Photo: Tom Kelly

Eleanor Saitta: Today we want to talk to you about the role of technology and society in the longer arc of human history. We’d like you all to take a couple things away from this talk. The interaction between a piece of technology and society is rarely settled in two or three years, or ten years. We’re still as a society just barely learning how to use email. If you think, even in the past five or ten years, the way email’s used in professional contexts has changed radically. We don’t really know what it means yet. We think we have a reasonable understanding of how you use an auditorium. We’ve figured that one out. Mostly.

The other thing we’d like to talk about here and that we’d like you to take away from here is that while geek culture kind of grew up as an outsider culture, that changed. It’s at the heart of politics and the heart of social movements now because it’s the heart of how we communicate now. Geek culture and hacker culture used to be relatively apolitical, but now every action that you take and every piece of code that you write has political effects. You may may intend some of these effects, you may not intend most of these effects, but they’re there and we need to start thinking about and understanding these changes. And this is a change that’s happened in our lifetimes.

Quinn is mostly a kind of incoherent blend of anti-capitalist anarchism and California Libertarianism…

Quinn Norton: …and Ella is a Marxist Syndicalist, presumably with blood on her hands. But since she likes me a lot she’s promised me six minutes’ notice on the purge before it happens, so I can get a head start.

Despite the political parts of this talk, this talk is not about our politics, not about what Ella or I want you to do. It’s about what we’ve learned from examining the network effects that we live with now. Because fundamentally (many of you will recognize this) architecture has a politics and it has a culture. And while we were all kind of sitting around in our culture in Usenet in the 90s or wherever we got our start, being—like Ella said—outsiders, the world pivoted. It changed and surrounded us and put us at the heart of these matters. And so whatever you want to do politically, what we’re going to be talking about is the framework of the politics that technology is creating around the world right now.

Map: zonu.com

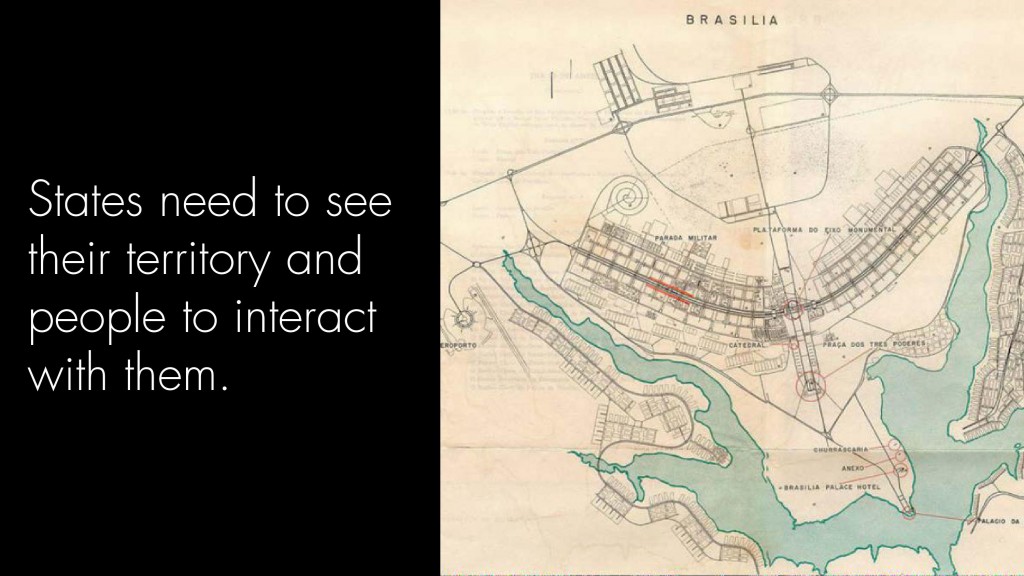

Eleanor: One of the really interesting structures in the world right now that we spend a lot of time dealing with are states. States have a couple of very basic things that they require to be able to interact with the world. They need to be able to see their territory, and the people who live in that territory, if they’re going to be able to interact with them. And this is simply a truth that applies to anything, to any time where someone needs to interact with a thing. If you can’t perceive a thing, you can’t interact with it.

This map here is the planned city of Brasília, which is a city that was built to be legible, to be understandable to the state. The notion that a state should, if nothing else, even if it can’t understand all of the rest of its territory, all of its other cities, it should be able to understand the city from which it governs. Of course, I don’t know how many of you are familiar with the actual city of Brasília, but it doesn’t look much like what’s indicated on that map. Reality has come back in and gotten a lot messier again.

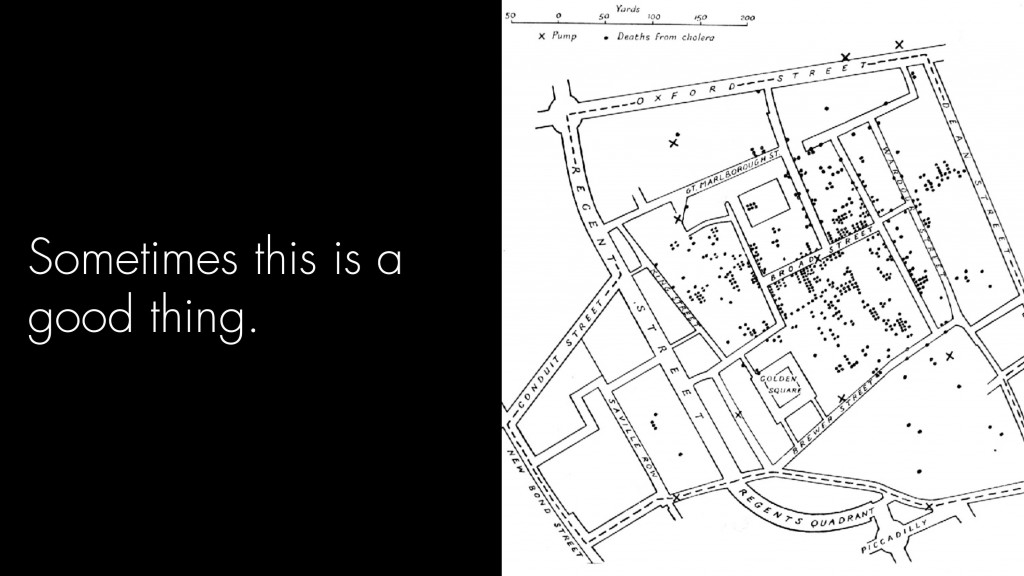

Image: Wikipedia

A lot of the time, the ability of a state to see its citizens and to see its terrain is actually a very very good thing. This is the Snow Map which founded modern epidemiology. It’s a map of cholera deaths in London around a particular well when they didn’t understand that cholera was spread through water. This map told us things about human disease transmission that have saved at least tens of millions of lives, and this is a form of surveillance.

Sometimes this is a bad thing. This is a map that the city of Amsterdam prepared from their very complete census records of where all the Jews were in Amsterdam, for the Nazis.

During the process of the societal adjustments following the revolution in France (and this was actually one of the demands leading up to the revolution from certain sectors of society) the revolutionary government as continued under Napoleon standardized on the metric system. One of the things that this did was that it eased a lot of the burdens on farmers who were having to deal with incompatible local unit systems being used to basically rip them off from what they should’ve earned on their profits. But it also laid the groundwork for tax standardization and for central control.

To paraphrase Chateaubriand, what he said at the time, “You know if someone’s using the metric system, that they’re a narc.” In other words you know that if someone is using the metric system they work for the government, they work for the order that is attempting to impose legibility on society.

In the state of Qin in the 4th century BC (no relation), the emperor decided that imposing surnames on the population was a good idea. They needed to be able to conscript people for labor and for the military, they needed to be able to tax people, and they need to be able to apply laws to families. Now, many of the ruling families (and this is true throughout the world in places where names have been put into force and have been imposed on people) already had surnames that were frequently attached to where they lived or where they ruled. But common people had all sorts of different ways of being known. And if you imagine you’ve got a dozen different ways that you can be named, and you might have some reasons to not want to be legible to the state, this is very very convenient for you. So assigning patronyms was a way of changing that power structure. And along the way it may have also changed some of the power structures in the family. It’s not clear, but one of the things that they attempted to do was to make the head of the family responsible for all the actions of the rest of the family, which you could reasonably see might have some cultural shifts.

This is really interesting because it shows that the vision of the state has consequences. When the state looks at the world, it makes things fall into the boxes that it’s measuring even if they didn’t before. In other words, networks weird legibility.

Quinn: This is I think kind of a controversial statement in this room right now, but I think that surveillance is actually a form human attention and human concern. And surveillance is what we do when we care about something, and sometimes that care takes positive forms, coming back to the cholera map. Sometimes it allows us to build infrastructure that works for a lot of people. Sometimes it allows us to prevent disease and feed children and so on and so forth. And sometimes it’s used for political control, but it’s always used in some way of concern. And like technology and many political qualities, it is neither good nor bad, nor is it neutral.

And I think that’s one of the things we have to bear in mind in this particular age of surveillance, that in many ways surveillance is the small touches that we do on each other. Surveillance is when we check up on each other and stuff like that. So finding a way to cast that where we can reclaim the positive and suppress the negative is I think much more the task than to fight all surveillance. It’s a much more subtle question than it would seem right now.

But when we talk about this kind of vision of the state, the state as watcher, the state as arbiter of money, for instance, the news cycle we have right now if we want to take it back all the way to 4th century BC China, this all makes more sense. It makes sense that nations are trying to get all the information they can because they’re trying, again, to make their world legibility. And when they get all that information, they’re putting it into the categories that they perceive are meaningful. And that means destroying by ignoring the ones that aren’t. I think one of the things that’s really useful about reading this history is it gives you a measure of prediction on what states are going to want to do with technology. They want to keep tabs on their people, for good and bad reasons, and there’s always both good and bad reasons. They want to take the power that they get by being the state and use it to mold the country that they’re in.

That has been a tremendously progressive force in history, and a tremendously destructive one. But it still comes from the same fundamental impulse. And this is why it’s really easy for me to stand up and say a state will always spy on its people as much as it possibly can. Because states always have. Not just to maintain their power, but just to maintain the ability to control consequences, which is a point that we’ll return to later.

So we’re in an odd time of history, and I want to actually roll back to another moment in history and introduce you to William Tyndale from the 16th century. Tyndale had to flee one day from his native England, and he never set foot in England again. He died outside of England because he decided what he wanted to do was translate the Bible into English. Now, centuries before this, this was always a contentious issue, translating the Bible into the local language. It was generally in Latin. Centuries before this, Pope Innocent III had essentially sentenced to death people that would try to do something like this. The laity was never even to touch the Bible. It was to be interpreted and handed down from on high by the Church because the Church were the people who had the knowledge to understand it. It was a top-down picture. And Tyndale was part of a movement that wanted people to be able to take control of their own Christianity.

He was opposed by Sir Thomas More, now St. Thomas More, who believed that the Church was necessary to keep order. If this is sounding a bit Hobbesian that’s because it is a Hobbesian debate, and it is one that we’re still kind of—I’d say we’re in the third act of this. I used to think this was a good metaphor for where we are now, but actually I think this is just the same thing going on. So More and Tyndale got into a huge fight, and Tyndale was on the run, More was sitting with King Henry VIII, and they got into a big argument, and this argument spanned the continent at various points, about whether or not the Bible should be in English and people should be able to interpret their own religion.

Photo: ff137

And of course that got started because of this guy, Martin Luther, who created a bunch of Theses and stapled them to a door and then sent them all around the continent. Again, nothing on this list of church reforms that Luther and Tyndale and that whole crew wanted were new. Not a thing was new. What was new was that if you were Martin Luther and you wanted to say the Church needs to reform and you got on a horse to go tell people that that’s what you believed, the Church would burn you. But something had changed. And this is also how Tyndale and… The statement “Tyndale ran away and then they had a fight for years” doesn’t make any sense to most people in that era, and it just sounds assumed to us because of a communication technology and in this case that communication technology is the printing press.

Luther was able to put out his 95 Theses, sit safely with a patron in Germany and say the Church needed to reform. And the Church [was] occasionally like, “Could you send him for a meeting?” and he’s like, “No, I’ll stay here in Germany. It’s fine.” Originally, though, the printing press had been a huge tool of the Church. They were the biggest customers of printing. Not just to print Bibles but to also standardize the interpretation of the religion everywhere. They could print things out, send them out to all of Europe, and gain control and again, legibility on their religion. Make sure that everybody had the right materials, that there was no corruption in them, and spread them everywhere. That went on for a few years and then the dissidents got a hold of this technology, and it turned out they could do the same thing the Church could do. So the big question hanging over the 16th century was was the printing press going to reform the Catholic Church?

Well, in fact the printing press reformed everything on the planet and possibly a few things off the planet. They didn’t even have a language to ask the right question for the undertaking that they were embarking on.

Eleanor: Tyndale and More were two threads inside one institutional power, but there are a lot of kinds of power in society, not just one. The Church has waned in authority, Capitalism was in many ways just getting started. This was the birth of the East India Company. This was the birth of mercantilism in that same era. But the power of guns and power of money and the power of God are just three different kinds of power, and they all let you do different kinds of things. They’re commensurable with each other, they don’t act on each other, they don’t act on themselves.

If you have a pile of money, that doesn’t necessarily let you directly influence what someone else who has a pile of money wants to do. You can maybe take away their money or force them to do something else because you’ve bought the thing that they were trying to buy first, but there’s a lot of subtlety here in terms of how power acts, and this is one of the things that seems to be occasionally getting missed while we talk about, “Oh we need to force states to do such and such, we need to stop states from doing such and such.” There’s this, “Oh, corporate surveillance is the worst thing. Oh, state surveillance is the worst thing.” No, they’re different things, and they may be problematic in different ways. All power needs to be able to see the world in order to act. Whether you are a state or a corporation or a church, you need your own kind of legibility and your own kind of surveillance, whether that means figuring out if the people in all of the villages are showing up in church on Sundays and whether or not they’re doing any of these things that might be indicative of any of these various heresies that you keep hearing about. Well let’s go burn some people and find out. Or whether it just means that I need to be able to set cookies in your browser and figure out what kind of porn you like. That’s the same operation but for very different reasons.

Image: Pepper Spraying Cop Tumblr

States are panicking right now. They’re acting the way they are because they’re panicked. There’s a thing that Quinn calls the consequence fairy and it used to be that the consequence fairy was a very staid creature, and it would sort of float slowly around the room and alight on the shoulders of heads of state and popes and bishops and capitalists and say, “Your actions matter in the world. You’re an important person.”

And at some point in the last twenty or so years, the consequence fairy got drunk. And now the consequence fairy is kind of flitting around the room going, “You matter and you matter and you matter!” and everybody else is like, “What the fuck? How do we even deal with this because we don’t know how.” Because our legibility…you know, the world hasn’t changed, the stuff that we pull in is still the same thing but it doesn’t mean what it used to mean. We can’t interpret it anymore.

So one of the things we’re seeing right now is we’re seeing states desperately trying to hang on to not their ability to surveil but their ability to understand, but those don’t look different from the outside.

Rule of law was never intended to operate in a state of exception, and this is one of the things which is very interesting if we talk about rule of law as a response to unrestricted surveillance or to any other of the problems in the world right now. A state of exception and a state of rule of law are defined opposites. We now live in a state of permanent, but neither pervasive nor complete, exception, and this complicates all responses within systems.

Image: GQ

On a personal level things have gotten weird, too. Positional ethics is basically what happens when you join an institution, when you join an organization, when you join a network. That network, or that institution, has a set of ethics that are attached to it. And when you operate within that institution, you take on some of those ethics. You become the person that does the thing that the institution needs to do in the world.

This is not complete. This is definitely not total. Infrastructure does this too, and this is a really interesting thing for all of us who build communications infrastructure in the world. Infrastructure has an ethics. In a lot of cases right now, that ethics is actively suicidal. We are dealing with suicidal infrastructure that we’re embedded inside, and we cannot become non-suicidal ourselves entirely because we’re still tied into that infrastructure. We can only become in some ways sensible or human or humane again if we get outside of that infrastructure, but we can’t because that’s what runs society.

Things in our lives can sometimes override positional ethics, and this is where our friend Walter [White] really comes in, right? If you have kids, all of a sudden you realize, “Oh, I will do anything to feed these kids. It doesn’t matter what I thought my world used to be. My world is now different.” And one of the things that’s really interesting about life in a network society is that we don’t just have a single set of ethics, we don’t just have a single context anymore. We may find that we wake up in the morning and we go to work and we work on systems of state or corporate control all day and then we go home and we do other work to undermine the exact same systems of control that we were working to build all day, and we are literally fighting ourselves. That is one of the conditions of the next century.

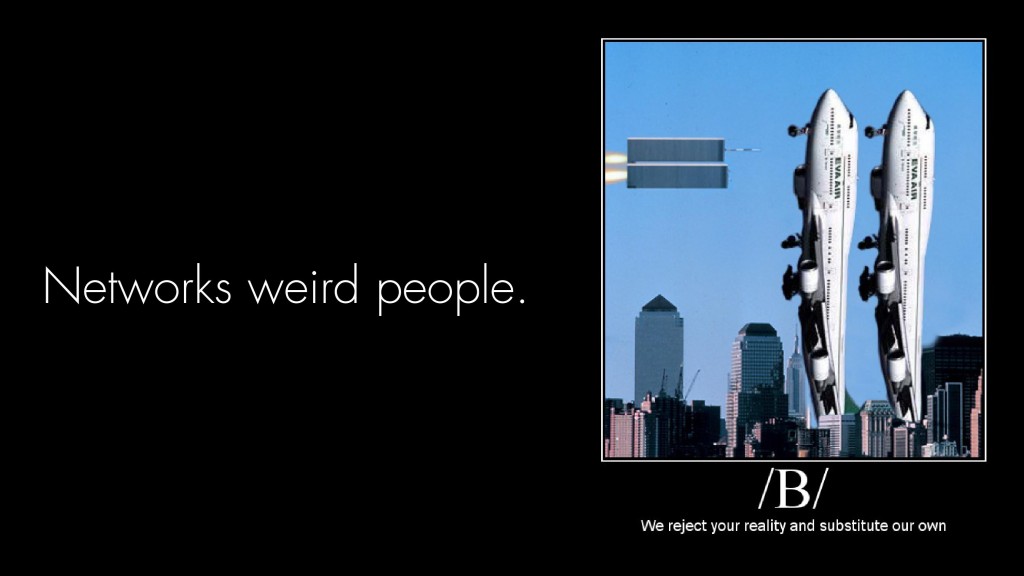

Quinn: One of the reasons that institutions are freaking out right now is because this network that we’re on makes people weird. And actually I like this particular “networks weird people” in almost the high medieval sense. They almost make people have a fey magic to them. And all of a sudden one person can become many people on the network. And that legibility, that several thousand years of getting a last name on you people, is suddenly gone because you’ve just invented fifteen new people, today. And ten thousand if you wrote a script to do it. And all of a sudden the thing that power has a grip on has weirded in that classic—it’s totally full of a fey and uncontrollable magic, and that’s what you are right now. That’s what you are becoming. That’s what people on the network have become.

And the network has its own logic, or possibly this, I’m not sure I want to apply that word here. But it’s really true that the network rejects your reality and substitutes their own. Those categories, those safe and understandable and predictable categories, those get weirded out, too. And we’re all kind of living through this process. This is all still within our lifetime. And we don’t have a social structure or even a language to describe the networks that we’re living in right now.

And it’s doing really really strange things to institutions. The Internet in particular turns conduits into barriers, and I do mean that the RIAA used to be the good guys. Their job from the 1950s was to standardize all the record players, to make sure that all the record players would play all the records, so that anyone could get music, and to set up distribution systems so that anyone around the country could get anyone else’s music. And this was actually a really interesting and magical thing they did, because if you were living in a Louisiana bayou in 1950, you didn’t hear music from New York until they fixed this system. And they’re one of the entities that allowed this common culture to grow up and these other options to enter people’s lives all over America.

And they didn’t actually really change what they did for the next fifty years. But the world did that pivot, the same one that put you at the heart of the matter, took this conduit of information and turned it into a barrier. And the people who are working these jobs, the people who lived through this whole cycle with the RIAA, I gotta say as a journalist who’s had to call them for interviews, it’s like calling crazy people. I have a lot of sympathy for them these days because they didn’t do anything wrong. The whole world just went cuckoo, from their perspective. And they’re grabbing at reality as best they can. In fact, so many of the things that would’ve been the awesome geeky things to do in the 50s and 60s have turned from conduits and generous ways of sharing information into the barriers trying to stop the network from doing their job better, because they’ve got those kids to feed. And they’ve got a mortgage, and damnit they were doing the right thing all their lives, why did it have to change now?

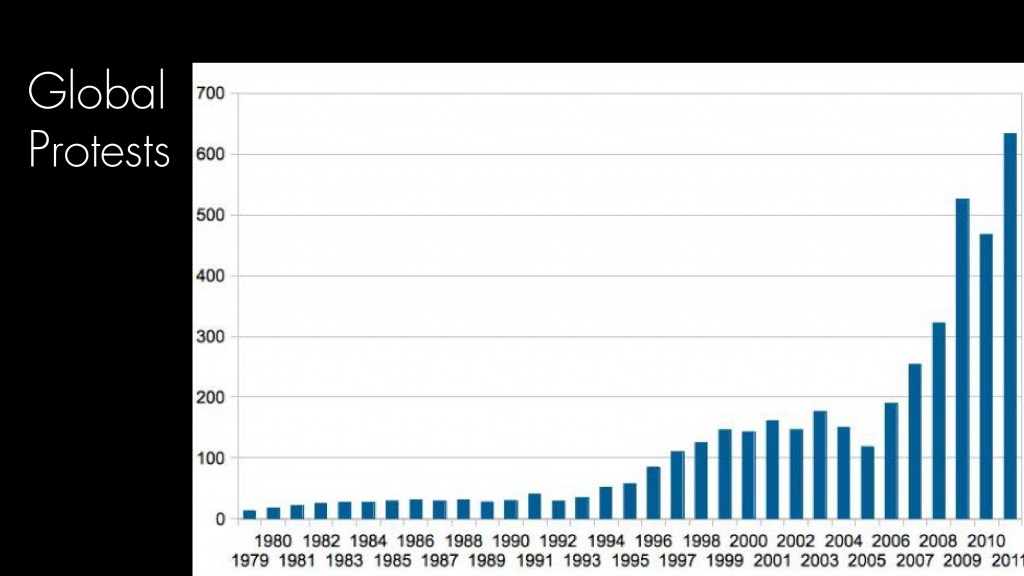

Chart: Predictive Heuristics

So what does it look like on a grand scale when these weirdings go on with institutions and people? Well, some of you have been familiar with this kind of graph. This is from 1979 to the present, level of global protests. And part of this I think we all know is fed by the fact that coordinating protests is now piss easy compared to what it was prior to this. It’s like signing up for a mass-tweeting and then going somewhere, and it’s something people can do in a few minutes. The people who set up the ACTA protest in Poland that brought down that legislation eventually weren’t people who had been working on it for years and building networks and doing trainings and so on and so forth. They were just like, “I’m gonna start a Facebook group.” And pretty soon there was 200,000 people in 300 cities crashing a treaty that was never even supposed to face any serious opposition. That came out of nowhere. That’s the one with the Polish parliament masked up. Talk about weirding identity and institutions right there.

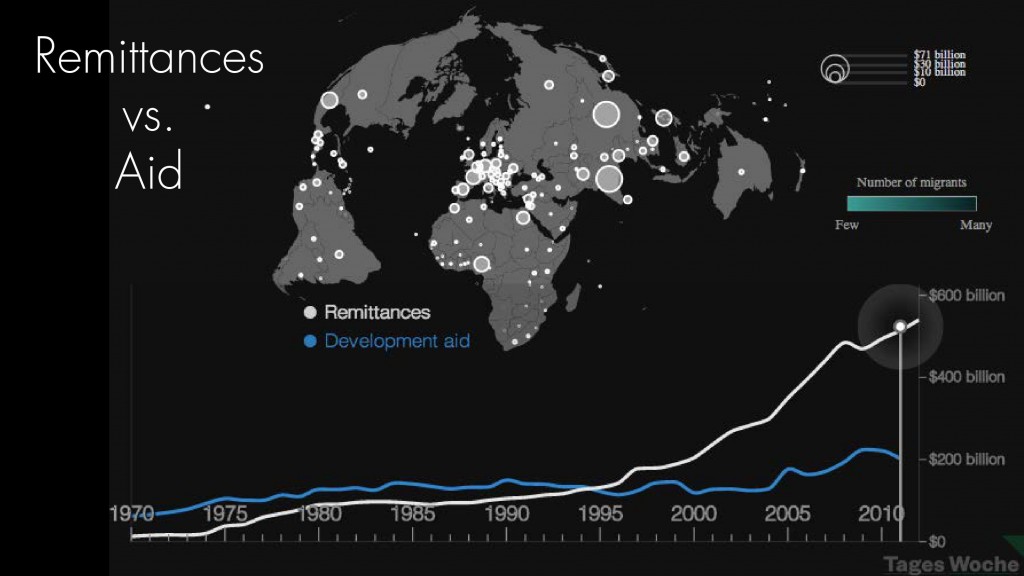

This one’s a little bit more subtle, but actually I think ultimately more important. Something that’s happened since the 90s, it certainly took off by the year 2000, and actually interestingly maps pretty well to that global protest graph (By pretty well I mean in a rough sense that it has risen on a similar plane.) which is that this bottom line is foreign aid from 1970 to the present. And that top line is international remittance. International remittance is the fancy-pants term for “sending money home to your family.” So what’s happened here is that nearly three times as much money is sent by immigrants back to their families as is sent to countries via foreign aid from governments, and possibly other fundraising institutions.

Why is that important? Because that’s a system of mutual care. It is again largely illegible or stepping out of the state. The number is probably higher than this because it is very very hard to count remittances that go through informal economies—a limitation that the people who studied this recognized—but by their very nature they are illegible, and they are often use for remittance by people who are trying to avoid taxes or avoid governments that are trying to skim off the top of the remittance economy. So again, the network is making things pretty weird.

Eleanor: I first got online in August of 1994, just before the Internet suddenly became a very different place for the first of probably the dozen or two dozen times that that’s happened since then. And that culture that I first came in on was a culture where we were kind of off in a corner doing our own thing. And that September, when all the college kids came online, and then everyone else started coming online, all of a sudden we don’t live somewhere off in a corner now. All of a sudden we live right in the middle of everything, and everything that we’re doing is going to keep echoing through history no matter what we want to do.

One of the things that means is that we need to learn history. It means we need to learn our own history. If we continue to ignore the shaping effect that we have on the world, we miss a lot of things. It means we’re going to keep repeating the same mistakes, it means we’re not going to understand the victories that we won in the past. It means we’re not going to understand the victories that other people won and see the similarities between the situations that we’re in now and that some French peasant was in 700 years ago, or some Chinese peasant was in 2000 years ago. That social change is really really critical. We keep hearing, “Oh, code is law, law is code.” There’s this equivalency now. I think there’s something deeper there as well. I think that code becomes, given 100 years, culture. And that’s a lot harder to predict, in some ways. We can look at a piece of law and make some guesses about what effect it’s going to have on the world. It’s a lot harder to make the same set of guesses about what a cultural object or a thing that will influence a cultural object is going to have on the world. But if we don’t start thinking about it we’re definitely not going to get there.

Quinn: One of the things that we’re talking about is trying to stretch out our minds, stretch out our conceptions of history, while living, while those institutions and those institutional ethics that we’re talking about push you towards thinking in quarters. Most of culture is currently conducted on quarters or maybe an annual cycle. But somebody pointed out to me recently that they can’t right now find any articles that are making predictions for 2014. Our time horizons have gotten so short that we are too scared to predict next month.

But we can look back, we can look back at different points and take lessons from them. Some of the things that we face right now are unprecedented, as all history has been, and some of it is patterns that we can learn from. And when we step back and look at not just things like Tyndale and More and the path they traced up to the Enlightenment, and again, interestingly, we can also look at things like the fall of the Roman Empire, the rise of paper money in China. All these things are things that can help inform us and make us understand the technologies that we face today. But of course there are limits, because every moment is unprecedented. And right now there are so many frickin’ people out there. That’s what’s so strange about this moment. Every second, 217 years of human experience pass on this planet. Since we’ve been talking, it’s something close to 500,000 years, in the course of this talk. That’s the human attention that has passed from seven billion people while we’ve been standing here.

And what I really want to start pushing on you, pushing you towards, is trying to look at that long time. Try to look at what the world was like a few hundred years ago, and try to imagine what you want the world to look like in a hundred years. Because that’s a question very few of us can answer at this point. Not what do you think it will look like. What do you want it to look like? What do you think is right for people in a hundred years? How do you hope people that you will never meet will live?

Image: Gigaom

People are different because of this network that we’ve built over the last thirty years, but they’re having to do it on brains that haven’t had a chance to change. Normally we have decades and even generations to adjust to these kinds of change. Currently we’re living through an age where we’re having to adjust to these changes in a biologically-challenging period of time. Billions of people, a number that none of us can conceive, not just the ones on the network but those touched by the network, touched by the presence of the network, are affected by what we as a community have built. Yes, we built a technology that lets governments monitor and control their people. We also built a technology that lets people escape the fates that their rulers and cultures had for them. And sometimes we built those things in the same applications.

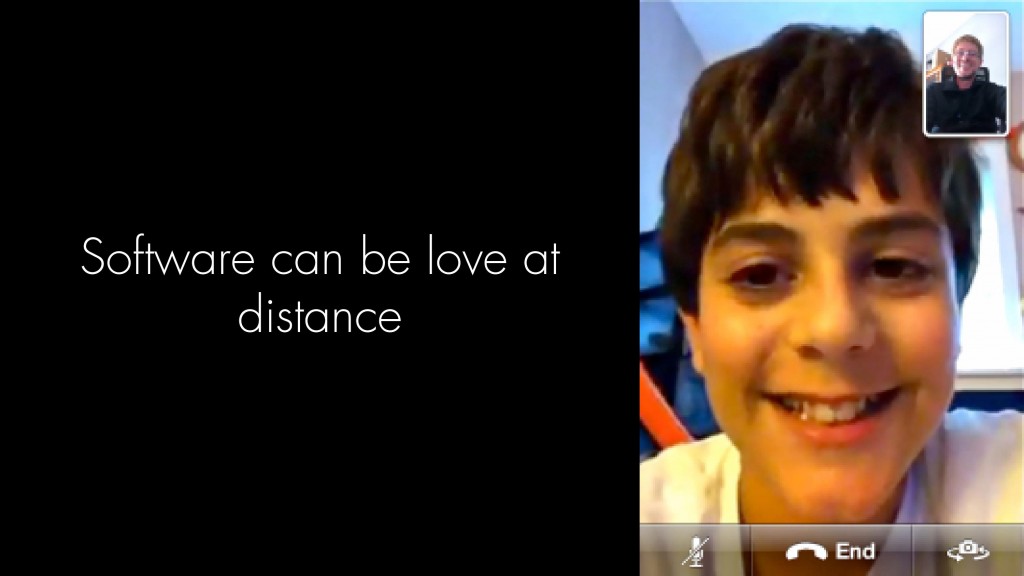

You have let millions, and perhaps hundreds of millions, of children know the mothers and fathers who had to leave them in order to feed them and care for them, a tradition that goes back many generations into social isolation and loss. You’ve taken away the power of economics and distance to make strangers of families. This is what’s buried in those dry remittance figures: People. Families. Families of origin, families that we create.

Distance no longer has the same power of our lives because of the things that we all built in the last thirty years. This is what mutual care looks like. It looks like the faces of people. It looks like their blood and their flesh. And this is what our technology affects, controls, and enables. You made millions of people care about millions of people they didn’t know existed. You made not just distance but the depth of time, the human record, all of a recorded history, you made it so present that we can pluck it out of the air at any moment. That’s what you did in the last thirty years. That’s what you gave close to two billion people on this planet in the last thirty years. That’s what you’re responsible for.

I know that you didn’t ask for this job. You didn’t ask for this role in society. None of you, not one of you, wants to think about the many people that can be affected by one fucking perfectly normal bug or mistake in the technology that you built. And this is one of the reasons we keep our heads down. No one became a geek because they wanted to be the center of political attention.

That just happened.

You don’t get to choose. You don’t get to choose what era of history you live in and what that era wants to do with you. And this is a moment when it’s all up for grabs. That’s what it means to say we’re on a burning planet. And what it means to say that we don’t have neutral ground is that you’re at the center of that fire. You set it. You’re one of the people that set it. You’re one of the people that tend it. And everything you do, the changes you make over the next months and years are going to chime down decades and centuries and shape the lives of people you will never know, but they will know you. For one thing, your lives are very well-recorded.

At this point, this is where we are in history, but we’re standing at a conference where we still have to remind people in the community to eat and bathe themselves. It is time for us to up our game.

Quinn: I believe we will be taking questions at the mics. And possibly from the Internet, I’m not sure.

By the way, many of the citations that we used, not all but many of the citations that we used in the talk are contained within these books and essays and so on and so forth, and together they make a pretty interesting follow-on curriculum, as it were, for the concepts we’ve been talking about.

Audience 1: Thank you for the presentation. After the printing technology came, we saw emancipation of the human being, human rights, end of slavery. Do you think there could be something similar happening with new man, which is enhanced man, and also going through emancipation and of digital slavery and new human rights?

Quinn: Interestingly, we saw slavery as an explicit condition abolished but we saw it as an implicit condition expanded. So we have various people who end up essentially living in slave-like conditions. They can’t be bought or sold (well, in some cases they almost can be) but it’s interesting to watch how that institution changed and I think actually it’s a really really important point. Because this kind of modified human being (we’re all basically cyborgs of some sort or another at this point) living on a cyborg planet. If you look at this planet, this is not what the planet naturally looks like; this is what we have now. And I think that the job of our generation especially, and the next generation, is going to be to try and end the slavery without instantiating a new, subtler form of slavery like we did last time.

So this is coming. These enhancements are coming. There’s nothing we can do about it except make it positive. I see ways in which emergent structures can make this world a much better place, but I also see ways in which emergent structures, fighting state power, turning violent, could make a completely gray, featureless, terrible planet where anyone who was different was instantly destroyed. I think that’s what our network could do in the worst case. I’d rather it didn’t do that.

Audience 2: Not so much a question as a comment. I would like to encourage in addition to reading those books that we need to learn and remember more about our own history, including our very recent history. It disturbs me that there are books about cryptographic algorithms, there are books about early days of hacking, but I talk to people younger than myself who are in their teens and twenties, and from the people I’ve talked to there is an astounding lack of awareness of say, the first crypto war. Nobody that I know of who is significantly younger than me knows about the Clipper chip, or Fortezza, or how we got open crypto with the combination of the expiration of patents and some of the other free software that developed. The period of 1988 to 1992 as a collected history seems to be blank.

Quinn: So let me actually build on that real quick—

Audience 2: I find that profoundly disturbing.

Quinn: Can everybody in the room who has some sort of computer science degree or related degree put up your hand? Keep your hands up. Now, everyone who read Claude Shannon in school put your hands down. So all of you are people with CS degrees who didn’t read Claude Shannon, one of the most fundamental voices in everything you do. And that kind of goes to this interesting point about understanding our history. I think one of the great things you can do is talk to old people. Ask them what life used to be like.

Audience 2: I will talk your ear off about this because I have friends [inaudible] to it

Quinn: But let’s make sure other people can actually talk.

Audience 3: So you talked about the view of the states while the state itself is just some sort of technology to keep society or humankind working. I really enjoyed your talk. I was thinking whether you had thought about the possibility that some sort of new technologies we are inventing, building, may even supersede state structure and even more fundamental[ly] change how humans interact on the global level.

Eleanor: While we could and may replace the state, I really like roads. One of the things that we often end up doing, and especially in the geek community, we will end up building technologies which, well they sort of mostly work. That doesn’t cut it for water systems. That doesn’t cut it for a lot of the stuff that keeps us alive. I don’t think it is unreasonable to start the project of trying to replace the state. I definitely don’t. But we need to make sure that we get it right, because if you fuck that one up too badly things get really really horrific.

Audience 3: I completely agree, but I was just, I thought this talk was a bit focused on the state while the state for me is just another technology, and—

Eleanor: The state is the technology that has kept most humans alive for most of recorded history. So it’s reasonable to spend a certain amount of time on it.

Audience 4: Thank you for a brilliant talk. Basically for me it boils down to this, so instead of a question: People don’t be scared, be prepared, don’t be predictable.

Presider: Questions are short sentences with a question mark, and could you please quiet down some. The people who are watching the stream are complaining about the audio quality because of the noise of people entering and leaving. So either come and take a seat, be quiet, or just leave. Thank you. And the next question, we have one last question.

Audience 5: So actually, I am afraid, I’m very very afraid. Because I feel like we’re walking on a very very thin line, because the actions that we take could easily tip whatever will happen in the favor of what we want or what we don’t want. And I feel like even when I look backwards in history it’s never been like this, that I basically when I try to create something I might later wake up in a scene of a dystopian movie where all I have created ends up destroying all that I love. So how can I not be afraid?

Eleanor: I think that was always true. But you were going to be dead before it happened.

Audience 5: That’s awesome.

Quinn: I want to tell you quickly about Fritz Haber. Fritz Haber is a guy who dedicated his life to inventing as many horrific chemical weapons as he could, and along the way he worked out nitrogen fixing. Which is why we have all these people. And what’s really interesting about that to me… Things like Fritz Haber is one of the people I keep in mind when I think to some degree we have to let go of the fear because I think we will never actually control the good or ill we do in the world. We can nudge, we can push, we can hope, but at the end if the most amazing boon to human life came from a guy who was trying to invent chemical weapons, no one’s driving this crazy train.