Hi everyone. I’m Sarah Brin. Thanks so much for having me, it’s fantastic to be here.

As Sophie mentioned, I’m an art historian and a curator. I’m based at the Pier 9 workshop facility in San Francisco, where work as a public programs manager. But before that, I did a lot of other stuff. And growing up, and even in my younger adulthood, I never ever thought that I would get to have a creative profession. I always thought that people who got to do that kind of work were luckier, or smarter, or cooler. But it turns out that feeling of intense discomfort, of not belonging, is sometimes how people, including myself, develop new ways of doing things.

So, with that in mind I’m going to speak very briefly about three things today that kind of shape my practice as an antidisciplinarian. The first is my understanding of what it means to be antidisciplinary, and kind of how I came to integrate that into my practice. The second is about my interest in experience as an art form. And finally, I’ll go into a little bit of detail about the projects I’m working on currently that involve integration of art, technology, and industry.

So, what does it mean to be antidisciplinary? To me, it means struggle. Sometimes, working in interdisciplinary fields, I felt like I’ve maybe tried really hard working and working and working on a project, and I wasn’t seeing any difference. Sometimes people would look at me and be like, “What are you even doing?” Kind of like this little guy right here. So, to me antidisciplinarity means not only not working in one specific field, but rather instead drawing from elsewhere to imagine something new.

And so I wanted to give you all an example of how I learned to do this, and I thought oh, what’s a better example of thinking about how you don’t fit into something than high school? So that’s me on the right. As you can tell I had a very cool haircut.

I went to a very special high school, although it doesn’t look especially special in this photo. But part of what sort of set it apart was that it was an interdisciplinary magnet program. It was a public school. And so everything we studied, we took an interdisciplinary approach to.

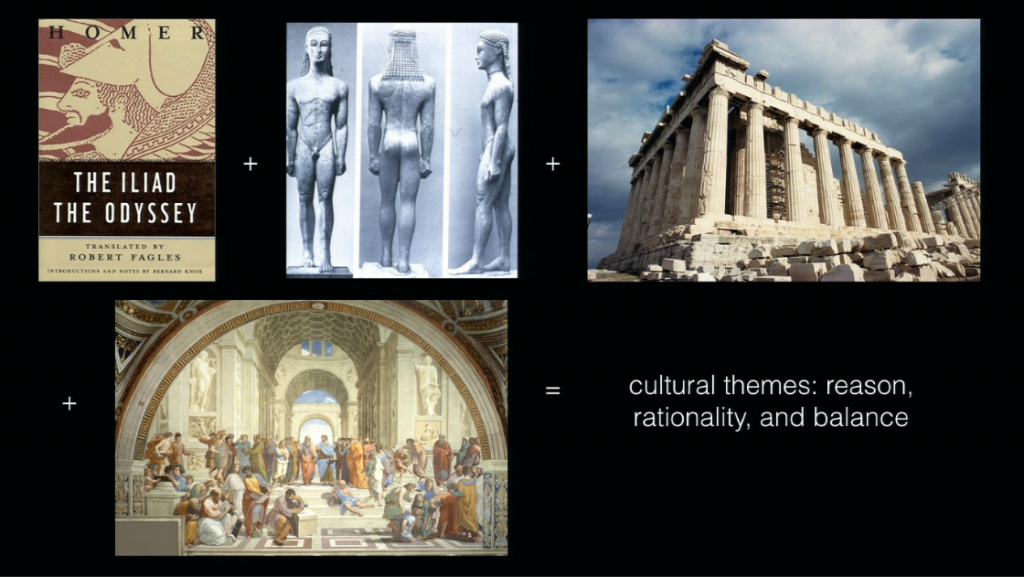

So, this is an example of how we’d do this. Say we were studying ancient Greece. And so we would study The Odyssey in our literature classes. In our history classes, we’d study kouros figures. And in our philosophy class, we learned about Aristotle’s definition of virtue. And in our history classes, we learned about Greek democracy. And we always did this by weaving together seemingly disparate areas of culture by finding themes that united all of them. And so this would continue to shape my practice for a very long time.

So, okay, why am I talking about something that happened fifteen years ago? Why am I talking about high school now? So yes, it was important because I learned actual facts and pieces of arguably relevant information. But more importantly, I learned to think laterally. So I learned to think more comprehensively about an experience of culture rather than isolated phenomena.

So I brought this approach with me to college. I themed my semesters. That means I would take multiple courses, focus on a particular time period or region, including philosophy, art history, literature, etc. This is also when I started to study art history more formally. So, I learned very early on that I have an allergy to formalism. And as my favorite professors taught me, art isn’t just about form. It’s not just about what things look like. Artworks are lenses to give us a look into our particular moment of culture, to look deeper at a real human’s personal experience of a particular moment.

So at this point I already knew that art, history, science, and every other capacity of culture were all deeply intertwined. But I also became very interested in this idea of experience. Both the experiences of the artists, and the public’s experience of an artwork. And I felt like this would shape my research practice in graduate school, and it did. And I moved on to study at the curatorial program at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

So, as soon as I got to USC, I noticed that I felt very very isolated from most of my peers and my colleagues in my program. And part of that is because art is a very privileged discipline. And USC has reputation for its very privileged student body. And realizing this, I felt like I had made such a huge mistake going to art school. I realized that all my classmates look like this. They all had very complicated shoes. I felt like they had families that could pay for them to do unpaid internships at fancy galleries. I thought, “I don’t belong here.”

But I quickly forgot about that when I found video games. In 2009, there was a very pivotal moment for artist-made video games. Roger Ebert had just made his very controversial claim that video games could never be art. And simultaneously, there were all the students at universities like Parsons, NYU, and even ITU Copenhagen, who were really changing people’s ideas of what video games could be. I didn’t grow up playing video games, but I was so moved by this. I loved the idea that games were accessible, games were ubiquitous, in a way art couldn’t it be. So, I wanted to reach out to people with art, and I wanted to do this by using something familiar. I wanted to reach out to the same kinds of people who might’ve felt isolated by art in the same ways that I might’ve I felt.

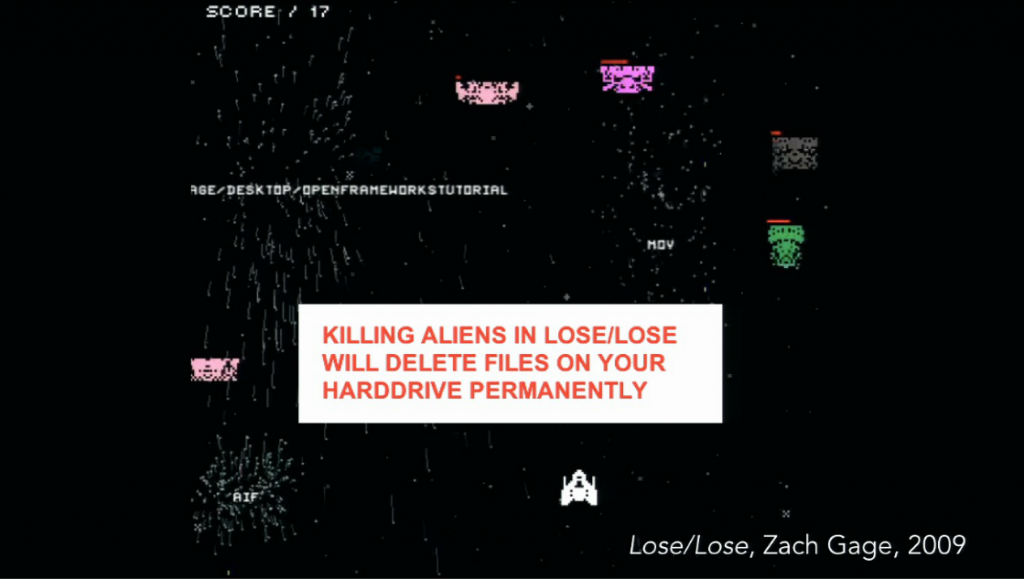

And so I started to research and curate experimental games that challenged the popular conceptions of the medium. These weren’t racing games. These weren’t fighting games. These were games that completely blew everyone’s expectations away. This is actually from a game called Lose/Lose created by an artist named Zach Gage. It looks just like the video game Space Invaders, except for every alien you kill, you randomly delete a file on your computer. This is a pretty unusual concept because normally when you take actions in games there are no consequences in real life. Not so with this project. And I thought that was so, so, so fascinating.

But my classmates and my professors were extremely skeptical of this. And they often discouraged me from moving forward with my studies in games. But slowly, laboriously, I knew how to legitimize my work by providing historical precedents and cultural context for the projects. And so gradually I was invited to do more and more curatorial projects with museums and institutions like the SF MoMA in San Francisco, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. And my work became harder to dismiss.

This is an example of one of my games projects, which we called “Horizon.” It was a press conference and exhibition dedicated to experimental games, including a Swiss project called “Laser Cabinet”, which you you see up here, by artist named Khalil Kloush. And it’s a lot of fun to do

This is from another project called “Ahhhcade” that we did in 2013 at the SF MoMA in collaboration with Babycastles, an artist-run space based in New York. This show was called Ahhhcade, and it was a show of meditative and non-competitive video games.

So, I worked with a lot of independent curatorial projects with video games. I did some arts journalism. I worked in an education department at a museum. But it was all very very piecemeal. I was always kind of looking for the next thing, trying to figure out how I could piece all of my interests together to make a living. And I did that for a long time, and then I was invited to come work at Autodesk Pier 9 workshop.

Autodesk, as Sophie mentioned is a software company that makes these products, as well as many others. And we make design software for basically every industry you can imagine. We have offices all over the world, including in Neuchatel.

And this is our office! It’s pretty cool. That’s where I work. It’s Autodesk’s digital fabrication facility, and that’s where we really have an opportunity to refine the connection between our design software and digital fabrication machines that bring those designs to life.

So when I talk about digital fabrication, what does that mean? That can mean a lot of different things. Here is a CNC mill. So if you take a look at this big blue machine up here, that’s our DMS 5‑axis mill. The way that works is we start with a digital design in a software program, and then we put a block of material into the mill, and the mill will subtract material away to make that design come to life.

In addition to the machines in our CNC lab, we have a laser lab, and 3D print lab. We have an electronics lab. Textiles area. A test kitchen. Wood shop, metal shop. We have all kinds of stuff going on. It’s pretty spectacular. So, that workshop, among serving many other important functions to our company allows us, my team, the creative programs team, to showcase our products by partnering with other creative entities. So, sometimes that means external partnerships, and sometimes it’s through our Artists in Residence program.

The Artists in Residence program is kind of a misleading title, because over the past few years we’ve welcomed over two hundred architects, chefs, fine artists, furniture makers, fashion designers, to really push the boundaries of our software and of our tooling. They are interdisciplinary provocateurs, who are invited to collaborate, research, and test the limits of what’s possible. One of my favorite artists was working on a project on the DMS (that big blue machine I showed you just a minute ago), and he actually drilled through the materials bed of the machine, with the machine itself. And he was really worried, he’s like, “Oh, no. Am I going to get in trouble?” And instead he just got a bunch of high fives because we were all like, “Well, now we know not to do that.” And so that’s kind of how what our space feels like to be in.

This is actually an example of what he was working on. This piece is called “Smaller & Upside Down.” [dedicated site] It’s a series of facial distortion lenses that are 3D printed and CNC milled. As you can see, the effects kind of mimic what you might find in Apple’s Photoshop. And these are applied for public art installations.

Another project I really love is the collaboration [at Coby Unger’s site] between an artist named Coby Unger and an eight year-old boy named Aidan Robinson. Some of you probably already know that prosthetics are very very expensive. And if you have a kid who’s growing, they’re going to grow out of that prosthetic, too. So what Coby did is he partnered with Aidan to develop a series of attachments for his prosthetic, including a Lego arm, a Nintendo Wii controller, and a violin bow. But in addition to creating these really amazing attachments (Aidan referred to himself as a superhero cyborg) Coby developed a 3D-printed socket for the prosthetic that as Aidan grew, he could heat it up and resize the socket to grow the prosthetic along with the child, which is pretty neat.

A final project I’m going to talk about is a series by an artist named Morehshin Allahyari. The series is called Material Speculation: ISIS. [at Morehshin’s site] And what Morehshin does here is she uses our Objet Connex multi-material printers to recreate artifacts that were destroyed by ISIS. Not only are the models exact recreations of the objects in terms of definition and style, but also there is a 3D model file embedded within each of the objects. So this is an extremely daunting task, because these models didn’t exist previously. So what Morehshin had to do was create these models based on photographs and extensive consultation with experts around the world. Part of why I think this project is so fascinating is because it’s not just an artwork. It’s an archive, and it’s activism.

So okay, why did I talk to you about these projects? Thinking back to what I mentioned earlier, the idea of context, of experience, of public engagement, all of these artists are aren’t exclusively artists, they’re antidisciplinarians. They’re working together to solve problems. And they’re borrowing from multiple preexisting fields, while using new technologies to create creative solutions. And perhaps more importantly, these new ideas are inviting. They’re public-facing. And they ask for a response.

So, thinking about the work all of these artists are doing, and some of the projects that I talked about earlier, it’s not always easy to look for new types of solutions, for new types of problems. Sometimes it can be extremely difficult and extremely uncomfortable. But I thank you, and challenge you, to look for that own discomfort in yourself and apply it to your practice.

Thanks.

Sophie Lamparter: It’s a really fascinating place. I swear, if you have the chance in San Francisco, maybe we can get a behind-the-scene tour, let us know. It’s really worth going and seeing how they really embrace innovation, interdisciplinary and anti-disciplinary. So, I don’t know. Is there one example, or one project, or I don’t know, one idea that completely blew your mind? That the whole team was like, “Oh, we’ve never thought of that,” or somehow changed a bit the perspective of the tools or…

Sarah Brin: Yeah, we have we have a bunch of artists who are always collaborating with each other. And what’s really unique to me, coming from a more traditional arts background, is that artists tend to be very protective of their ideas. And there’s also this idea of secrecy. And so frequently, when we see artwork in a museum, we’re looking at the finished object. We’re not talking about process, because kind of the secret sauce, right? So we have all of these artists together at one point in time that are sharing ideas, sharing their challenges. They’re helping each other, they’re collaborating. And I think that really shows, and I think personally it’s important to me that we’re developing new forms of culture, inclusively.

Lamparter: I agree. It’s also great, each time you you have a meeting with somebody at Autodesk, they show you their personal project, because most of the employees are also collaborating at night or on the weekend on, I don’t know, 3D printed music instruments, or whatever they enjoy. And I think that’s also very very special. Thank you so much, Sarah.

Further Reference

Enter the Anti-Disciplinary Space session details at the Lift16 site.

Citations

- Anthropogenic Narratives. Communicating and Experiencing Non-Human Perspectives

- Le molteplici specificità del design della comunicazione. Una disciplina aperta

- Multidisciplinary Aspects of Design Objects, Processes, Experiences and Narratives, “Open Communication Design A Teaching Experience Based on Anti-disciplinarity, Thinkering and Speculation”

- To Prototype to Learn Fronting Uncertainties. A Pedagogy Based on Anti-Disciplinarity, Thinkering and Speculation

- Vídeo-cartAgrafiOs: a Experiência Metodológica das ‘Vídeo-Cartas (não) Filosóficas’ Tecidas na Pós-Disciplinaridade