Jamila Raqib: So that was me that found that correspondence between Gene Sharp and Albert Einstein. And at the time that I found the letters, I had already worked with Gene Sharp for more than ten years. So of course I knew about their existence and the story behind them. I was always so impressed and found it so incredibly moving that the person that I worked with, that I learned from, who I respected so much, had been told by the great Albert Einstein—this sort of mythical figure—that he admired him. It was an incredible example to live up to both professionally and personally.

So when Gene decided to defy the draft law, he was comfortable and secure with his decision. He had that resoluteness that comes from knowing you’re doing the right thing, even if there’s a price to pay for it. But still, a lot of people must have told him that he was making a mistake and that he was foolish for throwing away his future. So I can only imagine what a massive moral boost it must have been for him to receive a letter back from Einstein saying that he, one of the most famous and respected people alive, supported his act of defiance.

For years I asked Gene about the letters. We were all very curious about them. His answers were always sort of dismissive. He said that he had lost track of all the papers from that time period. He hadn’t actually seen them since the 1950s, so when I heard that I gave up. I assumed the letters were lost to history. So you can only imagine what an incredible moment it was for me to open that box, to see the folder titled “Albert Einstein” and to know exactly what was inside. I’m so excited that the letters are here with us today at the Lab. And I’m hugely grateful to Gene and to the board of directors of the Einstein Institution for lending them to us to display for the first time at such a fitting occasion.

Einstein risked his reputation in order to stand up for his political beliefs. When he was asked how is it that humanity had progressed so far as to discover atomic power but not the means to keep it from destroying us, he said the answer was simple. “Politics,” he said, “is more difficult than physics.”

He saw how the political climate in the United States was becoming increasingly hostile to scientists and intellectuals and teachers. He was worried about the attacks on the press, the rise of authoritarianism, the degradation of human rights and civil liberties, the scapegoating of people who were different whether because of their religion or their beliefs. Dangers that are very much echoed in our political culture in society today.

Gene has gone on to become a well-respected and well-known scholar. The so-called Machiavelli of nonviolent resistance, and the Clausewitz of nonviolent revolution. He’s written dozens of books that are read by people on every continent, and he’s influenced social and political movements around the world. But I like to think that his work had its roots in that early encouragement from Albert Einstein. So much so that Gene ended up naming the institution he founded after the person who had been so supportive at such an important moment in his life. And who told him that his thinking was valid and that it was “worthy of attention and propagation.” It’s like your intellectual idol telling you your research is on the right track.

That thinking would go on to be the basis of Gene Sharp’s intellectual work. That strategically-applied nonviolent defiance offers humanity the best hope for bringing about a world with more peace and justice. Most of us here, at least those of us who grew up in the United States, were raised with inspiring story of Rosa Parks’ defiant act when she refused to go to the back of the bus. The story we’re told is that Rosa Parks was a quiet seamstress. That she was a good Christian. She got on the bus, she was asked to move, she refused and was arrested. We’re told that it was a one-day thing for her and also that she was the first to be arrested on a bus for resisting segregation.

But Rosa Parks’ activism started long before her defiant act. What’s left out of the story is that she was politically active for two decades before that. She was a secretary of the local NAACP chapter. And she’d been removed from buses before. She was a smart lady and a tough one, and she knew what she faced with her act of civil disobedience. She was making a calculated decision that day. Later, when she was asked why she did what she did, she said people always said she refused to move because she was tired. But she said she wasn’t just tired, she was tired of giving in.

When she committed her act of civil disobedience, the black leaders of Montgomery seized the moment. They realized that Rosa Parks’ arrest was a perfect opportunity to test the bus segregation laws in federal court. At the same time, a bus boycott was organized. Which was only sustained because Montgomery’s black community established an elaborate car pool system. Which itself was only possible because of the strength, the networks of activists and organizers, and the institutions that had already been organizing around the issue. And the bus boycott brought to prominence a charismatic but previously unknown preacher named Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

The power of Rosa Parks’ act came from the fact that it was part of a bigger struggle for civil rights for the black community. A struggle that didn’t start or end with her. She committed her act on the back of a long history of activism and organizing and institution-building, both by her and the black community of Montgomery and beyond.

This behind-the-scenes planning is often overlooked by observers and by the media because it’s what the cameras often can’t capture. I’ve witnessed it for fifteen years at the Albert Einstein Institution. This quiet capacity-building and structural work. The planning and preparations that make movements more effective. Like the Chinese human rights attorney who is serving five years in prison for distributing copies of books about civil disobedience. Or the Vietnamese garment worker who secretly hands out tapes of recordings outlining worker’s rights. Or the Zimbabwean activist who told me that she works two jobs—she’s raising a family—but at night after her children go to sleep, she translates material about how to organize anti-corruption campaigns in her city.

Nonviolent defiance has a long and rich history. One of the earliest documented cases is the plebeian withdrawal of Rome in 494 BC. It’s probably the first documented case of a general strike. Since then there have been more than 1,000 cases, across cultures and religions, when people have chosen to fight not with violence but with social, political, and economic forms of non-cooperation and defiance. Their objectives have been diverse. To fight invasions and occupations, to undermine dictatorships, to defeat coups, to defend the rights of women, of workers, of minorities, people of different sexual orientations. And to protect the climate.

So when people conduct struggles effectively for social and political objectives, how do they actually do that? This was Gene’s essential question. Gene studied these cases in order to see what we can learn from them. The more he studied nonviolent action, the more that he learned about what made it work. What allowed it to succeed and fail in other cases.

From this knowledge Gene Sharp created a system out of what people had been learning and applying by trial and error. He found out that most often when people chose to use non-violent struggle over violence, they didn’t do so because of a principal belief system or because of their religion, but because it was more effective. They understood that it offered them certain advantages. That when you choose to fight with violence, you’re choosing to fight with your opponent’s best weapons. Gene learned that the way to create lasting change is to undermine oppressive systems so that they crumble. But that equally important for a movement, to build their capacity and become strong. That just as a weak person is more vulnerable to abuse, so also is a weak society more vulnerable to abuse and tyranny.

At the root of this system is an understanding of power. The idea that each of us, whether we live in a dictatorship or a democracy or something in between, we hold enormous power through our actions. What we do or what we refuse to do. It’s the political application of a type of human behavior that luckily comes very naturally to all of us.

And that’s basic human stubbornness. It’s the capacity and the willingness to defy, to disrupt, and to refuse to cooperate even when that refusal carries enormous costs. And when that is done as part of a plan in accordance with a strategy, together with people in your society and allies outside of it, it becomes a powerful tool.

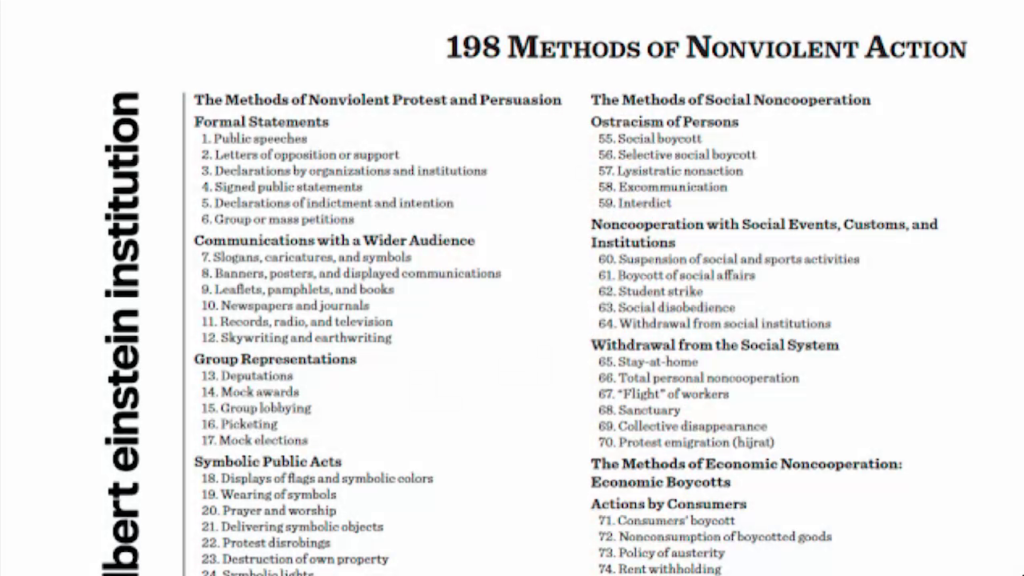

198 Methods of Nonviolent Action, Albert Einstein Institution

This is Gene’s list of 198 methods of nonviolent action. These are the specific actions that people can carry out, ranging from protests, symbolic strikes, economic boycotts, labor strikes, political non-cooperation and social non-cooperation. And finally, nonviolent intervention, which is the most powerful category of methods available in the nonviolent arsenal.

Here in the US we’re witnessing a resurgence of political engagement. People realize that they have a role in defending the institutions and democratic values that they see as under threat. Albert Einstein said that our rights are only secure if every citizen recognizes their duty to do their share. And that the intellectual has even more responsibility. Because of their training, they’re capable of more influence over public opinion.

Einstein got it right. Because democracy is not something once achieved in a society means we then get to sit back and relax. For democracy to work, for our institutions to function, requires our constant vigilance and participation. It’s so important today that as we watch these powerful examples of defiance that are happening in our country, the Women’s March; the March for Science; disruption of town hall meetings; protests against the immigration ban; establishment of sanctuary cities; and on and on, we must now figure out how to absorb this momentum.

One of the most hopeful trends that I’ve observed in recent months is how people are organizing in new ways. Which means that they’re not just protesting policies that they don’t agree with, they’re actually building the power capacity needed to actually win. They understand that weak and fragmented people can’t be expected to act effectively on social and political issues. So they’re working to create networks of people. Small groups of ten, twenty people who meet periodically in living rooms and classrooms and places of worship across America. They talk about the issues that they care about. They organize educational workshops. They discuss their strengths and weaknesses. The resources they have and the resources they can get in order to meet the needs of their communities. In short they’re learning to think strategically.

And it’s not just groups in the United States but activists and organizers from all over the world, who tell me that they understand they can no longer reinvent the wheel and operate based on intuition. This is especially true because they’re increasingly facing opponents who have massive resources at their disposal, including control of the media and the banks and the transportation system, as well as the tools of violent repression. The police, the military, and the prisons. And these opponents are constantly learning and constantly developing better techniques to defeat social and political movements. Which means that movements must also innovate if they’re to have a chance of winning this nonviolent arms race.

The challenges to conducting successful struggles for change are many and can seem overwhelming. But the good news is that developing capacities and strategies that have a chance of working are within our capacity. The tools to do it skillfully exist and they’re being improved and refined by people around the world every day, many of whom are in this room today. This type of knowledge and understanding will make the struggles of the future more effective than those of the past. It’s up to us to contribute to that so that the future is one of less violence and oppression.

Today it’s an honor to be here and to share the stage with such a thoughtful, talented, and brave people. And to the winners of this year’s Disobedience Prize, let me be the first to congratulate you on the actions that you’ve taken on behalf of us all. And to the Media Lab and everyone else who has made this day possible, thank you so much. And to all of you, thank you all. So I hope our day together provokes your own thinking about what your next act of thoughtful disobedience will be. Thank you very much.