Lindsay Blackwell: Hi everybody, my name is Lindsay Blackwell. I’m a PhD candidate at the University of Michigan Social Media Lab, which is in the School of Information. And I am here today to talk to you about HeartMob.

HeartMob is a private online community designed to provide support for people experiencing online harassment. When I talk about online harassment I’m referring to a very broad spectrum of abusive behaviors that are enabled by technology platforms and used to target a user or a group of users. So this can be anything from a flaming or the use of personal insults or inflammatory language, to things like doxing or revealing or broadcasting personal information about someone such as a phone number or address, to things like stalking and impersonation and things of that nature.

So just to keep that in mind, this is not an uncommon experience. We know from Pew that 41% of adult American Internet users have personally experienced online harassment. We also know that nearly two thirds of American adults have witnessed online harassment in their feed. So this is something that’s happening a lot.

Online Harassment, Digital Abuse, and Cyberstalking in America;

Online Violence Against Trans Women Perpetuates Dangerous Cycle

Women, people of color, LGBT people, and young people are significantly more likely to experience online harassment than their counterparts.

And online harassment has serious impacts both on people’s online and offline lives. So this is not just an online problem. People do report changing their online privacy behaviors, perhaps leaving social media sites altogether when they have an experience with harassment. But they also report disruptions of their offline lives, emotional and physical distress, increased privacy concerns, and also distractions from personal lives and work obligations due to the time that’s required, the emotional and physical labor that’s required, to manage harassment when you’re experiencing it. So if you’re being harassed by hundreds of people and you want the platform that that’s happening on to intervene, it’s your responsibility to go through and report all of those comments, which takes a lot of time and a lot of effort.

No one knows that better than the leaders of Hollaback. Hollaback is an advocacy organization dedicated to ending harassment in public spaces, namely street harassment. And because of the nature of the work that the leaders of this organization do, they’ve suffered consistent and severe online harassment. So, they took their collective experience in intersectional feminist practice, bystander intervention, and social movement-building, and they applied that expertise to creating an online space, an online community, for people who are also experiencing online harassment. And they did that with the help of a large group of people who were frequent targets of online harassment themselves. So they really tried to design a community that would serve the needs of the people who are most vulnerable to these types of behaviors.

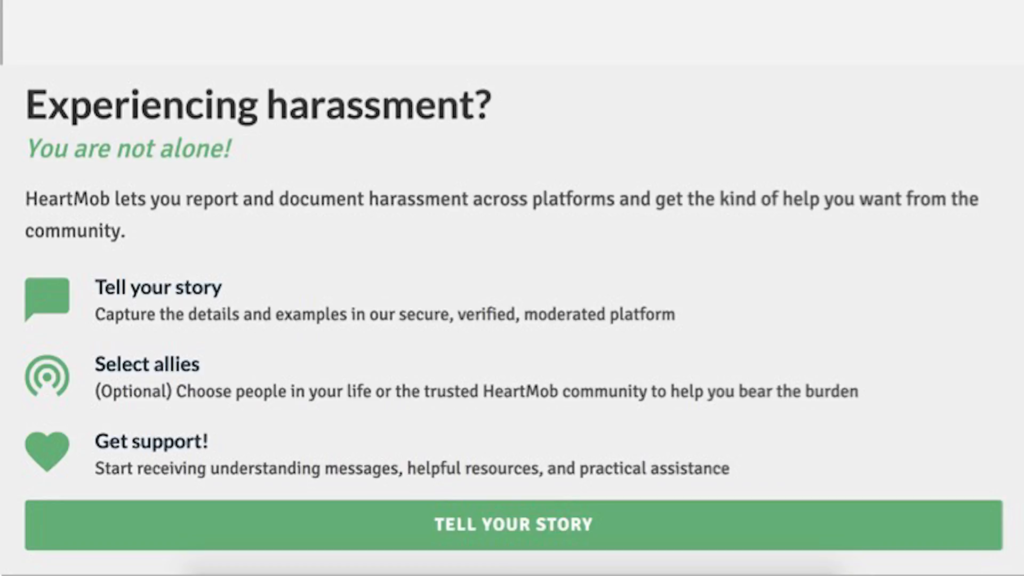

And what resulted is a system that looks like this. So if you go to HeartMob, which is iheartmob.org, as someone who’s experiencing harassment you’re told that you’re not alone and you have a few options. So you can tell your story. You can write a description of what’s happened to you. You can select allies; so you can choose people that you know, who you want help from. Or you can rely on the broader HeartMob community.

And then you can ask for specific types of support. So you can ask for supportive messages if that’s what you’d like. You can ask for help reporting and documenting abuse to platforms, so that that labor is more dispersed. You can also ask for resources and instrumental support.

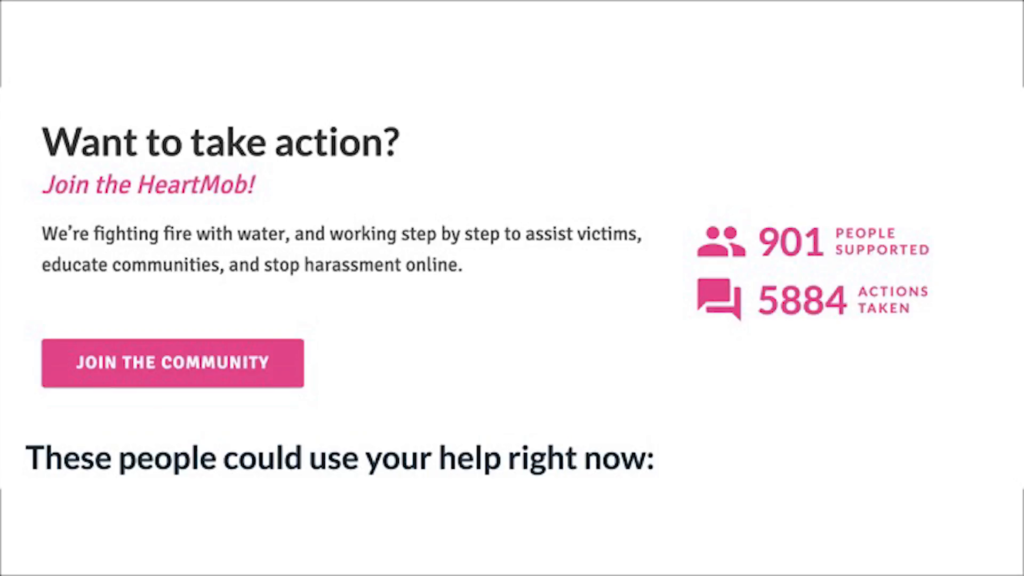

And if you have not experienced harassment, or you just want to be helpful to others who have, you can sign up to join HeartMob as a HeartMobber. And if you choose to join the community you can answer those requests for support. And you’re shown on the homepage, after it says these people could use your help right now, it shows actual cases that have been posted recently of people who are experiencing harassment and the kind of help that they’ve asked for.

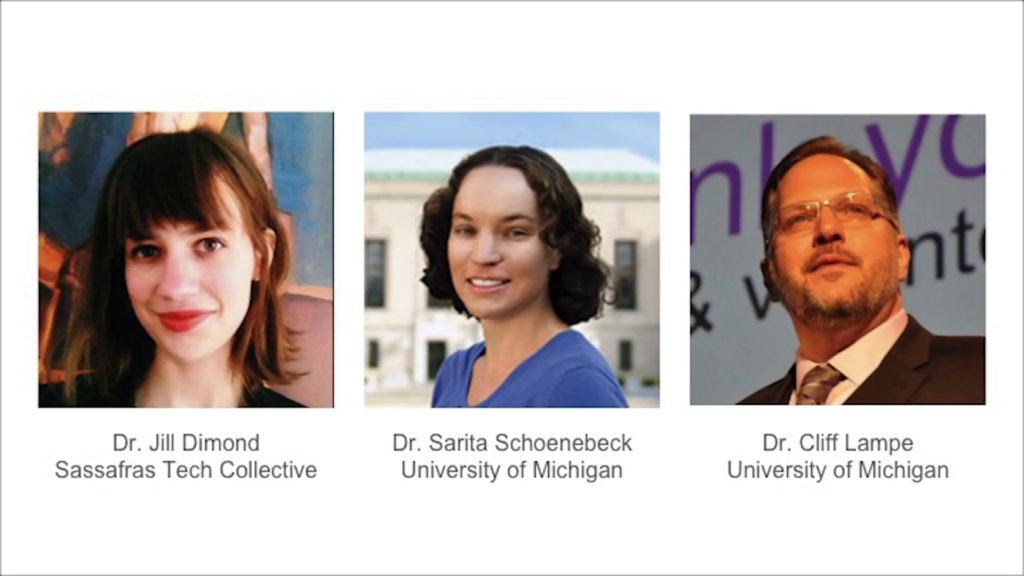

So with the help of my collaborators, we conducted semi-structured interviews with eighteen users of HeartMob. Eleven of those users had experienced harassment themselves, although not all eleven had actually posted a case to HeartMob. Seven of our participants were simply bystanders; they just wanted to be there to help. All of our participants lived in the US or in Western Europe, and our interviews were conducted in English.

And we had three major findings from this research. The first is that labeling experiences as online harassment is hugely validating for targets’ experiences. So as an example, when a user submits their case on HeartMob in that side that I showed you, they sort of check a few boxes. So they say what platform did this happen on? What do you think motivated this attack? Was it racist harassment, was it misogynist harassment? And then a human moderator on HeartMob actually goes through and reviews every single case.

And getting that signal that said your case was approved and we’re recognizing this as online harassment was very powerful for people. One participant said

It’s the safety net. Tight now, the worst that can happen is someone experiences harassment and they have nowhere to go—that’s normal in online communities. But with HeartMob, if someone says they’re experiencing harassment, then at least they get heard… At least they have an opportunity to have other people sympathize with them.

[slide]

We also heard from many participants that this experience on HeartMob of having their harassment experience validated was much different than the experience they had on major social media sites like Facebook and Twitter who often rely—because of the number of users that they have and the scale of their moderation practices, they often rely on canned responses that don’t recognize individual experiences or the impacts of harassment. One participant said

What I think was really frustrating was the level of what people could say and not be considered a violation of Twitter or Facebook policies. If they’re just like, “You should shut up and keep your legs together, whore,” that’s not a violation because they’re not actually threatening me. [Blackwell: That’s true.] It’s complicated and frustrating, and it makes me not interested in using those platforms.

[slide]

Finally, a participant said “It doesn’t have the capacity to singlehandedly solve the problem, but HeartMob makes being online bearable.”

Our second major result was that for bystanders, labeling behaviors as “online harassment” enabled people to really grasp the full scope of this problem. So one participant who actually works with domestic violence victims said that in the work that she does, she helps people understand how society plays a role in our violent culture, but she still didn’t really have a good grasp on how prevalent this problem was online. She said

I’ve never had too much opportunity to actually see the evidence on the Internet. I knew it was there. I talk about it, present about it, but actually seeing the horrific things that people are seeing and doing to others online really brought that to a whole different place for me.

[slide]

Another participant felt that because as a HeartMobber you’re shown individual cases and very concrete, specific ways that you can provide help, this made online harassment intervention feel like a much more manageable problem. “HeartMob is a brilliant way of addressing a problem that I think immobilizes most people, because it seems so big and daunting—so they don’t do anything at all.”

And finally we found that in online spaces, visibly labeling harassment as inappropriate and unacceptable is critical for servicing community norms about what types of behavior are appropriate. One participant said that the experience of online harassment is

something that’s very isolating, because it can make you feel—especially there’s multiple people doing the harassing—like everyone would be against you…like they’re representing society.

[slide]

So when someone’s experiencing this type of massive attack, they may be getting private indications of support from friends, but overwhelmingly what they’re seeing is harassment. And that makes it feel like that’s the norm.

Another person said that if they go online to support someone, and they look at the person’s other messages and they see other people providing visible support, they might think, “Oh that’s neat. There are other people out there intervening as well.” As we found that when people did see those visible signals of intervention, that started to shift the norm away from what was appropriate.

Ultimately, as you can see in our results, major social media platforms aren’t implementing systems that address the needs of the most vulnerable users online, the people who are experiencing online harassment at the most volumes. Our research suggests the need for more democratic, user-driven processes in the the generation of values that underpin these systems. Ultimately, best addressing online harassment is best served if we take the needs of vulnerable users first.

If you’d like to read the full paper it’s available at lindsayblackwell.net/heartmob. Thank you.

Further Reference

Gathering the Custodians of the Internet: Lessons from the First CivilServant Summit at CivilServant