Felicia Anthonio: You desperately shoot off messages on your phone to find out what is happening. But none of the messages are going through anymore. Your Twitter feed is not refreshing. Even when you open your laptop and decide to try from there, it is useless. Your computer does not want to connect. Even this podcast you’re listening to right now stops streaming suddenly.

No news is coming through. There is no way to find out what’s going on in the streets of the capital, where protests erupted a few days earlier. You knock on your neighbor’s door and ask them if they know what is happening. Have they gotten any news? They can’t get online either.

You realize that the Internet is not down. It has been shut down all, across the country. No one will be able to see or hear what’s happening as they start cracking down on the protesters, brutalizing them with batons, and maybe even using live ammunition this time. The government has flipped the kill switch.

Welcome to Kill Switch, a podcast series brought to you by Access Now, the KeepItOn coalition, co-sponsored by Internews, and produced by Volume. I am your host Felicia Anthonio.

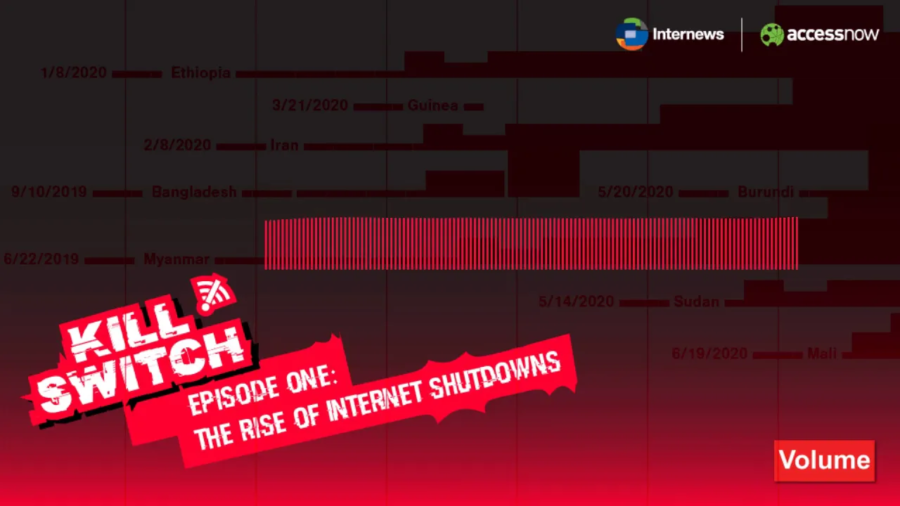

In this six-part series, we want to highlight the troubling rise of a new form of antidemocratic oppression spreading across the world: government-created Internet shutdowns. We will be hearing from journalists, activists, and experts who have been fighting to keep the Internet on, all the way from the high court of Sudan to the rural regions of Pakistan.

This first episode takes a look at the ongoing Internet shutdowns around the world and their impact on human rights. We are launching this podcast on the 27th of July 2020 at the opening of RightsCon, the world’s leading event on human rights in the digital age, which will be hosted entirely online for the first time this year.

As we are recording this first episode, Africa’s second most-populated country, Ethiopia, has been cut off from the Internet for over three weeks. Even though the government recently restored access to broadband connections, there is still no mobile Internet, a source of connection on which most people in the country rely on for Internet access. Berhan Taye, who works as the Global Internet Shutdowns Lead at Access Now with me, has kept her eyes on the shutdown.

Berhan Taye: It’s been almost three weeks since Ethiopia shut down the Internet, and this time around the Internet was shut down because of some violent incidents that happened in Addis and in other places. So a very prominent a very prominent and political and social activist musician was shot and killed in Addis.

Anthonio: It was a rumor saying that an activist, Hachalu Hundessa, who was shot dead on the 9th of June 2019 by an unidentified assailant. This sparked nationwide protests.

Taye: It’s been chaotic since then. So it’s estimated that the government has arrested around 4,900 people, so far. Over 160 people have died but that’s just a number the government has admitted. So we’re yet to see the actual reality on the ground.

Anthonio: Part of our job at Access Now, an international organization that works to defend and extend digital rights of users at such risk globally, is to keep track of shutdowns in India, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sudan, Cameroon, Togo, and dozens of other countries. But it is always difficult to know what exactly is happening during these information blackouts.

Taye: So, whenever a shutdown happens it’s always extremely difficult to find information, you know, to reach out to your family. It’s always very very difficult to find actual information as it happens on the ground. So this time around, when Hachalu was killed it happened at night, and in the morning there were protests across the city. And all of a sudden, almost the whole country went off the grid. So there was literally no traffic coming out of the country and if it was it was through some satellite connections. And for those of us that work in the human rights sector, that work for civil society organizations, and there are also Ethiopians living abroad, it was very difficult to find any information on the ground.

Anthonio: For Berhan, herself an Ethiopian currently living in Nairobi, this most recent shutdown hits close to home.

Taye: So we’ve heard you know, there were gunshots. For instance I’ve heard there were gunshots around my parents’ house. So Icouldn’t reach my parents, I couldn’t find out what was happening. And if you come at it from a civil society and human rights documentation perspective, I think one of the reasons why we don’t know until today the extent of the violence, the extent of the damage, the extent of the injuries and the casualties is actually because the Internet went completely off. In addition to the Internet going completely off, mobile networks were completely affected.

Anthonio: Ethiopia is just the latest country in which the government decided to shut down the Internet. In 2019, Access Now recorded over 213 partial or full Internet shutdowns. Some of these lasted hours, and others lasted months. If you have not heard about a drastic rise of Internet shutdowns around the world, it might be because these shutdowns are so successful in achieving their goals. You could even say that one successful indicator of an Internet shutdown is that nobody is able to talk about it. Here is a Berhan again.

Taye: So basically what an Internet shutdown does is that it intentionally disrupts Internet or electronic communication, with the intent to make them inaccessible or effectively unusable for a specific population within a location, often to exert control over the free flow of information. We came up with this definition as Access Now, as the KeepItOn coalition, and with folks that have been monitoring and documenting censorship and Internet shutdowns.

Anthonio: Governments around the world are switching off the Internet whenever they want. This is due to the rise of a new Information Age mechanism of antidemocratic oppression, the kill switch.

Taye: So if you look at how a shutdown is done or what it constitutes—so for instance you can shut down the Internet just for a specific region, for a specific neighborhoods, or for a specific city, or a whole block of a city. Or you can completely shut it off for the whole country. In Myanmar, in Ethiopia, in Bangladesh, this happens a lot. You target specific locations and the rest of the country will have Internet, but that specific location won’t have it.

Anthonio: Full Internet shutdowns are often the result of a series of increasingly strict control.

Taye: You know, you don’t want the whole country to go off the grid, but you don’t want people to have access to certain web sites, or you want to slow down the Internet connection so that people will be able to read text—you know, they’ll be able to get onto web sites. But they won’t be able to upload pictures, videos, or livestream. So this is what we normally call a slowdown or a throttling. And if there’s a protest happening and you’re livestreaming excessive use of violence by law enforcement agencies…and then the governments in most contexts will just turn off 4G and 3G data.

Anthonio: What that means is that you are left with a 2G network connection. This is an Internet speed of less than 500 kilobytes per second.

Taye: When you’re scrolling on Facebook, for instance, you’ll be able to see text but you won’t be able to see image. You won’t be able to upload videos. This is done deliberately, especially in contexts where there’s protest happening. Governments want to control the information you share, and especially video and audio and images are what they’re trying to control.

Anthonio: And then, you also get governments that decide to simply block social media completely.

Taye: We always say there’s a difference between for instance blocking the New York Times web site in comparison to Facebook for instance, because the fact that Facebook and other social media platforms, even though they’re problematic for many other reasons, they still enable that two-way communication between users, which is really really important, right. Like so at a protest, I can be able to organize using Facebook to say, “Come. Let’s all meet at the square and this is the thing that we’re going to be protesting about today.”

Anthonio: This becomes a good indicator of where and when the next full Internet shutdown will occur.

Taye: Especially in a protest and election contexts they block social media, and then when people use VPNs to circumvent that social media blocking, then they resort to shutting off the whole Internet.

Anthonio: Berhan and I lead the KeepItOn campaign at Access Now, which unites over 220 organizations across the world, working to end Internet shutdowns globally.

Taye: Our sole mandate is to fight against Internet shutdowns and to stop Internet shutdowns. As we do that work of course, we provide technical assistance to circumvent some forms of shutdowns, you know, social media blocking. We document and identify incidents of Internet shutdowns around the world. And we also document what happens when the Internet goes off. We’re seeing more and more that Internet shutdowns and human rights violations go hand in hand. So our main task is to make sure that Internet shutdowns don’t happen. But if they do happen, we can say we’ve been there, we’ve documented this, this is what we’ve seen, this is what has happened when the Internet goes off.

Anthonio: The stories that we find, told to us by people living in affected areas, often show the human cost of a shutdown. One of the stories comes from that 2019 Internet shutdown in Sudan.

Taye: So the government had shut down the Internet at some point. They shut down Facebook. So we were trying to document stories. So this man goes to us and said, “You know, when Facebook was was around,” he was like, “it was much much easier to find dead bodies of families that we’ve lost.” And it’s so gruesome that he says, “The morgues, because they were flooded with so many bodies that they would take pictures of the bodies and post it on Facebook and ask people, ‘Is this your brother? Is this your sister? Is this your mother? If you know this person their body is at this hospital.’ ”

So he’s telling us that you know, because Facebook is blocked and because the morgues can’t do that he can’t find his brother. He can’t find his friends. That was one of the stories where I was like you know, it’s not about even human rights violations anymore. It’s about being able to bury your loved ones. I think that story really stuck with me.

Anthonio: The trend we are seeing is worrying. Shutdowns seem to be spreading across the globe. And the governments seem to grow increasingly comfortable with throwing the kill switch.

Taye: You know, 2020 we thought was going to be different because of COVID. Governments you know, they might want their citizens to access free information but that has not been the case. Governments like Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, Indonesia, Ethiopia, Togo, Burundi, Mali…[recording of Taye is faded out]

Anthonio: The list goes on, and on, and on.

India, the world’s most populous democracy, is also one of the major perpetrators of Internet shutdowns globally. With a staggering 121 recorded incidents of Internet shutdowns in 2019 alone, the Indian government has a heavy hand on the kill switch.

Mishi Choudhary: My name is Mishi Choudhary. I am a lawyer with law practice in New York and India. I am also the founder of Software Freedom Law Center India, which is an organization which works on the intersection of law, technology, and policy.

Anthonio: The organization brings together lawyers, journalists, policymakers, and technologists in order to make future tech policies for India.

Choudhary: We are also the organization which found the Internet Shutdowns project, which was the first of its kind in the world to track Internet shutdowns in India. It’s called internetshutdowns.in, and it is a map-based tracker, and it keeps track of state-declared Internet shutdowns.

Anthonio: India has over a billion people, and half of those are Internet users. Mishi’s organization has been keeping track of Internet shutdowns since 2012.

Choudhary: From 2012 up to July 2020, we have recorded a total of 412 Internet shutdowns so far. And as part of this number of 412, right, from 2012 up to now, we are only recording complete shutdowns.

Anthonio: Though India is a huge country, the shutdowns are centered on certain hotspots.

Choudhary: Several of them are concentrated in Jammu and Kashmir, which used to be a state until last year but now has been converted into a union territory directly under the central government. And therefore whenever there is a shutdown, obviously life is disrupted, economies brought to a standstill, education suffers, health suffers.

Anthonio: When shutdowns are happening in certain areas, it isn’t always easy to know exactly when they’ve even happened.

Choudhary: In fact, when our organization started documenting Internet shutdowns, we were only documenting some web sites which had been blocked. And then we started getting information that in certain areas there was just no Internet at all, a complete blackout. So that means that the authorities were not even making an official announcement and putting the public on notice that there would be an Internet shutdown.

Anthonio: When they started this project, Mishi also started litigation in order to enforce the respect of digital rights. After all, Mishi’s an experienced lawyer, with a mission to accomplish.

Choudhary: The first case was filed in 2015. Then there was another case in 2018. ’19 there have been several petitions. And in the Supreme Court of India, there was a major petition challenging the long, 213 days-long Internet shutdown in the state of Jammu and Kashmir also.

Anthonio: In August 2017, the executive branch launched new rules which spelled out conditions under which a shutdown can be launched.

Choudhary: In the last edition now, the Supreme Court held that the public needs to be informed. There cannot be an indefinite Internet shutdown. And all orders that order Internet shutdowns also have to be made public so that people know what the reason is, why an Internet shutdown is being ordered, and if they want to they can also challenge it in courts. So, some improvement has been made, but India continues to use this as a mechanism in order to sometimes curb law and order situations, sometimes prevent cheating in examinations, and at other times for communal protests, communal riots… And in the recent past we’ve also seen that wherever there were protests, that also in those regions Internet was shut down.

Anthonio: The frequency of shutdowns in India seems to suggest that it has become a part of daily life in the democratic Indian society.

Choudhary: What we do is we collect videos, text messages—because of of course there’s no Internet—so people make videos later on, or if they move to another part of the country they send us videos. During the shutdowns they send us text messages. If they can somehow get intermittent access, they send us some clips, etc. of how their life is being impacted.

Anthonio: India has become a country where the state has a very strong control over Internet connectivity and digital rights in general.

Choudhary: Some things that have stayed with us are especially during the pandemic, when we all have now come to depend on Internet for education, for business, for…going to work, as one says. For shopping, for everything. It has been really really heart-wrenching to see that people in parts of the country where Internet is not available, or is available at much much slower speeds, such as 2G speeds, what they go through.

Some of the stories which stayed with us was children not being able to apply for university admissions because all the applications to the university were available only online. And because there was no Internet, they could not apply in time to go to the universities.

And one very very interesting thing that happened was that recently, because we had been challenging and bringing the plight of the people in Kashmir about Internet shutdowns to the courts and the courts had not really given the desired relief to those people, the Chief Justice of the Jammu and Kashmir High Court, she herself was complaining that she could not do her work and appear on discussions online because Internet was unreliable in their area. And that really sent the point home.

Anthonio: While India holds the record for the most shutdowns in the region, across the border in Pakistan the government is setting another alarming precedent. In Wāṇa, South Waziristan Agency, there was an Internet shutdown that lasted 3,411 days. The kill switch simply stayed off.

Hija Kamran: Hi, my name is Hija Kamran, and I’m currently working at Media Matters for Democracy as a digital rights lead, and also managing the Digital Rights Monitor, which is Pakistan’s first digital rights-focused news web site.

Anthonio: The Digital Rights Monitor, produced by Media Matters for Democracy, is the first publication of its kind in Pakistan.

Kamran: We basically report on digital rights-related issues in Pakistan and also some major developments from the global community as well. So we kind of fill that void of information that exists around digital rights in Pakistan.

Anthonio: For a long time, digital rights have not been part of any kind of human rights discussion in Pakistan.

Kamran: People have a lot of other issues that they deal with, and this is one of the arguments that we have to counter in all of our conversations that we have with regular Internet users as well. When you talk about digital rights, the word rights doesn’t sit well with them? Because people do not have access to basic necessities like you know, food, shelter, clothing. They need to first have access to those rights and then we can venture into digital rights.

Anthonio: Hija explains that part of their work is to make it clear to people that digital rights and access to the Internet, and to information, have become increasingly interconnected to our most basic human rights.

Kamran: Essentially, Internet provides a power for people to voice their concerns. For example if you do not have access to something—there is a lot of electricity issues in Pakistan—a lot of people turn to Twitter or Facebook to connect with their utility service provider. And they could voice their concern and they share their concern but they do not have power [indistinct], so we need access to it now. So it’s basically a tool to demand access to these fundamental rights that most of the people do not have in Pakistan.

Anthonio: The reason why the fight for digital rights is so important in Pakistan is also closely connected to the country’s history of Internet shutdowns.

Kamran: I cannot point out the exact year, exact moment it actually began, but the earliest memory that I have is from 2007 when the former prime minister of Pakistan Benazir Bhutto was assassinated in Karachi. So I remember when the assassination happened, naturally there was a lot of chaos in the city and also across the country as well. The first line of action that the authorities took was to suspend mobile networks.

Anthonio: Since then, the kill switch has become just another tool for the government to use to run the country.

Kamran: You see the trend happening, extending from that point onward. You see how even in villages…you know, events like Ashura, religious events like you know, birth of the prophet Muhammad. And also national events like Independence Day or the Defence Day, these Internet shutdowns have been very frequent. That they actually do is basically just extend…as everybody knows, just extend chaos and confusion among people.

There was this instance in 2017 where an Islamic extremist group in Pakistan started this riot across the country, sort of just to demand authorities to accept whatever they were demanding from them. And the government basically suspended mobile networks, suspended the mainstream media coverage in Pakistan. And to think that while there is a riot happening outside of your door you do not know what the situation is and whether it’s safe to step outside your house and you know, just run for an emergency…[recording of Kamran is faded out]

Anthonio: But unlike shutdowns that only last while there are riots or protests, there are parts of Pakistan where the Internet just stays switched off.

Kamran: For example in 2017 I remember when I first reported on the Internet shutdown that has been going on since 2016. The issue that came forward was that journalists cannot report any breaking news because they have to travel long distances.

Anthonio: The reason the government gives for their continued shutdown is that they want to ensure security in the region during ongoing conflicts with terrorists.

Kamran: There is this instance from 2017 where there was a bomb blast in an area of Parachinar, which is a city in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. People in the rest of the country did not know for hours or for days that a bomb blast of high magnitude has happened in a city, because there was no media in that area to report on it. So you know, lives are lost, but the information is not being reported, people cannot voice their concerns, people cannot demand security, people cannot demand their fundamental rights that are protected under the constitution.

Anthonio: As a shutdown such as this gets longer and longer, the effects are compounded. It is not only about information getting out, but also about information being able to get in.

Kamran: I was talking to a journalist in the region which is now the former FATA and now part of the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. I was talking to the journalist and he told me that there are people who do not even know that there is something called coronavirus because people do not have information about the seriousness of the issue. They are roaming around the streets, they are going to bazaars, they are going to market, they are opening their shops and doing all the things that they usually do. And then you know, access to healthcare is also very shaky in that area. Hospitals are almost nonexistent, and again they have to travel long distances to access healthcare as well. So, not having access to the Internet and the information that is available on it is resulting in issues of healthcare and issues of access to education as well.

Anthonio: Access to information is not only essential for securing your human rights, it’s also essential for knowing that you have rights to begin with.

Kamran: They do not want the citizens, the residents of the region to have the information that is essential for them to stand for their rights because these are the people who have been systematically oppressed. So they believe that it is also the government’s way to not have us empowered, not have the citizens have the information around their rights, because that would mean we would say truth to power or we would demand our rights, so the government basically do not want us to do that also.

Anthonio: On the ground, students who are fed up with the shutdowns are also mobilizing for change.

Kamran: So I think there is just a huge movement going on around access to Internet that is being basically started by the students in all of these regions that do not have Internet access right now. Because this is not a new issue, not in the region, not in the country. This is not a new issue. A few people actually have been talking about it for a very long time, for years in fact since it has been going on. But because it is now affecting people who have voice and who are speaking up because they have some kind of Internet access or they are located in regions where they do have Internet access, they are now speaking up and they’re more vocal about it. So it’s now being reported in mainstream media. But for the longest time because of security reasons nobody would want to watch a report on these issues because that would mean challenging the authority’s decision and that is not a norm in Pakistan. That is not what we see people doing a lot in Pakistan.

Anthonio: The government in Myanmar is slowly moving in the direction of Pakistan. The mobile Internet shutdown which began on June 21, 2019 recently has reached its one-year anniversary. It’s an anniversary that many feel is not worth celebrating.

Oliver Spencer: On the 20th of June 2019, the government issued a directive under the telecommunications law ordering all mobile data access to be cut for nine townships across the western part of the country, which has got a lot of conflict going on at the moment.

Anthonio: Oliver Spencer is a legal advisor to Free Expression Myanmar, an organization that has been fighting for digital rights and access to the Internet in Myanmar for years now.

Spencer: The area which the shutdown has applied to has grown and shrunk over the period since last year. And it now covers about 1.4 million people. So that’s 1.4 million people that don’t have any access to mobile data. And this is in a country where almost all Internet access is through mobile data.

Anthonio: The government of Myanmar has been careful in its messaging. Despite what might be happening in the country itself, they want to make sure that the international community perceives it as acting justly.

Spencer: So our work is mostly around advocacy with government, businesses, and other stakeholders to highlight what’s happening or why the shutdown is a poor decision that will not achieve their security goals but instead threaten many of the rights and the development of the people that are involved.

The main issue FEM faces is that the government claims it’s democratizing, but is using all of the old tools of the dictatorship. They in effect are trying to justify the means by the ends. So all we’ve got to rely on are the official statements— I’m sorry, officials making statements, answering very brief media questions. So you know, you’re talking about journalists asking a question and receiving a sort of one-sentence answer.

What they’ve said in these brief statements are that it’s relating to disturbance of peace, coordinated illegal activities, national security. We’ve heard also about so-called public interest, and also hate speech.

Anthonio: The government’s narrative becomes the only narrative. And the less information they give out, the less accountability they have.

Spencer: These justifications are complicated, from what we’ve seen. For a start the conflict has not decreased. Many CSOs and observers of the conflict may even have said it’s increased over the period. Security certainly hasn’t increased within that area. So it’s a very broad, very vague shutdown that in effect just severely restricts 1.4 million people on a very vague and imprecise basis, with no test of the impact of the shutdown, no test of the balancing act between national security and access to the Internet.

Anthonio: What we’ve seen happen again and again is that once a government starts experimenting with Internet shutdowns, they grow more and more confidence in using the kill switch and other tools of information control and censorship.

Spencer: Since the shutdown started in June 2019, earlier this year we also saw an escalation because the government then started blocking—or, sorry, the government then issued directives ordering telecoms companies to block web sites. And these web sites included both news web sites and also CSO’s web sites from within this area. So in effect they have escalated their crackdown on the communications flows. Because now not only is the Internet shut down for this entire population, but the one or two media outlets which actually had access within the area and were publishing stories to the rest of the country and the world about what was happening there, they also are not accessible now to anyone using the mobile Internet. It seems like we’re now in a period of escalation. I’m just concerned about what will be censored online next.

Anthonio: The final observation from Oliver perhaps ties the stories in this episode together best.

Spencer: You’ve got countries like India which have spent the last five years doing multiple short-term shutdowns in different areas across the country. And I think what’s clear to [indistinct] is that the other countries in the region are actually learning from this. They’re learning how to do it. They’re learning if they do it there’s very little repercussion upon them. And so I think we’re going to see an increase across the region because they all learn from each other about how powerful this is as a tool.

Anthonio: When a spokesperson of the President’s Office of Myanmar justified their shutdown by saying that other countries in the world have similar practices for security concerns, it was perhaps a reference to the actions of governments such as that of Pakistan and Ethiopia. But a statement is also a dark echo of what NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden said a few years earlier in 2017 during the Internet shutdown in Cameroon. I quote, This is the future of repression. If we do not fight it there, it will happen here. #KeepItOn

In the next episode, we find out what happens when activists take their governments and telecommunication companies complicit in these shutdowns to court.

For more information about how to support the KeepItOn coalition and our work, visit our web site, www.accessnow.org. This podcast was produced by Access Now and Volume, with funding support from Internews. Our music is by Oman Morí. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and share as widely as possible to help the fight against Internet shutdowns, and to Keep It On. I am your host Felicia Anthonio, and you have been listening to Kill Switch. Goodbye, and remember to Keep It On.