Ingrid Burrington: So yeah. The title of this talk is “Everybody Runs.” So, I am an artist and writer. This year I’ve kind of been operating more I guess in a curatorial mode, more than kind of making a lot of new work. And this is partly because I’ve spent a lot of time being paralyzed by crippling anxiety and depression that makes it really hard show up for myself. But another reason that I’m going to talk about is that I’ve been thinking a lot about futures, or the end of the world and different ways that people manifest futures and visions of the world and the world to come, and how that shapes the way that we live in the world now and the ways we think about in particular technology.

And…I don’t know. Personally I think it’s kind of more useful to get a bunch of different futures on the table and look at different practices and approaches than be like, “What do I think about this?” right. So a lot of what this is manifested as is kind of doing events and kind of gathering texts and putting people in a room. So this year I was running Data & Society’s speculative fiction reading group, which was a super fun way to get people working on different subjects all together.

This was the title card from a panel I organized for Theorizing the Web called Apocalypse, Buffering, in which I had three of my favorite people, Jade Davis, Damien Williams, and Tim Maughan— (Jade and Tim are here. I’m sad Damien’s somewhere in Atlanta.) But I asked them write speculative dystopian fiction in the form of slide lectures for an academic conference. It was really fun.

And this is a slide from a conference that I hosted here last week called Future Perfect. All of the talks are online. It was really delightful, actually. We got a good group of weirdos in the room. This is from the second panel.

But so one of the reasons that I guess I’ve been doing work like this, I’ve been trying to get as many weird futures on the table as possible is because the truth is there are these sort of ubiquitous futures, right. Ideas about how the world should or will be that have become this sort of mainstream, dominating vernacular that’s primarily kind of about a very white Western masculine vision of the future, and it kind of colonized the ability to think about and imagine technology in the future. This year actually is funny for having a lot of kind of auspicious anniversaries in this genre.

So the iPhone is ten years old. And it’s not technically a work of speculative fiction but I think of it as sort of an object that sort of foreclosed on a certain kind of futurity. This is a real thing that Steve Jobs said when he introduced the world to the iPhone.

Snow Crash is twenty-five years old, Neal Stephenson’s landmark bro sci-fi novel. And while Mark Zuckerberg apparently no longer makes the novel Snow Crash mandatory reading for new Facebook employees, which was something that was written about in 2014, he’s still very happy to cosign on making the Metaverse a reality, with this turgid white supremacist shitposter Luck— Palmer Luckey? Yeah. Horrible man.

Anyway. I only have ten minutes. And I’m at the end, and you guys will probably want to get a drink. So I’m going to talk for the next few minutes about a particular case study of an artifact of the sort of dominant future vernacular whose auspicious sort of anniversary of coming into the world happens to be today.

So on June 21, 2002, fifteen years ago today, Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report was released in theaters and with it, mass media depictions of the future were kind of indelibly transformed. And I don’t really want to talk to you about what Minority Report got right and what it didn’t get right. Because the “Where’s my jet pack?” conversation is not particularly interesting. This is also true, though.

Time Cops, Christopher Beam, Slate;

Big Data and Law Enforcement: Was ‘Minority Report’ Right?, Yaniv Mor, Wired

I think that what I’m more kind of interested in is what made that future desirable? And maybe why it kind of has persisted as something that’s desirable. Like these are just some GIFs from some kind of corporate future concept videos—you can find a lot of these on YouTube—and it remains this kind of point of reference for a lot of corporations and PR flacks while simultaneously for many others being seen as sort of this neoliberal dystopia or bane of a graphic designer’s existence.

So just for some context, how many people are familiar with the film Minority Report? How many people have seen it in the last thirty days? Okay cool, right, yeah. So, anecdotally, and if anyone has an opinion on this please correct me. In my experience of kind of talking to people, especially people who work in the spaces of policy and technology and society who often complain about this film as this kind of knee-jerk referencing of the future, is that while most people can remember kind of the aesthetics and the interfaces and sort of the vibe of the film, there isn’t really a single line of dialogue, or most of the basic plot premise that really completely translates. And this could be because you know, the dialogue includes such gems as, “Look, I’m not with the ACLU on this, Jeff.” Or, “In the milk, all they see is the future.” That’s now my favorite part of it. I can’t believe that’s not a constantly-quoted line.

But I also think there’s something very deliberate about that. Like, the priorities that Spielberg himself put into making this film, and the worldbuilding process that he used, was in some ways very much deliberately about kind of foregrounding aesthetics, foregrounding tech, foregrounding kind of a vision of a technocratic society more than any of the kind of policy concerns. And I think that a lot of these works that are kind of one person’s dystopia and another person’s product roadmap have this quality. They foreground the premise over political economy.

Inside Minority Report‘s ‘Idea Summit,’ Visionaries Saw the Future, Wired Staff, Wired

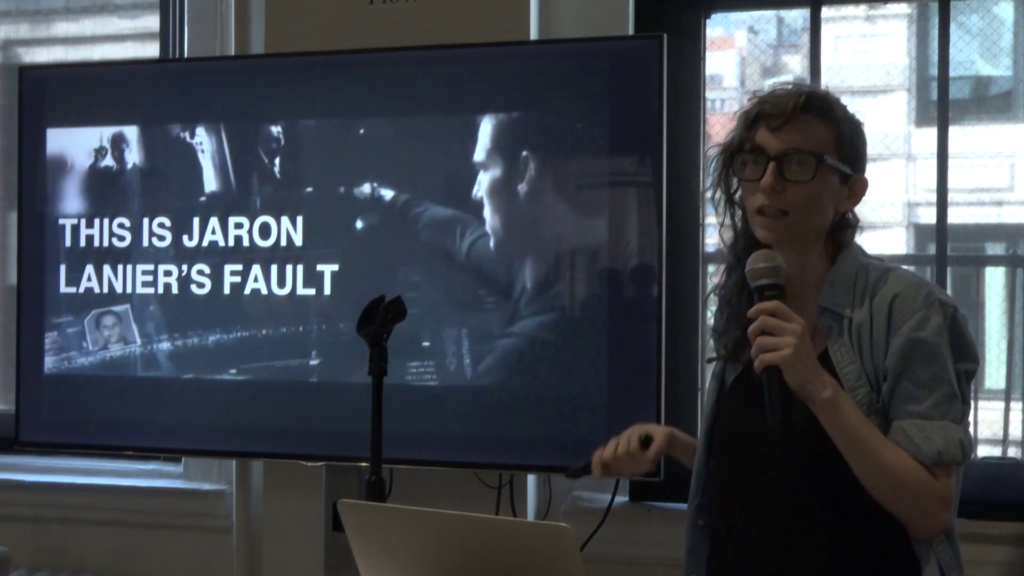

This is from a really good 2012 Wired piece where some journalists went and interviewed all of the consultants who worked on the film. And I don’t know how many people know this story. Back in the day, Steven Spielberg had all these technologists and futurists and people from MIT and stuff into some hotel in Malibu for a weekend and was like, “Tell me what the future’s gonna look like.” And this was people like Stewart Brand and Jaron Lanier. Douglas Coupland was there. It’s kind of a bunch of TED Talk-type guys were all designing the future. And some of this was based on you know, the work that they do as consultants kind of just forecasting what they could imagine based on real technology.

Some of it was blatant product placement. Lanier himself was working on stuff related to the Kinect around the same time. He brought prototypes to the meeting. I also like blaming him for things; maybe it’s unfair.

Steven and I talked specifically about creating a new set of vernacular images of the future. Before then, the only images that anybody ever referred to were either Blade Runner or 2001. It was a very dark vision. Our goal was to get on screen a really amazing vision of the future that people would talk about We achieved that overwhelmingly.

Peter Schwartz [presentation slide]

But this is a quote—I’m not going to read the entire thing to you but I’ll try to get through some of it—from that particular oral history that I think a lot about. You know, “Steven and I talked specifically about creating a new set of vernacular images of the future.” I don’t know why they had such a problem with images of the future looking like Blade Runner. But whatever, that’s your call. But again, the point being like, the amazing vision of the future was kind of more important than necessarily the political implications of it.

Right now, people are willing to give away a lot of their freedoms in order to feel safe. They’re willing to give the F.B.I. and the C.I.A. far-reaching powers to, as George W. Bush often says, root out those individuals who are a danger to our way of living. I am on the president’s side in this instance. I am willing to give up some of my personal freedoms in order to stop 9/11 from ever happening again. But the question is, Where do you draw the line? How much freedom are you willing to give up? That is what this movie is about.

Steven Spielberg, “Spielberg Challenges the Big Fluff of Summer”, New York Times, 6/16/2002 [presentation slide]

And to his credit you know, Spielberg made some kind of statements about this. This is way too long to read you. This is from a 2002 sort of puff piece in advance of the film where he’s talking about the sort of civil liberty implications. But he also says that you know, “I’m on the president’s side in this instance. I’m willing to give up some of my personal freedoms. It’s kind of important to think about the fact this was also the first major summer blockbuster after 9⁄11, right. This is kind of the tone in which this technology is being presented to people.

And I think you know, it’s nice that he’s sort of thinking about it. But ultimately, what ends the precrime program in the film (spoiler alert) isn’t a realization of the gross violations of civil liberties, or just the fact that it’s kind of just a messed up concept. What ends it is that they learned that the head of the precrime program murdered a lady and that he found kind of a flaw in the larger system that was able to let him get away with it. So it’s like a technical shortcoming that means that the system might not always work? That’s what actually ends precrime. It’s not actually a discussion of whether or not it was a good idea.

So again, there’s a lot of energy put into kind of the worldbuilding of the film. But the narrative arc is kind of just a means to an end to that worldbuilding in a lot of ways. And I think there’s a lot of real emotional investment in the parts about Tom Cruise mourning his son. And there’s not a lot of context given to I think what is actually kind of the biggest plot hole of the film. And I apologize in advance because I told you I wasn’t going to say what it got right and what it didn’t. But I do think this is actually kind of relevant.

So the entire like, driving concern of the movie is this shift where the precrime program, which starts as like a DC Metro crime-prevention strategy is going to “go national.” And there’s never an explanation given as to what going national means, because at the end of the day the precrime program is these three children of drug addicts who have had mutations in their brain that made them psychic to see into the future, who can only work together when they float in a pool where all they see is the future.

So are they going to like, have to see everything in the country now? Are there more people like them? Does every city get a pool? This is never explained. And what happens if one of them dies? Like, it’s the most logistically improbable product scaling plan I’ve ever seen.

And again, this is what the film really got right. Because at the end of the day, this is a world in which state of the art technology ultimately depends on and bottoms out in the exploitation and emotional labor of a small group of people who are ultimately already starting at the bottom rung of society, right. They spend their entire lives being sedated through the process of constant exposure to traumatizing images and data in the service, ostensibly, of maintaining the peace but also kind of acting as pawns in the establishment of this kind of super fucked-up world order of perpetual surveillance.

And you know, that’s one way of talking about content moderation. And that’s one way of talking about what the gig economy does to consumers who ride in ride-sharing vehicles. And that’s one way of talking about what it’s like when I open a browser tab. And all of this is kind of to say that what makes kind of cyberpunk, “my dystopia, your product blueprint” futures so enduring is that erasure and undermining of the actual work and pain that goes into building those worlds. These are worlds that are kind of designed to make pain into somebody else’s problem. And I think that the gestures towards what’s fundamentally fucked-up about it in a lot of this kind of dominant cinema and language is just that. It’s a gesture. And ultimately kind of what happens to the rest of society isn’t that important until it makes Tom Cruise, a cop, have a hard day.

And I think trying to own the future through affect, through devices, through aesthetics, with this sort of vague dismissal of, or lack of comprehension of policies, societal structures, and who ultimately kind of bears the burden? Is kind of a piece of a larger, more kind of ominous worldbuilding that I feel like is part of the world we are living in today, right. There’s a longer thing about prepper culture that I was going to talk about but we’re definitely out of time.

Ultimately it’s a vision of the world where everybody runs. “Everybody runs” was the tag line of the film. I think I neglected to mention that. I would’ve been surprised if any of you remembered that detail but yeah, this is a world in which everybody runs from accountability, and from culpability, and from obligation to other human beings. And I honestly can’t think of anything that’s kind of more emblematic of the American Dream, in a weird way. But so… I don’t know. I’m running out of time and I don’t have great answers of what it takes to change or resist these hegemonic features. I mean, currently the recommendations I’ve got are more futures, right. More narratives. More kind of gathering. More discourse. More worlds. More care. More humanity. And probably less white men. Thank you.