Kevin Bankston: And now I’m gonna take the opportunity to introduce our next solo speaker, Dr. Kanta Dihal, who is the post-doctoral research associate on the AI Narratives project, one of the project leads on the Global AI Narratives project, and the project development lead on the Decolonizing AI project, all of which are at the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence at Cambridge University. Across those projects, she explores how fictional and non-fictional stories shape the development and public understanding of AI, including exploring the range of hopes and fears about AI that are reflected in our stories about AI. Which is what she’s going to talk about today. So Kanta if you could please come up?

Kanta Dihal: Thank you Kevin. So this is work that I’ve been doing since around 2017 with my coauthor Stephen Cavef. We came up with the idea to write a short paper categorizing…trying to make some sense of those many narratives that we have around artificial intelligence and see if we could divide them up into different hopes and different fears. And two years later, we’ve looked at 360 books, films, TV series, and other narratives, in English, from the 20th and 21st centuries. So that’s both a caveat but also an explanation of the scope of our research. We found that many works to look at just within these parameters.

And that work was inspired by the fact that as you just heard on the panel, that prospect of sharing our lives with intelligent machines somehow provokes people to imaginative extremes. So thinking about them seems to make people either wildly optimistic or melodramatically pessimistic. And the optimists believe that AI will solve many if not all of our society’s problems. So you might have heard of the London-based AI company DeepMind, who created AlphaGo, the Go-playing AI system. And they’ve sometimes use the slogan “solve intelligence, and then use that to solve everything else.”

But then there’s the pessimists, who fear that AI in its many forms will inevitably bring about humanity’s downfall. And that’s a theme that’s very frequently picked up by the media. So we were with our center involved with a report on AI by the UK’s Parliament. And when that report was published, a UK tabloid called The Sun covered that with the headline “Lies of the Machines: Boffins (that’s a British word used to describe academics) urged to prevent fibbing robots from staging Terminator-style apocalypse.”

And those stories matter. Those stories influence the development of the technology itself. They influence public fears and expectations. And, they can influence policymakers. So our research aims to explain the structure of our stories around AI and why they have such a grip on our imagination. And we hope that that’s the first step towards having more diverse and constructive responses to the prospects of intelligent machines.

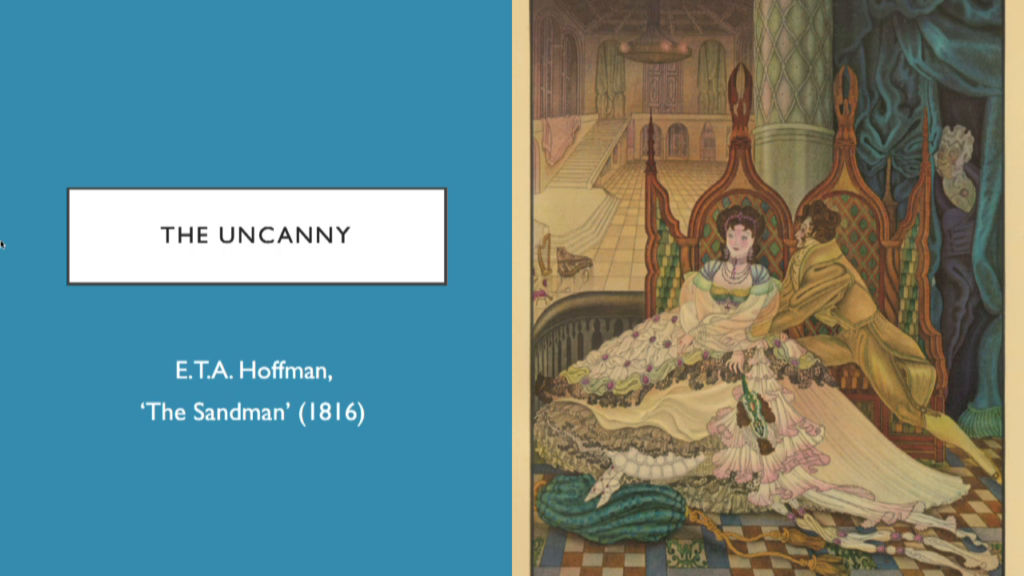

So, why is it that the idea of intelligent machines and especially human-like artificial intelligence fascinates people so much? And for so long. I mean, there have been narratives around intelligent machines for 3,000 years. And serious attempts to explain that fascination started just about a century go with Sigmund Freud, who was one of the first thinkers, actually, to ask why we find such machines so fascinating. And he focuses on how we find them uncanny. And that’s that creepy feeling of seeing an imagined fear become real. And he suggested that one reason for why we find especially human-like AI and androids so unsettling is because they leave us uncertain about just what we are looking at, in terms of reality being not what it seems. In terms of not being sure whether it’s dead or alive. But also that we’re somehow being deceived.

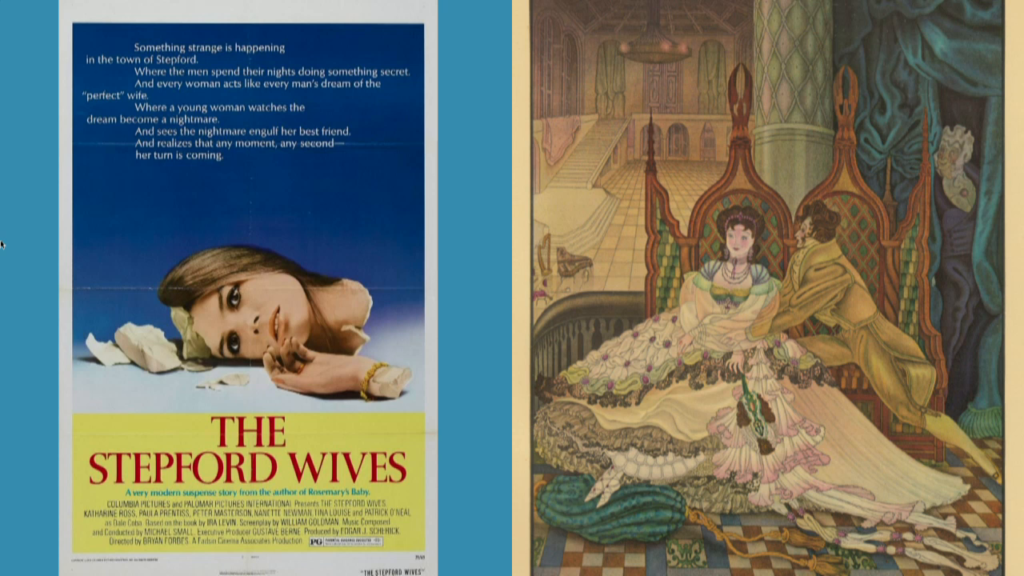

So he discusses a short story from 1816 by ETA Hoffmann called “The Sandman,” in which the protagonist Nathaniel, the man in yellow, is bewitched by the beauty of a woman called Olympia, the one in the very extravagant dress. And after much more wooing, it turns out that Olympia is an automaton. Which makes you wonder how closely this guy was looking at her from so up close? And then when Nathaniel discovers that, it drives him to madness.

And that kind of unease still feeds into contemporary ideas about what artificial intelligence could look like. Like the 1975 film The Stepford Wives, which was remade as a comedy. For those who don’t know it, in that film the menfolk of a small US town replace their much-too-human women with what they consider to be perfect android wives. So they look identical to their original wives but then presumably they bake better muffins.

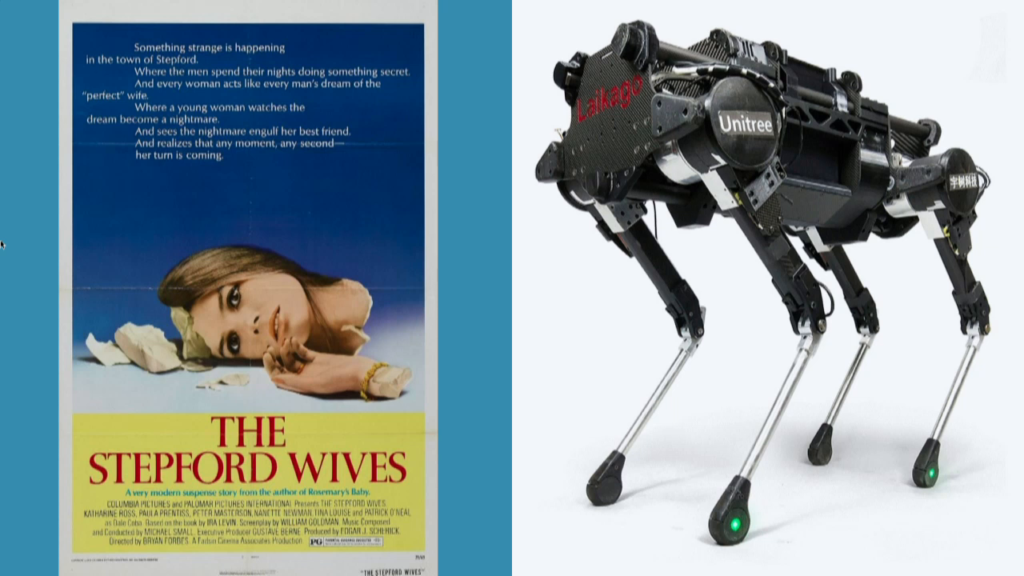

And more recently, historians who have been exploring the fascination with human-like machines have focused on what they call the “liminal quality,” so the boundary-challenging and transgressing quality of those machines. So, we tend to divide up the world very neatly into living things: plants and animals, and non-living things: hammers and nails. But AI and robots seem to be somewhere in between those two. Because like non-living things they are built by humans from inanimate components: metal and plastic. But like living things, especially those intelligent androids that we imagine can speak, think, sometimes walk and so on.

And that category-defying element of AI I think is an important part of why we find them fascinating. If you’ve seen any of the famous YouTube videos of Boston Dynamics and their four-legged robots, you’ll understand that they are captivatingly and slightly disturbingly both like and unlike living machines; living creature. But we also think that there’s more to be said about why we find the idea of such machines so provocative.

And the starting point a lot is that AI is a tool. It’s a piece of technology designed to help us achieve our goals. But it’s also supposed to be an intelligent tool. So a tool with attributes that we would normally associate with humans. A tool that’s autonomous. That can think. That has goals. Perhaps even what you’d call a mind.

And that makes it very different to ordinary tools. And that’s what has such huge implications. Because those attributes are what promise to make AI the ultimate tool. The ultimate technology. It’s in a sense not just a tool, but in all the many ways in which AI will be able to be deployed, it’s seen as the master tool. So the DeepMind slogan “solve intelligence then use that to solve everything else.” Whereas the thinking power of humans is limited by our cranial capacity, AI does seem potentially limitless and promises to work out solutions to all our problems. So it represents the apotheosis of the technological dream. The dream that we’ve been having for technology ever since someone clever rubbed some sticks together. That we can use tools to create a better world, a paradise on Earth. So that’s the source of our extravagant hopes.

But at the same, there’s the idea of creating tools with minds of their own that creates, to our minds, inherent instabilities. Because a tool with goals could have goals that misalign with ours. A smart machine could outsmart us. A machine with autonomy could choose to disobey. And that instability is the source of extravagant fear.

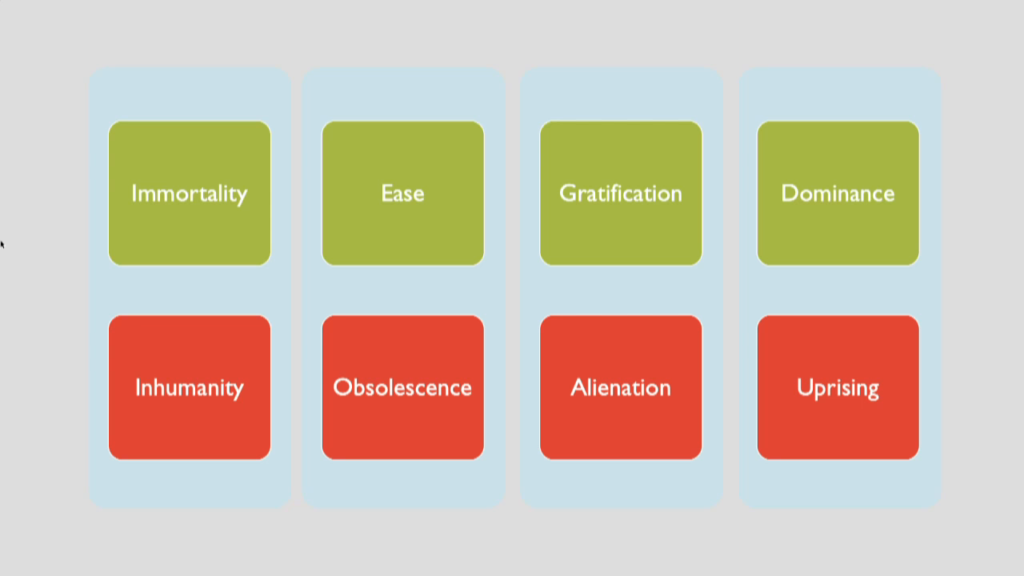

So we argue in our research that those hopes and fears go together. We’ve analyzed works that include both fiction and what we call speculative non-fiction; so non-fiction that explores the future. And on the basis of that we identified four dichotomies that structure our affective responses to intelligent machines so that each consists of a hope and a corresponding fear.

Eternal life possible through AI: Rich and famous will SWITCH BODIES like Altered Carbon: A LEADING artificial intelligence expert has revealed how robotics will allow some humans to live forever —Daily Star, 3 February 2018

So first let’s look at the hopes in detail. The first one concerns life. The pursuit of health and longevity is humans’ most basic drive. I mean, it is the precondition for almost anything else that you might want to do. So consequently humans have always used technology to try to extend our lives. So it’s no surprise that for AI the hope is that it will do that in the way of giving us better diagnoses, personalized medicine, and so on. And the most ardent advocates of AI’s potential in this field suggest that it would make us somehow entirely immune to aging and disease and to allow us to become what’s sometimes called “medically immortal.” But that’s not real immortality, because it still relies on having this human body which is in all kinds of ways messy and unreliable, and can be hit by cars. So, many advocates go even further, suggesting that we could actually transcended the body altogether and upload our minds into cyberspace.

Robot Servants Less than 10 Years Away, Daily Telegraph Australia, 23 October 2017

Now the second hope concerns time. So assuming we manage to stay alive for as long as we wish, then we hope to be able to use all that time as we wish. So that’s the dream of AI freeing us from the burden of work that we don’t want to do. So, no more mind-numbing days filling in Excel spreadsheets behind your desks, because the AI will do all th at. And we’ll live in smart homes that will do all the laundry folding for us, and we’ll be lords and ladies of those AI manors. And AI offers us such a life of luxury and ease, and potentially could do so without having the very complex social and psychological pressures of having human servants—so humans that you use to do the dirty work for you.

Would you MARRY a robot? Artificial intelligence will allow people to find lasting love with machines, expert claims, Daily Mail, 12 February 2016

The third hope concerns desire. Once we have time, we want to fill it with all the things that bring us pleasure. So just as AI promises to automate work, it promises to automate and uncomplicate the fulfillment of every desire. It could be the perfect friend, always there, always ready to listen, never demanding anything in return. And in imaginings of AI there’s loads of examples, starting with Isaac Asimov’s very first robot story “Robbie” about a robot nanny, to the operating system Samantha in the film Her. And of course many hope that intelligent androids will be the perfect lovers, as we saw in for instance Westworld, until that went wrong. [audience laughs]

Artificial intelligence decodes Islamic State strategy, BBC News, 6, August 2013

And finally the fourth hope concerns power. So once humans have created that paradise in which we have life and time and all our desires are filled, we’d want to protect that. And I might add that humans have a habit not just of fighting to protect their favored way of life but also to force it on others. And in an AI context, the Culture novels of Iain M. Banks present such a view. So stories of what we call intelligent autonomous weapons are ancient. They go back at least to ancient Greece, to the bronze giant Talos, who defended the island of Crete from pirates and invaders by throwing boulders at them. And you have stories of bronze knights guarding secret passageways all the way through the Middle Ages. And then in modern times of course, much of the funding for AI research has come directly from the military. So as the master technology, AI is also potentially the ultimate weapon.

So that’s four utopian visions that those hopes reflect, but they are inherently unstable. The conditions for each hope to be fulfilled bring about that potential for that utopia to collapse into a dystopia. And one factor in particular is key to that balance between hope and fear and where it tips over. And that is control. So the extent to which humans are in control of the AI, rather than AI being in control of the humans, determines whether we consider a future prospect utopian or dystopian.

Humans could achieve ‘electronic immortality’ by 2050 and attend our own FUNERALS in a new body, futurist claims (but he warns our minds could be ‘enslaved’ if we aren’t careful), Daily Mail, 24 July 2018

So on the dystopian side, on the subject of life, while people to achieve immortality its flipside is losing our humanity in the process. Because what are we willing to sacrifice in order to live forever? Our memories, as the panel just discussed? Our emotions, our physical form, our individuality and embodiment? So this is a Ship of Theseus question. If you replace all your bits with metal prostheses, is the resulting immortal being still you? And how much humanity will be left when you turn yourself into pure data and upload yourself to one of those server farms in Arizona?

Robots are the ultimate job stealers. Blame them, not immigrants, The Guardian, 14 February 2018

And our hopes for having more time can turn into fears of obsolescence when we lose control of the amount of leisure time that we have. So at the same time as we dream of being free from work, there’s this terrifying idea of being put out of work, because of course work doesn’t only provide an income but also a role in society, status, standing, a feeling of accomplishment, pride, and purpose. So, a UK paper had the headline last year “Robots are the ultimate job stealers. Blame them, not immigrants.” I’m not sure if that’s so helpful. [audience laughs]

Of course, as technology advances, most most of opponents to this idea say well eventually there will be new jobs created because of AI. But of course, we wonder… It’s quite understandable that people would worry if AI continue to be developed that get better at more and more things, what will be left for us to do?

MACHINE MISTRESS Brit women risk being REPLACED for sex by robots if MPs don’t act, campaigners warn, The Sun, 30 July 2018

And our hopes with regard to desire can tip into the fear that we on the one hand to might bring something unnatural or monstrous into our home. So that’s that uncanny valley, the effect that you get nowadays when you see those robots that are supposed to look like humans but they don’t really. But there’s also fears regarding AI being better than humans. So, if we have all our desires fulfilled by AIs, then that means we become redundant to each other. We might not only become obsolete in the workplace but even in our own homes and in our own relationships.

AI to bring ‘mankind to edge of APOCALYPSE’ – with robots a bigger risk than NUKES, Daily Star, 15 July 2018

And finally we can easily imagine how the hope of acquiring dominance turns into its flipside, the fear of being dominated. So first there’s the fear of losing control of AI as a tool—the sorcerer’s apprentice scenario, or the Roomba going wild and hoovering up your hamster. But on another level there is the fear that AIs will acquire minds of their own so that they turn from tools into agents. And that robot rebellion theme is really persistent and reveals that there’s a paradox at the heart of our relationship with intelligent machines. That we want clever tools that can do everything we can and more, including be the perfect soldier. And then for those tools to fulfill our hopes, we give them attributes like intellect and autonomy. And of course it’s not hard to see the tension in the idea of creating beings that are superhuman in capacity and subhuman in their status. So, fears of Skynet show that recognition of the deep paradox in creating powerful independent minds enslaved to us, which is why so many narratives of robot rebellion so closely parallel narratives of slave rebellion. But that’s another piece of research I’m working on.

So, that’s our eight hopes and fears. And last year we decided to look at the role that these eight narratives play in the life of the average British person. So we surveyed over 1,000 people, and the findings of that survey show that the UK population has a markedly negative view of AI. So levels of concern were on average significantly higher than levels of excitement across these narratives. And unfortunately, concern was higher than excitement even for several of the hopeful narratives.

And also we had an open question, “How would you explain AI to a friend?” And in response nearly 10% of people spontaneously offered negative sentiments instead of explaining what AI is. So we titled the paper “Scary Robots,” because that’s literally what someone replied: How would you explain AI to a friend? “Scary robots.”

So dystopian visions seem to be so entrenched that large numbers of people are inclined to see the downsides of AI even when presented with wholly utopian visions. So negotiating the deployment of AI and informing people of what it can and cannot do will have to contend with those entrenched fears that underlie even what seem to look like quite positive stories. Thank you.