Bahador Bahrami: In the course of Donald Trump’s rise to power, people have repeatedly been asking, “Why did he tweet that? What was he thinking about?” Our fascination with his mental states highlights a very important question for us: What happens in our minds and brains when we try to influence others?

This is a very common problem. Imagine Granny Smith and her two grandchildren Max and Moritz. Granny is looking for a new phone, and Max and Moritz know that whoever makes a better impression will have a better chance in the granny’s will.

But, just like in life, Max and Moritz are not equal. Max is the favorite, and Moritz is the underdog. So our question, we can rephrase it in terms of, given their differences, how would they go about persuading the granny?

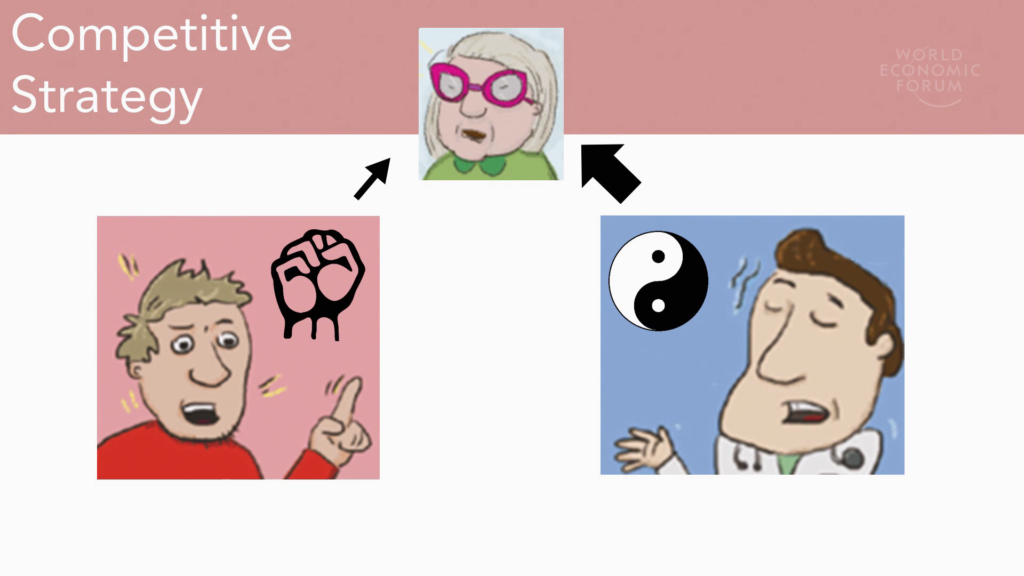

So one possible strategy for Moritz is to be competitive. That means we might be radical and offer very strong opinions when we think we are the underdog. We have nothing to lose, and we might as well risk everything. In such a situation, what Max has to do on the other hand is to maintain the status quo.

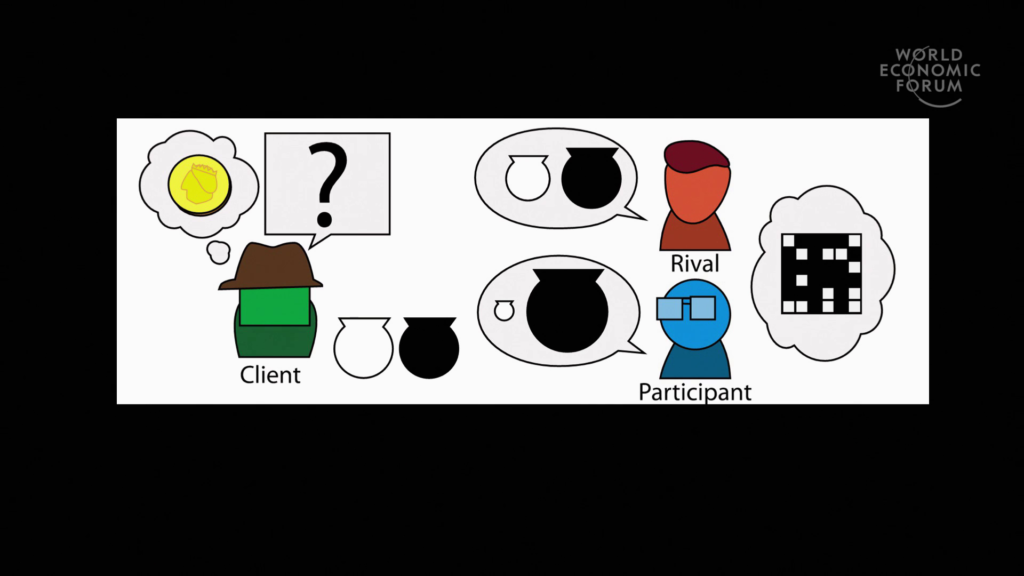

The alternative strategy is to be defensive. We ran a study in our lab to compare these. Groups of three people came to our lab and were studied in the course of a client/advisor game. The client is looking for buying a lottery ticket but doesn’t know which one to buy. And the advisors have private information and can advise the client.

But they go into three separate rooms. And they believe that each one has been given the role of the advisor and the others, one of them is the client and the other one is the rival. But all three of them are actually advisors playing against a computer.

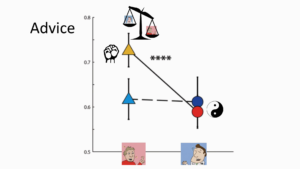

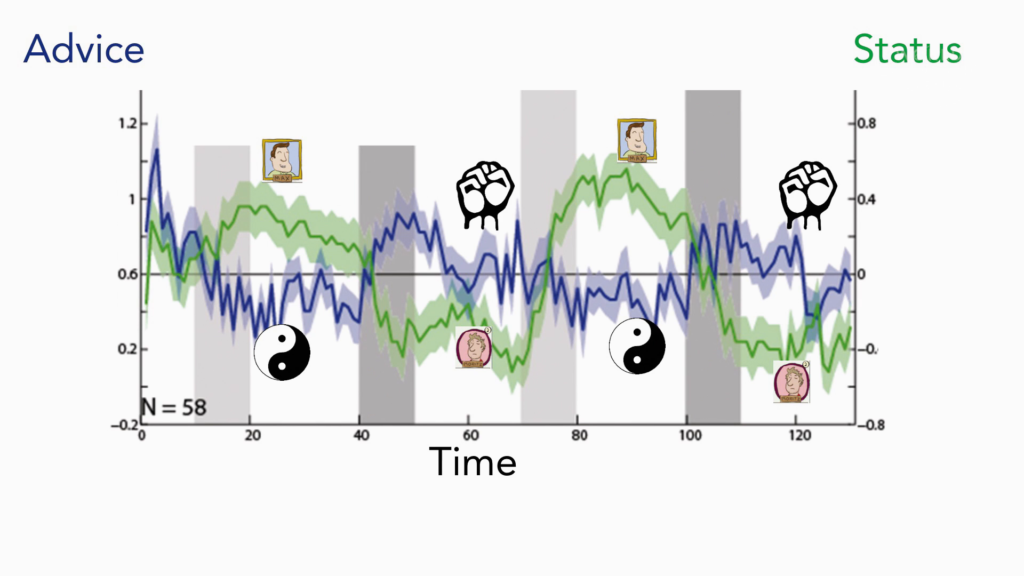

The results showed that people indeed do follow the competitive strategy. Every time they are in the position of Max they offer a conservative opinion, which is the blue line. And every time they are in Moritz’ position they offer strong advice. They go radical.

But we also found that another important factor plays a very important role, and that is social comparison with your rival. What we found in the results is that people really care about how well they are doing compared to their rival and not just how much influence they have over their client. What the next slide will show is that people are distinctively vocal when they think they have done better than their rival but they have been unfairly ignored by the client. And that’s that triangle up there.

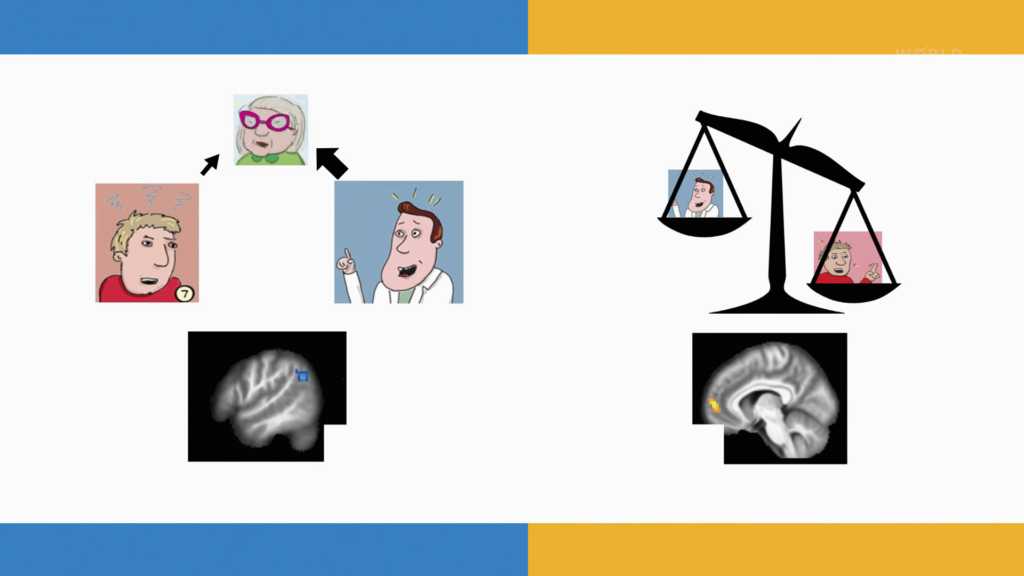

So, in order to see what happens in the brain, we conducted the same experiment in an fMRI scanner in order to see if we could trace the signatures of similar psychological processes in the brain response.

What we found was that the human parietal cortex on the right hemisphere, which many people believe tracks other peoples’ point of view, actively tracked people’s position in relation to their client, and their influence was correlated strongly with the brain signal that we got from this brain area.

Another part of the brain, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, was also found in this study. This brain area is an area that a lot of people believe is involved in value-based decisionmaking. And we found that this area is the area that follows and tracks the moment-to-moment comparisons with the rival.

So, putting these together, what our studies show is that people combine the information about their influence over their clients, and comparison with their rivals, in how they come about trying to influence others to make different decisions. We found both of these both in behavior and in the brain response.

Well, at this point we can come back to our original question and say, “Are we any wiser about what Trump thinks about?” Given our data and our findings, we believe that Trump follows a strictly competitive strategy. It seems like he constantly believes he’s better than his rivals. But at the same time, it seems like he constantly feels that he’s ignored by his clients, the American public. Thank you.