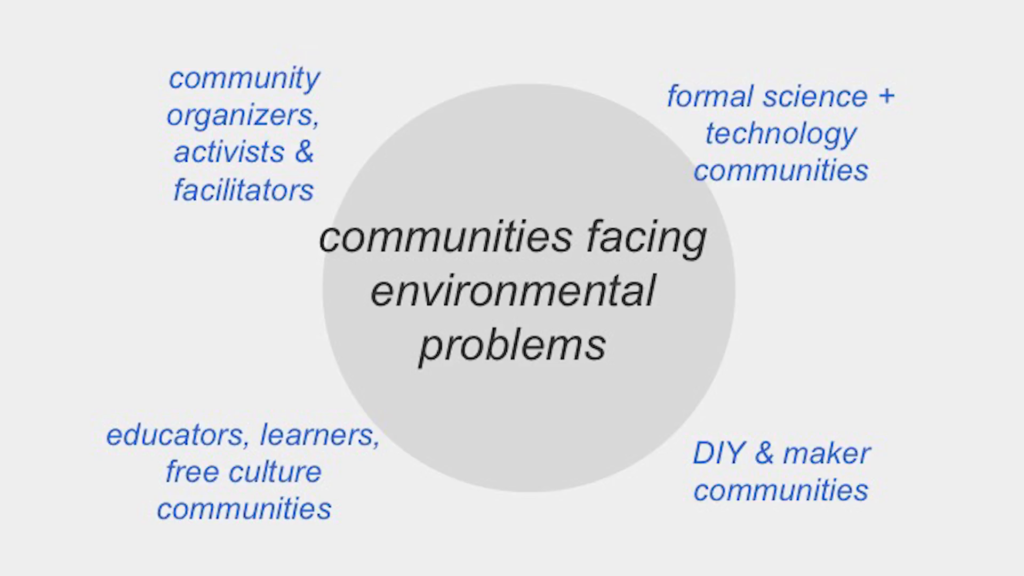

And through this work, we get a lot of questions about how knowledge is produced at all; like in general, in the broader sense. And really specifically how expertise functions. Who gets to ask the questions or act on the answers? Our model is to place the communities that are facing problems at the center of the work, but also to engage for example formal science and technology communities, DIY maker communities, educators, learners, free culture activists, community organizers, facilitators.

And as you can imagine, that involves a lot of cultural work. So, bridging gaps. I mean, people speak different domain-specific languages. People aren’t used to thinking of how other people approach topics or work through issues. And a lot of this is really about equity. It goes beyond open source. Because in a sense open source, or open access…the idea that everyone should have equal access to it, is not as powerful or deep an idea as the idea that people have been prevented from having equal access and so we have to do proportional work to make up those gaps and to bridge those gaps. And Max Liboiron gives a great talk on equity versus equality that you should watch instead of listening to me on the subject.

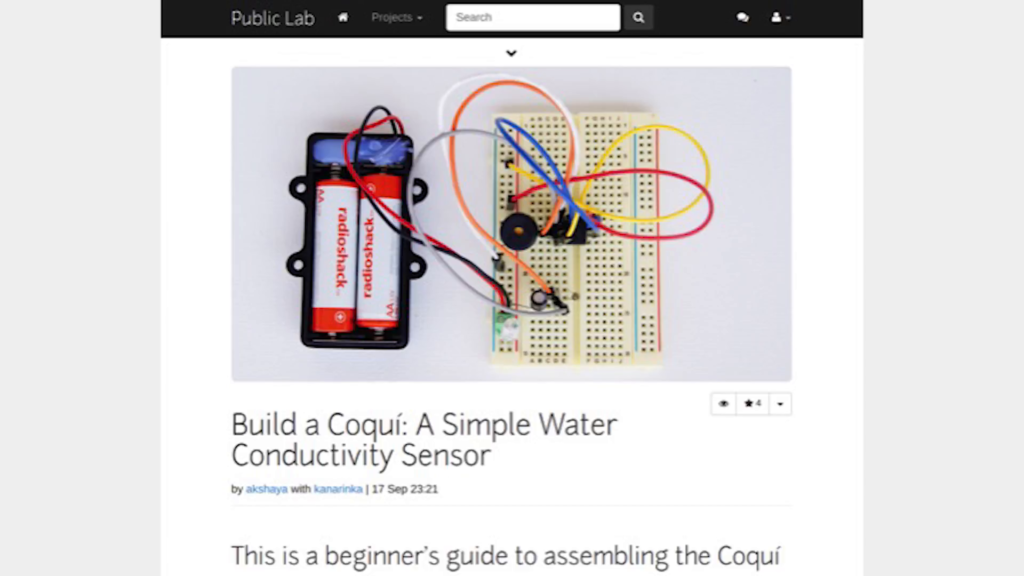

And so a lot of this ends up being work not only on making science findings accessible but its methods, its tools…who actually participates in it. The structural issues. And this means both making more accessible on-ramps into science, environmental science in particular, but also challenging what’s possible, or what questions are asked by leveraging peer production and using an open-source collaboration model. Engaging people who have not been included in science processes, but people who have key and critical questions.

So a lot of people may ask like, why do it yourself? Like why go through the trouble of inventing new tools or inventing new processes? Like, why can’t we just scale science up so that everyone can do it, like make it more available and then you know…but basically unchanged. And if more people can do it then we’re okay. So it’s more like an educational model.

And I think it’s because…for all that they can do, experts often have a pretty narrow conception of where the public might become involved in science. Public dissemination of science, for example, or data entry. Or where science might lead us. Sandra Harding talks about how the public should be more involved in selecting problematics; choosing the problems which we should engage in. And communities that are facing something like an oil spill are well-placed to be driving what kinds of questions science should be addressing and what kind of evidence we should be collecting to achieve greater environmental justice. And then of course cost is another barrier, I think. So we have to address some of the issues of like, building your own tools, because the existing tools are too expensive.

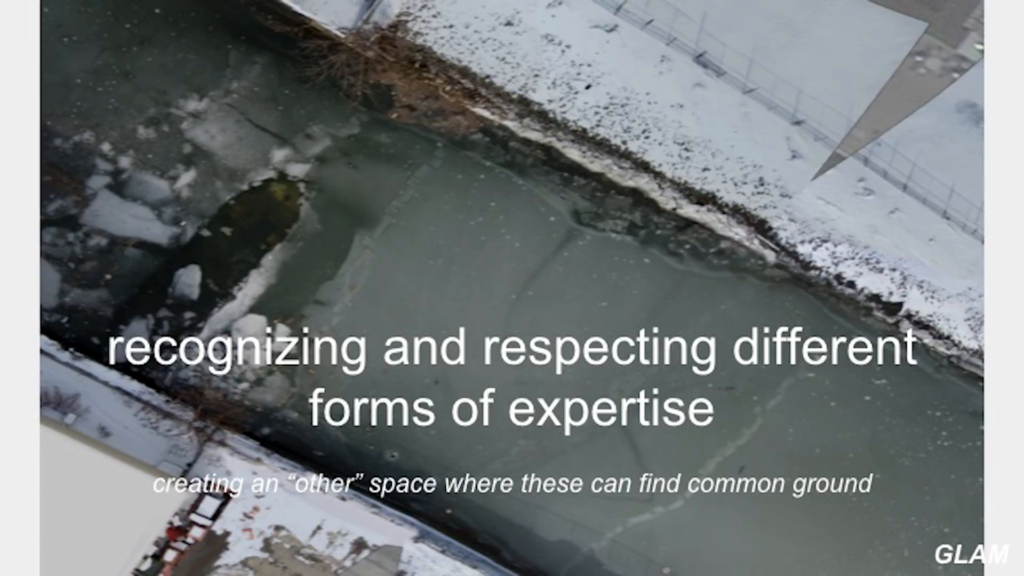

Just for an example, part of recognizing and respecting different forms of expertise— This is actually a picture from the Gowanus Canal. A balloon blue mapping project. So a lot of what Public Lab does, one of our biggest projects is balloons mapping; taking aerial photos with balloons. And this one revealed an inflow into the canal that the EPA Superfund process had not discovered, and an engineering survey of the site had not discovered. And it was local activists who who knew the canal, knew the patterns, they knew to go and take a picture when it was frozen because that little channel coming out above the word “and” is melted ice from that inflow.

And so there’s local expertise that is really powerful that we want to reify and amplify as part of our sort of embrace of what Sandra Harding again calls “strong empiricism,” the idea that like we double down the idea of evidence-based knowledge, that it can be more equitable through that approach.

Demystifying is another way we approach this. I wanted to note this. It’s one of our better-known projects that’s a papercraft spectrometer that you can build. You can download the plans, it’s all open-source. But part of the idea here is to break down what instrumentation means through a hands-on practice, through artifacts, through the selection of materials.

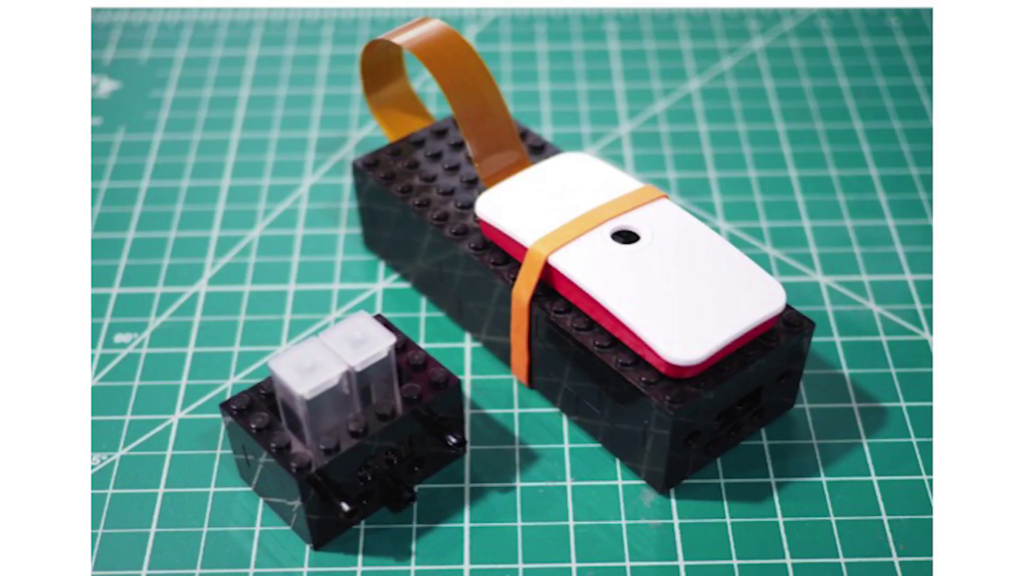

This is another version of that cat that’s actually made out of Legos. So we speak through the choice of materials. We speak through the language we use to describe these things. And that reflects our community values at Public Lab.

And I think just to wrap it up, one of the projects I wanted to highlight was one where people are making DIY microscopes to analyze samples of respirable silica dust that results from frac sand mining in the Wisconsin area and other places. And really like, what is a microscope? And so to try to demystify and break that down, create on-ramps into that. And to enable people to build their own cheap microscopes that are good enough to actually see particles at the scale that respirable silica occurs at, we have a basic microscope kit that we distribute, and it’s building on a lot of other open hardware efforts, collaborations, and so forth.

So that’s just one example of how we do it. But I think the gist of this is that do-it-yourself means changing how we produce knowledge, not just taking the existing framework and scaling it up but actually looking at some of the structural issues that prevent people who most need a more robust environmental science framework to have access to it and to have agency and the ability to direct it.

Thank you very much.

Further Reference

Gathering the Custodians of the Internet: Lessons from the First CivilServant Summit at CivilServant