Silvia Lindtner: Hello everyone. I’m super delighted and honored to be here today. My name is Silvia Lindtner. As you might guess from my name I’m actually born and raised in Austria, but I currently live in the United States, an assistant professor at University of Michigan School of Information and Art & Design. And today, as Michael was already saying, I’ll be talking something that you might’ve heard of more recently, that many people have begun stipulating that we live in something called an age of the maker movement.

So what is the maker movement? Many people, when they think about making, they think about spaces like the following. This is a photo of a makerspace in China. It’s actually China’s first makerspace. It opened up its doors in Shanghai in 2010. And a makerspace, as you might have guessed from the name is a space where people come together to make things. They share the tools and machines to do so, and they tinker together and make things including, for example, experiments in robotics.

This is a swarm robot that the team of the Shanghai makerspace built 2011 and that they submitted to a competition where they won second place, couched between Harvard and MIT. But people also make other things in makerspaces, like for example prototypes of agroponic planting or interactive urban designs. And many times, people who go and hang out in makerspaces, they also present their work at Maker Faires like the one in Berlin, for example.

Many people when they think about the maker movement, they think about this particular device. This is the Arduino. It’s a microcontroller platform that came out of a collaboration at the Ivrea design school around 2006. And this is the device really that is today often named as sort of the quintessential device that enabled the rise of a global maker movement. What it allows you to do in a nutshell is to tinker with hardware. So it allows you to tinker with hardware, especially if you don’t have a degree in engineering or computer science. So it was basically a tool designed for designers, for artists, and anyone else who doesn’t necessarily have a training in electronic engineering. And this really helped proliferate ideas and practices of making, this tiny device that fits into the palm of your hand.

So, what I’ve shown you so far are basically different examples of what people have begun to associate with a promise of making. So, much of when people are excited about making, they think of making as presenting them with the tools and methods to intervene in established structures, be they societal structures or technological structures. So the idea of the maker movement is really to give people the tools and to empower them to intervene in for example corporate monopolies. So rather than buying the latest iPhone, you would be empowered to build your own phones. That’s sort of the fundamental promise and idea behind making.

This goes back to makers sort of positioning their work as a sort of revival of the earlier 1960s and 70s Internet and hacker counterculture of California. It also includes making being seen as a form of novel engagement with new materials. So on the screen here is the LilyPad, that allows you to hack fabrics.

And making is also associated with providing new ways of challenging established gender norms. This is for example a photo of a feminist hackerspace in Vienna. But making has also received much broader attend. This is a photo of the Maker Faire that was hosted at the White House under the Obama administration. So making is also being celebrated as a way to reinvent national identity, and in this case bring back “Made in America,” as Obama so famously put it.

But making has also been associated with re-envisioning citizenship and empowering citizens in new ways. And all of this, what I’ve shown you so far, really comes down to two things. Making took rise at a moment when, especially in Europe and the United States, people began to talk about and critique the rise of precarious work and labor. Not only for people working in let’s say factories, but also the rise of precarious working conditions for people in the creative industries.

So making took rise at a moment when people began— Not just scholars but also media—public media and people working in the tech industry—began critiquing earlier visions and ideas of the knowledge economy and saying the knowledge economy, or ideas like the creative class as propagated by Richard Florida, were sharply critiqued because they did not deliver what they had originally promised. So the promise of making, and the ideas people began to associate with making really took rise at this moment of a broader critique of established structures, including neoliberal governance and precarious work. So that was the first thing.

The second thing is that this promise of making that I’ve already told you about was really couched in a way to provide people the means to intervene in the pitfalls of this information society. And as you can see on the screen, there’s just these various examples of people in making challenging who gets to do technology innovation. That this was maybe something only for men. Or that the notion here was really that everyone can do it, so the slogan of the Maker Faire, for example, is “everyone can be a maker.” So that is sort of the promise of making, that it provides the concrete tools and methods to intervene.

But then we might stop and hesitate here for a second and ask whose empowerment is this? So even on the one hand, we see how women in the maker scene have really challenged established gender norms in the tech industry. And making has also provided an opportunity for politicians and everyday citizens to engage with one another. But on the other hand, we still see how many makerspaces are largely male-dominated. How most of the people who end up being celebrated at Make Magazine are dads with their sons tinkering with robotics and so on.

So even though making is couched as a promise to intervene in established structures, it is still a fairly exclusive project that continues exclusions that have actually also happened before. So there’s kind of a contradiction there, right? On the one hand there’s this vision that is very very powerful, to intervene in established structures. And on the other hand the reality and practice often looks very very different.

So what I want to do today is basically look at a maker culture that isn’t as well known as the one I’ve just shown you. So what you see on the screen are really very familiar models of creative practice when you’re sitting somewhere in Europe or the United States. So it’s kind of a Western view of making. And I want to show you today an alternative to how we can think about creative production and technology practice, and making in particular. And to do so I want to take you to a city in the south of China. Can I get somebody in the to audience tell me where this particular place is, or what the city is?

So this is the city of Shenzhen. You might not see very clearly, but here is a map and this is Hong Kong, and the city of Shenzhen is just north of Hong Kong. And I’m talking about Shenzhen because I’ve conducted research in China—mostly ethnographic—over the last seven years. And this research in China started out with me spending a lot of time in the early hacker and maker makers in China, but then took me in 2012 to the city of Shenzhen. At that time a lot of attention suddenly moved to Shenzhen, especially in the maker scene and the maker movement in China.

So, to most people Shenzhen is known—if it is known at all—through images like this. This is a photo of the Taiwanese contract manufacturer Foxconn that produces for example for companies like Apple and HP. So Shenzhen is the place where more than 90% of our electronic devices have been designed and made. So the Apple phone in your pocket or the computer in front of you was made there.

But more recently, another image of Shenzhen began taking shape. This is a screenshot of a 2015 Wired documentary that came out of the UK. And you might see the headline here. So Shenzhen, the city that was largely known as the site of production and cheap labor is now celebrated as the Silicon Valley of hardware.

So we might want to ask what happened here. And in order to understand what happened in this sort of transition from people not knowing Shenzhen or just knowing it as a site of cheap labor towards a Silicon Valley for hardware, we have to go back about thirty years ago. The kind of city we know today, Shenzhen as a twenty-two-people [sic] metropolis that produces all our iPhones and other devices was a very very different place thirty years ago. It was mostly agriculture, but it was declared in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping as an experiment.

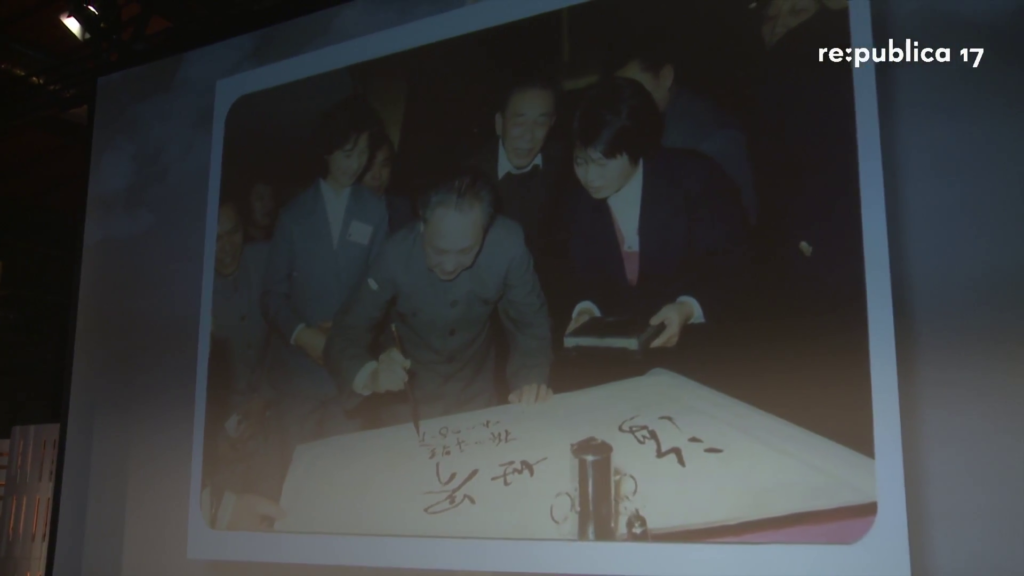

So this region (you can see Deng Xiaoping here) was meant to help China transition or experiment with the transition of opening reforms, and experimenting with a mode of capitalism and what that would mean for China. So this is what happened in the 80s. China began opening up towards foreign direct investment through Shenzhen. This began with investment from Hong Kong and Taiwan first, and later during the outsourcing boom in Europe and the United States also attracted investors from the West. And so to say, the model was a success and capitalism expanded to the rest of China.

So what happened in the years to follow was really expansion of the manufacturing industry in the south of China. This was in the 1990s, basically, with the expansion of original design manufacturing and large contract manufacturing. The best-known example that’s probably familiar to most of you is the HTC phone which was basically a phone brand that was owned by the manufacturer themselves. So the first time an original design manufacturing process that took shape in Shenzhen.

But what is less well-known about what happened in Shenzhen at the same time as large contract manufacturing grew in size is a culture of informal production, an entrepreneurial culture applied to manufacturing. This culture is very often referred to in Chinese as “shanzhai.” Shanzhai translates into English something like “mountain fortress,” and has a little bit of a Robin Hood flavor to it. So when people think about shanzhai, they often think about these stories of 108 rebels who were hiding in the mountains and taking from the emperor and giving to the poor. So it’s kind of like a Robin Hood spirit of sophisticated rebels who basically intervene in the establishment.

So this term began being applied to an informal production culture that began growing as these large contract manufacturers began producing for Apple and so on. So, how you can think about this is this all began in Hong Kong when family-owned businesses started to produce copycat retail like the following. Like the copycat Nike shoe and the copycat Gucci bag. These factories migrated to Shenzhen with the rise of electronic production. And some of those items were produced in Shenzhen in a similar kind of spirit.

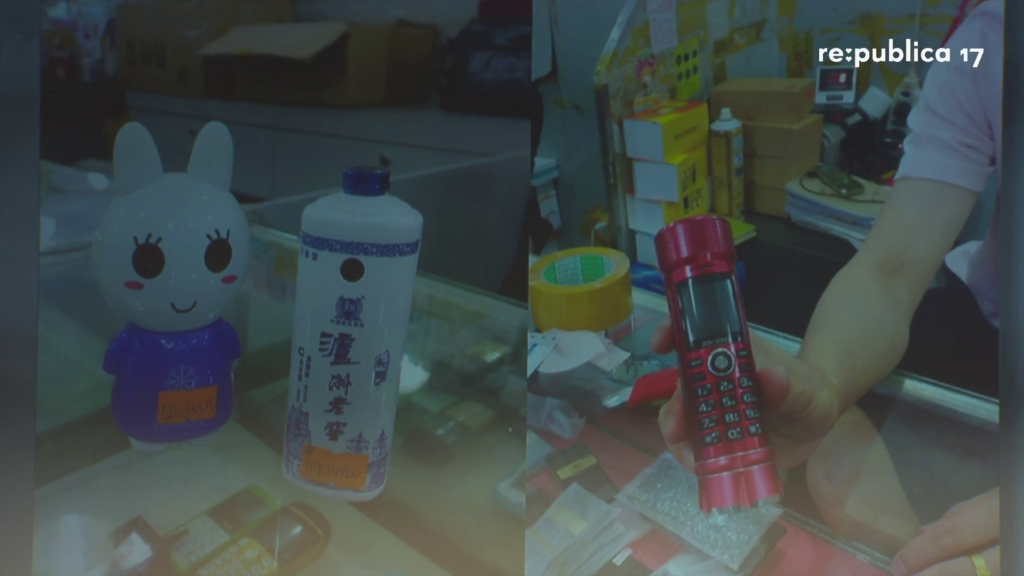

What you see on the screen are actually mobile phones. These are feature phones that come in unique shapes and sizes. And the idea here, that these entrepreneurs in manufacturing had was that there was a gap in the global economy as large-scale contract manufacturers were producing for Apple and Nokia, nobody was catering for niche markets of people who couldn’t afford necessarily a cool phone. So these phones were basically designed for migrant communities, migrant workers who could otherwise not have access to another phone.

And this later expanded to new kinds of creation. You can see here on the screen for example a phone on the right that’s also at the same time a radio and a flashlight. Or the one on the left, shaped like a Chinese alcohol bottle.

Or this is my favorite. I found this three years ago in the markets of Shenzhen and the vendor was joking that this was the latest iPhone 6. I bought it.

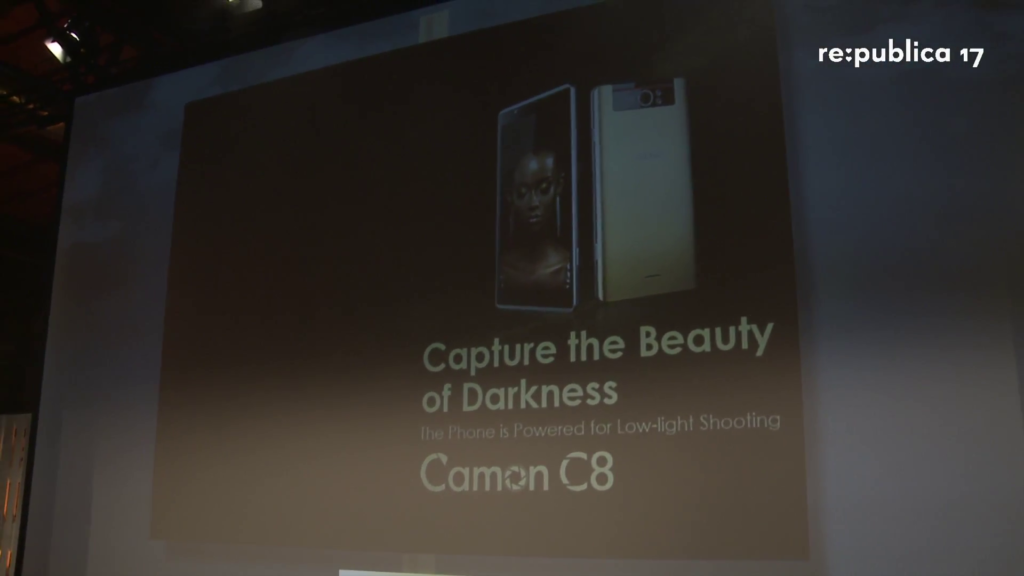

But more recently this informal economy that has built around manufacturing in Shenzhen has also begun partnering with other regions. This for example is a smartphone produced for the African market. Tecno Mobile is now one of the largest phone brands in Africa. And this phone comes with a special feature, as the advertisement here tells as well. It comes (as it says, “capture the beauty of darkness”) equipped with a camera that captures dark-skinned subjects particularly well in low-light conditions. So this is a very affordable smartphone, designed for a very specific market. And this kind of product design came out of this very informal kind of piracy/copycat kind of culture in Shenzhen that is now really a billion-dollar industry.

So I was curious in my research to understand what enabled these entrepreneurs to work in such ways. Like what actually shaped their practice. And what I found was an open source culture that was applied to manufacturing.

What you see on the screen is the board that goes into producing a mobile phone. In this case this is an older feature phone device. And basically this board here, the resources, the bill of material, everything that goes into designing this board is publicly shared amongst the manufacturing and factory entities in Shenzhen. So you can kind of compare this open manufacturing board to the Arduino. It’s basically an open source platform, but applied to mass production, applied to manufacturing.

So they kind of share the same spirit, but one is typically the one on the left—the Arduino board is usually celebrated now as the enabler of the maker movement. As the enabler of new forms of creative practice. As a very cutting-edge innovation kind of piece. Versus very few people know about the board on the right. Most people think about the board on the right as being part of a copycat industry that doesn’t have anything to do with innovation. And why I’m contrasting these two here is to really show you that the reason why we don’t see the the one on the right as innovative has much to do with our own perception of what we think counts as counterculture, of what we think counts as innovation or intervention into the established [status quo].

So basically what the board on the right represents is a kind of intervention that happened through product design. So the shanzhai producer, these informal entrepreneurs and manufacturers, were able to intervene in established structures to say, “It’s not only Apple that can produce products that will be successful in a large-scale market. We can do the same thing with these small-scale entrepreneurs in China who have not really grown in size.”

So, again I wanted to come back to this image of Shenzhen. So, Shenzhen is today celebrated as the Silicon Valley of hardware. And I argue it’s celebrated as such by magazines like Wired not because it is necessarily like Silicon Valley (the one in the United States) but because it’s actually in many ways different and unique. So when people who are active in the maker industry, when they go to Shenzhen these days, they don’t go there because it looks like Silicon Valley, or it acts like Silicon Valley. Because then they could just stay in Silicon Valley. They go there because of this unique shanzhai open manufacturing culture. They go there because they see in shanzhai and in this informal practice a kind of promise to intervene in the structures that they find are harder to intervene in in the United States or in Europe.

So especially what I’ve witnessed over the last year is that a lot of European makers, designers, and artists, as well as American makers, designers, and artists, go to Shenzhen because they see a possibility to intervene exactly because Shenzhen still concentrates the kind of production culture, the kind of messy informal/formal kind of design and manufacturing practices that the West has replaced with the build-up of the knowledge and information economy. And so they kind of see a promise concentrated in Shenzhen’s ability to point to a past that the West so to say has given up.

And so you see this represented in articulations like the following. This is a quote from Joi Ito, the Director of the MIT Media Lab. The MIT Media Lab now has a collaboration with the city of Shenzhen. So they take their students to Shenzhen, mostly the students in engineering, to learn from Shenzhen. And Joi Ito, the Director, went himself and this is what he said after he returned. He said,

What was happening in Shenzhen…they were not making PowerPoints or prototypes. They were fiddling with the manufacturing equipment and innovating right there, on the factory floor… The kids in Shenzhen make new cellphones like kids in Palo Alto make websites. So there is a rainforest of innovation going on. What you thought you could only do with software, they are doing with hardware.

Joi Ito, Want to innovate? Become a “now-ist”, TED 2014 [presentation slide]

And a similar quote from Dale Dougherty, who is one of the key figures in the Western maker movement. He started Make Magazine and Maker Media. He was in Shenzhen in 2014 and I interviewed him when was there, and he was saying the following. He was saying, “I started Maker Faire in Detroit, and one of the events I did the first year I had makers come up and they’d say, ‘Well, I live in the manufacturing capital of America but I can’t get things made.’ ” So part of this is that American manufacturing is geared towards large companies and for smaller entities it’s much harder to get access to them. And then he goes on to explain that Shenzhen is different. Shenzhen is a place that represents where a lot of things get made. So you can still have access to these kinds of infrastructures and production sites there.

I started Maker Faire in Detroit. One of the events I did the first year had makers coming up and they’d say, “I live in the manufacturing capital of America, and I can’t get things made.” Part of it is a lot of American manufacturing is geared towards large companies, and so those interfaces aren’t there for a small company or a small business. Shenzhen is different. It represents a place where they still make lots of things. That expertise is concentrated and detailed there. Not only sourcing parts, but people who know what they’re doing.

Dale Dougherty, Maker Media, April 2014, interview with Lindtner [presentation slide]

And what we see here is that Shenzhen in these articulations of especially Western European and American makers, Shenzhen came to be seen at a moment where people began to really talk about the ramifications of earlier visions of the information society, of the knowledge economy like neoliberal government and precarious work and labor. As people were talking and critiquing these systems in place, they saw promise in Shenzhen because Shenzhen hadn’t yet turned into the same kind of knowledge economy that they had seen on the rise in the West. So Shenzhen became seen, so to say, as an ideal laboratory to prototype alternative futures.

And so I just wanted to return for a moment to where I began my talk. Typically we think about to maker movement as a very hopeful kind of practice that intervenes in existing structures, right? And a lot of that has really in some ways remained an idea and an ideal that I think many of us support. Many of us do believe in the idea that with opening up established structures and exposing how things work from the inside out, we can actually change how people think about the world and how they engage with the world. And basically what happened is a lot of the people who were driven to do this saw Shenzhen as a place where they could actually do that on a larger scale.

So rather than doing it in a makerspace or in a hacker space where the intervention happened perhaps more on a prototypical level or the intervention remained within the kinds of fairly elite practices— You know, if you are in a makers space, most likely you have a higher degree, most likely you’re not a factory worker. So the opportunity that people saw in Shenzhen was that it made them directly engage with the kind of factory work, with the kind of people who produce these devices of which we actually know very little of these days. So Shenzhen in that sense came to be seen as a place where especially people in the West can see a future, can see an alternative that was much much harder to see in established centers like Silicon Valley, for example.

And with this I would like to thank you and take any questions from the audience.

Audience 1: Silvia thank you so much for the talk. It’s really great. And I happen to just come back from Shenzhen not long ago, that when you talk about this alternative future thing that how Shenzhen is rendered as a different image of the different future, what I’d like to know is is this really the alternative future? Because what we do know is it’s still based in China. That there is this governmental kind of interference into the maker scene now, ever since Li Keqiang the Prime Minister has visited the makerspaces and made this a kind of agenda of China ever since 2014. Do you think this would actually change the flavor of Shenzhen from this point onwards? And is this really the alternative future or, also I guess where is the future [?] for Shenzhen specifically?

Silvia Lindtner: So that’s a great question. So what Ding is referring to is that just as the Obama administration was very very supportive of making, and the European Union also has supported maker-related Internet of Things practices, the Chinese government has become really excited about making and has endorsed officially making as part of a new policy called, loosely translated into English, “mass making, mass innovation.” And the idea behind that is that making will enable citizens to become entrepreneurial. So citizens will be empowered to start their own businesses. So it’s a very similar kind of vision to what we see in the United States of what gets politicians excited about making.

So Ding’s question’s about does this kind of political endorsement of making change the very flavor of making? And in some ways it does. What I found fascinating to see in China is that from its inception the maker movement was very much so invested in intervening from within. So a lot of the people who started China’s first makerspaces began actually working with policymakers, began talking to politicians. And this is a strategy and tactic that you see often in China, where political protest and resistance often comes in the nature of a more parasitic kind of engagement where people are rather than outright opposing the system, because that’s really hard to do, they intervene from within and intervene from within these established structures.

And so actually the kinds of terms that the Chinese government is using today for making, the Chinese terms were actually invented by the makers themselves. So you see this really interesting symbiotic, parasitic relationship between citizen and government. And Shenzhen again is an interesting example here. Because Shenzhen as I mentioned in the beginning was really an experiment, right, where the government on the one hand declared top-down that this region should be the place where China’s modernization project has been implemented.

And then there was a lot of top-down urban planning that happened later, but at the same time because Shenzhen is far from Beijing, it’s far from the political center so to say. So Shenzhen was always also at the same time allowed to develop its own informal practice. So you see a kind of illicit experimentation happening in Shenzhen. A kind of formal culture and informal culture mix so there’s this constant dance between control and grassroots activity, and that exists in Shenzhen until today. And this is the very reason I would argue why so many Western makers and hackers find it so intriguing, because it’s this constant play and experimentation in between official and informal culture.

Audience 2: So in the maker movement there are platforms that makers use to share files, share information, Github, Thingiverse… Can you comment at all on what the shanzhai— What are the mechanics of how the shanzhai community exchanges information?

Lindtner: Sure, yeah. That’s great questions. The kinds of sharing practice that are central to shanzhai work through a…I would say very informal network that comprises a mix of both traditional forms of networking—so people going out for dinners, drinking…but also the usage of digital technologies. So there’s a very well-known I would argue, but not well-known in the West, social media app called WeChat that really shapes interaction and also business culture in China these days. So, WeChat is actually one of these platforms where people share in many ways similarly to how we would share in the West as well when we collaborate with one another. So there’s a lot of file sharing and knowledge sharing that happens both offline in these sort of very informal gatherings as well as through the WeChat app.

And then there’s platforms like Taobao and Alibaba that support the kind of trade relationships that basically make shanzhai culture happen. So you can think of this as small-scale entrepreneurship that basically exists online and through which people informally connect as well. Is there a follow-up question?

Audience 2: Yeah. It’s just interesting that you say that because WeChat, if I understand correctly, is more of an exclusive platform; you have to be opted into that, right? So you’d have to be included, whereas anybody can log onto Github and download something. So is that the standard, you have to know someone to get into—

Lindtner: Yeah. It basically goes through your social networks, you have to know somebody— There are other mechanisms in WeChat to broadcast. So there is some really interesting experimentation happening with sort of microblogging and writing that you can actually send out again, but through your network but that proliferates very quickly.

Audience 3: Thank you very much for a very interesting talk. I once heard the former chief economist of the World Bank Justin Lin speak about Shenzhen. And in his opinion it had kind of grown beyond its own— It succeeded so much that it was sort of going to— It couldn’t carry on because the cost of real estate is so high and so on. And in his talk he was saying that he anticipates that a lot of the companies that are there are going to have to move out to new markets and so on. And he thinks Africa might be a very good place for some of those companies to go. Could you comment on this, and do you see this happening?

Lindtner: Yeah. So thank you for that question. So the question of how Shenzhen partners with Africa is a really interesting one. You might have heard the Chinese government has a new policy called One Belt One Road which is basically an expansion of the Silk Road that takes you all the way to Africa. And in part, this is an expansion of infrastructural building expanding China’s capacity to build roads and infrastructures and cities.

But while this is kind of top-down, at the same time what I’ve seen emerge in Shenzhen over several years now are partnerships that happen more on the entrepreneur level where for example some people in manufacturing who I’ve followed for many years are now partnering with people in Ethiopia to set up manufacturing sites there. So this is happening really on the grassroots kind of level where individuals are struggling with some of the economic changes in China and are sort of seeking new markets. And this is largely happening through partnerships between entrepreneurs.

So these are not the kind of entrepreneurs that usually are the kind of Silicon Valley, venture capitalist-funded kind of ventures. But these are entrepreneurs who work through getting loans from the bank and these kind of informal entrepreneurship networks where people meet up for drinks and so on. And that’s now happening increasingly so interculturally, and so I anticipate there will be way more happening in these kinds of trans-regional networks between Africa and the south of China.

Audience 4: Great talk, thanks for that. You said that the companies kind of openly share the designs for the devices. Is there any legal framework for that, or do they do that liberally?

Lindtner: So as I said, these sharing practices are coming out of really informal economy practices. So there is in that sense no legal structure around that. So I would say in many ways this unfolds through a kind of gray you know, half-legal, some of it is legal, but not all of it, a kind of gray zone of experimentation which allows actually a lot of this tinkering on a mass scale to happen.

And so again, a lot of the people who are committed to open source sharing and rethinking the kind of legal structures that are in place that usually protect the large corporations, they are drawn to that because they’re saying okay, this is a kind of model that could perhaps also lead or provide insights for the kind of open sharing practices we do elsewhere. But yeah, there’s no formalized structure on it, which is exactly what allows it to happen, basically.

Audience 5: Thanks for your talk. It was very informative. I would like your opinion about how do you view these developments in Shenzhen? Do you think the people that let’s say will ultimately benefit a lot? Because right now we see these horrible working conditions and that. Do you think this maker movement will change that for the better?

Lindtner: So for that we really have to see what has already happened in Shenzhen over the last twenty years. I would say now there’s a lot of attention towards Shenzhen as this kind of new place. But I think the biggest transformation that’s happened in Shenzhen really was sort of in the 2000s, you know, especially when there was a lot of opportunity in manufacturing, a lot of migrant workers, and people really coming to Shenzhen to make themselves, to make a better living for themselves, and for their families back home. And that was always something that wasn’t available for everyone. And there’s a gendered aspects to that as well. It was also very often available for young men who tried to remake themselves.

So I think when we look at Shenzhen today there’s this really fascinating blend happening of a younger generation who grew up in Shenzhen. So there’s now a first generation of Shenzheners, right, of people who really sort of identify with the city. And there’s a lot of wealth that grew over the years in that city. So I think we will see the continuation of both happening. There will be more opportunities. There will be the continuous problem, as much as it is in the West, of who gets these opportunities. Like whose innovation is this, in many ways. Who really has access to these structures.

And so I think it will be a continues kind of struggle, especially for people who aren’t especially by the Chinese government considered these kinds of entrepreneurial citizens that they now want to really proliferate across the country.