So I want to say here that I have long, long— I don’t know how long we know each other… Seventy-five years, a hundred twenty, I don’t know but it feels like a very long time. [laughs] Thirty, that is amazing, actually. I have always really admired how you mix in a very substantive way the technical aspect and then these social questions. And I really love the program that you have developed here and the plan, so I just wanted to say that, and your talk.

Now I want to talk, then, just for twenty minutes about this subject, that it is a mistake to think that finance is about money. If it only were, that would be so simple. So I liked what you said before, you know, the monetizing of, and that in a way finance has ironically enabled in massive ways the monetizing of everything. But it itself, if you reduce it to money you’re missing the key aspect of the plot.

So I sort of want to throw out the notion that finance is a capability. And so when you look at some of the measures of its value today, for instance outstanding derivatives, a basic measure—a quadrillion…that money doesn’t exist, you know. Global GDP is something like sixty trillion. There is no— Quadrillion is many many zeros. I know that in Europe you have different designations. It’s more zeros than you’re used to in your average figures that you see with lots of zeros—it’s more than a trillion, let’s put it that way.

So I think one first step is to distinguish between traditional banking, which sells money it has (or it can borrow very quickly, whatever) and finance, which sells something it does not have. And in that selling what it does not have lies its creativity. It has to invent instruments. And secondly—and they go together—it has to invade other sectors. Because it itself does not have what it needs to produce.

Now, of course we use money measures because that’s a way in which we can get some sort of grasp on it. And of course money is made. I mean, that’s no doubt. But finance itself, really, I think it’s extremely important to be thought of as a capability.

Now I clearly am not thinking of capability as a necessarily benign condition like Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum, where capability’s always beautiful and good. You know, I think in a way capability is a variable, and what might be good Time 1 might not be so great Time 2. So when I say capability I mean something whose valence can change radically. Big footnote.

Finance makes capital. So if we could only govern finance, it might actually be rather interesting. We could build housing for the whole world. We could have green transport systems everywhere, etc. So I am not in principle against making a means within this kind of economy that we have now. Ideally we would move to a very different type of economy. But we could actually do some good. But to a very large extent, finance has lost the capacity to govern itself. So it keeps going into crises, and it keeps developing instruments after instruments on itself.

Now, one image that I have is that finance is the steam engine of our epoch. Its present everywhere, directly or indirectly. Now the steam engine was in some ways a more benign innovation than this is.

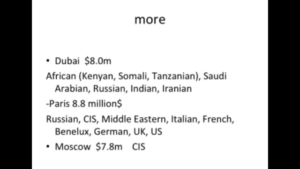

So, I just want to use this as a—this is a very well-known graph—just as an illustration of— So, just very quickly, this is credit default swaps, one kind of instrument. But just look at the rate of growth. That is what I mean by capability. So, it starts under $1 trillion in 2001, and by 2007 it’s $62 trillion. Now that’s more at that point than global GDP, which is $54 trillion at that [time]. Now think of anything that can have that rate of growth. That’s a scale of—you know, that orders of magnitude are jumped. Now if you then consider that right now the value for this particular instrument that we’re dealing over a quadrillion, then you can imagine the rates of growth in all kinds of instruments.

Now, in principle good things could be made with all of this if you materialize it, you bring it down to ground level, you make something out of it. But that mostly does not happen. And when you use ground-level stuff, it often is very destructive. I’m sure again you are familiar with this. So one issue that I have focused on at great lengths is this question of when modest neighborhoods become part of global finance. Insofar as finance needs to invade other sectors in order to deliver goods to itself, it runs out of stuff. So right now we are on student loans, we are on modest homes, because a lot of stuff has been financialized—very high-value items have been financialized, valuable real estate etc.

And here the brilliance, if you want… And here I’m thinking more like you know the famous little book The Technical Problem? Brilliant minds put to work on a technical problem. That might have devastating consequences. But they’re brilliant minds working on…a technical problem. So the challenge in this particular instrument, subprime mortgage by the way is also spreading to Europe. You know we all have a lot of foreclosures in Europe also. The challenge was to delink—and this happens regularly; this is a very good example because we’re dealing with a very concrete thing—a modest little house that can generate for the high-level circuit—investment circuit—an asset-backed security. Actual material good at a time when almost everything has lost an actual material asset.

The challenge, then, since that is such a low-value little thingy, was to delink. To delink the contract that could be used in complicated ways and complicated instruments for the high-level investment sector. To delink that from the actual value of the house. And this made it dangerous for the people who were involved. Because whether they paid or didn’t pay, whether they could or could not pay those mortgages, it didn’t matter.

So I don’t know if people are following me at this point, right. But it took like fifteen or sixteen steps, and I like to say the math of this kind of instrument-making, very complex etc., is not the math of microeconomics. Microeconomics functions in a closed space. This is the math of physicists, those who try to track what cannot be known. So math becomes a very powerful instrument to create some possibility. And that is what finance is—a possibility. Very often it goes wrong, very often it goes very well.

Now, the result of this very short brutal history— This is another thing, an acceleration. And that is enabled by digital technology, by interconnected markets which make it on the one hand unpredictable, on the other hand create extraordinary multiplier effects. So you stand back and if you wanted to give a different term, you would say finance is transactivity, accelerated transactivity that goes in multiple directions and has multiple intersections. Transaction, transaction, transaction, connection, connection.

Am I speaking too fast? Okay, fine. Because I have an accent in English but that might help, actually. The Brits tend to mumble. I don’t know if there are any Brits here in the room, but I can’t understand them, either. But anyhow.

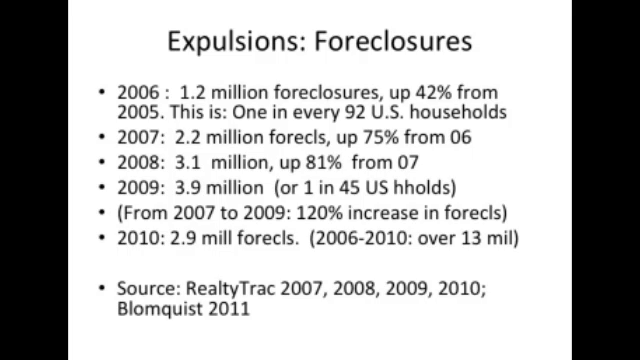

So here get a sense— Now, this is the United States. It’s a very large country; too big, in my book. It should really be divided into several countries. And so these numbers are actually a little little part of the of all the households. But in themselves, it is quite a story, you know. On that scale, those modest houses etc. So, foreclosure is not necessarily that you’re out of your house. But according to our central bank, called the Fed usually, we have right now 9.2 million people in this history of about six years have been thrown out of their homes. That’s an amazingly, sort of…you know, that’s production, I would say.

Now, we have over thirteen million foreclosures. The worst years are 2013, 2014; it sort of dribbles to an end in 2015 because those contracts were issued like say, you don’t have to pay anything for five years because what they paid or didn’t pay, the value of the house, the value of the mortgage, none of that matters. And that again I repeat is the brilliance.

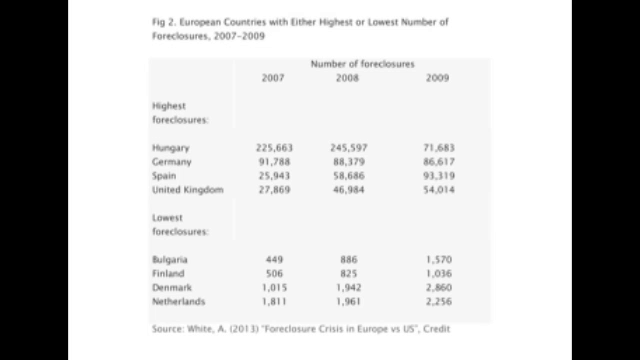

Now, here we have…I have in my new little book that I have gently called Expulsions that deals with some of this and much else— I looked at the Europe 27. And so the highest foreclosure levels— And these are just numbers, and the numbers are much smaller than in the United States, but the populations— So Hungary has now a million households plus that are basically in foreclosure and must be thrown out. But also Germany. I like to mention that. And the Netherlands, see there at the bottom, that is among the lowest. But these economies which still are so much more humane, if you want, than the American economy, they also have this brutal mode that is expelling at the bottom creating an invisible zone truly of expulsions, people who are expelled. It’s not simply a question of exclusion and more inequality. It is deeper. So here you have some of these numbers. I want to move on.

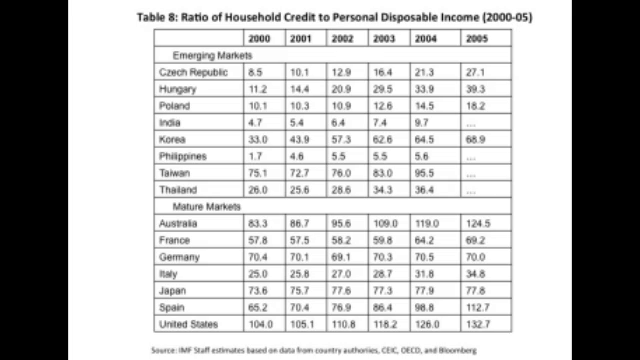

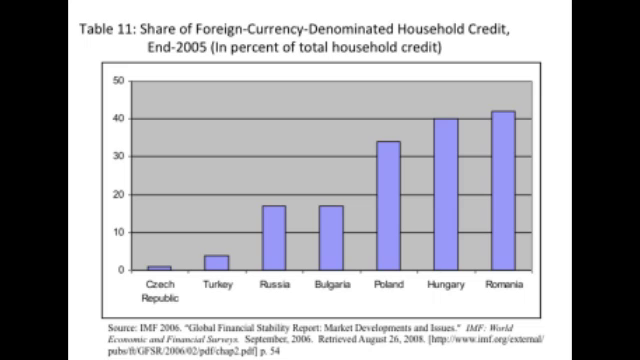

Now, debt. You mentioned it. Debt is the little bridge that helps finance invade just about any sector. And what I wanted to point out—you don’t have to look at everything, but just let’s take Hungary. And by the way the title of this table “ratio of household credit to personal disposable income.” Credit sounds really pretty. Credit is debt. They call it credit, but it’s debt. So what we’re looking at here is another very short brutal history 2000 to 2005. And a lot of the 2000s marked sort of I would say this shift into a truly brutal deployment of this capability. Enormous complexity producing simple brutalities. I find that contrast sort of very compelling.

So look at Hungary. Starts 11%, so reasonable. Look. At that time the United States was already a 104%. Always number one and well over a hundred, right. Now by 2005, that household debt is almost 40%. By then the United States is 132%. Look at Spain, also. Now look at Germany. I love this moment. Seventy, seventy, seventy, seventy. Absolutely they didn’t budge. How they did that I don’t know.

Now, I then I ask myself, because I think it matters, once you look at debt as a critical instrumentality, as a bridge, it’s not just about the debt itself. Who owns this debt? And so you go scrambling in the IMF papers, etc. This is IMF data, basically. And you see that, in the case back to Hungary, for instance, 40% of that debt is foreign-owned. Foreign banks. Now, if a little bank owns your debt, chances are that whatever you pay, the interest whatever it might be, that recirculates. But if a foreign bank owns it, who knows where it goes? And that is of course the story also in the United States, where up to 70% of consumer debt is owned by five big banks. That is absolutely not necessary. The system has destroyed over ten thousand small banks in the last fifteen years. That’s also an achievement, you know. These are massive destructions all over the place. Capability; you cannot think finance in terms of money. It is sort of to me a different…

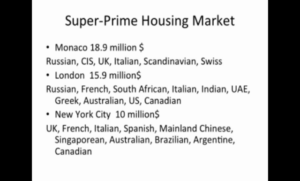

Now, at the same time—I don’t want to dwell on this—there is this new invented housing market. What I want to capture here is something very specific. These are minimum prices. And those are the main nationalities, etc. I just want to run through it as you can see…mixes: Dubai a very different set of nationalities, etc.

I love this one. In Shanghai, the main buyers are Hong Kong, Taiwan, US, Canadian, Korean, like the world is buying in Shanghai. In Hong Kong, much more expensive market, the main buyers are mainland Chinese. I don’t know, I love that. I don’t know if people get it but anyhow.

So the actual de facto price on all of this is a hundred million. It’s just like a flat— The Honda is like the basic ten pounds or the ten this—it’s a hundred million. In New York and in any of these places. None of those buildings is worth that money, none of them. And we’re talking mostly actually apartment buildings.

But we’re also talking a lot of cities like London and Paris, a lot of buildings. And so what I see here, this is not about housing. This is about a land grab, an urban land grab like you have a land grab in the Global South. And how do you buy urban land? You buy it in the form of buildings. And so if you juxtapose that—I think I have a slide later on on the Global South land grabs—2006 to 2010, short brutal history, 220 million hectares of land— And we’re only [counting]—this is the global network Land Matrix getting all the data, etc. And these are only properties that are over two hundred hectares. The smaller is not counted.

So you have this— Some of you may know this, but I’m really very interested in the category “territory.” This is not to do with finance now for a second here. And I think of territory as this complex making of logics of power and logics of claim-making, etc. So this urban land grab and this rural land grab in the Global South, to me it’s very significant. It really downgrades a complex condition that we make collectively and that cannot be flattened into just land or terrain. Flattening it into just a simple commodity that we call land. Anyhow, it is a bit of another story.

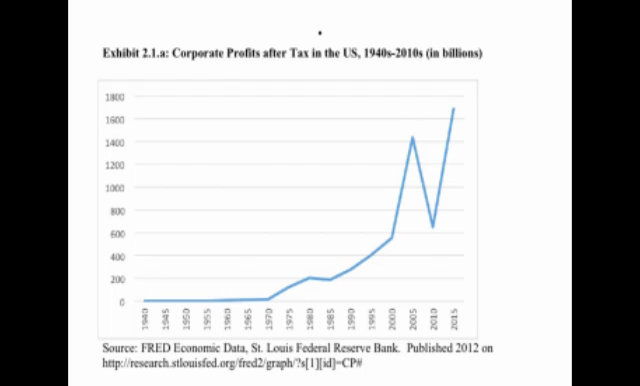

So I just wanted to show you, just to just to nail it down, a few curves; they all go up. They all go up. And what you see here bobbing, this is corporate profits after tax. I’m taking the United States 1940s to 2010s. And it sort of bobs around around—it’s not at zero by the way, it’s just a bit above zero—but this is in billions. And then it starts to go up, and look at 2000 it goes sharply up, then comes the crisis. A crisis that lasts for about two hours, you know—I exaggerate, more like two years. And then it goes up even further. Now, finance is out of the crisis. We are all still stuck in it—or not not all of us but many of us.

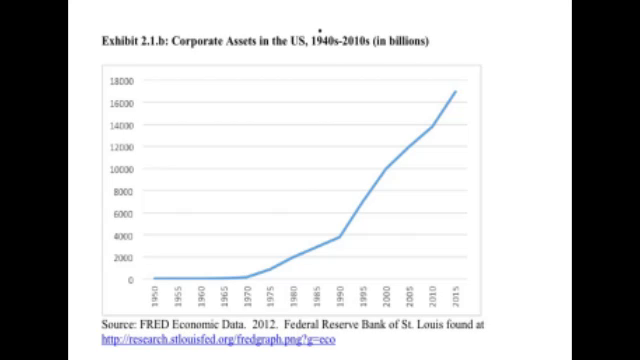

Here’s another one, corporate assets; Same kind of curve. So in this little book— I love these simple lines, a line that tells a tale. Because it has such a sharp change, you know. So you have a lot of these curves that go up, and they start all to go up in the 1980s and sharply really in the end of the 1990s, etc. In this case it’s corporate assets.

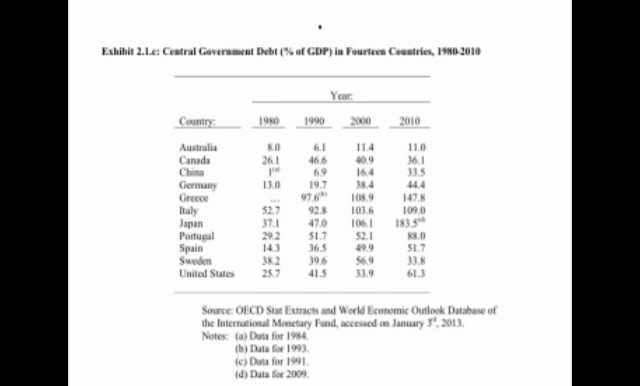

Now, at the same time, countries including Germany—I point [out] Germany because Germany’s sort of trotted out like they knew how to avoid the whatever. All our governments are getting poorer. Most of these governments, functioning liberal states, could not engage today in the kind of vast infrastructure rebuilding, etc. that they did in much of the 20th century. They really have become poorer. And at the same time you see these other curves going up.

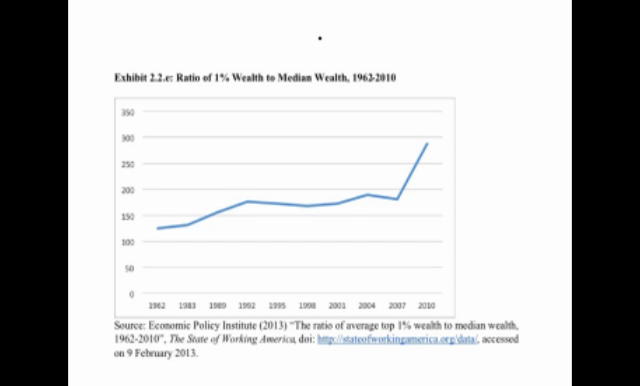

Now here is another curve. This is wealth, and everything you see that of course the ratio of 1% wealth to median wealth, that always was a big gap, etc. But look at the curve in 2007, etc. Whoop, it goes up like that.

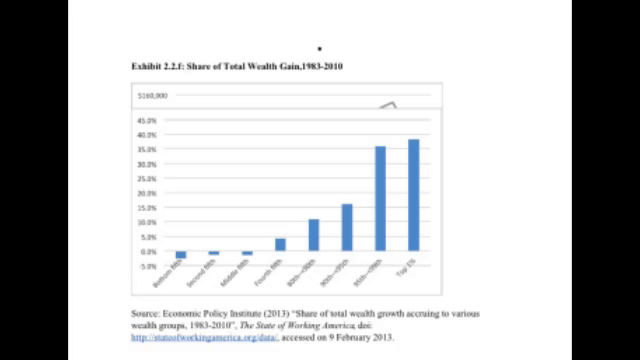

Here is another version of that, share of total wealth gain. What gains is from 80% up, basically. And the rest is losing. These are short, brutal histories that cannot be reduced to this financial crisis bit. I think that in a way one way of putting it is that we’re dealing with an emergent epoch that begins to develop in certain parts in the 80s, etc. And that it has a different DNA. Now, if you think of our DNA, what are we, 88% the same as certain monkeys, right? We humans. But that little 2% actually makes a lot of difference. So a lot of this stuff is absolutely the same as it was maybe in some cases even two hundred years ago. But at the same time there is a little thing that really matters and that gets you on sort of, if you want, the other side of the curve. And so I’m very interested in these curves.

Now, another quick element that I wanted to—because this is another way in which finance has innovated and is a capability. So, there is an agreement in the interstate system, which is one version of what we might call “the world,” with its rules and laws. And that is that you do not take sovereign—sovereign is the state in the language of international law; it doesn’t have to be a queen. So, you do not take a sovereign—a state—to court to demand it…you just don’t do it—in a domestic court.

Well, the vulture funds—who are now proud to call themselves “vulture funds”—in other words they will extract value from little pickings like little modest homes—they did. And here is just an example, just to show again this notion of finance as capability. These financial firms, very aggressive, very innovative, altered the position of the state and sued them in civil court.

And this Elliot Fund is one of the first to be so aggressive and go to states. In October 1995, a New York vulture fund bought $28.7 million of Panama debt for a discounted price of $17 million. Why? Because the banks who owned that debt thought they would never get the money back, since you don’t go and sue a state.

Then they brought suit in a US court—in a domestic court—against the Panama government for full payment of the debt, plus interest. And they got the court to approve—an absolute precedent; we had never seen that—and forced [Panama] to pay $57 million. Now, they did that—I have a full list—with country after country after country. They actually managed to reposition the state and to use the debt vector of banks who are part of the big international system who would not sue a bank, bring it into another financial circuit, and go claim the money.

Now, I know I have to end here, so I’m going to skip all of these wonderful things. […] So… Bye bye. Thank you very much.

Further Reference

Overview post at the Institute of Network Cultures site about the conference panel this presentation was part of.