Anne: Croeso i chi gyd. And I bet there’s only one in the audience who just understood what I said. That was a warm welcome to you in Welsh, and it’s really great to hear so many different languages here [at] the 30c3.

That’s where we are in Aberystwyth. That’s twenty kilometers north of the only place in Europe where civilian and military drones can be tested in civilian airspace. And that’s crucial for future policing techniques with drones in high density environments. We’re also fifty kilometers north of the town where Manning went to school when he was a teenager. So we’re at the periphery of Europe, but also at the heart of some of its major debates. That’s a perfect example, I would say, for Deleuze and Guattari’s theory of the rhizome of non-hierarchical entry points into culture, and in our talk we’re going to bring some of these entry points into creative opposition.

Since first we drafted this paper, we have seen in both Germany and the UK major examples of crowd activism. Here in Hamburg last weekend, and earlier this month in London, where amazingly all three elements of our talk “Policing the Romantic Crowd” came together spectacularly. This was the scene in London, where thousands of students were protesting against police presence on university campuses, and Richard was especially pleased to see a Romantic book, Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792) among the book shields carried by Book Bloc. This reminds us that a powerful rhetorical tradition of civil liberties and gender equality has its roots in Romantic art and poetry.

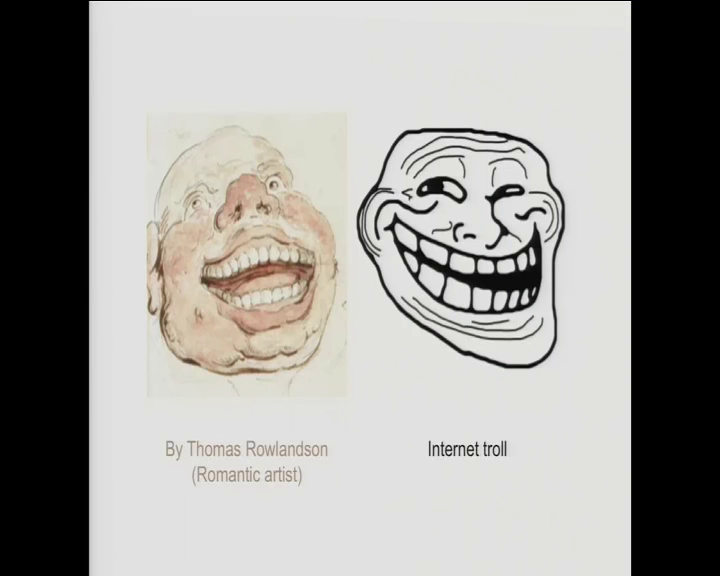

Richard: But our point isn’t that Romanticism has already had all the insights into surveillance culture, the culture of the nose. That said, it does appear that the Romantics saw the Internet coming.

Okay, maybe not the Internet, but certainly peer networks of communication based on trust. We have to be careful about distinguishing between mere analogies linking the Romantic period to our own age that maybe don’t have any useful analogs, and those that do have some continued operational relevance. Because it is the case that Romantic writers like John Keats, Mary Shelley, William Wordsworth, philosophically modeled and to some extent thought through many of the debates and issues that we’re currently having as we seek to shape the contours of our future societies.

These writers lived in the age that first imagined total surveillance. This is the age of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, published in 1791. So at the very least it’s valuable to remind ourselves where some of our ideas about surveillance and privacy and crowds and particularly the policing of rhetorical and discursive space have come from. We’re going to go on a journey into the Romantic crowd. What in Romantic slang is called “the push,” a bit like the Kaffeeschlange outside Saal 1. On the way we’ll be meeting Romantic poet John Keats, a couple of dandies riding velocipedes, a certain Victor Frankenstein, and two crowds that managed to be in the same place at once.

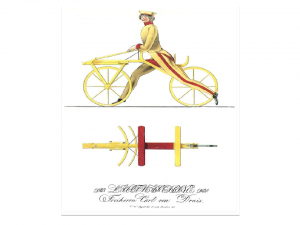

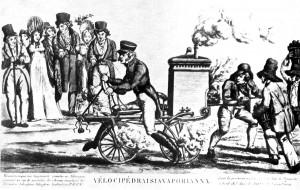

Spring 1819, and German cutting edge technology arrives in London in the form of Karl Drais’ laufmaschine. These velocipedes were popular among the Romantic geeks of the day, well-dressed dandies like these two, very eager to try out new gadgets, although the rudimentary steering mechanism sent many of them into hedges or tumbling into duck ponds. John Keats, in a letter from March 1819, dismissed this new technology.

The nothing of the day is a machine called the velocipede. It is a wheel-carriage to ride cock horse upon […] They will go seven miles an hour. A handsome gelding will come to eight guineas, however they will soon be cheaper, unless the army takes to them.

So Keats is ridiculing Drais’ invention as “the nothing of the day.” But that word “nothing” disguises a techno-ethical anxiety. Anticipating that the army would take to them, Keats, who was part of a circle of anti-government activists is worried about potential military applications.

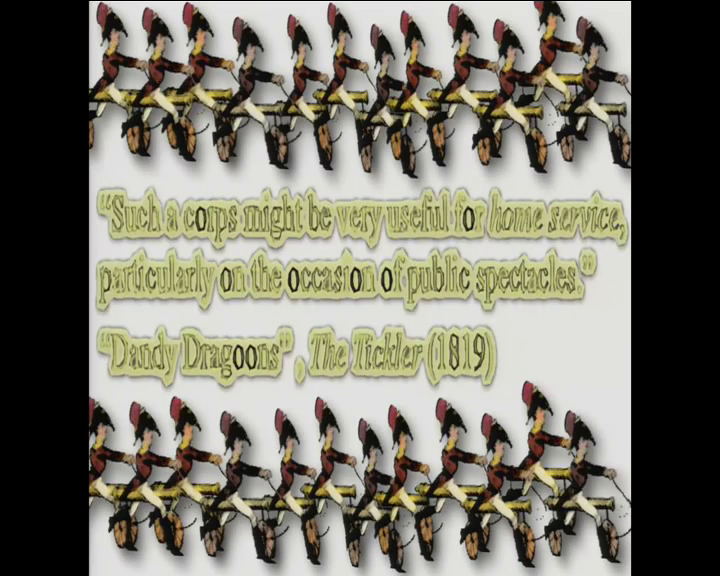

Anne: Not quite like this design of the first police motorbike from 1818, and certainly not like Mega-City One’s take on the velocipede. But nonetheless a potential revolution in policing techniques. Keats wasn’t the only one to worry about the army taking to them. On September 1, 1819, a popular magazine called The Tickler (they had great names back then) conjured up a vision of an entire corps of velocipedites, or dandy dragoons. And here they are riding cannons.

Such corps might be very useful for home service, particularly on the occasion of public spectacles.

“Dandy Dragoons”, The Tickler (1819)

What The Tickler is talking about here is policing demonstrations, but that date September 1, 1819, is actually significant. It was just two weeks after mounted police riding real horses and armed with sabres had brutally dispersed 60,000 protestors on St. Peter’s Field in Manchester. That was the infamous Peterloo Massacre. Thirteen people were slashed or trampled to death, and hundreds wounded. One eyewitness was so appalled he founded a new liberal newspaper called The Manchester Guardian, today just The Guardian.

But for all the humor, the Tickler is actually suggesting that a corps of dandy dragoons, police on velocipedes, could control crowds without crushing people, and it adds by the same token that if the head of a dandy charger were shot off, the rider could simply “nail it back on again.” It’s another absurd image, but it pulls the velocipede into the frame of the techno-ethical debate about the policing of public space.

In 1819 the velocipede, cheap, lightweight, and fast, looked like becoming part of the technology of domestic crowd control, and post-Napoleonic expansion. As The Gentleman’s Magazine predicted, echoing Keats:

The velocipede is one of those machines may probably alter the whole system of society; because it is applicable to the movement of armies, and will allow further marches than have ever been undertaken.

As it turned out, the velocipede didn’t catch on, not for another forty years until pedals were finally invented. The point, though, is that the Romantics were quick to model their impact ethically, and on Britain’s fraught political landscapes.

Richard: No one, of course, reads The Tickler anymore, but maybe they should because the magazine’s whimsical take on fashionable new machines in 1819 actually hides an acute and sophisticated response to the Peterloo Massacre, and of course to all potential misuses of technology. It’s as radical in its own way as Percy Shelley’s better-known response to Peterloo, the poem “The Mask of Anarchy” was. It celebrates the energies of the crowd by seditiously summoning another crowd into existence.

Let a vast assembly be,

And with great solemnity

Declare with measured words that ye

Are, as God has made ye, free.

“The Mask of Anarchy,” Percy Bysshe Shelley

It’s not a piece of high abstraction. It’s a crowd-pleaser made up of slogans, and Shelley even managed to anticipate one of Occupy’s own slogans about the 99%, “Ye are many and they are few.” But let’s not forget this is rhetorical space, and how large public meetings in physical space were to be understood legally was crucial.

For the Manchester authorities, the Peterloo crowd represented a single, multi-headed monster. That partly explains why the mounted police were able to charge into the crowd and attack them indiscriminately. If you were there, you were guilty. It’s the same logic behind today’s kettling techniques, and we saw that last weekend here in Hamburg. Incidentally, the official position on the breaking up of the Rote Flora demo was that, quoting the official police spokesman, “The protestors suddenly started marching, and this was not what we agreed on with them, so we had to stop the march.” And the very same reason was given for breaking up the Peterloo meeting in 1819. As one government prosecutor explained at the trial of one of the organizers, Henry Hunt, “The crowd was provided with banners and advanced with a firm military step, presenting every appearance of troops upon their march.”

Ever since the French Revolution, that fear of marching crowds has never really gone away. It’s always there beneath the surface. Romantic literature was fascinated by the idea of crowds as potentially government-toppling monsters, including the most famous Romantic novel of all, one of the most famous novels, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Frankenstein was published in 1817, and that’s two years before Peterloo, but these were already riotous times, regularly punctuated by enormous gatherings of sixty to eighty-thousand people protesting against the high price of bread, loss of jobs to machines, and corrupt politicians.

As we all know, Victor Frankenstein is working at the limits, or beyond the limits, of Romantic techno-ethics. He creates a monstrous creature, and then when he sees what he’s done he immediately disowns it. The novel was straight away recognized in its own day as an allegory on techno-ethics, on the dangers of new scientific techniques such as galvanism, but it was also recognized as an allegory on the political relationship between a dissatisfied and underrepresented people and their uncaring rulers. The creature’s complaint that he’d been betrayed the father figure Frankenstein is also the complaint of the underpriveledged crowd protesting at their treatment by the state.

But it doesn’t end well for Frankenstein’s creature, right? And the first thing that radical lawyers after Peterloo did (and these were not secret trials, as Chelsea Manning’s was, but these were public show trials) was to build their clients’ defense cases around an agent-based rather than a flow model of crowd dynamics. As one Romantic attorney insisted, a person’s presence in a riot did not in itself prove riotous behavior. Quoting from the trial records,

The third and last charge was seditious riot. What was riot? There was no such thing as riot in the abstract; the individual must be found actually rioting. Even if a multitude was riotous, a man could not be made a rioter, even if present, if he was found holding no participation in the tumult that prevailed.

The Trial of Henry Hunt (1820)

Anne: Such arguments won the day, as can be seen in the current UK police manual of guidance on public order policing. This is the theory, anyway. Reading from the manual,

As with any crowd, the protest crowd is not a homogeneous mass but a collection of groups and individuals who, while sharing the same voluntary participation within the crowd, may with to express themselves in different ways.

Police Manual of Guidance, Public Order Policing (2010), Section 5.51

So how one understood interaction within crowds in the Romantic period was crucial. It could mean the difference between freedom and the scaffold. The questions Romantics asked themselves about crowds are the same as computer vision asks itself now, questions about how crowds form or how information was transmitted across them, whether behavior could actually be predicted, and whether crowds were collective entities or made up of individuals.

The agent-based modeling technique such as the social force model appear to have settled some of these. They’ve transformed sub-domains of surveillance such as event detection and group tracking, and it turns out one of the keys to accurately predicting and interpreting human interaction within high-density environments is velocity.

![Riccardo Mazzon, Fabio Poiesi, Andrea Cavallaro, "Detection and tracking of groups in crowd" [PDF]](http://opentranscripts.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Policing-the-Romantic-Crowd-10.png)

Riccardo Mazzon, Fabio Poiesi, Andrea Cavallaro, “Detection and tracking of groups in crowd” [PDF]

If you look at these pictures D–F here, the deceleration subject (with the shortening blue arrow) produces attractive force as he approaches a stationary group. Deceleration indicates affiliation, or in Romantic terms, sympathy. Because as Mary Fairclough has shown, Romantic activists regard the movement of information across crowds as an instinctive flow of sympathy.

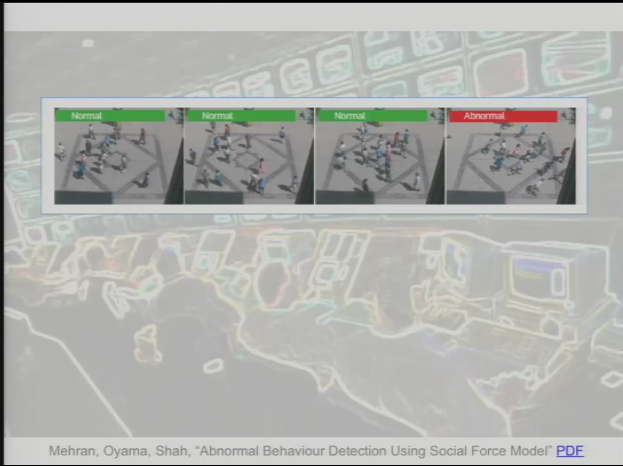

The authorities on the other hand, saw this propagation of data as contagion. Modern visual analysis uses the phrase “attractive force” to describe the relationship between people, which sounds neutral. However those Romantic terms, sympathy or contagion depending upon your political outlook, are still there beneath the surface. As you slow down you give up social information, purpose, which the algorithm then parses either as normal or abnormal. But of course such terms are ideologically freighted.

Mehran, Oyama, Shah, “Abnormal Crowd Behavior Detection using Social Force Model”

For example, does the data set here from left to right show escape, panic, or could it depict the beginnings of a flash mob? And how much interaction in crowds is normal, anyway? Clearly spatial context is crucial, but even here the researchers’ assumptions aren’t neutral.

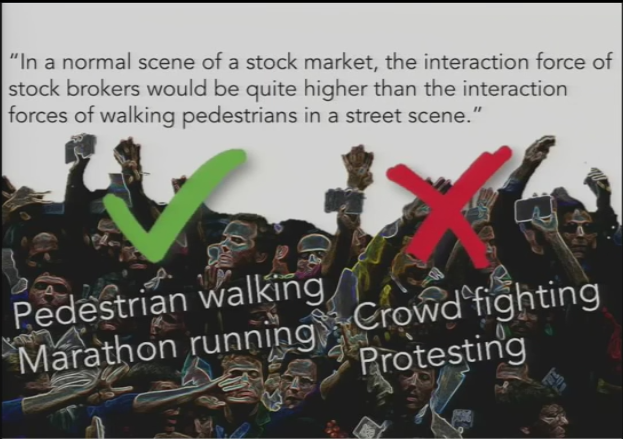

In a normal scene of a stock market, the interaction force of stock brokers would be quite higher than the interaction forces of walking pedestrians in a street scene.

Mehran, Oyama, Shah, “Abnormal Crowd Behavior Detection using Social Force Model”

For most people there’s nothing normal about the scene of a stock market, but what’s more, the binary grouping of normal and abnormal in these much-used datasets (they’re from Getty Images) is very revealing.

In the category “normal crowd scenes” we find pedestrian walking (Is there any other kind, I wonder?) and marathon running. And under “abnormal” we find crowd fighting and protestors clashing, but public protest isn’t abnormal. It’s of course part of the democratic process. Today’s SFM multi-object tracking techniques don’t only predict where objects and groups moving through crowds are going to be, but they also predict where people have been, and this is potentially really scary. Quoting the paper,

[Trajectory estimation] explains the whole past, as if it has always existed. We can follow a trajectory back in time to determine where a pedestrian came from when he first stepped into view.

Leibe, Schindler, Cornelis, Van Gool, “Coupled object detection and tracking from static cameras and moving vehicles” [PDF]

In this brave new statistically-plausible world it’s possible to exist in two pasts simultaneously. One question immediately arises, then. To what extent will surveilled subjects in the future be held accountable for their estimated past movements?

Richard: It turns out that the Romantics worried about precisely this question. So to finish, we want to show you a Romantic data set of crowd interaction, and one that powerfully explores the psychological impact of projecting somebody backwards into an estimated trajectory. It’s a good example of how Romantic literature and art opens a space of shared imagination that’s still available to us now.

London, 13th of September 1819. Four weeks after Peterloo, two weeks after that Tickler article, and one o’clock in the afternoon. Two political processions were are about to take place. The first is enormous. It’s up to 300,000 people, possibly the largest Romantic crowd ever, and they’ve gathered to cheer the activist Henry Hunt on his way back into London to stand trial for treason for his part in organizing Peterloo. His supporters are calling it “Hunt’s Triumphant Entry into London.” The second crowd is also enormous, and it’s filled with dark shadows and suspicions. That crowd is accompanying Christ into Jerusalem. And for one man that day, our poet John Keats, both processions are taking place at the same time.

So it’s the largest gathering in London ever at that date. Odd then that Keats hardly mentions it in his letter.

You will hear by the papers of the proceedings at Manchester, and Hunt’s triumphant entry into London. I will merely mention that it is calculated 30,000 [he means 300,000] people were in the streets waiting for him.

As I passed Colnaghi’s window I saw a profile portrait of Sandt, the destroyer of Ketzebue. His very look must interest every on in his favour.

John Keats, Letter of 18 Sept 1819

It’s odd he says nothing about the banner or the flags, and actually he’s more interested in this portrait of Sandt. The year before in 1818, Karl Sandt had stabbed the distinguished dramatist Kotzebue after accusing him of betraying the nation. So two crowds, one real, one a painting.

In that painting, “Christ’s Triumphant Entry into Jerusalem” we find Keats’ face, painted by his one-time friend Benjamin Robert Haydon. The painting hasn’t been exhibited at the time Hunt’s procession takes place, but Keats is very familiar with the painting. He’s seen it propped up in Haydon’s dining room, where it’s been the backdrop to many radical dinners, absorbing some of those radical energies and perhaps some of the atmosphere of suspicion. By August 1819, Haydon’s relationship with Keats has disintegrated. For the painter, Keats is an opportunist who’s only using the activist networks as a way to get his work out in the radical press.

Benjamin Haydon, Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem

Perhaps you’ve already noticed that Keats is the only person speaking in the crowd. There he is alongside other famous faces, Voltaire, Newton, Wordsworth, Keats is in green. He’s the only one talking because he’s found himself cast by Haydon, who’s fallen out with him by now, in the role of the infiltrator, the whisperer, the betrayer, the agent provocateur. In short, within the allegory of the painting, as Judas himself.

So as Keats stands around the London crowds, looking at Hunt’s supporters and seeing Christ’s, he must have felt uncomfortable. Haydon’s painting itself becomes a parable of the reform movement closing in on itself, of political friendships straining under the pressures of surveillance, and of what happens when social confidence breaks down. So when Keats tells us in the letter that he doesn’t feel part of the crowds it’s because he’s standing in two crowds at once, like many of us today. He’s a quantum Keats, a Keats who disturbs our sense of historical narrative. A double exposure. A double agent. That face in the print shop window of Sandt and his victim Kotzebue must’ve brought home to Keats, and mediated, the still-fraught dyadic identities of friend and betrayer, activist and spy. Finally, in many ways, that painting of Haydon’s is one of Romanticism’s most profound and moving reflections on the personal and inter-personal damage caused by surveillance culture.

We’ll leave it there. Thanks for listening.

Audience 1: My knowledge of the Romantic movement is not really extensive, but I do associate it also with a fear of technology, and not necessarily with crowds but with individuality, and I wonder if you could elaborate a little bit about the notion of Frankenstein which is often read as a sort of call to engage responsibly with technology, and also of a broader sense of Romantic distrust of crowds, where it’s precisely the big groups of people in which you lose your individuality, and as a result you get these traditional Romantic heroes alone in nature without an iPod.

Richard: It’s a fantastic question, and you’re absolutely right. In a sense, until recently the orthodox view of Romanticism is that it is a period of the emergence of the individual genius, the great romantic solitary genius who he (usually a man) is really just a conduit or hollow bone for inspiration to travel down onto the page, and the Romantic hero emerges with a fragment, all he can grasp from the great infinite.

I say that’s the orthodox. That’s being challenged and we now have a much more nuanced sense of Romanticism as a period of coterie, of circles of writers gathering together. So the idea that Keats, for example, is a poet of autumn who sort of floats over the earth having cut himself free, a transcendental figure who writes about the great eternal themes of beauty and truth and music. In actual fact he’s friends with a man, Leigh Hunt, who’s served two years in prison for insulting the Prince Regent. He called him “a fat Adonis of 50.” Fortunately he survived prison, but that’s what the state did to him.

Keats wrote a sonnet celebrating his release from prison. The first thing he did was try to get an introduction and part of the agon between Haydon and Keats is that Haydon was really the conduit into this radical circle of poets. Keats very quickly left Haydon to one side, and sided with Leigh Hunt because Leigh Hunt had a newspaper and published Keats.

So it is a period of coteries, but the whole thing about the crowd, it’s also a time when the crowd is gathering to itself a sort of sense of group agency. After all it was the crowd that wreaks havoc through France. It’s what the British authorities are frightened of. And that’s why as soon as they have hints the Peterloo crowd is drilling as a military force, they are very scared and they send in the police and they disperse them. But it’s a great question.

Audience 2: A little bit of an anecdote first. The murder of Kotzebue was followed by the Karlsbader Beschlüsse in Germany, and it really really oppressed the civilization and was followed by the Biedermeier thing and so on, but what I wanted to ask is was there in Great Britain anything similar to that? Was there any oppression by the politics, especially after the massacre?

Richard: Yes, is the answer to that. The Six Acts immediately follows Peterloo, and the Six Acts essentially criminalizes people gathering in assemblies. It’s already a period where Habeas Corpus is it’s [? German phrase] as you would say. It’s been lifted in the 1790s, it’s lifted again in 1870. It’s a very repressive period. It’s a period of wide infiltration of coteries and crowds by spies, infiltrators. A lot of Romantic literature meditates on this, often in oblique ways because to say it openly was dangerous. You ended up in prison like Leigh Hunt.

So it is an oppressive period and the first thing the state does is a series of repressive legal measures aimed at preventing anything like Peterloo happening again. Not the violence, but the crowd activism.

Audience 3: My question, it’s more like asking to elaborate on the part about the soft policing. Because I don’t think there’s much more being talked about that here, and I think it’s really good to bring that up because I think that’s a really really dangerous current that has been going on for a long time, as you’ve said. But developments now are like, just questions about what we can do to avoid this kind of analysis, and where there’s more information on this.

Richard: You [Anne] have strong views about CCTV in Britain, for example.

Anne: Well, Britain is the country with the most CCTV cameras and private CCTV cameras in the world per head, really. And the drones we’re just twenty kilometers up from, are basically just trying to find out new techniques where they can go into crowds, follow individuals, follow groups of crowds. They have this visual analysis technique where they’re able to parse one group inter-merging with others, and then dispersing again, and especially in crowd systems or situations like demonstrations, protests. It’ll be very useful for the police, and it’s all been tested just below where we are.

Richard: The first police drones that were used to monitor crowds were actually in Liverpool. And the first velocipede often went into duck ponds (according to that cartoon), but the first police drone for that ended up in the river Mersey.

But in terms of what you can do about it, it cracks us up because there’s the argument well, as soon as you stop talking about killer robots people will say, “Well yes, but drones do very useful things.” And they do. Aberystwyth University, where we’re from, drones are used to measure nitrogen levels in fields, to count sheep, a transferable skill set there. Lots of things. But it doesn’t mean we have that we have to have killer robots. And the debate is getting going in Britain.

CCTV I think we’ve become accultured into, it’s normalized for us. People don’t see them.

Anne: And they actually advocate for them.

Richard: People want them. So streets will say, “Why haven’t we got a CCTV camera protecting that wall at the end of our street?” The Council’s very happy to provide them, usually.

Audience 4: It seems like a lot of this [inaudible] ahead is getting people to believe that this is good for them, and reinforcing that, encouraging them to believe that.

Richard: They’re there for our safety. You’ll always find those on shields.

Anne: But then again, we’re both educators working in different institutions. And I think our role is being multipliers and also educating anybody that comes across exactly with giving them opposite views.

Richard: I teach them in the university. It’s too late, but Anne sees them in the further education college where their brains are still a little bit more malleable, [crosstalk] so it’s tough to do that.

Anne: So you think.

Audience 5: How much of the problem with policing and over-policing in the Romantic period was due to the fact that the state simply didn’t have the right toolbox? I mean, it’s important to remember that the people who were sabreing down innocent women and children in Peterloo, they weren’t police, they were the Army. Chelsea barracks existed to police London because there wasn’t a police force.

Richard: It’s an important distinction that they weren’t police, they were the [ownery?]. It was the paramilitary force, a militia, really. And they’re poised awkwardly between a regular police force and the army, true. So it’s paramilitary. But they were used as a police force in different places

Audience 5: The other thing I’d find quite interesting is that you’re sort of focusing on urban policing. How much does this work with more rural policing? What comes to mind instantly with Wales is the Rebecca Riots against tollbooths, toll bridges, and toll roads.

Richard: We have a proud tradition in Wales, stretching back to the Rebecca Riots and beyond, and actually Chelsea Manning could be seen as part of that radical tradition. She had her teenage years in Britain and there’s been a play recently (I think the only major play so far) Tim Price’s “The Radicalization of Bradley Manning.” It was first put on by the National Theatre.

In terms of wider policing issues, in actual fact the first thing The Gentleman’s Magazine said about the velocipedes was this is great, we can pursue thieves out of the capital into the countryside now. So they were very adaptable in the way they saw the potential uses of this technology.

I think I lost your question slightly there, but…

Audience 6: I wanted to say thanks for your talk first. It was really really great, and also I guess I’ve got a point and then a question, if that’s alright. The point is more of an elaboration on crowd-control policing in the UK today. I think I’m not the only person who was at that protest that you—

Richard: Was it you who cheered?

Audience 6: Yeah! I find it really really interesting that you brought up the lawyer’s defenses and the idea of just being at a protest, or in a protest crowd, being not enough for conviction, because now that’s basically the definition of the charge of violent disorder, which is the catch-all charge used to prosecute protestors and people on the streets in the UK right now. But your distinction between being in a crowd and being individuated as part of that crowd is really important I think for understanding how crowd-control policing works right now, because you can be prosecuted just for being part of that crowd. But at the same time people are being prosecuted because they’ve appeared on spotter’s sites, on police cameras. And from the student riots in 2010, you saw people being picked out of the crowd, people’s faces being put up in the newspapers, released by the police. They had twelve pictures shaming mostly young people of color. And the idea that you could be individuated and picked out but at the same time prosecuted for being part of a larger movement as a tactic of intimidation, and I guess that was my point.

My question was if you had any more information about what was the reaction to radical art in the Romantic period in terms of a political backlash? What was the state’s reaction to Shelley and Keats writing all this stuff, because I don’t know enough about that.

Richard: It’s a technical process of de-individuation, that’s what a lot of this technology is supposed to do. We de-individuate all the time just by slowing down as we approach a group of people, so it’s an excellent point.

Anne: The first point I think for today, before you say your part about the Romantics, is there seems to be a difference between the theory as we’ve seen in the police manuals, and what they do on the streets. There is this lecturer in Leeds who has very successfully worked with the police in football crowd situations, where he taught the police (and that’s where this manual comes from) how to not see a crowd as a mob, as an entity, but see the individuals. And it’s worked very successfully, de-escalation techniques and all the rest of it, but it seems like for political protests nothing of this has been taken into account. So the theory and the reality is very disparate there.

Richard: Absolutely. That’s Clifford Stott, he’s doing that research and it’s valuable. I think it’s a really important distinction, stadium crowd and social panic of that kind, and protest are seen as very different things.

As for the Romantic response to radical art, very little in many cases because the politics was sublimated or sort of displaced onto nature poetry often. So what looked like a nature poem, pastoral poem, we talked a bit about this last year, is often in a sort of steganographic way radical literature that is disguising itself. And that’s why it remains such a rich resource because we can pick over these things now, and we see those radical agendas and discourses that at the time were purposefully disguised. So the Romantics, in a sense, we can talk about unfinished conversations and continuities.

Presider: We have one last question from the Internet.

Audience 7 (CCC angel): We spoke a lot about history and the present, but there’s also the future, and the question is do you expect any pre-crime laws in the near future? We already saw those pictures where people could be surveilled in a way. What can they do with it?

Richard: So Minority Report, predictive policing of that kind.

Anne: Well, they’re doing that already, aren’t they?

Richard: Yeah, it’s very successful. It would be disingenuous to suggest that we had all the answers, and certainly Romantic literature and art is a rich resource, but I’m not quite sure how far into the future we can project. And we’ve seen the dangers of doing that, those estimated trajectories. I don’t know. I think our sense is that autonomous and soft policing is raising all sorts of ethical issues, and quite where it’s going to go is anybody’s guess. But I would guess that it’s going in that direction.