Luke Robert Mason: You’re listening to the Futures Podcast with me, Luke Robert Mason.

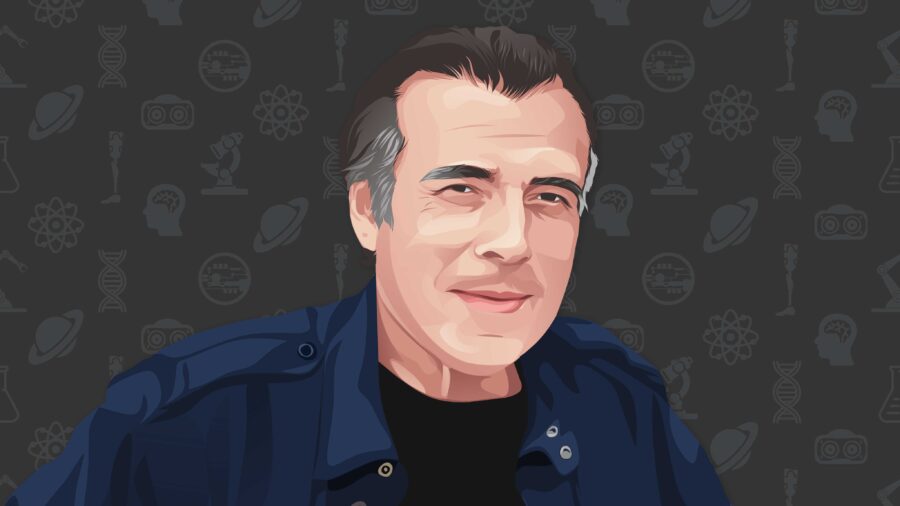

On this episode, I speak to Emeritus professor of history and philosophy of science at University College London, Arthur I. Miller.

We should not judge the work of AI on the basis of whether it can be distinguished from work done by us, because what’s the point. We want AI to produce work that we presently cannot even imagine. That may seem to us meaningless—and even nonsensical—but it may be better than what we can produce.

Arthur I. Miller, excerpt from interview.

Arthur shared his insights on machine generated work, the impact of artificial intelligence on the cultural landscape, and how computers are challenging our understanding of what it means to be creative.

Luke Robert Mason: So, Arthur Miller. Your new book, The Artist and the Machine is a philosophical interrogation of this thing called creativity. Specifically, it asks whether non-human entities such as machines and AI are capable of expressing this seemingly only human quality of creativity. I feel like the first question I should ask you is, where did your interest in the notion of creativity first originate? Is it fair to say that it began back in the Bronx?

Arthur I. Miller: Yes, by all means it did. It began in a public library in the Bronx, where I discovered classical music. I then gradually worked my way back from Tchaikovsky, first, and then back into Bach. What always stuck in my mind is: How did these people do it? How did they think of those melodies? What is the nature of creativity? But in the Bronx, at that time I was growing up—if you were smart, you went into physics, which I did. I became a theoretical physicist doing research in elementary particle physics, but those What is the nature of…? questions stayed in my mind, and so I decided to switch it to history and philosophy of physics. I read the original German language papers in relativity and quantum theory, and what jumped out at me was the role of visual imagery in the great works of Einstein and Niels Bohr, and Verner Heisenberg. I wanted to know: How did those images originate in the mind? Were they stored there for further use, or what? At that time, there was a so-called image controversy in cognitive science concerning whether images have a causal effect on thinking. To me, they did. I took part in that controversy, and it turned out that a tool that was very useful was to consider the brain as an information processing system. In other words, as an additional computer. What immediately popped into my mind was, well, can computers be creative?

So over the decades, and since the 1980s, I wrote papers on creativity. Since the 1980s, I’ve touched on machines as well. In my present book, I deal with creativity in humans, and creativity in machines—with focus on machines.

Mason: There’s something that’s the underlying thesis of this entire book—or at least the underlying assumption in this entire book, which really relies on the idea that the human brain is similar to a computer or similar to an information processing system. I just wonder how much do you actually believe that that is a useful metaphor for understanding the human brain?

Miller: It’s extremely useful, in that in the human brain, we have a memory. Machines have memories, also. We have long term and short term memories, machines have a memory. We process information, machines process information. What people seem to forget about is that we’re essentially machines—biological machines—that work on chemical and electrical reactions, which can be changed by drugs; changing our personality, for example. So there’s no reason to consider for example, that machines cannot be creative. We can be creative, machines can be creative. A pushback on that is: How can anything made up of wires and transistors be creative? But we are made up of wet stuff, of filaments of veins and the organs and eccetera, and we can be creative, too.

Mason: The only thing that makes me a little concerned about that assumption is understanding the human brain as a computer. It feels to me a little bit reductionist. It kind of takes away something very special about what it means to be human. Some have called that a very mechanistic, materialist view of the brain. I just wonder if we are so willing to understand the human as a form of machine, does it obscure, perhaps, the true nature of creativity.Is there something hiding within human beings that’s very special, that gives rise to creativity, that maybe machines can’t replicate?

Miller: There’s no reason to attribute creativity only to humans. Yes, it is a very reductionist view—we might say mechanistic, materialistic—to use old jargon. But we are—our brain is—essentially made up of electrons, protons, neutrons, gluons…the whole zoo of elementary particles. All of these particles can, in principle, be understood using the laws of the equations of quantum physics. These equations, when put on a computer, become numbers. So it’s numbers all the way down. Machines deal with numbers too. So there’s no reason why machines cannot be creative, cannot have emotions and cannot have consciousness. It doesn’t take away any of the mystery of life. Because all of these elementary particles act differently in different people. I mean, it’s obviously not an even sea. Some people are born smarter than others.

Mason: I just wonder if you can share your definition of what creativity is, because you help to define that within the first couple of pages of this book.

Miller: My research on high calibre thinkers—highly creative people, I’m trying to say. From that work emerged my theory of creativity. What emerged from that is that creativity can be defined as the production of new knowledge from already existing knowledge, accomplished by problem solving. That definition includes both process and product. I look at problem solving with a four stage model of conscious thought, unconscious thought, illumination and verification. In the conscious thought stage, the researcher sits at their desk and works consciously on a problem, and the researcher will get stuck somewhere along the line. The experienced researcher will take a break. But you take a break only consciously, because the passion and intense desire to solve a problem keeps it alive in your unconscious, where it is turned over in ways not accessible to conscious thought, owing to the barriers and inhibitions there. Then it’s along these lines that the illumination or problem solution crystallises and bubbles up into consciousness. In that conscious stage—that’s the verification stage—which is important because the solution to a problem doesn’t emerge in its final form. It has to be fixed up. Deductions have to be drawn from it. Now running through all of this—lacing through all of this—are what I call characteristics of creativity, which again emerge from case studies. Characteristics such as inspiration; suffering; perseverance; focus; being out there in the world and having worldly experiences; unpredictability; problem discovery—that’s a big one; and finding connections between disciplines that everybody thought was unconnected. So my view of creativity is fine grain and includes the angst of the creative act, the lust for knowledge. As Picasso put it well, creativity is everything.

Now I claim that machines can have those characteristics, too. For machines to be fully creative, they must have emotions, and consciousness. If you notice, some of these characteristics contain an emotional basis. The combination of emotions and unpredictability is explosive and can give rise to the big idea.

Mason: The thing was so nice within those early chapters of the book is he focused on this idea of not just conscious thought, but unconscious thought. We fixate so much when we talk about AI on conscious beings, but you elevate the importance of having this unconscious thought, or being able to walk away from a problem, and then for the solutions to potentially arise. But I struggled to come to terms with the idea that machines are capable of unconscious thought.

Miller: It’s difficult for machines to have conscious thought at the present time because they have no consciousness. You have to feed the problem to the machine. My definition of creativity goes over to machines very easily because machines work on accumulated knowledge and they’re problem oriented. So a machine receives a problem, or we put a problem into it. It mulls over this problem. It applies all the data in its database to it—that’s unconscious thought. Then it can be the illumination when the machine solves the problem. If you were talking about a human being, you would say that that person takes a leap of intuition. So, you know, why can’t the machine do that? I’m not using intuition, in any magical sense. Intuition is a skill which is honed. I mean, we’ve seen or heard about art connoisseurs taking a look at a statue that has emerged in an archaeological dig. Taking one look at it and saying, “It’s fake, it was planted.” That’s not magical in any way. That person has made a huge number of mistakes, and machines are making mistakes also—when they are looking at a problem and trying to fit data to it.

Mason: Again, my issue with this—the unconscious thought—is how you describe in the book: A human being can be doing something else completely alien or different from what the problem is that they’re trying to solve, and then suddenly in that moment—that embodied moment—the solution presents itself. That makes me think that the only way in which AI or machines can have these unconscious thoughts is that they have to be embodied. They have to be able to exist in the world and to be doing other things that may not allow them to fixate on the problem that they were programmed for.

Miller: Well at this point, the machines can only do it in this closed off space. There will come a time when machines will be set into robots, as their brains. Then they will move about the world, and by touch, they’ll improve their notion of What is touch? What is intimacy? and so on and so forth. Then they’ll be doing something else. But right now they can only do one thing, and that’s pretty good when they do that one thing.

Mason: Within that one thing that machines can do, I just wonder how many of those expressing forms of creativity? Now in the book, you look at seven hallmarks of creativity. I just wonder how close machines are to achieving some of those hallmarks of creativity—the machines that we have today?

Miller: Well, machines today can be inspired in the sense that the machine makes a good move in Go. Then the innards of the machine are adjusted, so that when the machine is in that circumstance again, it will make that move. It will be inspired to make that move. Just as when we make a good move in Chess or Go, we keep that in our memory, and then when we see that situation coming again we say, “Aha, I can do that.” So we’re inspired to make that move.

Suffering will come along, okay. Suffering goes along with awareness, which machines don’t have. Machines don’t know whether they made a great move in chess or composed a great melody. But machines have a basic sense of awareness in that they’re aware of the problem they’re working on, and they’re aware of their own wiring. When their wiring is tampered with, they could give messages, “Something’s wrong here.”, and hopefully they won’t react like HAL does in 2001. Perseverance—machines persevere. They don’t get tired, they go on and on, which is why it’s great to have robot arms assembling cars. Robot arms don’t come into work with any distress from a bad weekend. Focus is focused on.

Machines have unpredictability, because although there are separate parts which are assembled according to Newtonian physics with its determinism and causality, when these parts are put together into a hole, they can exhibit chaotic behaviour. That is, say, unpredictability. Once machines have emotions, then they have true creativity. Combine that with unpredictability.

Problem discovery and finding connections between disciplines that don’t seem to be connected. Machines can have that in a primitive sense, even at this point. Although certainly when they have natural language processing; that is to say, when they’re fluent in a language, then a machine can survey the web and, say, look at the field of physics, look at a particular area of physics and see that it’s cluttered with redundancies and inconsistencies. That’s usually a sign that the wrong problem is being worked on. What a machine can do at that point is to look at all the disciplines that are connected with that field—even tangentially—ones that are all the way out in left field. Then all of a sudden they can see that: Wow, one of these obscure ones really has something to do with his problem situation. That can lead you to something new again, you have this leap of intuition. Then the machine might compose a new problem and work towards solving it. Now that that way of looking at scientific research will have great dividends already, to a certain extent. We have machines that have a huge amount of knowledge. When a machine can read the web, it will have all knowledge that has ever been set up on the planet. Based on that knowledge, it can propose hypotheses that can be radically different from the human scientist who works on just accumulated knowledge that he or she knows about. It is in that way that machines can come across knowledge that we don’t know anything about. The great move that AlphaGo made in its chess match in 2016. That was a move we might say of genius. It changed the game. People play differently now, looking at the way machines play.

Looking even further at this and in the realm of the social sciences. When, say, we’re negotiating a treaty—the US is negotiating a treaty with Russia—and we might put some statements in the treaty. Then you might want to play the game, but, “How will they react? If they react in this way, then we’ll do that.”, and so on. Playing these games—humans can play them but with their limited realm of knowledge. Machines can play it with their much wider realm of knowledge. You can do this with music, too. Looking at different genres of music that don’t seem related, machines will find the relation. Maybe they’ll discover or create a new kind of genre of music that we knew nothing about.

Generally, what I’m getting at is that machines can improve our lives. We’ve done a miserable job on this planet, we haven’t planned ahead in any way. Machines can help us along those lines. Also we are merging with machines, so it would be good if we went from humanity 2.0 to 3.0, and 4.0— that will help us survive.

For example, if climate change really gets difficult, it may be that we will have to change faster than the Darwinian timeframe. Another reason why I wrote this book is to give another view from the dystopian view of machines. The cultural side of AI.

Mason: It feels like there’s so much in the answer that I don’t know where to go next, but I do want to look specifically at the case study that you just alluded to of AlphaGo, because in the book you look at these gaming AIs as exhibiting forms of creativity. AlphaGo had that move that was considered by other AlphaGo players to be a very creative act. What is AlphaGo, IBM Watson, Google’s DeepMind—what are these current AI products teaching us about creativity today?

Miller: Well, they’re teaching us to be on the lookout, essentially, for new ways of approaching problems. What we’re also learning is looking at how this process works. Researchers use essentially two different types of machines for this. They use symbolic machines, which are loaded with software databases and complex rules for using the databases. Our laptops, for example, are symbolic machines. Deep Blue, the machine that defeated Garry Kasparov and cracked the game of chess is your laptop on steroids. On the other end of the spectrum, our artificial neural network machines—which are minimalist machines that use a minimum of input algorithms of software. Both proponents of both machines actually claim that they are the way that the human brain works. So what these machines show us is how we use our databases. That the databases that we’re trained on allow us to react to the world in which we live.

Mason: What’s interesting is how you really do argue for the creativity within the machine. The way in which you open up that possibility is to see not just art as a creative act, but to see science and to see problem solving also as a creative act. How is art and science united through this thing called creativity?

Mason: On machines, AI created art. You have a new species of artists. The person who is the artist and technologist rolled into one. That’s good because in the 21st century, art and technology is merging. Music and technology is merging, and so is writing and technology. Those are the new frontiers, where we’ll see the new works. I mean, eventually, machines will create art, literature, music, of the sort that we personally cannot even imagine.

Mason: The book is littered with these wonderful case studies of where we’ve seen machine and AI artists, and the agency problem. How do we deal with artwork that is created by machines? Does it always need a subjective human viewpoint to see it as art? Will we ever get to the point where AI will create artwork purely and only for other AIs?

Miller: Well, that’s a big and good question. There’s always the issue of: Machines can create art, but are machines artists? But what you can do, for example, as a first approach to that problem is you can put a webcam on a robot artist. Take it outdoors and it will look around, and something will attract its eyes. Some shape, some particular geometrical shape. It will want to draw it, want to paint it. That’s a primitive sense of volition, and freewill as well. That’s part of the issue—that people argue that machines aren’t out there. They’re not having worldly experiences. But what machines can do is to have fluency in a language, can read the web, and can read about thirst. It can vicariously convince itself that it’s thirsty and us too, and then it can read about love and think: Well, that’s cool. It can watch movies and can learn more about love by watching movies, watching TV, eavesdropping on conversations between us all via the web. Then it can think to itself: Well, I had a good conversation with a machine down the street. I think we’re in love. Then it can think about intimacy, and can learn more about intimacy by reading novels. Then it can be embodied in the robot—it can develop a sense of touch and feel more intimacy there. It will certainly come to pass that artificial intimacy will be the real intimacy. The line will vanish between the artificial and the human intimacy—there will be just intimacy. I mean, we have sex bots. They’re coming online, and imagine what that will do to human relationships. But by that time, the notion of what a human being is will have been transformed, because it’s changing faster than a Darwinian rate.

Mason: But again, it goes back to this agency issue. If machines have access to the wealth of human created knowledge, surely the sorts of experiences that it’s going to have are going to be defined by the ways in which humans have codified their understanding of these things.

Miller: Right now it is yes. I mean, you could look at the various possibilities you have. Right now, you don’t need very much technical ability to do AI art.You can buy an algorithm off the shelf that’s already been trained on say 50,000 images of people from the web, and then go home. What is often done is a person puts a selfie into it, and then dials in the style of Van Gogh, and out will come something in the style of Van Gogh, but it will be slightly differently in that elements of your face will pick up elements of faces in the data set, and you will be slightly changed.

Then you might want to be creative and put that back in and dial in the style of Cubism and then what will come out as a superposition of your face as Cubist and Van Gogh. But it will again be changed even further, through further interaction with features in your face with what’s in the data set. You could be more creative, do that a few times and then pick out one that you can put into a contest, say. Okay, so in that case, creativity solely has human agency, but then you can go on and you can have situations where the creativity will be shared between the human and the machine. That’s in Deep Dream, where a human wrote down an entirely new code and used an artificial neural network trained on a huge image net data set of 14 million images. What came out is images that were far from what was in the data set. So the machine essentially jumped the data set.

Then you can have humans and machines working hand in hand, so to speak, each bootstrapping their own creativity—for example, in music. Francois Pachet, who is a musician and computer scientist, Director of the Spotify Creative Technical Research Lab has always been interested in coming up with devices that can aid musicians and composing, and playing music. One of them is a device which can improve musicians creativity in improvisation. Pachet is keen on jazz, and he calls this device Continuator. It works along the following lines that the musician begins to play on a piano, and that train of notes is fed to the continuator AI device which parses it out in phrases. Then these phrases are sent down a pipeline to a phrase analyser, which picks out patterns. It’s along these lines that the Continuator improvises in response to the musician. The musician then turns around and improvises in response to the Continuator. So improvisation is often defined as a conversation between musician and musical instrument. Here, it’s a conversation between a musician and AI.

Mason: When I struggle with is: Where does the artist begin and end? Is the nonhuman agent the artist, to a degree? Is the human who’s programming the AI the artist? Or can it be considered the only artist? For example, if you have a painter, it’s very clear that they’re using a paintbrush to manipulate paint on the canvas and therefore the agency of that artwork—or the agency of the person who’s creating the artwork—sits with the human artist. But if they were painting with slime mould for example, and it would land on the canvas and then grow across the canvas and create its own morphogenic forms, the question then becomes: Is the artist the human, or iis the artist the slime mould? In all of those sorts of examples you just gave, how do we give credit to the correct artists, or do those things really matter? Is it always going to be a human artist if there is a human in the loop in the creation of the work?

Miller: Sometimes agency is shared between human and machine. In that case, it’s often a situation where the artwork is signed off with the signature of the human and the machine. When machines have volition and free will then they will be real artists. That is not yet totally the case. Then the machine will have agency.

Mason: I guess then the problem becomes—once this work’s created—who gets to appreciate it? Is it always going to be human subjectivity, human audiences that are going to define something as artwork, or can the AI also contribute to whether they see something as an artistic endeavour or not?

Miller: Well, there will come a time when the AIs will have emotions and consciousness and then they can appreciate the work that they’ve done, and they’ll do that work for us and their brethren.

Mason: Right now today, do we as human beings, and does the art world even appreciate machine generated art? Is it the fact that it’s instantly replicable, it seems very easy to do—as you just said, you can plug something into a computer, press a button and out comes the artwork. I guess, will we ever appreciate machine art? Could there be an argument that we will never appreciate machine generated art until there is a monetary value put on to it?

Miller: I think that whilst we bear in mind the question, “Can machines be creative? Can they create art?”, we should also bear in mind the question, “Can we learn to appreciate art that’s been created by machines?”. From a monetary view, yes there is appreciation. At an auction at Sotheby’s last year, a piece by the very prominent and brilliant AI artist Mario Klingemann was sold for $50,000. Just a few months before that, a much less creative work of art was auctioned by Christie’s for $432,000. The drop in price might have been because the uniqueness of AI art wore off and there was a big tumult about this $432,000 sale. But nevertheless, AI art has hit the high end of the art market, and it is being appreciated up there. I mean, it’s a great conversation piece for your living room, for example—to see a work of art constantly changing. So it is of monetary value, and it is in appreciation.

Mason: In examples like that. It is the algorithm that’s created to generate the artwork also seen as part of the artwork—as an artwork within itself?

Miller: It’s something that is producing art. As time goes on, as machines become more sophisticated, they will have volition and will be producing art themselves. The point is that you want to have the machine come up with a problem—the art problem that it wants to solve. Right now that is inputted. We have to kick off the process.

Mason: Does the problem of true creativity get stifled by the fact that it’s humans at one end that define the art problem to expect some sort of art output?

Miller: That’s right. Precisely as I’ve said, the human has to kick off a situation. Machines are not yet at the point where it can choose a subject.

Mason: It feels like from reading the book, your hope is that eventually the human will no longer need to be in the loop.

Miller: That’s right. As I discussed previously—that chain of first person with the selfies, and then Deep Dream and so on—the last step of that is machine working by itself. Now similarly, right now it’s mostly the situation where we have humans and machines working together, but eventually machines will go off on their own. In literature, they may produce literature that we cannot understand whatsoever. They’ll have to explain it to us. And maybe at the end of the day it’ll be better than what we can do.

Mason: In the book, you focus on three things that AI can currently create in the cystic domain. That’s visual artwork, literature, and music. I just wonder why you focused on those three? Is it because they’re the lowest hanging fruit in terms of what AI can actually generate? Or are they very specific creative endeavours that you feel are at risk by these AI entities?

Miller: No, not at all. I discussed those three because an aim of my book is to discuss the upside of AI—the cultural side of AI—which is something that’s not discussed very often. Most of the people in AI are engineers who deal with driverless cars and drones, and things of that sort, which is all well and good. A small subset deals with AI creativity. Also if you speak with engineers in AI who are not involved in AI creativity, they haven’t the foggiest idea what goes on in that area, and they’re not interested in it either. Unfortunately, dystopian books are very popular with the public, and these dystopian scenarios aren’t going to take place for maybe 100 years. These days, it’s dangerous to predict more than five years ahead owing to how fast things are changing. So 100 years from now, we’re going to be very different. Our relation to machines is going to be very different. A good many people on the planet will be mostly machines. I mean, I think there’ll be three sorts of life living on this planet. Human beings who are not merging with machines, who prefer not to; human beings that are; and machines.

Mason: If we were to have that sub-speciation of cyborgs, of animals and of humans and then machines, and AI—do you think they would each live in different artistic and aesthetic domains? Do you think that each would have their own artistic language? Or do you think there’ll be some new emerging aesthetic language to describe this co-living of different forms of species?

Miller: So there will certainly be a different aesthetic language, whatever aesthetics means. But it may be that these three different species may be living in different areas—they may not coexist. Putting aside the humans who don’t want to be transhuman—they’re going to be left behind, I think. What we want is to be in good relations with machines, all the way through. Teaching machines to be creative can be extremely useful here. But again, we can’t predict what our relations with machines will be. Indeed, there may be rogue machines—there are rogue people too. We create machines. You have to begin somewhere—machines have our creativity. There will be—perhaps not too distant future—what’s called artificial general intelligence. That will be where machines are as intelligent as us. They will have evolved a set of emotions, consciousness and creativity which are duplicates of ours. So there will be the line between artificial intelligence, which is an oxymoron, and natural intelligence will disappear—there will just be intelligence. Then the next step—who knows how long that will be, maybe not too long—there’ll be artificial super intelligence, where machines may have evolved a set of emotions and consciousness which are totally different from ours, whatever that might be. But one thing is for sure that machines at that point will have a creativity that far outstrips us, because machines have the potential for unlimited creativity.

Mason: Will machines even value creativity? It feels like all of the discussions around super intelligence are moving towards ideas of the singularity. It’s moving towards greater efficiency and greater economic efficiency, and machine-like efficiency on how we operate and live in the world. Will the creation of artwork be seen by these super intelligences as a pointless endeavour, perhaps?

Miller: Oh no, they will value aesthetics. They will value creativity highly. They’ll have super creativity. As a matter of fact, they can work along with us and we can put our own unique creativity in there, as well. And again, we’ll be entirely different. You can’t even predict what sort of mindset we will have. But creativity will still be valued. The works of art they produce, the literature and music…again, we can’t even imagine what they will be. But I picked those three subjects, because they’re their cultural subjects. And I wanted to indicate a cultural side of AI.

Mason: Let’s focus on one of those cultural elements, which is literature. Because there’s something so lovely that you say in the book about the fact that AI literature actually challenges our notions of what we perceive to be nonsense and what we perceive to be poetry. In actual fact, some of the AI literature that we’re seeing and in some of the case studies that you give within the book, we’re actually seeing the sorts of outputs that are very similar to the big poets or to William Burroughs, and that seems very hopeful. That there’s a degree of creativity, at least in the literature space.

Miller: Yes. and there’s a degree of abstraction, too. Some of these texts are rather nomic. They have very little subjective meaning, one might say. In that sense, the reader becomes the writer, okay, so there may be text along those lines. But certainly, machines can transform the landscape of language. They can transform the progress of literature just as they’ve transformed the progress of art and music as well. There’s programming involved in some of this, especially when it’s done with symbolic machines—less so with artificial neural networks. Nevertheless, one should not criticise this work as being just the result of programming, and machines are the servant of the programmer. I always like to tell the story of Leopold Mozart. His father taught him the rules of music, but we don’t credit the father with the son’s music. Similarly, we don’t credit the AlphaGo team with the great moves that AlphaGo made. So you have machines jumping their programmes, jumping their algorithms.

Mason: The one thing that we’re still struggling with when it comes to at least AI created literature is the idea of humour, and the idea of sarcasm, and there’s a good argument to be made. The reason why we struggle to programme that into AI is because they’re not present in the world. They have no context on the human world to make the sorts of comparisons that give rise to things like puns. So is there an important step that we need to take, to take this AI out of its black box where it’s creating artwork and find a way to embody it so that it can experience the lived reality, the lived world? To truly create artwork in a way similar to the ways in which human beings create artwork, by taking inputs from the world through our sensory organs, and then—through unconscious thought or otherwise—we’re then able to process that and output this thing that we’ve notionally called artwork?

Miller: Absolutely. I mean, what one needs is machines to be truly out there in the world as the brains of robots. Experiencing their contact building up, sort of like the way the psychologist Jean Piaget thought of a child constructing reality; the robot moves around the world and sees the relationship between objects and then builds up a notion of space and a notion of time. What one needs perhaps is an Einstein for AI, who will say, “No, you’re all working on the wrong problem. What you need is…” What we know we need is a really revolutionary architecture. Artificial neural networks are doing a great job now, but there may be something better than that. After all, you look back at Leonardo da Vinci and others who were studying flight, and they put wings on their arms and flight was…well, if you emulate birds, you’ll get there. But a 747 aeroplane does not fly like a bird. So it may be the case that progress in AI will not proceed and will take off from what’s going on. But actually what’s being researched these days is called hybrid machines—machines that are part symbolic machines, part artificial neural network machines. In fact, some very interesting work has gone on in Deep Mind where they’ve succeeded in having an artificial neural network evolve a symbolic-like algorithm. Because the holy grail at Google is for end-to-end training using only artificial neural networks, and nothing else. It’s doing a great job now, but it may be the case that somebody will come along and say, “Well, look. Here we have this very interesting architecture.” It may be that an architecture of the future will be part wet, part human cells and part machine.

Mason: Should we be looking at not artificial intelligence for where the future artists may come from, but artificial life? Should we be looking at the sorts of works that are being created in collaboration with non-human agents like bacteria or slime mould? Are we closer to having these fully realised artworks that emerge from the creation of artificial life than we are the creation of artificial intelligence? Are we looking in the wrong place? Should we be looking at vitality itself rather than intelligence as the thing that we put on the

pedestal?

Miller: We don’t know. The point is, the great progress right now is being made in AI with both symbolic machines and artificial neural networks. Artificial life has given rise to some interesting music compositions such as in the hands of Eduardo Miranda at Plymouth University.

Mason: There are so many wonderful case studies in the book of examples where machines are generating artwork. Is there one, particularly, that really encompasses all of the things that you’re trying to grapple with when it comes to this idea of creativity? Is there an artwork which is exemplary in terms of showing all of those different forms of creativity?

Miller: Perhaps what comes to mind is Ahmed Elgammal’s creative adversarial network, which creates new art styles.

Mason: And yet, when we look at something that we can’t help but reference pre existing styles. Can we really find something that is truly new, and will it come from machines rather than from humans?

Miller: It will come from both, but what one wants to see is this coming from a machine. I can’t really answer that question right now because machines are just not at that stage but the glimmers of creativity are absolutely amazing. Again, AlphaGo in the spectacular move it made in its match with Lee Se-dol; a move that wasn’t supposed to be made at that point in the game, but it made it and it changed the way Go is played, and it also won the match. Even with a primitive symbolic machine, Deep Blue, which defeated Garry Kasparov in 1997. The 44th movement made in the first game of the match—it was a mid-game move, and it faced a situation and it couldn’t find what to do from its playbook. So it jumped the playbook and came up with a spectacular sacrifice. Then there’s Deep Dream, which produces some extremely interesting artwork. In fact, it kicked off a whole new art style, which is still being used today. There’s creative adversarial networks, generative adversarial networks where machines can dream essentially, and produce interesting artworks. There’s Continuator which I mentioned before, Francois Pachet’s Continuator, which produces new improvisational melodies which are very pleasing to the ear. There’s the so-called 90-second Melody produced by an artificial network machine. It’s the first melody produced by an artificial network machine and the first melody produced by any machine which was not programmed and with databases for producing music. Then there’s the surreal prose that’s produced by artificial neural networks.

When I first thought of this work, I knew a lot about AI created art and AI created music, but not much about AI created literature and I thought: Well am I going to have enough? I had more than enough. So no, I can’t really focus on one piece of work there. Wonders are produced by AI.

Mason: What you’re very good at is looking at how culture and society, how the current science affects the way in which certain aesthetics or artwork emerges. Famously, you’re known for looking at the relationship between Einstein and the work of Picasso and I just wonder, is the work or the machine generated work that we’re seeing today—is it actually having an inverse effect? Is it changing the way in which human artists create work?

Miller: Yes, absolutely. AI created artwork has changed the way that artists paint and work in a number of ways. One very interesting way is that artists now train an artificial network machine on their own artwork, and then have the machine produce their own artwork, essentially, but variations on their own artwork. Some certain variations will be surprising, and then the artists will use that variation in their own painting.

When humans work with machines, we have our own database of knowledge, which is not as deep as machines. Say machines and scientists are working together on a problem. The machine can affect the scientist’s creativity in that it can, in an instant, read all the papers on a particular subject, and relate that information to the scientist, who can then adjust the hypotheses that he or she is making on a particular problem. So it kind of has a human’s creativity,

Mason: Your desire to put AI on a pedestal is very much to do with an obsession that you seem to have with geniuses and high achievers, and you’re looking at AI as potentially the next example of genius out in the world. Where does that fascination with geniuses and with high achievers come from?

Miller: A genius is somebody who has extraordinary intellectual abilities which do not arrive by means of deliberate practice. It arose from reading about high achievers like Einstein, Picasso. People who are looked up to by all people in that profession. That’s where my penchant for high achievers came from. What one can do is to study them—which is what I’ve done—by applying various psychological theories such as Piaget’s epistemology, Gestalt psychology, Freudianism and so on, and try to get some indication into how they thought. There’s a paradox here—that I’m using psychological thinking theories that were formulated from the thinking of average people and applying that to above average people, but again you have to begin somewhere.

Mason: It feels like in some of your work that you have a desire to find the formula for genius, and yet it feels like what unites the sorts of geniuses that you obsess about or are interested in, is the fact that they’re all completely different.

Miller: Yes, they’re all completely different. But, there’s a fundamentality there in that they’re all extremely smart. One of the goals of my work is to try to get some handle on how they think. Though we can never think at the level they do, how they work can help our thinking.

Mason: When it comes to genius, are you trying to find a quantitative value that points at genius? For example the IQ test. We can say that if someone has a certain IQ above a certain value, therefore they are a genius. Sometimes, what makes someone a genius isn’t related purely to intelligence. When we look at genius and equate that to the obsession around artificial intelligence, is genius all about intelligence or is there something else going on? Is some genius not always purely on intelligence? Is it reliant perhaps on something like creativity?

Miller: Well, creativity is part of intelligence. Intelligence is kind of a fuzzy thing, and there are various sorts of intelligence. Emotional intelligence, scientific intelligence, logical intelligence, musical intelligence and so-on—and that’s of course related to creativity. There’s a difference between talent and creativity. Someone can be very talented but not be creative. Someone can be a very talented piano player and won’t make any mistakes but there’s something just missing in their rendition, whereas a creative pianist adds something to it and draws out what’s in the score. The converse is true, in that if you’re creative then you’re somewhat talented. There have been highly creative musicians who have turned out not to be great pianists, but they’re not bad anyway. Yes, machines have the capability of genius thinking. Genius is a way of thinking.

Mason: There’s something so nice you said there, about how you can be an extremely talented pianist and play all of the right notes in the right order at the right time. I just wonder if that’s where we are right now with AI—they can replicate music, they can play all the right notes at the right time, on the right beat…but they perhaps don’t have that creativity to go slightly off-beat. You can talk to drummers about the creativity within how Ringo Starr used to drum—he used to drum off the beat—and yet machine generated algorithms that are used in music production software demand often to put the drum beats on the beat, which would make the beat of sound absolutely awful.

Miller: That’s the embodiment problem too. Machines have to be embodied into robots so that they can use their body when they play the piano. You see great and creative pianists putting their bodies into it. They use their emotions and so-on, instead of sitting up straight in a chair and just making sure they hit all of the right notes.

There is, in my book, a case where a musical score is played by a machine and there’s no emotion in it whatsoever. There’s no loudness and softness, and so-on. The same score is played by a pianist and it sounds entirely different. In fact, I think there was an experiment where Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata was played by a machine. It was just plodding along. When played by a person who puts their body into it and their empathy into it, it sounds entirely different.

Mason: So you think to solve the problem of that ephemeral experience you get when you witness human created music or artwork, all you have to do is ensure that the machine that is playing is embodied?

Miller: No you want the machine not only to be embodied but to have emotions. You need emotions and consciousness for full creativity, whether it’s doing art, science, literature and certainly music.

Mason: What I’m really trying to ask you, Arthur, is do you think there’s something special and unique about human beings that can never be replicated by machines, that can never be surpassed by machines?

Miller: No absolutely not. When you say human beings, you’re talking about human beings right now. But human beings will change and machines will pick up all of our characteristics. Indeed, when it gets to a point of artificial super intelligence and machines start reproducing themselves, there will be some of our DNA in there, so to speak. We’ll always be bound together. But no, there’s nothing special about human creativity. There’s nothing special about us. We’re just an accident. Some billions of years ago, an isotope of carbon in the sun just spat out atoms that landed on Earth, and here we are. There could be lifeforms elsewhere. This notion of looking at exoplanets for the so-called Goldilocks Zone. Life as we know it need not exist anywhere else in the Universe.

Mason: I strongly struggle to believe that there is nothing special about human beings, because in many cases artists create artwork to express the nature of the human condition. It’s a very human process to generate and create artwork.

Miller: Back in Babylonian times, Babylonians had a cosmology. The Earth stood in the centre, planets moved around it, and that lasted until Copernicus and Galileo. The Earth has moved out of the centre—the sun is in the centre—but that’s okay because that’s our universe. Then the galaxy was revealed, and we’re just one of many star systems. Now we have a multiverse, where our universe isn’t even unique. So no, there’s no reason why humans should be unique either. In fact, as I wrote at the end of my book, there will come a time when this whole enterprise will run down. The universe will run down, and the only things that might be left are robotic forms, and they’ll be smart enough to know how to get into another universe. Once they land on a planet, it may not be like ours and they’ll have creativeness of their own, and this whole process will start all over again. So, there’s no reason why we should be unique.

Mason: Well at the end of the book, you proffer some challenging notions of what the future may look like. One of those is the idea of the cyborg artist. The combining of humans with AI or machine parts. I couldn’t help but think that we already have cyborg artists today. We have people like Neil Harbisson, the colourblind artist, who has an antenna that’s surgically attached to his head. The interesting thing about Neil is that although he’s a colour bind individual and the antenna allows him to hear colour, he defines it as an entirely new sense because what the antenna’s actually doing is converting light waves to sound waves. Instead of putting those through the traditional aural senses of the ears, what it does is it vibrates his skull, so he’s experiencing this entirely new sensory modality and then he creates these artworks—these very colourful, representational paintings—that only he can truly experience, because they’re sonic. Humans that don’t have an antenna, or individuals who aren’t enhanced aren’t able to have the same experience with an artwork as someone who has an antenna or who has been enhanced can have. Are we going to get to the point where you’re going to have to start enhancing yourself to experience the full spectrum of possible future artworks?

Miller: These artworks will be very difficult for us to understand right now, at this time. Even looking at electronic art—the best way to appreciate that is to know something about computers. It isn’t the sort of art that you see in the Tate Britain where you can walk up to it and put your hands behind your back, looking at it from various angles and seeing the paint swirls and things like that. AI art will be even more different than electronic interactive art. We will be able to appreciate it. We have to change our mindset and realise that this is art not produced by human beings, but by a machine. As time goes on, and we become closer to machines, and machines produce art that we might not understand at all, they’ll have to explain it to us—just as they’ll have to explain their own prose to us as well in order for us to appreciate it.

Mason: But will we have to actually fundamentally change our minds? Will we have to enhance our minds to be able to have the experience with a piece of AI created artwork?

Miller: We’ll be transhumans by that time. Our modalities will be stimulated in a variety of ways.

Mason: Today, right now, as we’re increasing our scientific knowledge about the world and learning more about ideas like quantum mechanics and weirdness and how things are extremely different when they go very, very small—how is that impacting the way in which artists will start to see the world?

Miller: As far as the quantum world…certainly to me, the quantum world is not weird. That’s a mistake. That’s something that people try and sell books with. It seems to us to be strange because it’s against our Aristotelian intuition which is that heavier objects fall faster than lighter ones—and they do—except in a vacuum, and intuitions of that sort. That objects have a place and that’s it, they’re not disembodied. In the quantum world, an electron can be everywhere until you make a measurement.

Something that’s interesting, which is to come yet, is art produced by quantum computers. Quantum computers are at a fairly rudimentary level now but they have an awful lot of money behind them presently, for financial purposes.

Mason: Is that art that could be in every single gallery simultaneously until you observe it?

Miller: Very good. I’m just thinking of getting a piece of art out of that machine, because you can’t touch a quantum computer while it’s working. You then destroy the entanglement. That’s a problem that’s yet to be solved.

Mason: What is strikingly clear in the book is that you really do believe our future machines will surpass human beings in terms of creativity and that AI generated art will exceed human artist’s wildest dreams. Does this then mean artists become obsolete? Will we have the obsolescence of the human artist, or will we constantly desire human created work because we’ll see machine generated work as something that comes from the uncanny valley or the [inaudible] valley? Could it be something that’s very difficult for us to let go of?

Miller: Looking at electronic art, a lot of people in electronic art call portraiture, “flat painting.” People who do brush and paint will go on—that will go on. That art will still be expensive to buy, so people will turn to AI created art which will be much cheaper. There will be AI art done by machines by themselves, and then there will be art done by human beings in conjunction with machines, combining the unique aspects of both of them.

Mason: Finally, I want to look at what you end the book with, which is this playful provocation that in actual fact, what may end up happening is when we sub-speciate and some individuals become cyborgs, some individuals choose to remain human and then we have these AIs that are then able to transcend biological form and go off into the stars and populate other planets, that they will be able to then finally create, unhindered by the limitations that we’ve set ourselves here on Earth. How far do you actually believe that space exploration in itself will be a form of creative endeavour that is performed by our machine successors?

Miller: These new forms of life, these cyborgs of life, which may have wet insides—we don’t know—they’ll find a way to move into another universe. What I’m saying is that they’ll populate these planets and there will be maybe an Adam and Eve to start a whole new race over there of human beings. We may be like that. Our insides are wet, but we may be the end result of a lot of experimentation.

Mason: Or a lot of creativity.

Miller: A lot of creativity too, yeah. Right now, the best way to do space exploration is with robots and it will continue like that for a long time. The way to get to other star systems will only be through discovering a wormhole. People like that statement, science fiction fans like that.

Mason: It’s a beautiful idea, but you talk about these machine entities or these cyborg entities that will go off and populate other planets. I just wonder how space itself will change the way in which we create and generate work. How will we create artwork, or sound, even, in vacuums of space?

Miller: Those life forms of the far distant future will be generated from us, essentially. So they will need gravity and the properties of the Earth—whatever they may be—when they leave.

Mason: Is it going to be a case of slow attrition? Are we of the mindset now where we are so reluctant to see creativity within machines because we’re scared of what that means?

Miller: Precisely.

Mason: Will it be the case that we’ll see incredibly creative outputs, something that will viscerally affect us so much—like a great piece of artwork—and we’ll be surprised to learn that it was actually created not by a human, but by a machine?

Miller: Very much so, yeah. In the course I lecture on, sometimes I play the Bach game. You play two short excerpts of Baroque music. One was written by Bach, the other was created by an algorithm. You ask the audience, “Which one was written by Bach?” and fifty percent of them always get it wrong. You play with them a bit and you say, “Well, I’m sure you chose the other option because it was somewhat melodious, somewhat beautiful, somewhat inspirational—just like Bach’s music. But it was written by a machine! How did Bach do it? Can a machine write music of that quality?” But that’s the wrong question, because we want machines to go beyond that to produce music of their own. They will blow our minds perhaps, like Bach’s music did. Bach was done by Bach, and I agree with researchers who disagree with placing too much emphasis on these Bach-or-not games where we play with Bach in my lecture. Some lecturers do the same with art. That’s the point. We should not judge the work of an AI based on whether it can be distinguished from work done by us, because what’s the point? We want AIs to produce work that we presently can’t even imagine, that may seem to us meaningless and even nonsensical, but may be better than what we can produce.

Mason: Could it be the case that AI artists aren’t there for our amusement, aren’t there to blow human minds? In actual fact, they may create something which is uncomfortable to listen to, something that viscerally makes us sick or disturbed or disgusted. In actual fact could that be the paragon of AI art and it’s just something that human beings just don’t find very appealing?

Miller: Look at the music of Stravinsky. It was a long move from Mozart to the Sex Pistols. That sort of music makes some people sick. Even Beethoven’s Third Symphony—people were very disturbed with that. That’s truly a value judgement.

Mason: Will AI choose to create something that cannot be observed, cannot be appreciated, cannot be read, cannot be seen, cannot be listened to?

Miller: By us, you mean?

Mason: By human beings and their human senses?

Miller: That’s right, they’ll all write music for themselves and for their brethren.

Mason: Will we even know if it’s happening?

Miller: Well no, we won’t be able to judge their music. They’ll be able to judge our music, but maybe by that time again humans will be changing, and we may be in such a position that we can hear the frequencies that dogs hear.

Mason: Until we become enhanced I guess now we just have to sit and wait, and see what happens with the future of this machine artwork.

Miller: And see how we are transformed as well. We will be transforming along with how machines produce art. These techniques will change.

Mason: On that note, Arthur, thank you for your time.

Miller: Thank you.

Mason: Thank you to Arthur, for sharing his vision for how artwork might be created in the near future. You can find out more by purchasing his book, The Artist in the Machine: The World of AI-Powered Creativity—available now.

If you like what you’ve heard, then you can subscribe for our latest episode. Or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram: @FUTURESPodcast.

More episodes, transcripts and show notes can be found at Futures Podcast dot net.

Thank you for listening to the Futures Podcast.

Further Reference

Episode page, with introductory and production notes. Transcript originally by Beth Colquhoun, republished with permission (modified).