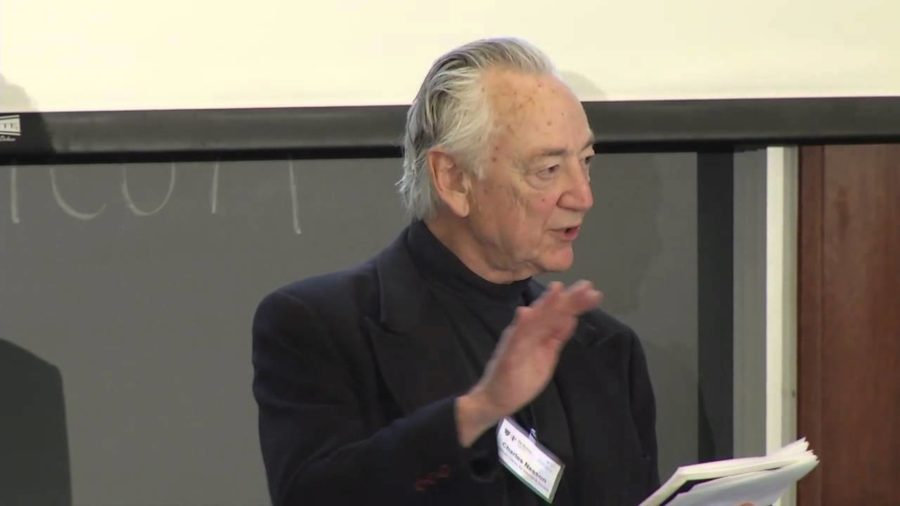

Susan Crawford: Charlie, the William Weld Professor here at the Harvard Law School and a cofounder of the Berkman Center. And also of course the founder of the Poker Society internationally, teaches most importantly, for this context, evidence, where he really thinks about information that’s necessary to persuade. Information in context. How we deal with all these human biases and limitations of our corporeal selves, and try to assess a societal version of the truth collectively. So Charlie, take us away towards lunch.

Charles Nesson: Jonathan Zittrain and I started the Berkman Center as a means of claiming and reclaiming, building, an open cyber space that would somehow integrate with all our lives in ways that would make life better.

So, truthiness is a rhetorical poker game that the net lets people play. There is a truth that is self-evident. That all men are created equal. This moral truth defines Americans as a people. Built on this moral foundation, our founders wrote our Constitution in our name.

I am a teacher of evidence and the American jury. These are two classes. Both are about the American means for determining legal truth. In evidence, we study what legal truth is and how the law lord makes it, using jury trial. And then how the law lord plays it in the rhetorical poker game of truthiness that’s played with the other lords of truth who vie for mindspace and credibility. The journalism lord, the science lord, the lord of religion, to name just a few of the others.

[Nesson’s slides are not shown in this recording, but the following paragraph refers to the Necker cube illusion]

I’m not sure that this is…can you see this cube two ways? Can you all see it two ways? Is there anyone who cannot see it two ways? Is there anyone who can see it both ways at the same time? No. You can’t. Because to see it in a different way you must change your point of view. So this becomes a metaphor for truth.

In the American jury class, we study the place of the American jury in American life. As conceived by our founders, the jury and its truthiness lay at the foundation of the American republic, and at the core of American civic life.

In the class we study the decline of the jury under the pressures of American corporatism and American racism. As you look at the Necker cube and contemplate the two-sidedness of truth, you can ask yourself is there a truth we share?

Well I believe there is a truth we share. I think it’s our sense of justice. I think of the great Paul Newman depiction in The Verdict, his closing argument when he speaks to the jury and says, “You are the law. I believe there is justice in our hearts.” So the truth, the verdict. Vera dictos, speak the truth. That’s what juries are told to do.

This is Bill Stuntz. Bill taught criminal justice here for the last part of his career. Started the University of Virginia. At the age of 49 he learned that he had colon cancer. And he set about then writing the book that is the statement of his life, called The Collapse of American Criminal Justice. It’s a book I recommend to all of you. This is the honest statement of a man who was archly conservative in his way. An evangelical Christian. Rock-ribbed Republican. But a book in which he tells us what he’d learned, and it’s in some way quite surprising.

His thesis focuses on what you might call the romance of American justice with proceduralism. And it’s disconnection from the feeling of justice. The extent to which law developed through the Warren period and after. The idea that to defend freedom we do it with procedure. But somehow looking at the procedures in a way that at the end of the day make us blind to the result that comes out and is justified at the other end. So that our prisons are bursting with discrimination. The system that used to be based with a jury at its core now works almost entirely in terms of prosecutorial discretion. So this is a passionate book.

I want to introduce you to a case and to an idea.

…argument next in case 10–1320, Blueford versus Arkansas.

[clip of audio]

What is that? That’s the audio recording of the opening of a case that was argued in the Supreme Court of the United States a week ago Wednesday. All of the Supreme Court cases’ arguments are recorded. And the opportunity to be in the environment of the argument with this kind of life is remarkable.

So this was Blueford v. Arkansas. The issue before the Supreme Court a question of double jeopardy. And guy’s prosecuted for first degree murder, with manslaughter a lesser included offense. The jury is instructed to consider the first degree murder charge first. And only if they all vote to acquit to move on down to the consideration of the manslaughter charge.

They retire. They consider the capital offense. They voted unanimously to acquit. They move on down to the manslaughter charge. They can’t agree. They hang. They come back in. The judge sends them out to reconsider again. They come back in. “We’re hung.” A mistrial is declared.

The issue is the prosecutor now reprosecutes the defendant and includes in the prosecution first degree murder. And the defendant says, “I was put in jeopardy before a jury of my peers already once. And they acquitted me.” And the issue before the Supreme Court is exactly this issue that Stuntz is focused on. Procedurally, there is no final verdict. In justice, this man has been put in trial for his life before twelve of his peers and they voted to acquit.

Our champion in this fight. You will recognize I hope Elana Kagan.

Elana Kagan: If you look at what the judge said, what the prosecutor said, what the defense counsel said and then what the jury said, it’s clear that they all thought that they had to unanimously agree on something before they could go to the next crime. And again, there’s no suggestion in what anybody said that they could go back up.

Antonin Scalia: Is there any suggestion that they couldn’t go back up?

[unknown:] That is extraordinarily important.

Elana Kagan: And isn’t it usually assumed that the jury is not finished until it’s finished?

Just a clip, but you get it. It’s Scalia against Kagan. It’s substance against procedure. And this is a fight that we will see in many forms, as the wisdom of Bill Stuntz penetrates further and further into our judicial thought.

With the net, we have the potential to break through to truth of “We the People.” The truth we look to in ourselves and we feel as fairness.

So, there was at one point earlier in my career a play with television in which I moderated with Fred Friendly as producer a series called The Constitution: That Delicate Balance. Fred Friendly I considered to be a mentor and a person who stood in back of us as we had the idea of the Berkman Center. It was initially an idea that had public education very much in its mind.

I believe that we are now at a point where we can reach for those aspirations of public education. And when I say public education I mean it as public civic education. Education about what it means, what it is, to be a citizen. What it is to participate. What it is to actually be part of building a civic society and constructing it with your membership.

I taught my class yesterday—I’m about to go to the second class. Yesterday my students watched 12 Angry Men. Marvelous. And they watched it in the context of thinking about the jury room as a rhetorical poker environment, where the idea is to pay attention to the techniques by which one juror bullies another. And to the techniques by which the bullying is overcome. It’s an opportunity I’m hoping to carry forward what I see as the wisdom of Lady Gaga on the one hand; the hook that she represents into the sensibility of, to me, a world. And the brilliance of John Palfrey, whom I believe walks on water. I speak specifically of the Digital Public Library of America and the potential that I feel in it to treat library as community space. As place where education takes place. And for me that has to do with a combination, an aspiration, to teach law and poker through the net. And to have it be a participatory event in which, God bless them, people come to libraries and play.

I’m now the principal investigator of a Berkman project called Mindsport Research Project. It’s a conceptualization of strategic games as something as important for kids to engage in as physical sport. And it starts with Connect Four, and checkers, and chess and bridge, and poker. And the idea of imagining cyberspace not as just a virtual space but as an integration of the virtual and the real. The online environment that would support gatherings and community environments, where people play the games face to face. That they learn and enjoy to play online. And to use that as the core of an intellectual spine to teach the way poker in the real world actually works. So, that’s my inflection point. Thank you all very much. Please have lunch.

Further Reference

Truthiness in Digital Media event site