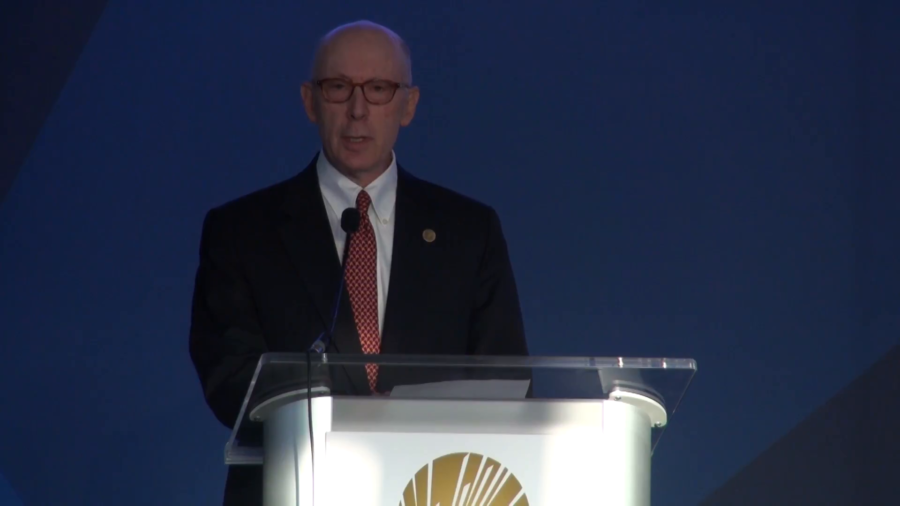

Ira Fuchs: Thank you very much. I’m absolutely delighted to be here on this, the twenty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the Internet Society. This month also marks the thirty-sixth anniversary of the founding of BITNET. So, thank you to the Internet Society for remembering a bit of Internet history that might otherwise be overlooked. Heretofore the most notable recognition given to BITNET was when the Oxford English Dictionary, the OED decided that BITNET was a word and added it to the dictionary.

People have asked me, “Why did you create BITNET?” Well, the truthful answer is I was envious of ARPANET users. They had access to the most exciting technology at the time. But ARPANET, as you know, was only available to a relatively small group of developers and researchers. And we didn’t know if it would ever be made available to others. I wanted to find a way to provide at least some of the core ARPANET services—email, file transfer, and interactive messaging—to a much larger group that included faculty and students, in all disciplines, at every college and university in the world.

I needed a path, though, that didn’t require a lot of technology—new technology—to be developed. And I decided not to seek government support. So I modeled the network after VNET, IBM’s then-corporate network, that was the largest global network in the world at the time. They had over twelve hundred nodes throughout the planet. And IBM’s global network corporate network utilized IBM’s RSCS networking software.

And I asked my colleague, Grey Freemen at Yale, if he would be willing to connect Yale to City University of New York where I was, as a start. And he liked the idea. So we connected our institutions with 9,600-baud leased lines, and we named the network BITNET—originally “Because It’s There,” and later “Because It’s Time” Network.

And then I invited thirty-four colleges and universities to join our fledgling enterprise. Now, since many of those schools, maybe even all of them, were using IBM mainframes, it meant they already had what was needed to join. And as a result, it grew very quickly. Within a year or so, we were able to show success in the United States. Which led to IBM offering to support a European backbone by connecting City University of New York directly to Rome, and funding the inter-country links leading to the birth of EARN, the European Academic Research Network.

With IBM’s help, and the work of many people in the countries served, we were able to connect scholars in most of Western Europe, Japan, Taiwan, Israel, South America. And we were the first to connect Russia. And at its peak, BITNET had forty-nine countries connected.

BITNET had other firsts. BITNET had the first extensive and highly-successful listserve service. Unfortunately BITNET also had the first widely-disruptive worm, the “Christmas Tree EXEC,” which was launched by a German student in 1987 and which managed within a very short period, minutes, to bring down all of BITNET, EARN, and the IBM corporate network. [laughter]

BITNET’s main legacy was that it gave schools, I think, the initial motivation to wire their campuses and begin using electronic communication, to share research and ideas with their colleagues throughout the world. And it created, I think, a set of expectations regarding openness and accessibility that continue to this day. In effect, BITNET ended up being an almost decade-long warm-up act for the Internet, a fact that would probably be forgotten were it not for the Internet Society. So thank you very much.