J. Nathan Matias: In the first half of today’s summit, we’ve heard Tarleton describe some of the challenges we face around moderation. And we’ve heard Ethan and Karrie talk about ways that people working from outside of platforms, outside of companies, can use data to understand complex issues and create change. But how can we be confident that the change we want to create is actually happening? Now, that’s a driving goal behind this idea of citizen behavioral science, and something that we at CivilServant want to invite you to join us in.

Now, in a series of short talks we’re going to share examples of some of our past and upcoming work, alongside examples from our parent organization Global Voices. But I want to start by saying something about how we go about our work.

I want to start with this example that has been appearing in the news. People have been publishing claims by ex-Google employee Tristan Harris that turning your phone gray can reduce the addiction that he says we all have with our smartphones. Nellie Bowles wrote in The New York Times, “I’ve been gray for a couple of days and it’s remarkable how well it has eased my twitchy phone checking.”

Now, Bowles did a smart thing. She decided to do a test and collect evidence. And whenever we have a question, whenever we have a concern about the way that technology might be impacting our lives—it could be discrimination, it could be the policies that we cocreate—collecting evidence is a smart move. Now how could we do that systematically?

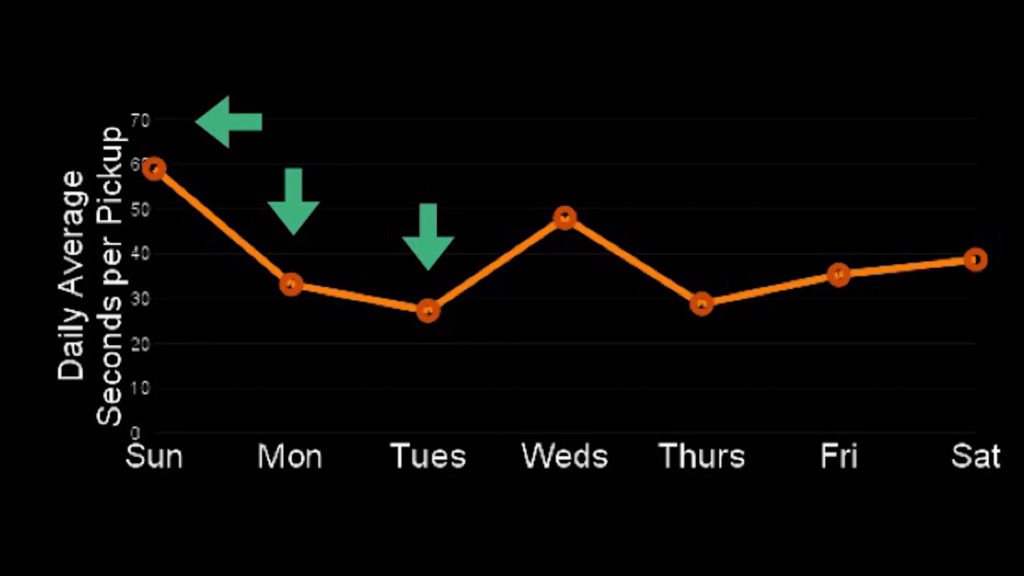

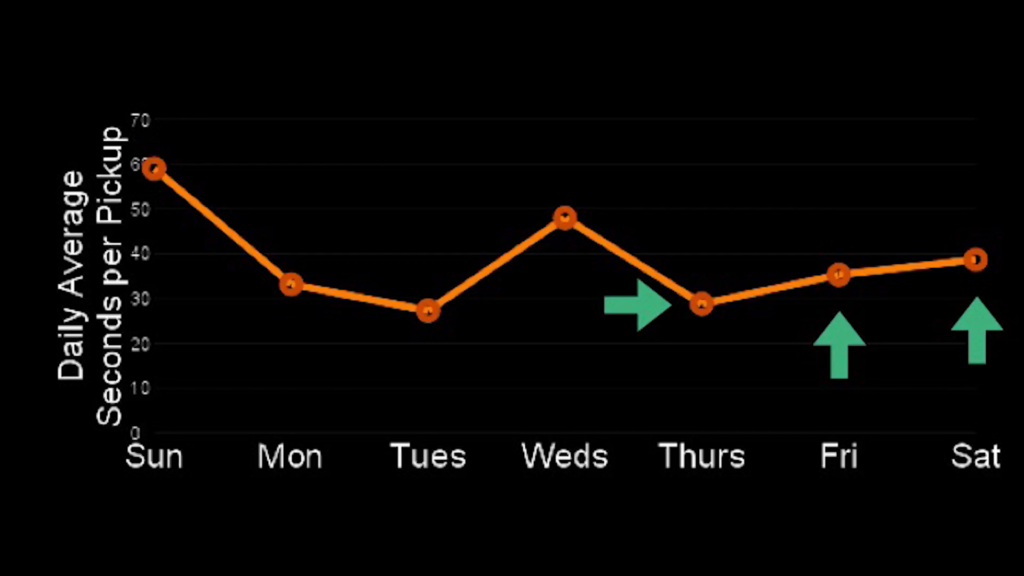

So here is a chart of the number of seconds that I typically look at my phone every time I pick it up. Because when you want to do a test, one of the first thing to do is figure out what to measure. So, I wanted to know if addicting colors were influencing my attention. I would expect that I would be looking at my screen for longer. And that maybe if I turned my phone gray, perhaps I’d be spending less time with the phone in front of my face.

Now, measurement doesn’t necessarily have to be a number. I could keep a notebook, or I could have conversations with people. But in this case I chose to report it like this.

Now, I want to ask you to imagine if I decided to turn my phone gray on Monday and then observed it over the next two days. I would have looked at this and seen, oh well actually this is impacting my phone usage and I’m actually looking at the phone as little as half as much, every time I pick it up, if I started on Monday and compared it to how much I was using my phone on Sunday.

But now let’s imagine that I actually decided to start on Friday and did a gray phone challenge then. Well I might look at the data and think well, actually turning my phone gray makes me look at my phone even more. It’s the luck of the draw of which day I decided to look at my phone and which day I decided to start observing. It could lead me to a completely different conclusion based on chance.

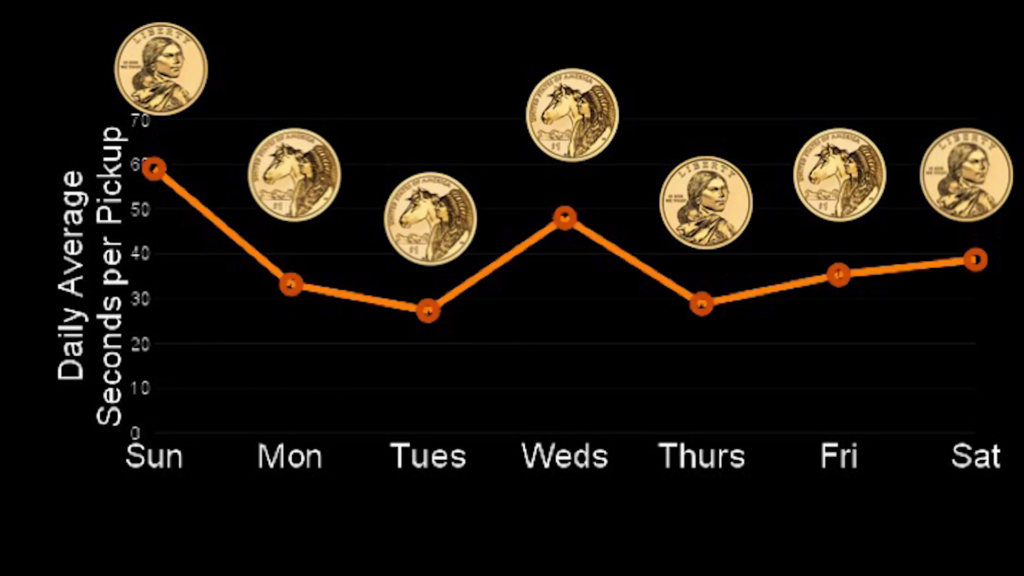

So, when we do experiments we try to control for that factor. We flip a coin. We say well, I’m going to flip a coin on Sunday, I’m going to flip a coin on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday. And based on pure random chance, I’m going to then see how much I end up using my phone on that day. That’s a way that allows us to make sure that there’s no outside influence. Because it’s possible that when deciding when to start my own gray phone challenge I might have unconsciously been thinking, “Well I’ll wait to start until I have the time to do something different.” And that might in fact have been a day when I was using my phone less.

And so randomized trials and other kinds of experiments allow us to do a comparison that’s not based on the kinds of luck of the draw but gives us a truer or a confident picture of the effect of the thing that we’re looking at.

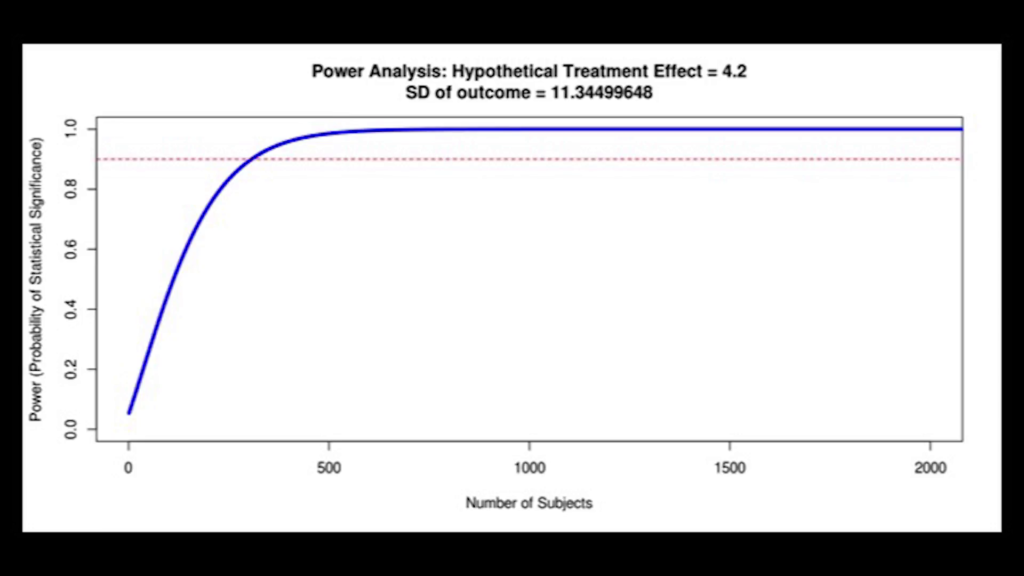

Now of course, if I just looked at it for two days I might be less confident than if I’d observed my behavior over a longer period of time. With each new day, my confidence in the result can increase. So let’s say for example that I am addicted to my phone, and that switching my phone to gray reduces the time I spend every time I pick it up by four seconds.

Now, someone with my phone usage would actually have to flip a coin and monitor my phone usage for about 315 days, over a year, to have a pretty good picture of the effect on my behavior on average. That’s a pretty inconvenient sample size. But if other people join me it’s possible to answer that question more quickly. Like if fifteen people joined in, each of us might only have to look at our data and do this experiment for three weeks.

So when we think about how each of us individually might try to make sense of this online question or an online risk, there are benefits that we gain by working together, benefits we gain by asking questions with large numbers of other people. And in fact, this is something that I’m doing. I’m really curious about this claim by Tristan. Are our phones addicting us? Is the color in those phones influencing us and keeping us glued to those phones? And I’ll be launching something soon called the Gray Phone Challenge that invites anyone to find out if your phone is influencing your behavior in this way, and if so, how. So look out for that.

The reason I bring that up is that what I just described is something called a randomized trial, an A/B test, where like A is your phone has color, B is your phone is gray. And that’s a method that is especially useful for finding out the effect of an attempt to create change. It might be a question about a moderation policy. It might be a question about whether we’re seeing discrimination from an algorithm. But this basic method is something that we can use in a wide range of contexts where we know at least that there’s something valuable that we can measure.

And that’s one of the methods that’s at the heart of the CivilServant nonprofit, which organizes people online to collaborate to find discoveries about the effects of different ideas for creating change online. This is a project that started in my PhD here at the MIT Media Lab and the Center for Civic Media. And now, thanks to the Media Lab, Princeton University, and the funders I’ve mentioned—the Ethics in AI Governance Fund, the Mozilla Foundation, and generous donors—we’re being able to take CivilServant and turn it into a new nonprofit that can support the public to do two things: to ask questions that we have about how to create a fairer, safer, more understanding Internet; whether we’re moderators on Reddit, YouTube channel operators, people on Wikipedia, bystanders on Twitter. We can all find ways to collect evidence and find out what works for the society we want to see.

And the second part of what CivilServant does is to support people to do this auditing work. To both evaluate and hold accountable powerful entities for the role of their technologies in society.

In the next set of talks we’re going to hear from a set of communities that we’ve worked with over the last two years. And I want to say something about how that process has worked on the Reddit platform.

CivilServant, in addition to being an organization, is a software platform. You can think of it as a social bot that communities invite into their context to collect data and coordinate research on effective moderation practices.

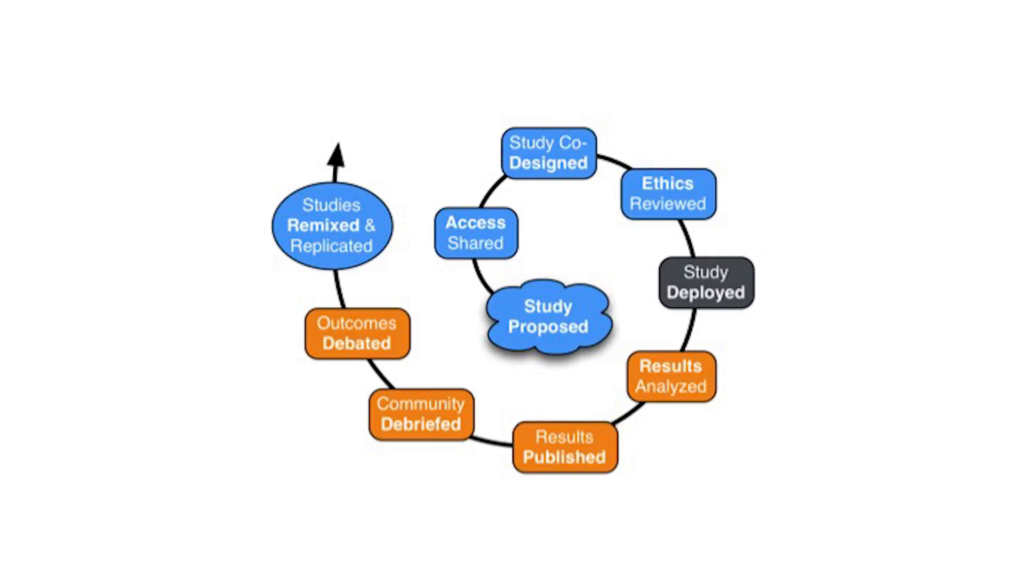

So the research process starts when we have a conversation with the community. Usually our research agenda is shaped by the priorities and questions that moderators and communities on platforms like Reddit have. And then we have a conversation about what they want to test. At that point a community typically invites our bot into their subreddit, into their group, to collect data with their permission, to start observing and measuring the things that we’re interested in. We then discuss and debate what the right measures are and arrive at a description and a process for asking the question that they have.

I should note that CivilServant works in such a way that our ability to operate in the community is completely subject to that community’s discretion. If they want to end the study, they can just kick out our bot and we end the work. So we try to do work that is accountable to and shaped by communities.

We then run that research by university ethics boards and make sure that it’s approved in that way. And once all of that has happened, we start the study. We often prefer that there be some kind of wider community consultation; that’s not always possible. Then we start the study, and it might run for a few weeks, in some cases it might run for a few months.

But ultimately, we complete the period. You know, it’s that case where I’ve observed my behavior for 315 days or I found fifteen of my friends to make it much shorter. We get to the end of the study, and we analyze the data. We do various statistical methods and arrive at some answer. Does changing your phone to gray reduce your screen time? Does banning accounts in a certain way or responding to harassment in a certain way change people’s behavior in the ways that we expect? There are a wide range of questions that you’ll hear from in just a moment.

And then we also have a public conversation, where we let people know here’s what we did, here’s what we found. Do you have questions? Do have critiques? Is there further research that we need to do, other debates and questions we have to have about the ethics of this work? How can we be more transparent about our own research? And that often leads into conversations within those communities about how they should make decisions and change what they do based upon what we discovered.

In the case of my own phone behavior, at the end of this study I’ll have a decision: do I want to change my phone to only show me gray, or do I want to see colors? And that’s a conversation about values that we as researchers aren’t necessarily in the best position to make a decision on, but we want to put evidence into your hands to make the best decision that you can.

And the cycle doesn’t end there. After we’ve completed a study with one community, we’re then in a good position to then support other people to do similar research. If we’ve already built the software for a study, it’s really easy to set up something similar in a new community or a new context and gather more evidence. Because what might work for me—I might be more distractible than someone else, and rather than just take my word for it or data from my experience, you might also want to learn for yourself. That’s what researchers call a replication.

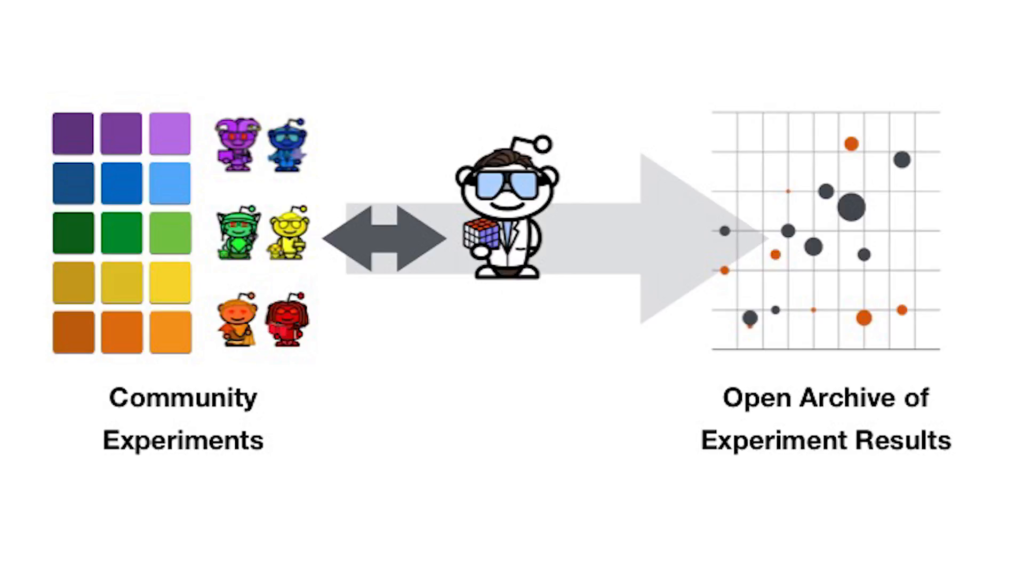

And one of the ideas behind the CivilServant nonprofit is that as we support more and more communities—more citizen behavioral scientists—to ask these questions, all of the results of what we discover will be shared to an open repository where anyone can read the results, and also where anyone can do their own experiment and build up a larger picture of where and under what conditions, and exactly how the different ideas in moderation and other areas of online behavior work.

So CivilServant, as I said, has received funding from a number of sources. We’ve hired our first staff. We’re going to be announcing a number of new positions in the next months. And over the next year our hope is that with your help, with the help of people across the Internet, we’ll be able to not just create a trickle of these studies but really scale the pace of knowledge around a wide range of questions for a fairer, safer, more understanding Internet. Our kind of goal for now is to see how close to 100 new studies we can achieve in the 2018 calendar year. And we’re hoping that you will be part of that conversation with us.

So next up, to give you a sense of the kind of research that we’ve already done and will be doing, I’m going to ask up a round of researchers and communities who are going to tell us about what we’ve done together, and also what our peer organizations have done. So if you’re one of our lightning talk speakers, now is a good time to queue up and be ready to to come on stage. I’ll just ask you to come up, and when you finish, if you can step down and the next talk can commence.

Further Reference

Gathering the Custodians of the Internet: Lessons from the First CivilServant Summit at CivilServant