Thanks, David, and thanks Massimo. It’s great to be here. It was eleven years ago that Massimo and I were at the summer school for history of science and Catherine Carson was there as well.

At the heart of everything I’ll talk about is a real hands-on project, something that you can do at home and I would encourage you to try this, or to try some other manual engagement in order to reach a deeper understanding of media and their history.

I’m going to start by explaining how to knit Morse code. Then I’m going to step back and show you doing something as odd as knitting Morse code can increase understanding of mathematics, of communication, of media, and of the histories of each of those things.

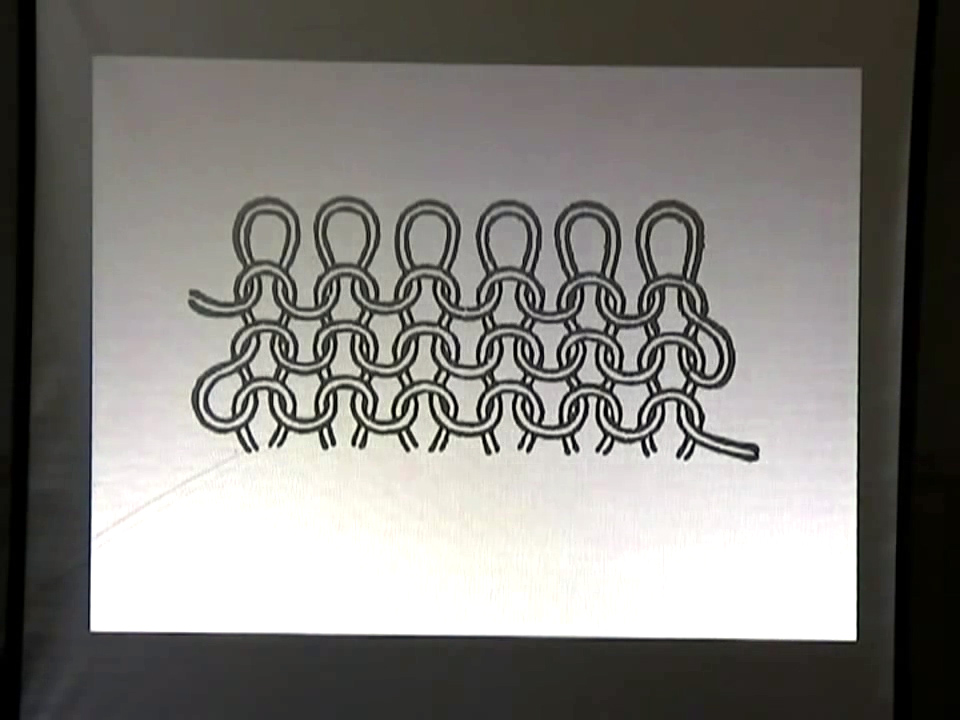

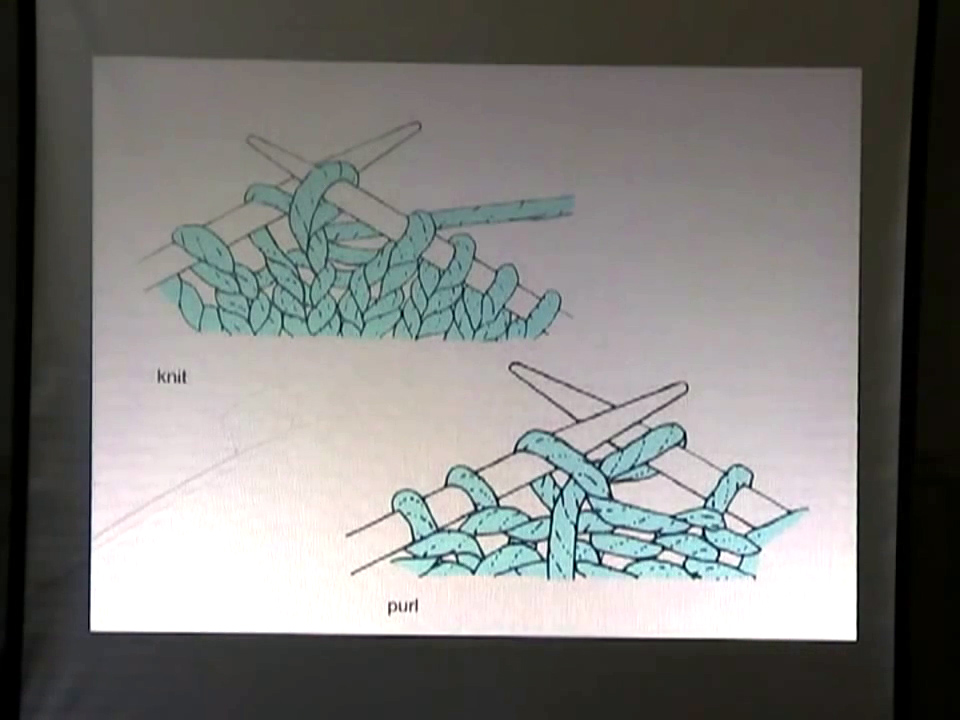

Knitting is an ancient technique for making a fabric out of a single yarn by interlocking loops. So if you have an existing row of loops, each loop is lifted, you make a new one, and you slip it under an existing loop. And this gets done repeatedly.

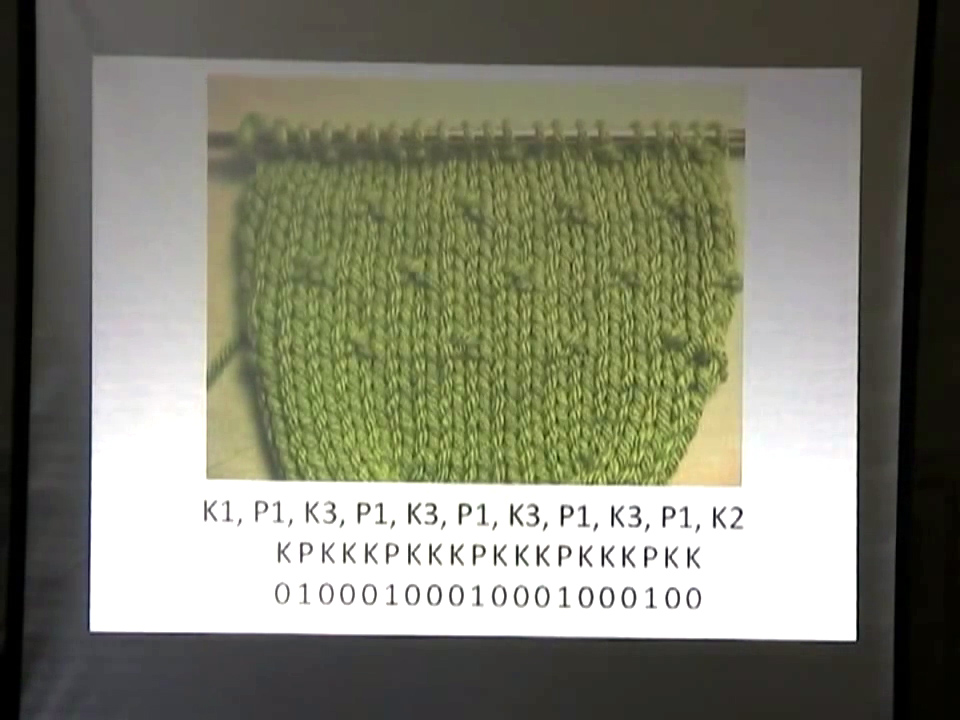

There are two ways that you could slip a new loop into an existing loop. You can either be pushing the existing loop to the back of the cloth, in which case you’re making a knit stitch. Or you can be pushing the existing loop to the front of the cloth, in which case you’re making a purl stitch. In other words, these two basic stitches in combination create all kinds of decorative designs, and so I want to call knitting a binary operation.

Which people sometimes find hard to swallow. So to make this a little easier to accept, I’m going to write this in the kind of binary format that we associate with electronics. The first line that’s here describes a line of the seed stitch pattern is how you would see it in knitting instructions. They will condense groups of knit stitches to call them “K3” for three knit stitches in a row. In the second line I’ve just expanded that, and in the third line I’ve made a choice to represent a knit stitch with “0,” and represent a purl stitch with “1.” You’re going to have to stop by your local knitting store for the details of how to knit, but that’s the way in which knitting is binary.

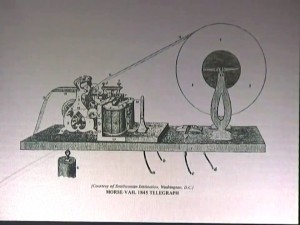

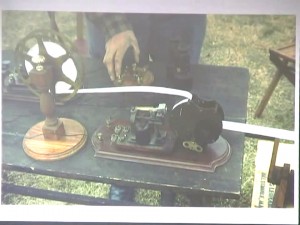

In the 1800s there were many different ways for communicating by electrical telegraph. Samuel Morse developed a code in the 1830s that became dominant, and the reason his code caught on was that its simplicity made it very robust. His code operated by switching an electrical current on and off for moments in time. The code was designed to be visual and to produce a permanent paper record. So this round object on the right-hand side of the drawing is a reel of paper tape.

What happened was this paper tape would roll past a stylus at a constant rate. If an electrical signal was telling that stylus to engage at a given moment, it would leave a dot on the paper. But if the electrical signal was held on for a longer period of time and the paper tape is rolling by at a constant rate, it would draw out a dash on the paper.

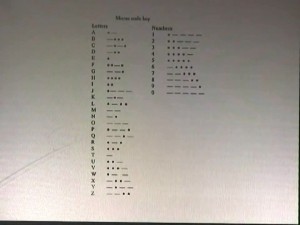

Then the telegrapher would use this code that associates dots and dashes to letters and numbers, and also punctuation, which don’t happen to be on this particular code, in order to translate a message from dots and dashes back into words.

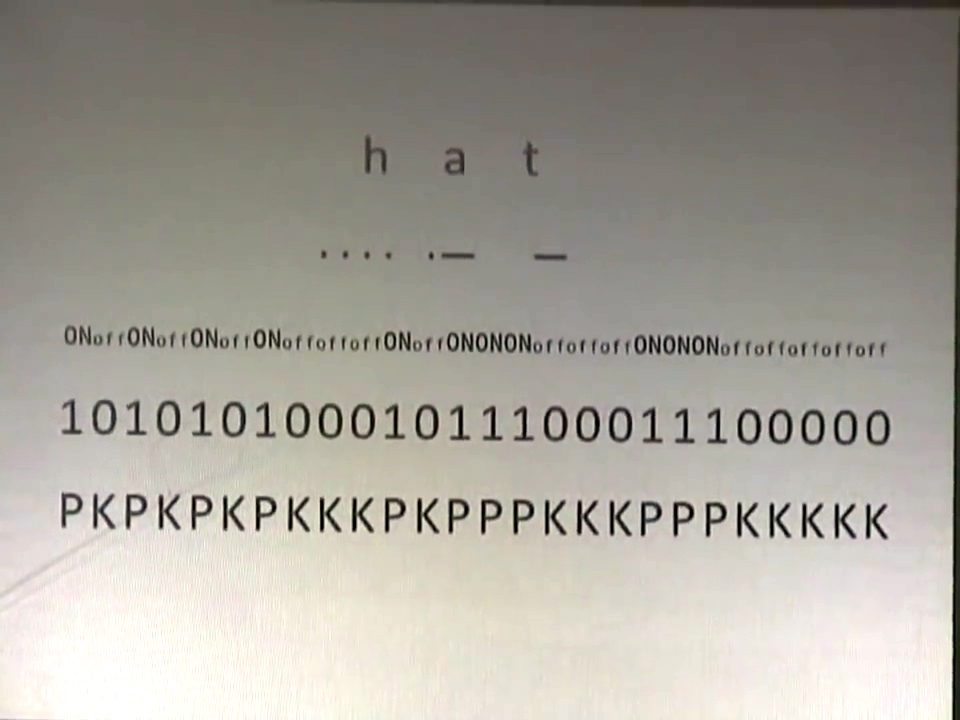

Like knitting, Morse code is built out of two fundamental units. The two parts, though, are not these dot and dash, but rather the two possible answers to whether a stylus is engaged at any given moment in time. So if I write out the word “hat” and translate it into Morse code, and then what I’ve done on the third line here is to say whether the stylus is on or off at a moment. So if I want to make the four dots that make up the “h” in “hat,” then I want the signal to be on then off then on then off, on then off then on, and then this is important, three offs. Three moments of “off” because that’s going to signal I’m at the end of a letter and the start of a new one. And then translating the on and off part to something that looks like binary electrical code is pretty straightforward. Here I’m going to choose 1 for “on” and 0 for “off.”

Because I’ve represented the knitting and the Morse code both in this system of 1s and 0s, it’s probably pretty obvious how I then combine these two things. I’m just going to take that 1 and 0 line that I’ve got for “hat” and push it back to the purl and the knit stitches.

That is the basic method by which I put Morse code into a number of different objects.

Image: InVisible Culture, “Knit for Defense, Purl to Control”

[sweater credited as “Subtle Distress”]

This is the simplest piece. It’s the SOS Sweater, in which this emergency call which is made up of three dots then three dashes and three dots is repeated down the front center of the sweater. This ends up looking like rib knit. Well, it is rib knit. In fact, a knitter would say, “What do you mean it’s dot dot dot? That’s a 1 by 1 rib knit, followed by a 3 by 1 rib knit, followed by a 1 by 1 rib knit.” And that just shows you again how these systems can go back and forth between each other so simply. That easy translation between knitting and Morse code, things which on the surface seem to be so very different from each other, starts to reveal why a binary system is so powerful.

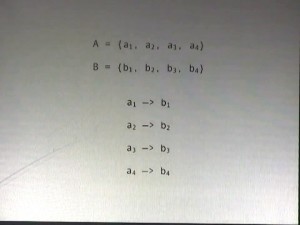

Between any pair of systems of the same order, that is systems that have the same number of elements, there is an obvious seamless translation. You’re just going to assign each element of one system to map to one element in the other system.

What makes binary systems particularly useful is that their elements can be associated to the fundamental dichotomy of existence and non-existence, such as the presence and absence of an electrical pulse at a given moment in time. Most of our current computers depend ultimately on extremely complicated and extremely numerous combinations of binary instructions that address the same question over and over: fire a pulse of electricity right now? Yes or no.

One of my motivations for knitting Morse code is a sort of popular math one. I want to increase understanding of binary systems. I actually used to do mathematics for quite a while, and I taught mathematics and I guess I still have that sort of math geek vein in me. But I believe that there’s a certain kind of power that comes with the knowledge of how machines work. In a time when our society is communicating by using digital electronic techniques, and analyzing with digital electronic techniques, and entertaining ourselves with digital electronic techniques and so on, I think it would be beneficial for people at least to understand what does that mean? What’s a digital electronic technique?

I also think that if users of media had some conceptual knowledge of binary systems, it could lead to a better user experience. And I’m very open here with what I mean by better. This could mean a more satisfying user experience, it would mean a more productive one, it might mean a more critical user experience. But I think it would be better informed, regardless.

This translation that I’m making from Morse code to knitting is intentionally playful. It’s an exaggeration to show just how far a binary-to-binary translation can be pushed. And because knitting is warm and fuzzy, this mathematical topic becomes a little more approachable.

There’s also a benefit here in bringing together two dissimilar binary systems, and this gets at one of the other reasons that I did this project. Morse code knitting, as Massimo said, is a component of a larger study that I’m doing on the culture of binary systems across many centuries. One premise of that historical investigation is that the powerful adaptability of binary systems is revealed partly through their diversity.

Just take the example of knitting and Morse code. Different people tend to know these things. After Morse code fell out of use in telegraphy, which in the US was around the 1910s when it became automated, there were basically three groups of people who knew was Morse code was. Boy scouts, military personnel, and two-way radio hobbyists, each of those groups being predominantly male.

Knitting, on the other hand, since at least the 19th century has mostly been done by women and girls. The gender division in the knowledge of those two binary systems was very well illustrated by an interaction I had very early in this project. I had a fellowship at this international artist’s residency program and they were having an open studio night. They were encouraging people to open their studio and show what they were doing. I didn’t have much together yet. I was still planning this project. But I decided that I would make a small knit Morse code document as I went through everybody else’s open studios.

So here I’m listening to a violin performance, in the back row trying to be unobtrusive. At one point during the evening a couple approached me. They were probably in their early 70s, and they asked me what I was doing. I managed to say that I was knitting Morse code and my German broke down pretty quickly after that because I had to pause to explain why in the world am I doing this and what does this mean.

While I was paused, something really amazing happened, which was that the woman started to point out the different stitches, and they’re talking back and forth and the man eventually read a couple of words out of this piece of knitting to me. So I know they weren’t bluffing. He read this document, and unfortunately I don’t know exactly what they said to each other. If my German were stronger I wouldn’t have given them enough time for all of this to unfold. But I found this to be a great demonstration that traditionally feminine knowledge and traditionally masculine knowledge could unite to decipher this very strange document.

Within the framework of this broader project on the cultural history of binary systems, if you start looking at different times and places, the associations with and the uses of binary systems, are astonishingly varied. They go far beyond gender.

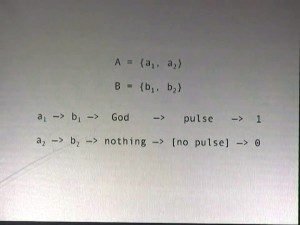

Leibniz, the German philosopher-mathematician, was the first European to write about binary systems. He investigated their potential for analysis in mathematics and logic, the kinds of things you would expect of Leibniz. He also, in one of the most unusual applications of binary systems that I’ve seen so far in my research, proposed that binary could be used for cross-cultural religious conversion. So when I had “God” and “nothing” up on that previous slide that was not a joke, that’s directly out of Leibniz.

Leibniz wrote several letters around 1700 to Jesuit missionaries who were mathematicians serving in China. He proposed to them a way that they could maybe convert the Chinese emperor to Christianity. Missionaries had made some progress with the emperor, but he just was not buying the Christian story of creation. Leibniz knew from the Jesuits that he was in correspondence with that there were points of binary analysis in ancient Chinese philosophy. He also knew that the Chinese emperor was interested in Western mathematics, and Leibniz was working on binary systems. So Leibniz told the Jesuits they should appeal to this Chinese precedent and to the emperor’s interest in Western mathematics, and to argue by analogy. He said tell the Chinese emperor that if he can accept that all numbers come from 0 and 1 (you can build every single number) then he should be able to accept that God could make the whole universe from nothingness and the unity of his being. This is actually a creation explanation that even I can almost accept.

One of the Morse code knitting pieces that I made contains the text from one of Leibniz’ letters, and I tried in my knitting to do what Leibniz was doing by referencing ancient Chinese philosophy, which is to package it in a way that eases cultural acceptance. So this is in the shape of a Chinese hand scroll. It’s made out of silk, it’s 88 stitches wide which is a number that’s symbolic of double prosperity in Chinese culture, and so on.

Leibniz’ argument for the Christian creation story based on binary structure shows that just about any characteristic can be linked to binary systems. I’m almost always asked, when I tell people I did this project, especially when they see some of these pieces, how long it took to make these things. This one actually took the longest, although it’s by far not the largest. I didn’t keep track. I couldn’t if I had any intention of finishing this project. It took a ridiculous amount of time. Suffice it to say that I did it while I was blissfully unemployed. But even if you don’t have the pressure of a ticking tenure clock, it’s a reasonable question to ask, why would you actually knit Morse code? Why do this by hand (the whole thing is by hand by just me) instead of writing an article about this as being a possibility?

That gets into the way that I feel that the Morse code knitting constitutes a kind of study of media, and particularly a popular study of media. I want to reach a broad audience. I want to expand who’s participating in the discussions about media. Analogous to what I said regarding the importance of some popular understanding of binary in a digital society, I think that it’s essential to expose and to talk through questions related to media, beyond the academic circles that we sit in.

These knit objects have a tactile and a visual allure that I can say in all humility is greater than that of a scholarly article. Again, the coziness of knitting helps in that regard. But the puzzle element is also appealing. Once people realize that there’s some kind of message in these objects, they’re very curious to know what the knitting says. And their desire to uncover the secrets engages an audience in an activity of understanding the Morse code knitting.

One thing they’re going to get out of that Leibniz scroll is a nice little history of science lesson about how important the early modern Jesuits were in spreading scientific knowledge internationally. But all of the rest of the pieces in this project bring up ideas of communication and media.

At the most elemental level, the Morse code knitting highlights that retrieving information requires knowledge of multiple cultural codes. If you attempt to read—whatever that means—this Morse code knitting, you have to proceed in steps. You’ve got to interpret the knit and purled stitches into dots and dashes, then you’ve got to take that Morse code data and translate it into letters. And then depending on your language skills you have to perhaps translate the German of the Leibniz letter or the English of the other pieces. That requires a lot more patience than reading a text.

But think about what you’re really doing when you read a text in which you’re…even one you’re fluent in… You have to understand how the text is laid out on the page, what’s the reading direction, where do I start? What the characters are, how they represent sound, the combination of sounds into words, the association of words to ideas. It’s complicated, and we take it for granted so easily. But all access to the content of a medium depends on complex cultural codes, or call them skills. But there’s always work involved to get that message out.

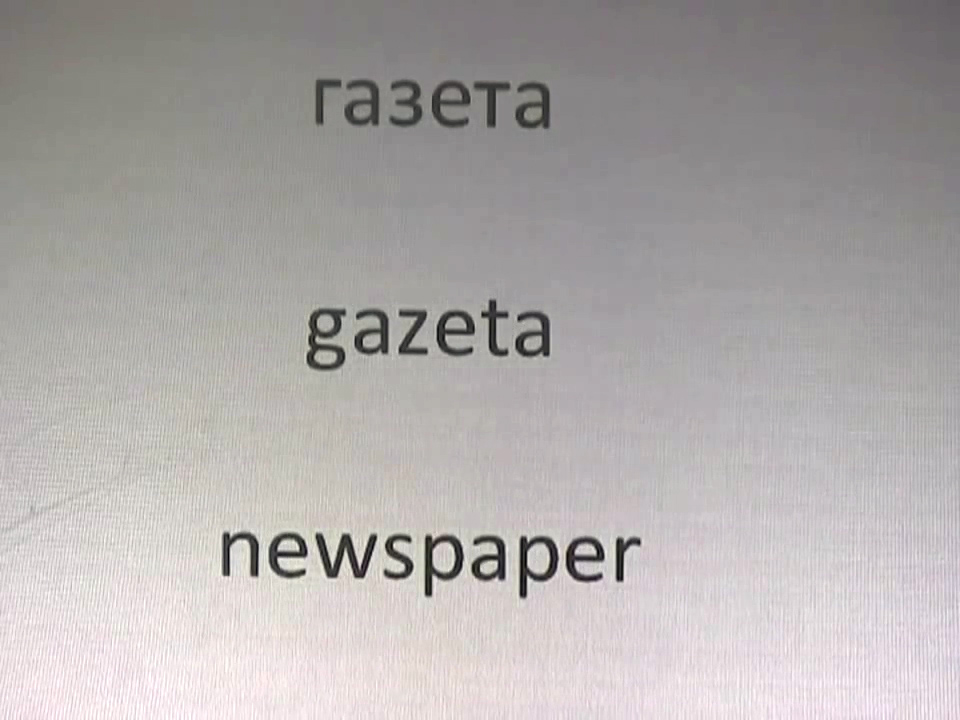

A second linguistic concept that comes from the way the Morse code reading slows things down, or I should say the Morse code knitting slows down reading, is that it ends up separating the visual and the cognitive aspects of written communication. When you’re literate in a language, the brain will leap instantly from a printed word to meaning. But look what happens in the absence of literacy. Personally, I don’t read Russian, so when I see a word that’s in Cyrillic characters I get stopped at the level of image and my brain will see things that it doesn’t see in that bottom line. It’ll recognize shape and pattern. In the middle line, which is transliterated, I’m still going back to an early reader stage where I might have to sound out the word or I will at least look at each letter.

Morse code knitting ends up enhancing the visibility of language by diminishing readability. The multi-layered process of finding language behind the knitting is slow enough for the “reader” to notice a distinct sequence of component activities. To stop taking for granted all that stuff that goes into reading. In that way, the close inspection required to read Morse code knitting raises awareness of the difference between a message in terms of idea and concept, and the signs that are used to transmit a message through a given medium.

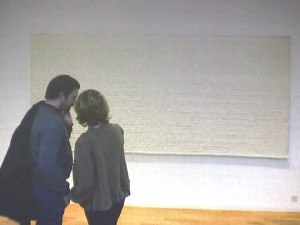

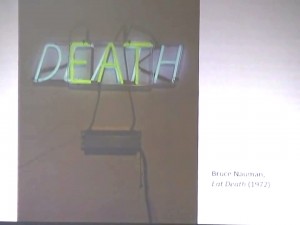

This sort of attention to the play between image and signification of language ends up linking Morse code knitting to word art. By that category I’m referring to work where language gets used as a visual medium. These are just a couple of pieces which you might have seen before, and there’s a whole genre like this. It starts in the United States around the 1960s.

I got interested in what was going on in word art and I started wondering what would happen aesthetically if you take an existing piece of word art and you make it really hard to read. So I wanted to produce something that was already out there into the Morse code knitting. The piece that I chose as the source work is Jenny Holzer’s Truisms. This is a project in which Holzer wrote a series of about 250 very pithy statements and then she would produce selections of them. She did this on t‑shirts, she put them on electronic billboards. It’s amazing that she got the consent of Caesar’s Palace to do this, but that was not the only one shown there. It was a cycle of several of them. And she had them engraved and carved into benches, and she put this in lots of different places, in lots of different formats, which is one of the reasons that I felt it was a reasonable thing for me to extend this into knitting.

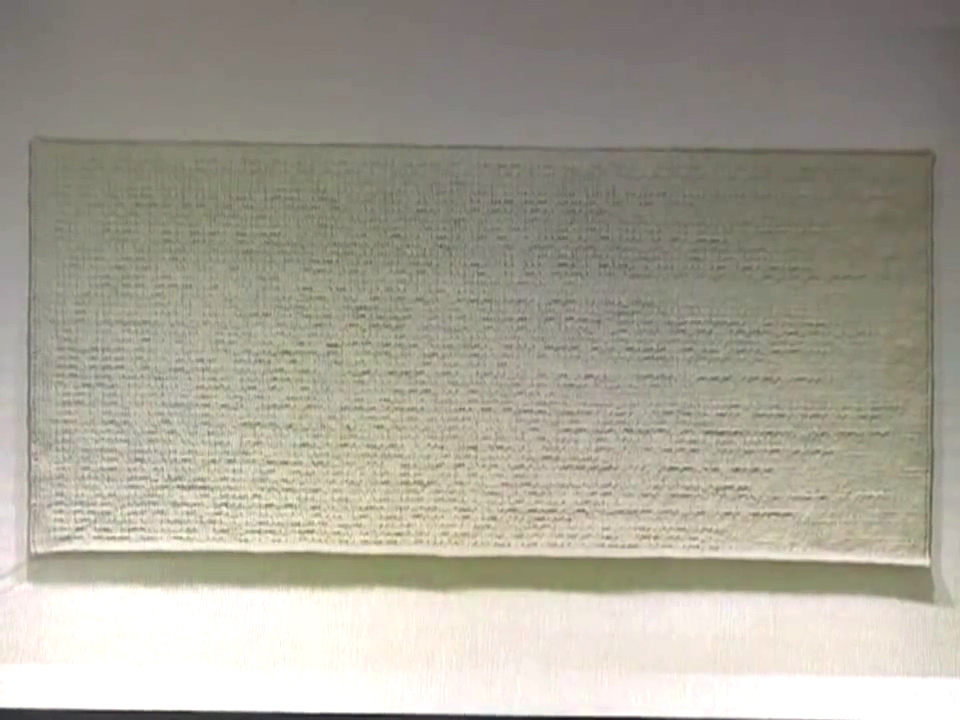

This piece is twelve feet wide, approximately five feet tall. This contains a group of the truisms according to the rules that she had for the project. And the rules that she had in place also made her work very well-suited to presenting in horizontal rows of knitting because what hopefully you can see here is that she would represent each truism on its own line whenever that was possible. Here I had the room to do that, and that means that on the left hand side you’ve got a flush margin and on the right it’s broken. So even if you don’t know that this has text in it, it kind of feels like text.

Additionally she would always take whatever selection she had made of the truisms and put them in alphabetical order. So again, you don’t have to know that this is in Morse code. You don’t even have to know that it’s text of any sort, but if you were to study it very closely, you would see that there is a pattern in which certain lines that start with what turns out to be dot-dash, the letter “A,” those lines are all at the top. It would be a heck of a Rosetta Stone puzzle to get through it I think, but someone could do that.

These points about the signification and the coding of language I feel sit within media theory generally.

The next point that the Morse code knitting raises is related to the history of media. There are many tales about information being carried through textiles in lots of different cultures. The oldest one that I’ve come across is the Greek myth in which Philomela has been raped, had her tongue cut out, and imprisoned, and she has no way of communicating what has happened to her. Except she has a loom. So she weaves her story into a piece of cloth, has the cloth passed to her sister, and the sister can understand the information in the cloth.

These span many centuries but go right to the present. Just a few years ago, there was a movie produced Hollywood called Wanted which tells of a group of assassins who get their kill orders from the “loom of fate.” The loom of fate will use a binary code to put people’s names into a piece of cloth that it’s weaving.

With respect to the history of media, I consider all of these stories about messages hidden in textiles to be evidence of a very long tradition of flexible thinking about what could constitute a medium of communication. That is, people have been creatively imagining how to transmit information for a very long time, and some of their methods that they suggested work perfectly well without an electronic network.

I don’t have time to explain this piece in great detail but briefly this is a sweater I made for myself that has text in it that’s personally meaningful. And because it’s in a code I can both have it wrapping me securely, but I can be in public and have this message kept private. It’s also a perfectly functional way to pass secrets. A spy can show up wearing a sweater that’s got information in it, probably passed through all kinds of searches for the microdot or what have you, and if any suspicion is raised about the sweater as a source of information you can unravel it really quickly and all the information is destroyed.

The legend about messages hidden in textiles that I most wanted to realize in the knitting was live recording of information. So in Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, a novel from the late 1850s, there’s a character named Madame Defarge. She ends up serving as a strange sort of secretary for a group of French revolutionaries because in her knitting she hides the names of the group’s adversaries. She gets away with doing this in public because she just looks like this harmless woman knitting.

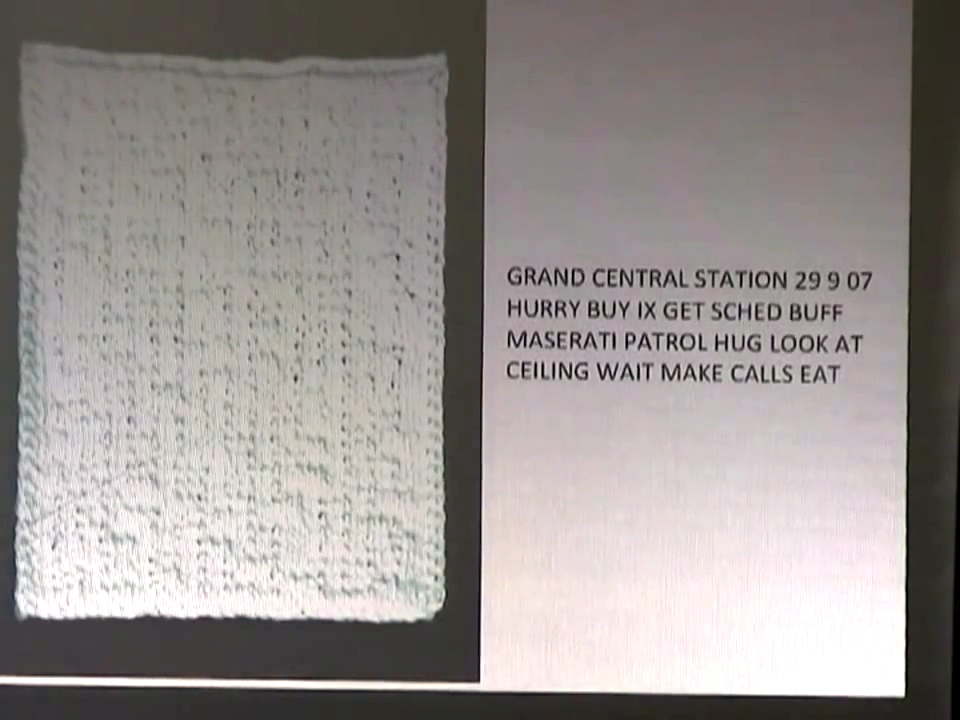

So I made four pieces in this recording series. The first was at this open studios event in Stuttgart, and three at iconic public spaces in New York City, at Strawberry Fields, the memorial to John Lennon in Central Park; every scholar’s favorite site, the main reading room of the New York Public Library; and in Grand Central Station.

I made these pieces look like sheets of paper because I wanted to use them in my history classroom to show the complications of documents. These pieces contain errors, basically at the level of typos. They certainly reflect the point of view of the recorder, and they reflect the limitations of the recording method. Morse code is very bit-intensive, so you get this economy of words forced on you and I also completely dispensed with punctuation, which could definitely cause confusion if you try to read this back.

There’s also information in these documents that could be very hard to make sense of. Why in the world was someone buffing a Maserati in Grand Central Station? If you’re reading that document in an archive, you might want to skip over it as being an error just like the error where it says “BUY IX” instead of “BUY TIX” for “buy tickets.” Or, if you wanted to figure out [if it’s] maybe possibly true, you’d have to do a lot of further research in order to find out that on the 29th of September, 2007 in Grand Central Station there happened to be this display of Maseratis, so okay it sort of makes sense they were buffing them and they would be in the middle of things. So someone there to document what was going on in Grand Central Station couldn’t help but notice it. It’s a very weird thing to have in a document about Grand Central Station.

I’ve used these pieces to open discussions with my students about the practice of history. Historical research is challenging enough. Luckily we don’t have to read this kind of knit document when we’re in an archive. But in order to understand the various evidence that has been left by diarists, by bureaucrats, by journalists, interpretation is always necessary. To record events in knitting ends up underscoring how documentation practices shape the historical record. It reminds us that all documentation is incomplete and selective, and that interpretation is essential.

To wrap up these different issues that are raised by the pieces, I’d say that my aim was to capture the interest of a general audience in an otherwise esoteric study. The Morse code knitting is overall supposed to be an entry into this topic of binary cultures. And in the process of uncovering messages that are buried in the knitting, hopefully viewers are encountering various points about communication. We’ve got some snippets here from the history of media, perhaps more importantly there’s an exposure of the continuity of some long-standing challenges with media, meaning I think that I’m demonstrating that some of the concerns we have now about media pre-date our particular technologies. People have been worried about identification and modes of communicating way before electrical communication.

I had hoped to raise all of those points with an audience, and what came as a surprise was how knitting Morse code by hand actually deepened my own historical understanding. For starters, it certainly made me appreciate the clever definition of Morse code. That’s something that you pick up any history of the telegraph and it will tell you that Morse code was brilliant because it was easy to learn. And I’d read that enough times, I guess I sort of accepted it, but I must not have believed it on some level because I never tried to learn Morse code until I got that idea of walking around and making a piece and I couldn’t have my cheat sheet in front of me. At which point I made flash cards and I couldn’t believe it. Within 24 hours, I knew the code.

I still sort of dismiss this. I’m like, “Well, this isn’t what telegraphers did. All I know is the correspondence between letters and their codes. I can’t hear Morse code. I can’t send it at a telegraph key by typing.” I thought I’m still far short of what a telegrapher would need to do to really have the code in their body.

And so I was really shocked when I found myself directly knitting ideas into Morse code. That happened even as I was circulating through the open studio event, just days after I had memorized Morse code. I was attending performances, I was chatting with friends, and I would think a word and just knit it. I know that’s hard to believe and in fact that’s part of why I want to teach people how to do this. I think it’s amazing what the analog, continuous body can do in a digital, discontinuous way.

Making words out of stitches also made me very aware of the bit intensity of Morse code. I was very frustrated at how few words I could get into one of those pages. Appreciating the bit intensity is equivalent to appreciating the speed of a telegrapher. A fast telegraph operator would send Morse code at about forty words a minute. That rate means that each bit of information passed by in three hundredths of a second, or it means that the fingers are doing something very precisely at intervals of three hundredths of a second.

If what you’re trying to do is send a dot and you accidentally depress the telegraph key for nine hundredths of a second, you have instead sent a dash. You have changed the meaning, maybe in a way that looks like a typo or maybe in a way that just garbles the message or changes meaning in a way that it gets misread.

Those are just a couple of the examples of how the process of knitting Morse code informed my work. I’d always taken objects into the classroom. I love to ask my students to think with their hands when they pick stuff up, and I think that these material objects are important to understanding history. But this was the first time that I had made something as part of my research.

I’ve just begun to collaborate with Edward Jones-Imhotep, who was also at this international graduate student summer school at Berkeley eleven years ago, and Bill Turkel on a project that will look comprehensively at making as a research process. This is a method that we’re referring to as “humanistic fabrication.”

One benefit of fabrication is popular engagement. I don’t want the Morse code knitting to be a unique project. I intend to offer a how-to guide. I want to encourage people to explore this or their own methods for putting information into crafts. And given the current, pretty wide-spread enthusiasm we have for making things, I think I can get some people to try this.

I also suspect that the popularity of hands-on projects is what eased reception of the Morse code knitting when it was exhibited. These were hand-crafted pieces put before an audience in a setting for open-ended looking in a place that they could puzzle through things on their own time schedule. There was a sheet that sort of explained what these things were and what the Morse code was and how you could do the translation, and people took the time to do that.

I certainly was not in control of the audience’s train of thought when they were standing in that exhibition room, not the way that you would be in a tightly-structured piece of academic writing, walking a reader through an argument. But I witnessed genuine engagement with some of these questions that scholars are debating. And I’m very committed to including anyone who is curious in the discussion of media, their history, and their consequences.

I’ve straddled a lot of territory. I would really appreciate your feedback on which parts of this work, where I went too far, and any ideas that you have for exposing a cultural history of binary systems to a wide audience, or just for how we can relate scholarship to contemporary issues generally.

Thanks very much.

Further Reference

Kristen’s artist’s statement about Morse Code Knitting.

She also appeared on CBC Spark, speaking about binary systems.

Citations

- Imagining a Soft and Relational Smart Home

- Knitted threads of silence: Anatolian stockings as techno-aesthetic tacit media

- Knotting data as a feminist approach to data materialization

- Making meaning: Roles for craft in rehabilitating liberal education

- Tangled, tangy, microbial threads: Textural methods for rendering past, present, and future sensory memories

- Hilvanar tecnologías digitales y procesos de tejido o costura artesanal: una revisión crítica de prácticas

- Listening space: Satellite Ikats