Jose Antonio Vargas: Oh, comedy. I was laughing my ass off back there. Comedy is so important. If I didn’t laugh about my own circumstance I don’t know where I would be. It’s really nice to be with all of you. Especially, kind of the word “defiance.” I feel like the past six years for me has been all about defiance.

Defiance of the United States government, who especially in the past six months have been deporting and detaining people in record numbers. Three months ago ICE, the Immigration [and] Customs Enforcement reported that they had deported and arrested 42,000 “illegals” in three months. That was the language that Immigration and Customs Enforcement use. That’s a 60% increase from the same time last year.

Defiance against my own lawyers. Especially after the election told me to stop flying around the country and just stay in the great state of California, driving around from San Francisco to LA. They said, “No more getting on planes.” But in the past six years of doing the work that I do, I’ve been walking around like a walking uncomfortable conversation, traveling all across this country. At Define American we’ve done more than 850 events in forty-eight states, including about 200 Republican Tea Party conservative meetings. And visited more than 300 college campuses. I was a political reporter at The Washington Post, and after doing all that traveling, the moment Trump announced his run for President I told all my political reporter friends, “Trump is gonna win this thing.” And they told me I was crazy.

So against the advice of all these lawyers, I’m still traveling around. I’m still “defying.” And my existence in this country in many ways is an act of defiance. I have to say it gets the trolls really really pissed off. Actually just two days ago, this troll who always gets at me every day says, “Clock is ticking and your stay is getting shorter by the day.”

And I tried to kind of calm myself down. And I just looked at the calendar and reminded myself that I’ve been living this country for twenty-three years, eleven months, and fourteen days. I’ve been in this country for that long. I don’t want to use the word “stuck.” But I’ve been stuck in this country for twenty-three years, eleven months, and fourteen days. I haven’t been able to leave because if I leave they won’t allow me to come back. And my mom, who has been in the Philippines since she sent me here, she and I haven’t seen each other for almost twenty-four years next month.

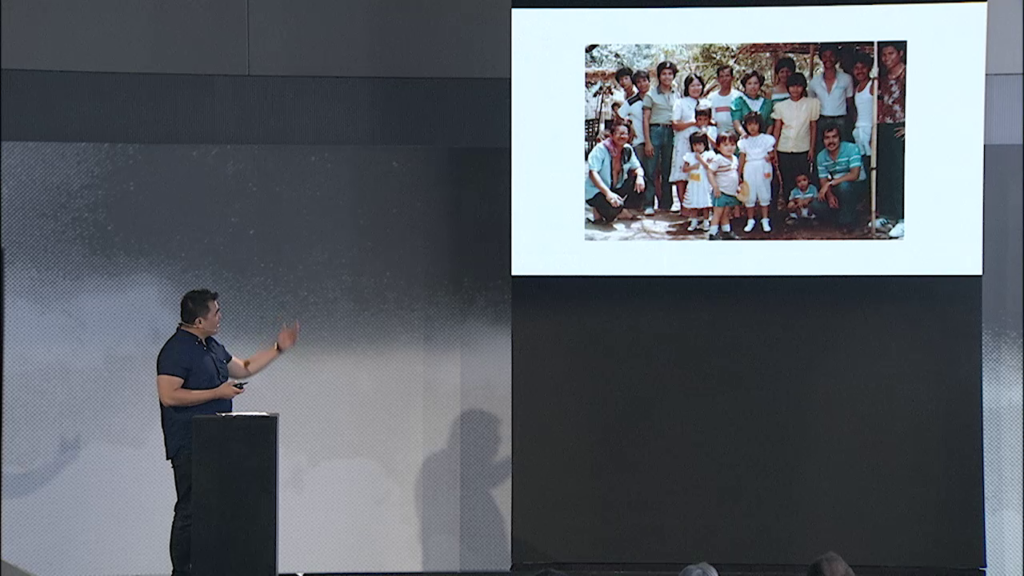

So just to give you a little bit of background, this is where I come from. That’s me in the Philippines, in the provinces where I grew up where there was no indoor plumbing. My grandparents in this picture immigrated to the United States legally in the early 1980s because of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act. I don’t know if you know what that is. That to me is the biggest legacy of the Kennedy family. If it wasn’t for that Act the country wouldn’t look as Asian and as Latino as it does now. That’s why the country looks the way that it does.

So this is my grandparents in the provinces of the Philippines. They got here and they tried to figure out how to basically get their grandson, their only grandson, to America. And because immigration law is really complicated, it’s not close enough of a relationship.

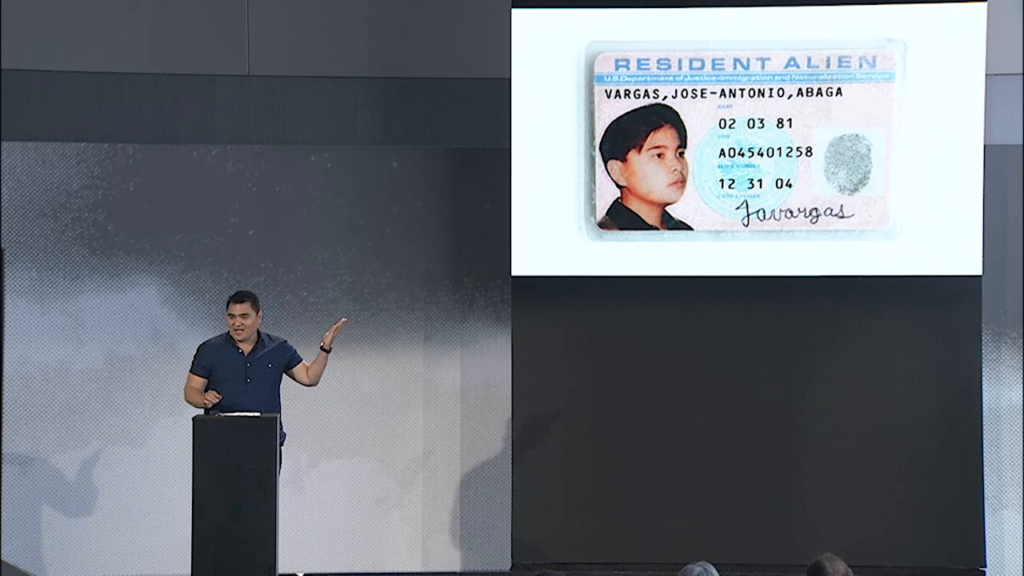

So they couldn’t get me here legally. So what they did is something that they should not have done. But they did. They found me this fake green card, to come to America when I was 12. Landed in Mountain View, California before Google got there. Before LinkedIn got there. 1993 is when I got there. I thought that this paper was fine. This is what I showed people. It says “resident alien” in it.

I didn’t know that it was fake until I got to the DMV to try to get a driver’s license. And the woman at the DMV said, “This is fake.” And the first instinct, the first thing I said to the woman was, “I’m not Mexican.” Because growing up in California, all you ever heard about was whenever somebody said illegal this, illegal that: Mexicans. And maybe I thought she thought I was a Mexican because my name was Jose Antonio Vargas, I was going to explain to her Spanish colonialism, all of that. And she said, “No no no. This green card is fake. Don’t come back here again.”

Confronted my grandfather and he said, “Yes, it’s fake.” I guess his plan was to get me here illegally then marry a woman, like Sandra Bullock in The Proposal, and poof! I have citizenship. The complication was around the same time I found out this was fake was around the time I found that I was also gay. Because of AOL chat rooms. Do you know what those are? AOL chat rooms?

So that’s how I found out I was gay. And I wasn’t going to lie about two things at once. And so I defied my own family. And you know how I did it? This thing called journalism. Mrs. Dewar, my English teacher, said I asked too many annoying questions and I should do a thing called journalism. Didn’t know what that was. But what I did know was when you’re a journalist you get this thing called a byline. So it says “by Jose Antonio Vargas.”

So I figured if I can’t be here because I don’t have the right papers…my name is on the paper. Doesn’t that mean I exist? And I figured hey, as long as I keep doing this; get a job at The Washington Post or The New York Times; write for The New Yorker, because people think that’s a cool thing to do; win some sort of a prize, like a Pulitzer or Pyulitzer—I never knew how to pronounce it, whatever; and be a political reporter, because people think that’s a good thing to do. Right?

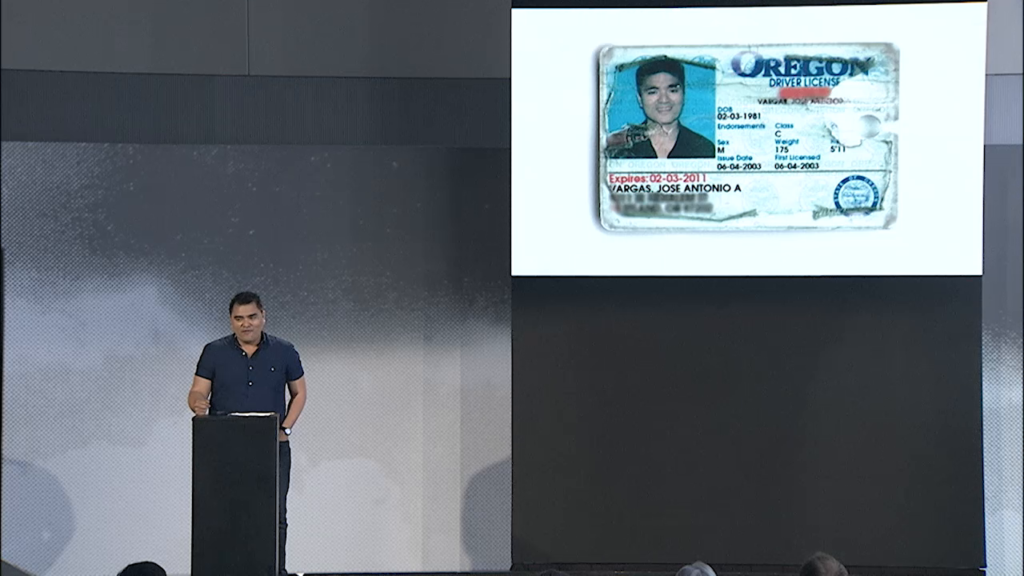

So I did all of that. The only reason I was able to do that—this is like everybody’s nightmare, your driver’s license blown up—was because of this. The Washington Post offered me an internship. One of my top papers on my list. And they said, “But you have to have a driver’s license to come.” I hadn’t drove after the DMV incident. So I researched, like any good reporter, at the Mountain View Public Library and found out that there were two states at the time giving licenses with no requirements for social security numbers. And one of them was the great state of Oregon. So I convinced a friend to drive me to Oregon, teach me how to parallel park, and poof I got the license. Well…you shouldn’t be clapping about that, but.

So this was issued June 4th 2003, ten days before my summer internship at The Washington Post started. As you can see it expired on February 3rd, 2011, which happened to be the exact date of my thirtieth birthday. I figured I had eight years to do everything I can to be “successful.” Maybe by then they’ll pass a DREAM Act or immigration reform or something would happen but you know, just keep writing, keep doing, keep doing all of this.

But everything on my list, The Washington Post, the Pulitzer, even writing for The New Yorker—the last story I did before I outed myself as undocumented was a profile of Mark Zuckerberg in The New Yorker. So I had done all of those things and nothing had happened. And they were really only two choices. Like any good reporter, I spoke to twenty-seven immigration lawyers, all of whom said— I told them, “Hey, my deadline’s coming up. What do I do?”

“Well, I would suggest you leave. Because you’re a writer. You can just write a book, sell a lot of books, go back to the Philippines, see your mom.”

And the more I thought about that the more I’m thinking wait a second. Like, I firmly believe that when you find purpose you find gratitude. And I’m very very grateful for this country. And everything that it’s allowed me to do, regardless of the circumstances. Then I did something that twenty-seven lawyers told me not to do.

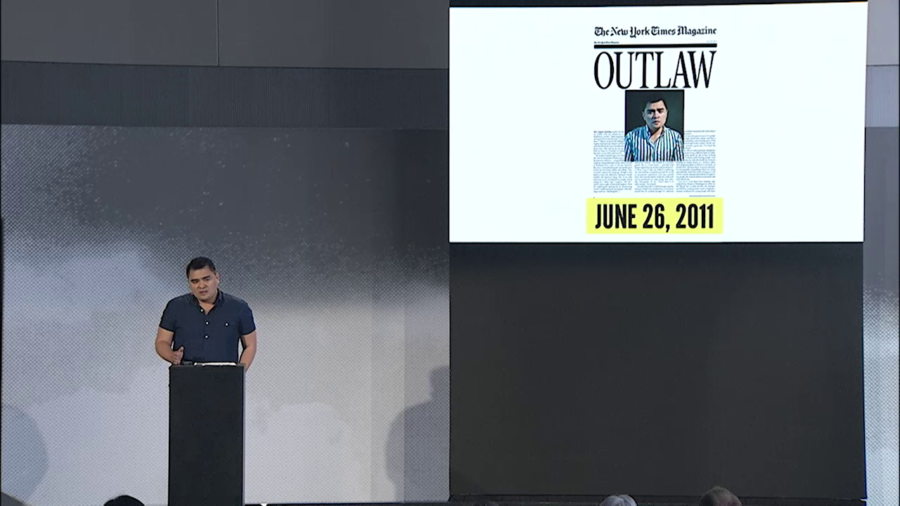

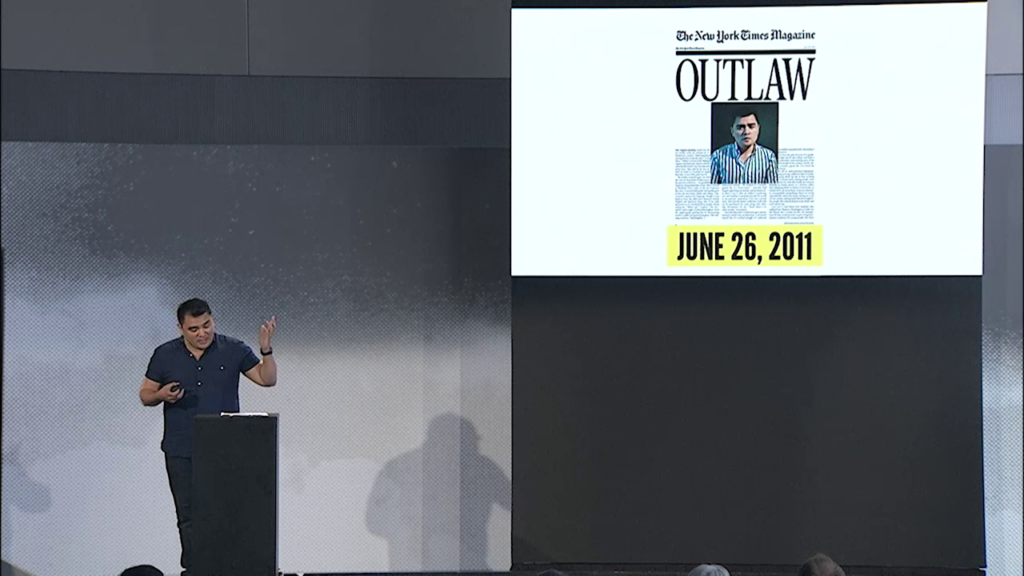

Isn’t that the most horrible photo you’ve ever seen? So in The New York Times, a 4,000 word essay admitting to everything I did just to work, survive, pay taxes, and social security. My lawyer said, “The moment you publish in The New York Times that you broke the law and you’ve committed fraud, we can’t save you.” No extraordinary ability visa like Milo can get you. No investor’s visa can help you. Not even marrying a guy—because now same-sex marriage is legal, that can’t save you. The moment you do this, it’s over.

But I firmly believe that when you find gratitude, you find purpose, and that’s why I did this. But the goal of this is mine is just one story, right. There are eleven million of us in this country who are here illegally. And how we define American in an era that is under siege, in an era in which there are forty-three million immigrants in this country— I don’t know if you know that. There are forty-three million immigrants in this country—the highest percentage we’ve had since the Ellis Island era. Out of the forty-three million, eleven million are here illegally without papers, like me.

So I’m Filipino. We’re like the Italians of Asia. We have big-ass families. So out of thirty-six family members I’m the only one who’s here illegally. I’m the only one out of thirty-six. It’s called a mixed-status family. There’s millions of families like us all across this country.

So how do we humanize this issue? A big part of it is we have a campaign called Words Matter. I am very sad to report that we’re still living in a time when The New York Times and The Washington Post and NPR and established news organizations that I used to write for myself still refer to people as illegal. Even though that’s actually factually incorrect.

I don’t know how this happened that we have allowed the language of Donald Trump. It’s not an accident that Donald Trump picked immigration as the central campaign issue. But for The New York Times and The Washington Post and NPR to still use that language to me is journalistically irresponsible. I’m proud that the Words Matter campaign actually encouraged the Associated Press to drop the use of the word illegal in referring to immigrants in this country.

We have a really important campaign, which to me is very important as a journalist, the Facts Matter campaign. If you go to our web site defineamerican.com, I really encourage you to download and print this. It’s a great uncomfortable conversation document. This lists six facts that you should know before you open your mouth and say anything about immigration. I’m proud to say that I gave it personally to Tucker Carlson live on television. I don’t think he read it.

But this is what the facts of this issue are. From the fact that to be in this country illegally is actually a civil offense and not a criminal one. Let me repeat: to be in this country legally is a civil offense and not a criminal one. So calling people illegal is factually incorrect.

I don’t know about you, I don’t know if you know, that undocumented workers like us have paid billions of dollars in taxes and social security. I recently was meeting with the top editor at The New York Times and handed him this document. And I said, “Hey, did you know that we’ve actually contributed $100 billion into the Social Security fund in the past decade?” I myself, personally have paid about $130,000, because I get that letter from the Social Security people. And I called them and I wondered, “Wait a second, so as a ‘illegal alien worker,’ which is what y’all call me, do I get any of this back?” No. We don’t. How many times have you heard that figure, by the way? That undocumented workers have paid $100 billion into the fund.

Now, there is absolutely no study that says that undocumented immigrants are more prone to commit crimes. We spend a lot of our time avoiding cops. So why we’d be more prone to actually commit more crime is a mystery to me. Yet, we have spread the lie so much on undocumented immigrants that there’s actually an office within the Administration called VOICE, the Victims of Immigration [Crime Engagement], meaning that if an undocumented person commits a crime, you as a neighbor can get to call VOICE and report them.

How have we spread these lies? And for me, the number one question I get asked— Bill Maher just asked me a couple of months ago before I went on his show, “Jose, why can’t you just get legal?” I’m a masochist. This is so much more fun. People actually—journalists themselves, thinking people. I don’t care, Republican, conservative. I don’t care what your politic— They have no idea that there is no process for people like us to “legalize ourselves.” Such process does not exist. And it’s not a one-size-fits-all process.

So these are the facts that we should know about immigration before we talk about it. Unfortunately, what I’ve learned in the past six years of traveling this country like a crazy person is that Clay Shirky—the great Clay Shirky—tweeted at me a few months ago and said, “Jose, you don’t bring facts to a culture war, man.” Let me repeat: you don’t bring facts to a culture war. I can’t tell you how many conversations I’ve had in Wisconsin, Ohio, Nebraska, Alabama, of people—mostly white working—class people—who feel that what was theirs is not their anymore. And why are they speaking Spanish at Walmart? Why are they taking the jobs? Why are they even here? Why are they even here?

The reality is we have been so busy calling people names, obsessing over borders and walls, and spreading misinformation that we haven’t even asked hard questions like why do people move? What does US foreign policy and US trade agreements have to do with migration patterns? Remember when those children started walking from Central America to here, and CBS News and a lot of organizations called them “illegal immigrant” children instead of calling them the refugees that they are? What did we do to Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala so that their countries got so violent that they have to come here? Who started the drug war? What did NAFTA do not only to the United States but to Mexicans, right?

And look, I understand that this is a very sensitive topic. Two years ago I did an event at Wilmington, North Carolina—it was actually a Tea Party event. And this man, after I said that there are four million Filipinos in the United States— There are four million Filipinos in the US. The third largest immigrant group. Two million Filipinos in the state of California alone. He goes, “Well, why are you guys here?”

And all I could say politely is, “Sir, we are here because you were there. That’s why we’re here.” Remember the Spanish-American war? Remember when you took the Philippines and it became a protectorate like Puerto Rico? Now, don’t get me wrong. We’re here because of the American Dream, right? We’re here because it’s a better life. We want something better for our children. The same reason the Irish and the Italians and the Germans did.

But why is it that when white people move you call it manifest destiny? You call it white man’s burden. It’s courageous. It’s necessary. When people of color move, what’s the question? Is it legal? Is it a crime? I found it really really interesting that my iPhone has more migrant rights than I do as a human being. This could be manufactured in China, delivered to Cupertino, and then to New York where I bought it. This thing can travel to more places than me and my mother can. And as technological innovators keep building things to open up, right, and connect the world, can we actually start thinking about about human beings and the fact that there’s nothing more natural than the human right to move? That to me is the big-ass question.

And we’re so busy obsessing over walls and borders without even facts to do with it. What if I told you that the fastest-growing undocumented population in this country are actually Asian immigrants? One out of seven Asian persons in this country is here illegally. One out of seven. But we’re so busy talking about Mexico and the wall. We don’t even know that. There’s about sixteen thousand undocumented Irish people, one of whom actually just got deported from this town, Boston, John Cunningham. I gotta tell you, just all the undocumented white people that I’ve met at airports and cafés, if I just counted them, it’s way more than eleven million people. But they just fly under the radar. We don’t even talk about undocumented black people. Although they actually get more detained and deported, in numbers and percentage, than undocumented Latinos or Asian people do.

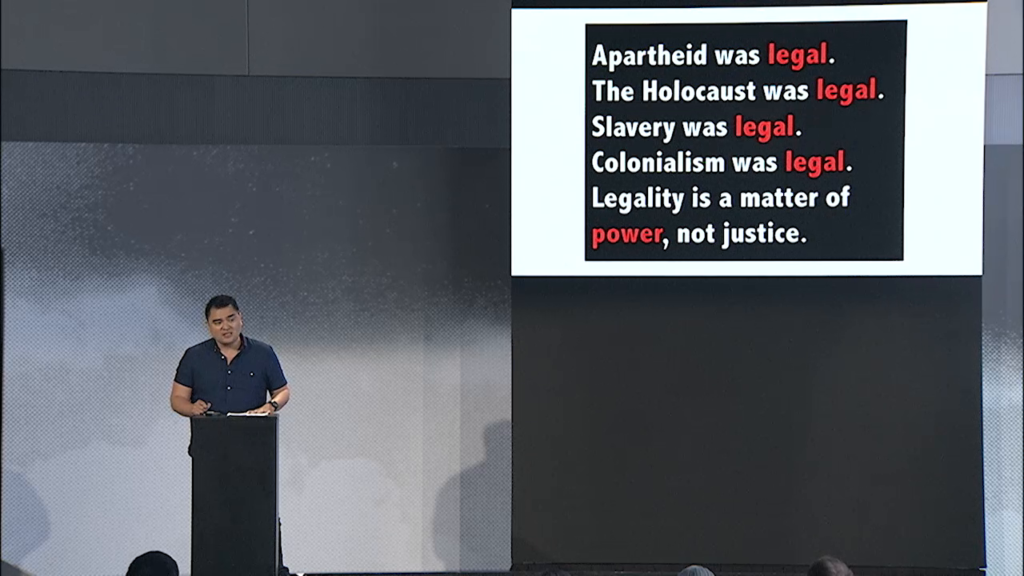

So these are the facts, right. And for me, since we are talking about legality, I think it’s really important to remember that legality’s a construct of power. Lynching, segregation, violently taking indigenous land, many more atrocities, all of these were legal, right.

Did you know that in 1790, that was the first time we as a country had a naturalization act? And the only people who could become citizens of America were free white people of good moral character. Did you know that it wasn’t until 1924 that we that we actually gave Native Americans citizenship rights? Let me repeat: we did not give Native Americans citizenship rights until 1924.

The reality is migration was never about legality. It was always about power. And here’s what’s really interesting. There are 244 million migrants in the world. Two hundred and forty-four million migrants in the world—that’s the most ever in the history of this world, according to the United Nations. And here’s what’s interesting about it. The majority of us are moving into countries that previously colonized or imperialized us. You might call that a global migration crisis? I call it a natural progression of history.

Now, why am I here? Why haven’t I self-deported? I’m here because of Mrs. Denny. She was my high school choir teacher at Mountain View high school. She was the first adult I ever told that I was here illegally because she wanted the choir to go to Japan for a Spring tour. And said, “Mrs. Denny, I can’t go. I don’t have the right passport.”

“Oh no no no, Jose. We’ll get you the right passport.”

“No, Mrs. Denny. I don’t have the right passport.”

Then she got it. She didn’t tell anybody—not the Principal, not even her husband. And the next day she told the whole class we were going to go to Hawaii instead. This woman…

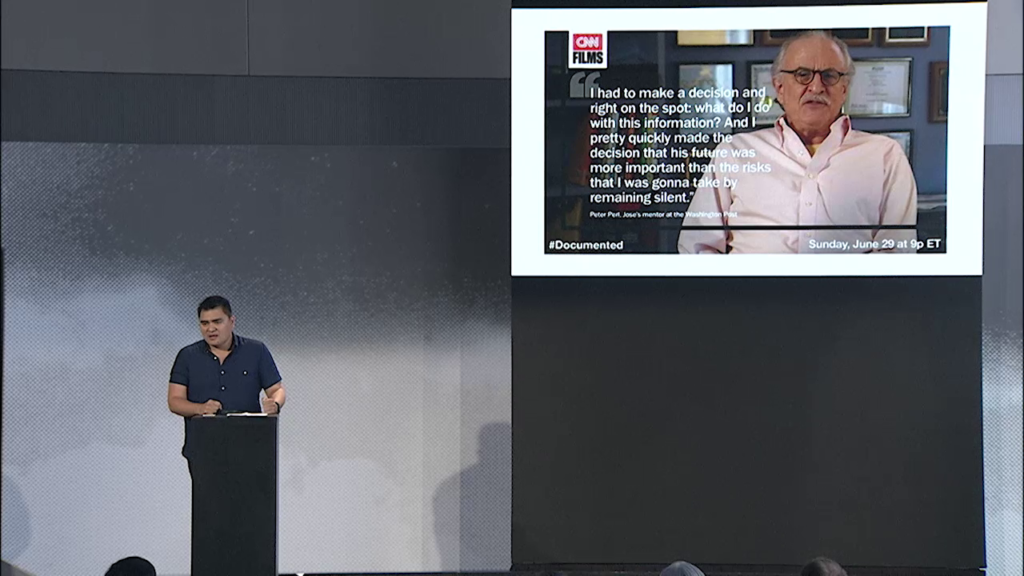

Still from Documented, CNN Films

Peter Perl, he was my editor at The Washington Post. He was actually the first coworker that I told. Because you know, it was one thing to be undocumented at the San Francisco Chronicle, it was a whole other thing to be undocumented in The Washington Post two blocks from the White House. I thought I had the word illegal tattooed on my forehead so hey. I thought Peter Perl, he always bought me Starbucks, I figured I could trust him.

Took him for a walk and I said everything. The fake driver’s license, the fake Social Security number, everything. And then he said two things. One, “You make so much more sense now.” Because apparently I was always walking around like I was on deadline or something. The second thing he said, which surprised me to this day, he said, “Jose, don’t tell anybody else. Just keep going.”

So when I was on Hillary Clinton’s campaign plane in 2008, following her around in Ohio… When I had to cover Sarah Palin in Indiana… When I ended up winning a part of this Pulitzer and I’m wondering wait a second. Aren’t they going to know that the Social Security number is fake? When I was asked to cover a White House state dinner for the Japanese Prime Minister, how am I going to get through the White House? Isn’t there like security protocol? But maybe because I look like this and I talk like this and it had “The Washington Post” next to it, nobody said anything.

I can only imagine how many Peter Perls are there all across this country, all across Boston, telling people like me, engineers, electricians whatever, to keep going.

And this woman is the biggest woman to me. Marcia Davis, she was my editor at The Washington Post for the longest time. She was the one who told me that before other people defined what success was for me, I had to define it for myself.

Now, some people may say that a green card or a passport is success. Don’t get me wrong, I want them. I actually want to go see Mexico—everybody thinks I’m Mexican. But as far as I’m concerned, what I’m doing is successful. This is part of my success. But the reality is Mrs. Denny, Peter Perl, and Marcia Davis are all across this country. And I don’t really have words to explain to you the fear, the palpable fear, that undocumented immigrants all across this country are facing in this new era. The reality now, though, is when you have privilege…like I did, right? Like I do. What are you doing to risk it? What are you doing to risk you privilege?

And we created this video at Define American all about allyship. What does it mean to stand up for your undocumented neighbors, classmates, and coworkers?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AiwFTD0cytA

So lastly, after Trump was elected President, my building manager in Los Angeles where I was living, in the apartment I was living, said, “Hey, it might be a good idea for you to move. Because if ICE showed up we can’t really protect you.” My lawyers then said it might not be a good idea to have a permanent address in case they issue a warrant of arrests. Because I got arrested in Texas three years ago. I got detained for eight hours and I got released. But the warrant could be issued at anytime.

So I actually moved out of my apartment and put everything in storage. So I’m living with friends who have a spare bedroom. Which is awesome. But, getting detained and deported? I can handle that. I have lawyers. I have a system in place. There’s four million Filipinos in this country, including Manny Pacquiao, who’s in the Philippines but who comes here a lot. So I think I’ll be okay.

But what I cannot do is stay silent. What I cannot do is stay in one place. What I cannot do is allow a presidency to scare me for my own country. So I am proud to say that I’ve been living in this country as of today twenty-three years, eleven months, and sixteen days. I’m an American, I’m just waiting for my own country to recognize it. Thank you.

Jose Antonio Vargas: Okay, questions! We have five minutes.

Nobody has a question? Is there anyone here who wants me deported? Let’s have a conversation about it.

Audience 1: Okay, what about DACA?

Vargas: Okay, how many people here know what DACA is, can you raise your hand? Oh…awesome that you know. DACA is called the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. It was an executive order that President Obama signed in 2012. Right now there’s 880,000 young people in this country who are here illegally but grew up here, who have to pay about $500 to the government so that the government doesn’t deport them for two years. And the government gives them a work permit, a driver’s license, and to not worry about anybody knocking on the door.

Can you imagine if you had to pay the government $500 to not deport you? So 880,000 young people applied for this, and Trump has said that he would get rid of it. He still has not. We don’t know what’s going to happen to it. But it’s going to expire. Judges, especially the great state of Texas— By the way, Texas has 1.8 million undocumented people in it. Is there a subway system in Texas that we don’t know about? How do you think 1.8 million undocumented Texans get around? They drive without a license. And then what happens? They get pulled over. Then what happens? They get detained. Then what happens? They get deported.

I have to tell you, though, Nico. When we asked that question of DACA here, the fact that you hear about immigration every day in the news, and yet we know so little about facts and process of this issue, to me is a journalistic irresponsibility of monstrous proportions. I don’t really have even the language for that because as a journalist myself I’m offended. But this is why we need more information out there. We need to figure out how to actually strategically get that information.

Right now Define American is training a few undocumented people to get on conservative talk radio. Train them to go on Fox News, conservative talk radio, so we don’t cede that ground. So please, pay attention to DACA. Call the senators that you want to call. We don’t advocate for anything political, but that’s your decision.

Audience 2: What was your motivation for going to so many Tea Party rallies?

Vargas: You know, I think it’s the journalist in me. I think Sarah Palin inspired me when I covered her in 2008. You know, you can’t hate something you don’t know. We did a show for MTV three years ago called White People. You might have heard of it. It was actually our way to kind of talk about race and immigration. And what was stunning to me after we did the film, MTV commissioned a study that said— I don’t know if you know this. Three fourths—the typical white American lives in a town that is predominantly white. And the average white American’s group of friends is more than 90% white. So if you’re one of those typical white Americans, where do you get to know immigrants? The news media you consume, and the television shows and movies you watch.

So for me it was really important to engage people. I gotta tell you, for me those are the best conversations. And they’re as surprised when I bring my tax forms with me from H&R Block. I mean, I have paid so much taxes I should be a Republican. And they’re like, “Aren’t you pissed that you keep paying these taxes but we don’t give you anything?” Oh hey, you know, I’m happy to be in this country. I’m happy. I want to pay taxes so we can have schools and libraries. I wouldn’t know where I would be without the Mountain View Public Library. But while we do that, can you at least not talk about us like we’re insects off your backs?

One last question and then I think I gotta go.

Audience 3: So, what is your definition of success for Define American and for the rest of your time, which we hope will be very very long here in America. But what would be your successful…

Vargas: You know, what has given me a lot of peace, by the way, is realizing that this is not just a national issue but it’s a global issue. Even though I haven’t been able to see the world. And I’m 36 years old, so I kinda do want to go see the world. Thinking about the fact that what we’re a part of is a global movement to me is very…I get a lot of peace out of that. I get a lot a peace that certainly after the election I have more news organizations contacting us saying, “Help us do this.” For example, we’re about have a pretty big partnership to do something on undocumented black women, which is something you never hear about.

So what gives me feelings of success are those kinds of things. But I have to say though, for me, the fact that I get to do this, the fact that people are getting detained and deported everyday and look, here I am doing this work. I employ fifteen people— What’s your name?

Audience 3: Tobi. [sp?]

Vargas: So Tobi, you can’t knowingly hire an undocumented person—although we know that people do. But, I can hire you. So undocumented people can own businesses and employ people. I’m a job creator, yo. So I employ like fifteen people. And apparently I provide really good health insurance and benefits. The same benefits that I can’t get myself because I’m here without papers. So I have to buy my own private health insurance.

But it gives me a lot of peace knowing that what we’re doing is succeeding. We just have to really scale it. Thank you so much for this time.