Sasha Constaza-Chock: Hi. Thanks. Thanks for having me here, and it’s been a really stimulating day so far. My brain is spinning with all of the different talks and presentations. I’m going to give you a brief overview of design justice, the theory and the community practice. And then I actually am going to use a little bit of my brief ten minutes to actually get us talking to each other a little bit but don’t worry, I will guide you through. It’ll be okay.

So my name is Sasha Costanza-Chock. My pronouns are they/them or she/her, and I’m currently associate professor of civic media at MIT. And I just came back from Barcelona, where I was doing a keynote at the Smart Cities World Expo and Congress, which was sort of a convening of about 170 municipalities and the smart city technology vendors that are trying to get the contracts from them. Now within that, there’s a cluster of about seventy cities that’s called the Sharing Cities Network, and they’re trying to develop alternative or different visions of what it would mean to instrument urban spaces in ways that can support democratic principles, worker-owned cooperatives, alternatives to the current exploitative and extractive so-called sharing economy or the platform economy or the gig economy, or the Uber vultures or the WeWork— I’ll stop.

But so, in this space basically there’s a trade show and people are selling tools for monitoring cities, for city efficiency, for energy efficiency, for traffic efficiency, and for—under the the mark of the managerial neoliberal city manager, basically—how to instrument cities for surveillance capitalism, as Shoshana Zuboff would call it.

But I was most struck as I was wandering through the stalls by this company, that was selling tree systems for urban environments, where you install a tree—and it doesn’t actually have to be connected to the true soil—and it will be fed the amount of water that it needs. It’s linked to Internet of Things sensors so that city managers can have a real-time bird’s eye view of the health of the trees in the urban environment and so on and so forth. And they also talked about additional features that you could add, such as wifi networks and surveillance cameras to the trees. Which if any of you have ever seen— Have any of you seen Sorry to Bother You, has anyone seen this film? You need to see this film. So, sadly you know, fiction imitates life imitates fiction.

And so, this is at the stall. You know, this is an architectural rendering of the smart tree system and this is the actual tree that they brought to the expo. So here we have the sad image of you know, technological solutionist ideas as to how we’re going to create the green city. And I wanted to start with this because we need to understand that the discourse that we’re developing here and using here around Green New Deal is not the only discourse, and that one of the most powerful alternative discourses is the smart city discourse. It’s the idea of the perfect vision from above which we can use to create a green and efficient city. That was more time than I meant to spend on that.

Because really what I want to share is one way of thinking about how we’re going to design and build the technologies and the sociotechnical systems that we need for a Green New Deal, if such a thing is what we do want to build. And what that could look like through the lens of this community of practitioners that I’m part of, which is the Design Justice Network.

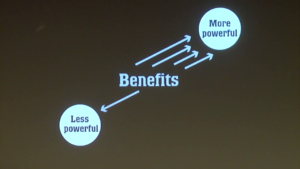

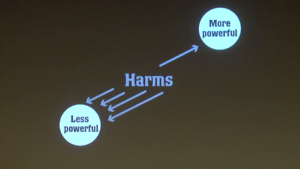

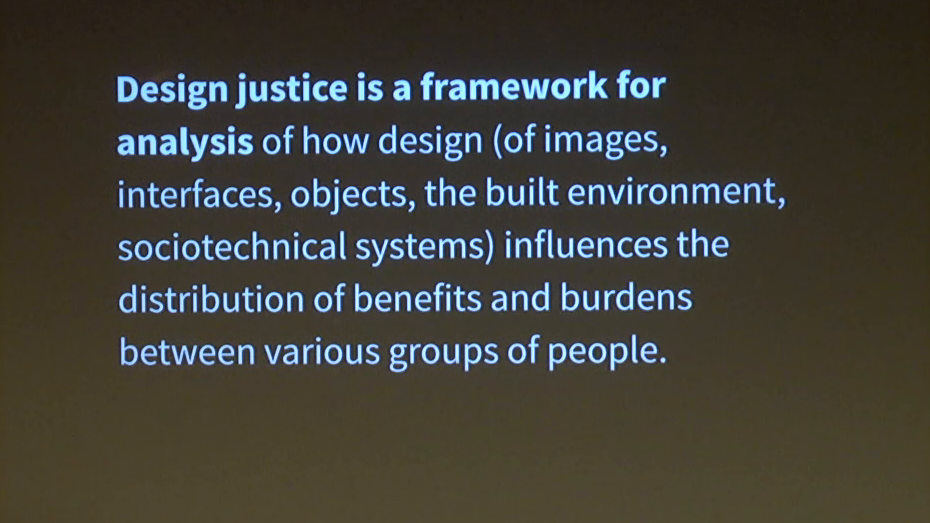

So what is design justice? It’s a framework for analysis of how the design of images, interfaces, objects, the built environment, and sociotechnical systems influences the distribution of benefits and burdens between various groups of people. The distribution of benefits and burdens between various groups of people.

Because currently most design processes allocate most of the benefits to those who are more powerful, and few benefits to those are less powerful. And most of the harms to those who are less powerful, and fewer of the harms to those who are more powerful. So we could see people in Silicon Valley not allowing their children to have access to smartphones and smart devices because they understand the harms that are being done through nudge surveillance capitalism to the young minds of their children and they’re not interested in doing that. Or we can see people in the Bay Area instituting the moratorium on facial recognition software used by police because similarly, people who are designing these systems understand… And actually, I don’t want to frame it that way because this is the result of community organizing efforts, right. But partly it achieves resonance because powerful people with access to the city council understand the way that these harms work.

Design justice is an attempt to push a little bit further than floating ideas around design for social good, or even HCD—human-centered design, participatory design processes, because design justice focuses very explicitly on how design reproduces or challenges what black feminist sociologist Patricia Hill Collins calls the matrix of domination, the interlocking systems of white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, capitalism, and we can add ableism, settler colonialism, and other forms of structural inequality.

And in her classic text Black Feminist Thought, Patricia Hill Collins of course is looking at how each of us occupy positions of both privilege and also less privilege within the interlocking system of the matrix of domination. Each of us, we need to understand the way that we move through the world in particular bodies as structured by these historical forces and the way that that operates both at the individual, the community, and the structural level.

Another way of thinking about this when we think about how are we going to design the built environment, objects, solar panels, urban tree root systems for the Green New Deal is we need to think about who was involved in the design process, who was harmed, and who benefited. And what does that intersection look like.

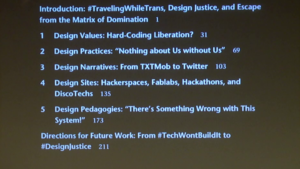

I have a lot more to say about this topic, but I don’t have enough time to talk about it right now, but I do have a book coming out with MIT Press in February called Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need. And it’s structured like this. And I’m not really gonna summarize this, because I want to get a chance to do something together. But these are my attempts to summarize some of what I’ve learned over the past decade or so of doing design practice and working with the Design Justice Network. Because I want to emphasize that this concept is not something that I came up with; it comes out of a community of practice, a growing community that focuses on the equitable distribution of design’s benefits and burdens, more meaningful participation in design decisions, and the recognition of community-based indigenous and diasporic design traditions, knowledge, and practices.

And it’s a network that comes out of the Allied Media Conference in Detroit. Has anyone been to the Allied Media Conference? No, nobody? Wow, I’m a little bit surprised. You should go. It happens every year in Detroit. Actually it’s now going to be happening every other year. It’s been going for about twenty years. And it’s one of the most, to me, important, exciting, and interesting spaces where people at the intersection of cultural work, media production, and design work, and many different social movement networks gather each year to share, to build, to develop new language, new networks, and new ways of creating cultural narratives to shape the possible future worlds that we might want to actually inhabit and that will be ecologically survivable.

So in 2016, a group of thirty architects, graphic designers, interface designers, landscape architects, and community organizers gathered to convene the first Design Justice Network gathering, came up with a set of principles, which we’re going to see in a moment, and sort of grew from then through a series of tracks at Allied Media Conference. The signatories of the principles has now grown to several hundred people. And we just recently launched a formal membership structure. You can find us on the gram. And here’s some recent images. There’s a Design Justice Network Chicago local node meetup happening; I think it happened yesterday. Toronto has a local node.

So in Toronto, the local node is focusing especially on working with housing rights activists and civil liberties activists, and privacy advocates to fight back against Sidewalk Labs, which is Google’s project to create a smart city where… We don’t have time to talk about it; talk to me afterwards about it. But so blocking Sidewalk is one of the main goals of the Design Justice Network node in Toronto.

In Philadelphia there’s a node that started meeting recently. In Barcelona, there’s a group that links together designers from Italy and from Spain who are meeting to think about how they can use designerly practices to challenge the Fortress Europe idea. And local nodes are mushrooming all over the place. So just recently we’ve got New York City Design Justice Node had their first meetup, and so on and so forth.

But with the last couple minutes I did want to get us to think about how can the Design Justice Network become more connected to and involved in the struggle for ecological survivability and the Green New Deal. I do think it’s part of that. And so what I want us to do now, is we’re going to look at the Design Justice Network principles together. There’s ten of them. And we’re gonna read them together as I put each one up on the screen. And whichever one gets read most loudly, I’m then going to do something together with all of you. So, read the one you like the most the loudest.

First, we use design to sustain, heal, and empower our communities, as well as to seek liberation from exploitative and oppressive systems.

Two, we centered the voices of those who are directly impacted by the outcomes of the design process.

We prioritize design’s impact on the community over the intentions of the designer.

We view change as emergent from an accountable, accessible, and collaborative process, rather than as a point at the end of a process.

We see the role of the designer as a facilitator rather than an expert.

We’re halfway there.

We believe that everyone is an expert based on their own lived experience, and we all have unique and brilliant contributions to bring to a design process.

Just in case that didn’t sink in…

We share design knowledge and tools with our communities.

We work towards sustainable, community-led and ‑controlled outcomes.

We work towards non-exploitative solutions that reconnect us to the earth and to each other.

It’s your last chance to go big.

Before seeking new design solutions, we look for what’s already working at the community level. We honor and uplift traditional, indigenous, and local knowledge and practices.

Okay. So, I’m just gonna leave this one up here. And what I’d like you to do now is turn to the person next to you. And if you’re not right next to someone you can turn around in your seat and talk to someone behind you or in front of you. And I’d like us to take just about two minutes, I think I have, to share with each other how might a project that you’ve worked on in your own work, your own designerly practice related to the Green New Deal look different if you focused and centered principle ten. So let’s do that for just the next two minutes.

You have sixty more seconds.

Okay, wiggle your fingers if you can hear me. Wiggle your fingers if you can hear me. Wiggle your fingers…

Awesome. Okay. so I have time just for three, maybe two or three quick popcorns, if anyone wants to share back a key takeaway.

Audience 1: My name is [indistinct] and I’m from Brown University. One of the things that I’ve noticed—I don’t do design. I do [indistinct] studies. But I did an agriculturally—

Constanza-Chock: In a tweet.

Audience 1: In a tweet.

Costanza-Chock: In a tweet.

Audience 1: There are farmers [indistinct] experts where they’ve shifted the discussions, where farmers have to make up 50% of the crowd and the experts can’t talk.

Costanza-Chock: I love it. I love that. Thank you. Someone else? Everyody’s shy now.

Audience 2: Hi. We’re a local solar company, NEC Solar. This applies to changing policy in order to give people what they need from solar, versus giving them a cookie cutter shape to fit into.

Costanza-Chock: Absolutely. And maybe one more burning takeaway.

Audience 3: So we had this design challenge on a property that I worked on where there was too much water. Clay soil, you know, everything was a mud pit. And they paid a fortune for this irrigation system that is overirrigating everything on top of the already soggy [indistinct]. So instead, we designed a cistern to catch the extra water and pump it back into the irrigation system. So instead of using extra water, we’re just collective what we already have and repurposing it to where we need it.

Costanza-Chock: Exactly. Thank you so much for those three examples. You know, we already have so much of what we need. And in the Design Justice Network we’re trying to build a community of practice that recognizes that and advances it.

So you can sign on to these principles at designjusticenetwork.org. And you can also join us for our next network gathering at the Allied Media Conference in Detroit in late June of 2020. And I hope that we have a chance to discuss this a little bit more. But I think my time is up for now. So thank you.

Further Reference

Climate Futures II event page