Piper Below: Hi, my name is Piper Below. I’m a professor of human genetics at Vanderbilt University in the Vanderbilt Genetics Institute. And I’m one of the head mods of r/science. This is going to be such a short talk that I’m gonna mostly let Nate here run the mic. But I’ll be up here and if you want to ask me questions later I’ll be around.

Nathan Allen: My name’s Nathan Allen. I’m user “nate” on Reddit, Principal Scientist at the Sigma-Aldrich corporation. I’m group leader for new product research there.

J. Nathan Matias: And I’m Nathan Matias, the founder of CivilServant.

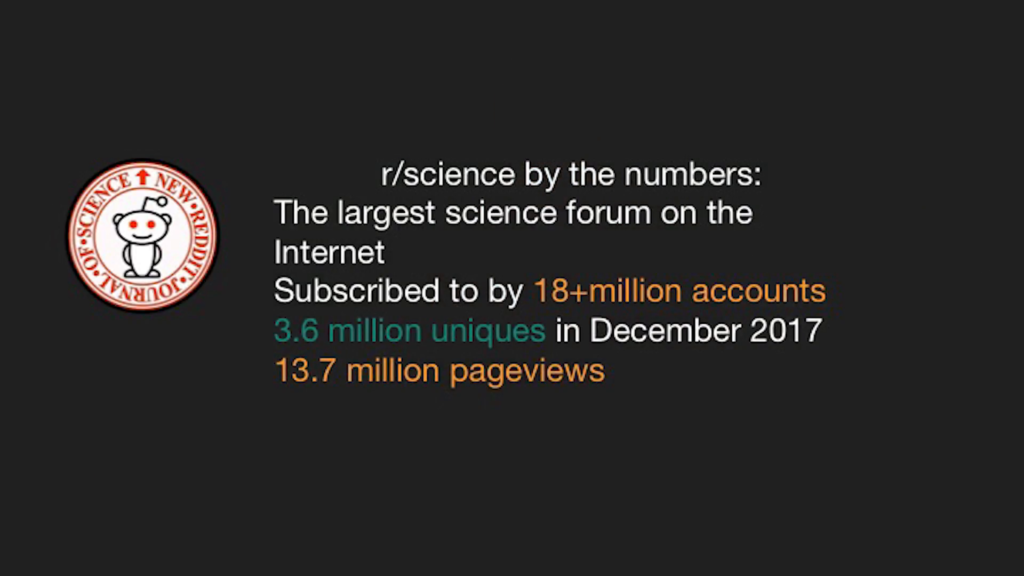

Allen: Alright, so. A little introduction about what r/science is. So r/science is really the largest science forum on the Internet. We say that we have more than 18 million subscribed users. For a point of reference, the total combined subscriber base of the top ten newspapers in the United States is around ten million. So we’re rapidly approaching twice the subscribed user base of all of the newspapers in the country. We had about 3.6 million uniques in December. And about nearly 14 million page views. So, pretty big forum. We deal with a lot of traffic. And we’ve adapted to deal with this in many ways.

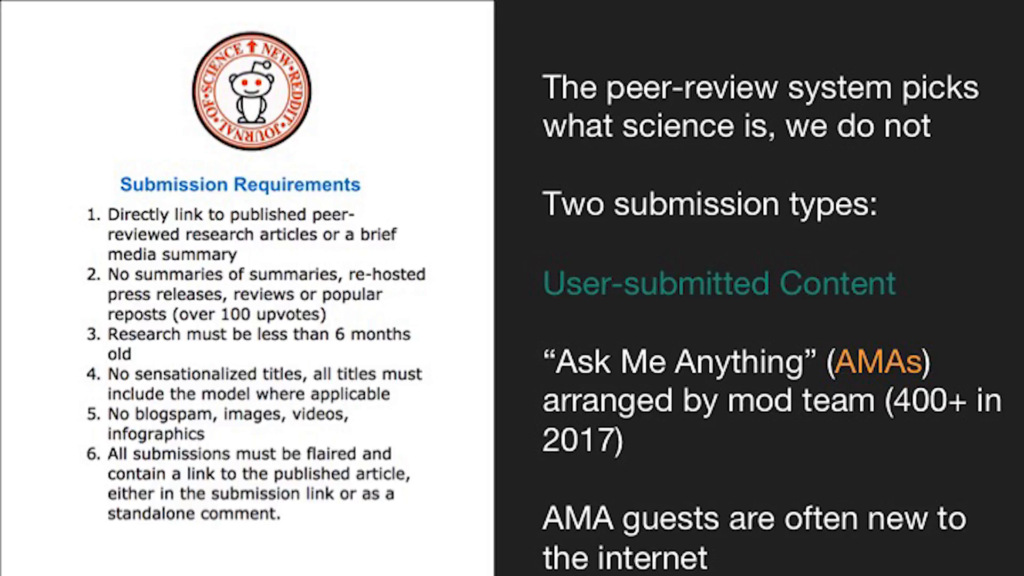

There are two basic types of submissions that you get on r/science. There’s user-submitted content. These are summaries of peer-reviewed journal articles; things that summarize a journal that was recently published. We put in hard binds to determine what those are so we are not deciding what science is. Science is decided by the journal referees in the peer review system. If it gets published in a legitimate peer-reviewed journal and somebody writes up a summary of it, you may post it and we will allow it.

The other type of content we allow are AMAs, where we go out and we recruit scientists who have enough prominence or interest to speak directly to the general public. The aim of these is to disintermediate the relationship between scientists and the general public. We recognize that the trust in institutions is waning in our society, but institutions are made up of individuals. As people understand that individuals make up institutions their faith in institutions can be redeveloped to a point at which we maybe will have faith in scientific institutions again. This is our long-term goal.

In order to accomplish this however, if we ask substantial guests who are of prominence and not really used to the Internet, there’s a great deal of hesitation to come to the Internet and speak. Nobody is going to show up for their own lynching, after all.

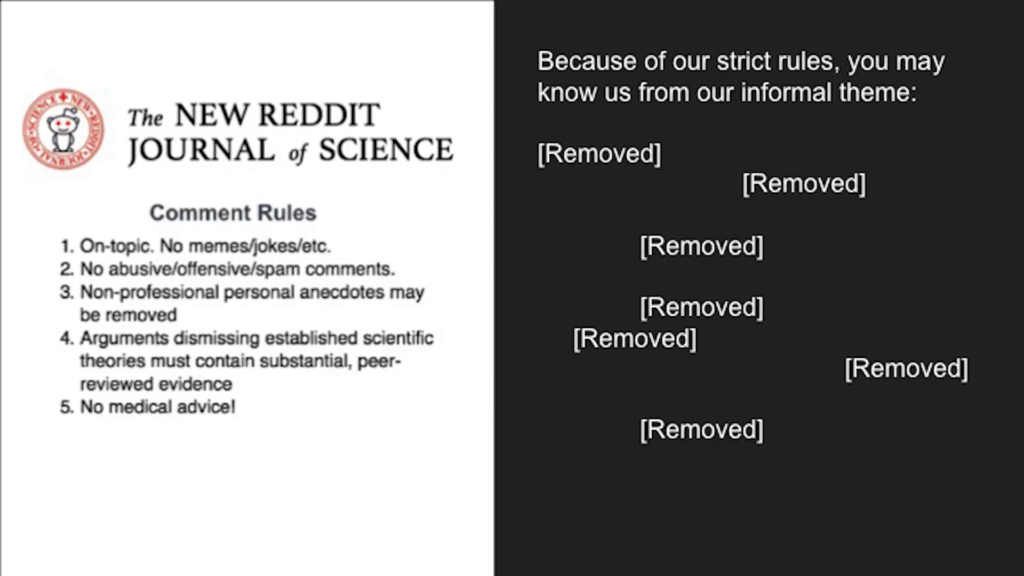

In order to do this, you may recognize the state bird of r/science. We have rules. And we enforce these rules. We…brutally enforce these rules sometimes, and we’ve kind of become known for that.

Audience member: So basically like AskHistorians.

Allen: Uh, not quite that bad… But, you know… They’ve found out the ultimate solution. [?] is an AskHistorians mod.

So. We have the largest moderator team on Reddit by far. No one’s even close. The ModEveryone subreddit has 50% less moderators than we do. We have more moderators than the top fifty subreddits on Reddit combined. We have almost double that number. We have a lot of moderators.

So, we have the bandwidth to enforce our rules brutally and without any mercy. We don’t want to do that. We want people to want to not break the rules and interact with our community in a way that’s constructive and civil. We want to shape our community with cultural norms and suggestions. And this is what led us to work with Nate Matias to test how we can influence that, because these things are difficult to get a handle on. So let Nate tell you about what we did on that.

Matias: So, just about two years ago, the moderators of r/science came to me and asked this question, can we can we post the rules in a way that actually prevents people from violating them and getting into trouble with the moderators? We were also worried about a side-effect, that it might push newcomers away at the same time.

Now, the kind of theories behind this that come from social psychology are ideas about social norms. That when we post rules to the top of a community, we influence people’s beliefs about what’s approved and what’s disapproved by the people around us. And so we thought that by posting the rules to the top of discussions, we would influence those beliefs and consequently influence people’s behavior.

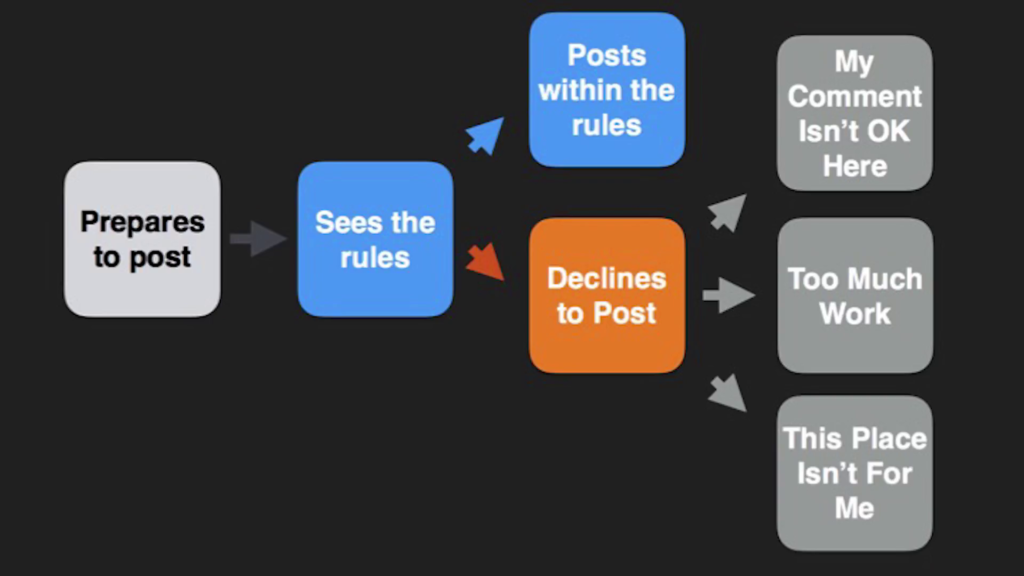

We were also worried about some other side-effects. That someone might come to the community, they might have prepared a post, they might see these rules, and then decide not to participate at all. Either because they felt like their comment wasn’t okay there. Because they felt that maybe it would be too much work to alter what they were going to say to follow the rules. Or because maybe they felt that this isn’t the place for me. And as a community that wants to broaden who has a scientific conversation with scholars, with other people who are curious about science, that would not be a good outcome.

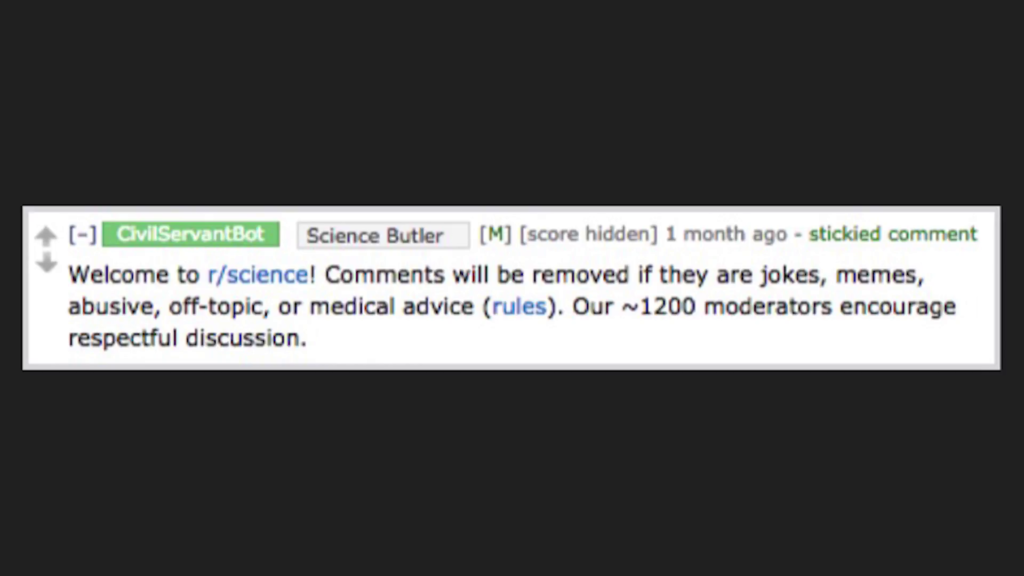

So with that in mind, here’s what we did. We created a set of messages that we used a piece of software to post to the top of discussion threads. So when someone shared a link to a journal article or hosted a live Q&A with a scientist, we would use this bot to randomly assign some discussions to receive a message that welcomed people, explained the rules, described the consequences, explained that lots of people agree with the rules. And that there were enough moderators to enforce them. All things that have kind of ties to theories in social psychology.

And then we measured a bunch of things to see what the effect would be on whether first-time commenters would post things that followed the rules. And also looked at the impact on the percentage of first-time commenters.

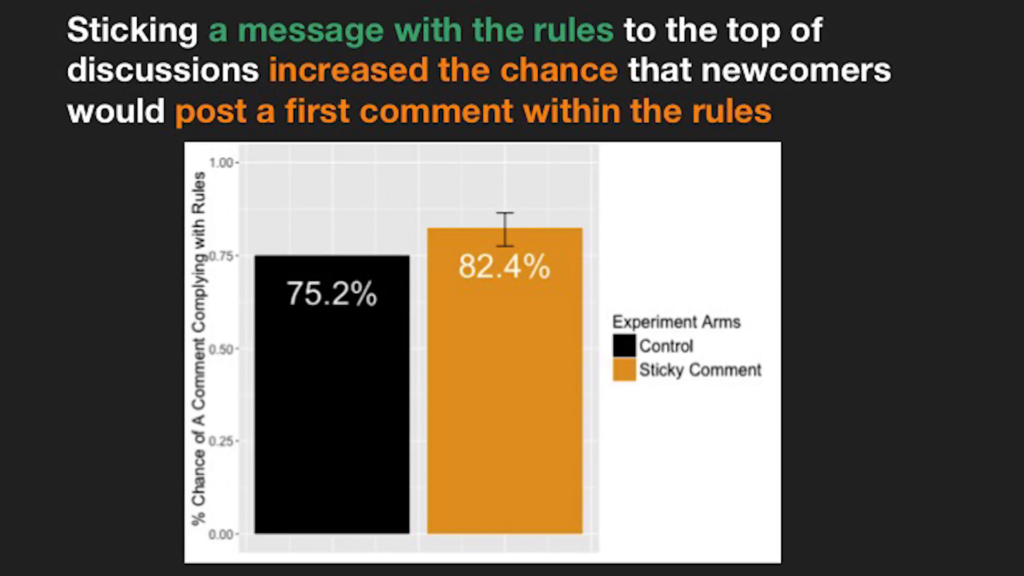

So, we found when we conducted this test in 2016, we ran it over 2,200 discussions including many live Q&As. The study ended up including over 20,000 newcomer comments. And we found that as you can see, posting this message to the top of discussion actually did increase the chance that newcomers would participate in a way that complied with r/science’s rules.

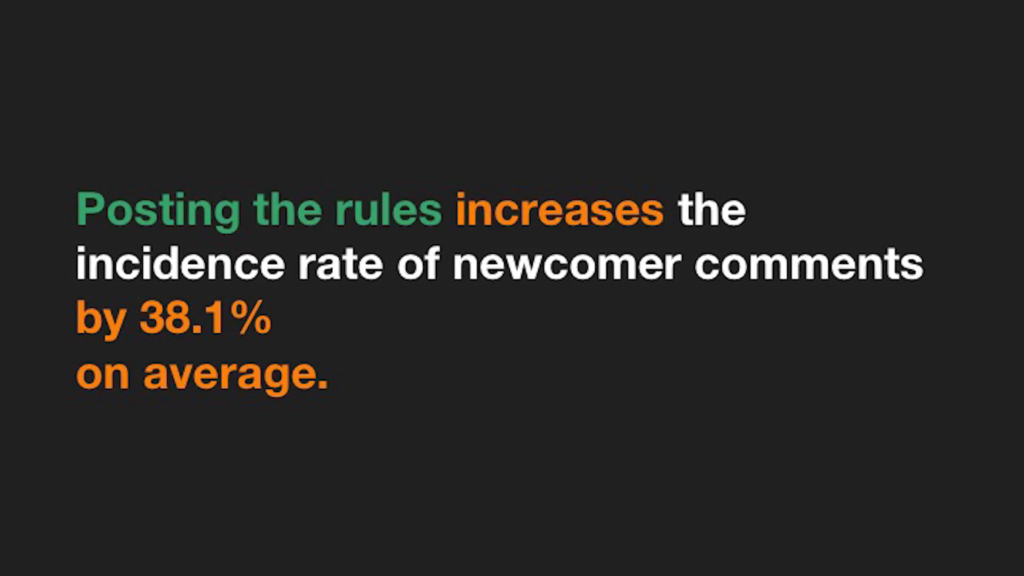

And we also found that, contrary to our expectations that it would maybe push people away, that it actually increased the rate of newcomer participation. That when people saw that the rules were there and they would be reinforced, more people participated in those conversations. In fact, at the volumes that r/science was at at that time, on average the community could prevent over 1,800 newcomers a month from some kind of unruly behavior. And would also gain over 9,000 first-time commenters a month, just by posting the messages to the top of the community.

And this study didn’t just stop with r/science. It ended up being picked up and adopted by a number of other platforms. The Discus platform which is used on lots of sites across the Web has pointed to our research as a motivating factor behind features that they’ve released to tens of thousands of websites across the Internet. And our friends at The Coral Project have cited our research as one influence in their wider efforts to reengineer how comments happen online.

For us, we’re glad when people take what we’ve learned in one context and hope that people will learn from them. We’re also especially excited when people respond to our findings with skepticism and say, “But what about my context? Will that really work here?” And our answer at CivilServant is “We don’t know. That’s a great question to do your own study on.”

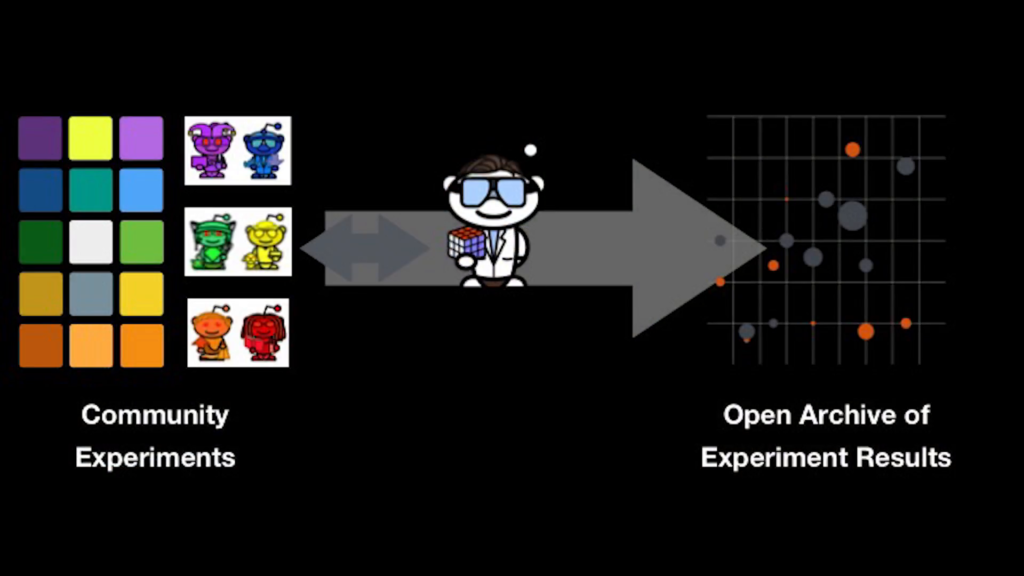

And that’s why we support replications, where communities can do their own research and then contribute to a shared pool of knowledge. So if you’re interested to test ideas about harassment prevention in your community and on your platform, we’d love to talk. And you should feel free to reach out to the moderators of r/science later and chat with them about the amazing work that they do. Thank you.

Further Reference

Posting Rules in Online Discussions Prevents Problems & Increases Participation at CivilServant

Gathering the Custodians of the Internet: Lessons from the First CivilServant Summit at CivilServant