Dan Hon: Good morning. Everyone hear me okay? Alright. Okay. So I’m Dan. And I’m gonna start off a little slowly for everyone this morning, because this talk is mainly a slightly extended joke about Star Trek. So you don’t have to think too hard yet. And hopefully enough people in the audience know enough about Star Trek to be able to get the joke. Fingers crossed.

So, first I’ll do a little bit of talk about the Star Trek interaction design joke. I’ll share some ideas about why it’s easy for design to borrow from science fiction. I’ll talk about a land of missed expectations and unforeseen circumstances and consequences. And then we’ll talk about some ideas about how we can responsibly borrow from science fiction. And I’ll share a couple of examples that I find interesting. And fingers crossed I can get all of that done inside of fifteen minutes.

So. First, like I said this is mainly a joke about tea. This is Captain Jean-Luc Picard. He’s the captain of a starship in the 24th century. And it has a very very sophisticated computer that you can talk to. And from what we can tell over about seven years’ worth of TV shows and a bunch of movies, is that he mainly uses his computer to do this. If we have sound… That’s the joke. That he is ordering tea from his computer, and he’s saying, “Tea. Earl Grey. Hot.” Thank you Captain Picard.

So, Star Trek’s vision of a voice interface to computing was and remains incredibly compelling. So much to the extent that about three years ago, Amazon included “Computer” as a wake word to the Echo so that we can pretend to talk to the first mass-market voice assistant as if we’re on a spaceship in the 24th century.

Now the thing about this is that you can’t think too hard about how it actually works. Because if you start thinking too hard about how Captain Picard orders his tea, then you start realizing that maybe it doesn’t work the way you think it should work. “Tea. Earl Grey. Hot,” is a three-word command phrase. So “tea” makes sense. He’s specifying the kind of drink that he wants

“Earl Grey” also makes sense, although you might want I don’t know, chamomile, or green tea. And perhaps don’t think too much about green tea because there might be different kinds.

And then it’s the last word that kind of throws me, if you’re the kind of person who pays too much attention to these things. Because why wouldn’t you want hot Earl Grey Tea? You might want cold tea, or tepid tea, or if you’re American you might want iced tea but probably not iced Earl Grey tea.

But anyway, none of that is the point. Talking to computers is awesome and we should get right on those Alexa and Siri skills. And so…wait. Maybe “Tea. Earl Grey. Hot” is actually the name of a 16 million line of code macro that Picard wrote in the academy to make sure that he got a passable hot drink. And it’s not actually being parsed as natural language, it’s something that he has put years and years and years and years of effort into to get a minimally-viable drink that he could possibly enjoy.

And I feel a little bit like this because when I have tried to use Alexa on my Echo in my kitchen, I invariably end up using a stilted phrase like, “Computer, tell skill replicator to prepare recipe ‘Dan’s Favorite Drink’ from Dann’s recipe collection.” And then it adds my favorite drink to the shopping list.

This is not the kind of future that we wanted. But, that was back then. This is a TV show from the 90s so maybe things have proceeded from them and we’re doing a little bit better.

We have iPhones and CBS has brought Captain Picard back. Here he is. He’s much older now. The new series aired earlier this month. And all we need to see is whether he orders some tea—which he does. Which is fantastic, we’re on tenterhooks. So what’s he gonna do? He’s going to order some tea. He says, “Tea.” “He says, “Earl Grey.” Right. With you there so far. And then he says, “Decaf.”

This doesn’t make any sense. I mean, the decaf part makes sense because he’s 90 years old now, and maybe he just wants to slow down a bit. But shouldn’t he be saying, “Tea. Earl Grey. Hot. Decaf.”? Or some other combination: tea, decaf, Earl Grey, and then hot. That would make more sense.

But he doesn’t say that, because those four words don’t scan. Because they don’t do the job in as an aesthetically pleasing way as just, “Tea. Earl Grey. Decaf.” Because what we’re supposed to be learning is something about Picard and something about the character. It’s not necessarily a model for interaction design. Star Trek is a story, not an interaction design manual.

Apart from when it is actually an interaction design manual. So. This book was incredibly influential to 13-year-old me.

So, why do we keep borrowing from science fiction? Well, there’s a book that I very highly recommend called Make It So. It’s by Nathan Shedroff and Christopher Noessel. It came out in 2012. And it also has a wonderful web site that goes along with it where Chris is going through, cataloging every single science fiction interface that he can find and critiquing it. And it’s what I consider a textbook on critiquing science fiction as a source of interaction design and I’m fairly sure that it’s much better than this presentation and has much better jokes in it.

What Shedroff and Noessel have to say is that Science fiction creates interface as byproduct. Its focus is entertainment, and this affects the interfaces that come from it.

So what does that mean? It means that everything that’s shown or described or exists to us in a story, in a film, in a book, in a comic book, exists in a very narrow context and domain. And some of those domains might sometimes align with the needs that we intend to address. Which is why science fiction serves as a useful provocation. But I’m gonna talk about three reasons why I think science fiction is so compelling for us to keep coming back to it. Why do we keep using it as a source? Why is it so interesting?

So the first is that we love stories set in believable worlds. We love stories that we can lose ourselves in. That are sufficiently rich enough. And that doesn’t mean that the worlds have to be realistic, just that they are consistent enough. So, those might be the post-apocalyptic world of 2006’s Children of Men, which admirably showed a post-Brexit Britain. It might be the harrowing Chernobyl-style documentary about a failed genetic engineering theme park in 1993’s Jurassic Park. Or it might be the surveillance state of 2016’s Jason Bourne. And these science fictional worlds immerse us and create a suspense of disbelief. In other words they work. They bring us in. So that’s part of why they’re compelling.

The second is that I think we love stories that are about capability, mastery, and agency. I think stories about people succeeding resonate with us. They are not the only stories that resonate with us but I think that’s an important point. And if I were to handwave an unsubstantiated cognitive psychology explanation, I would probably say something like our mirror neurons are being triggered by seeing someone do something that we want to do, and we’re copying them. Or, a more facetious way of talking about this would be that we like to cosplay being competent about something. We like to pretend that we can actually get something done.

So, it’s 2020 and you can’t make a pop culture reference without including something to do with Marvel’s cinematic universe. So I’m contractually required to include this type of reference. This is Tony Stark, down there in the bottom right. And he has just figured out time travel, which no one else has managed to do. Which I think counts as a check in the “mastery” box.

I’m not saying that this interface looks cool, and more that this interface is tied up with telling the story that Tony Stark solved something really difficult. Part of its job is to show how capable Tony Stark is. That’s Tony, and I have another example.

And we definitely don’t have sound. This is Lexi, and this joke is much more funny if you can hear her say that, “This is a Unix system. I know how to use this.” And what we see in this is we see her using something called fsn, which is a real piece of software. It’s the file system navigator that came with SGI’s Irix OS. And fsn and was a real thing and it was intended to show off the 3D rendering capabilities of their workstations.

So, what we’ve got here—the point here is that we understand that Lexi is an amazing, smart girl. She’s got agency. She can figure out problems. She succeeds at them, and manages to lock a door. And also you should buy SGI workstations.

Here’s the last one coming up. I think another thing that science fiction does, especially in film, is that it helps us understand characters. It can be used to create understanding with and about another person, separate from what those people do. So it’s science fiction that enables us to understand a little bit of what it’s like to be another person.

So what we’re looking at here, you’ve seen this before, people use it in loads of examples. This is a representation of the internal state of the Terminator from the 1984 movie. But this obviously isn’t what the Terminator experiences at all. At best it’s something like a debug mode for humans to understand what the Terminator is doing. But we never see how anyone might be able to access it. It includes things like English language explanations of what’s going on. It is not for the Terminator, it’s for us. It’s for us to help understand; it’s serving a plot point.

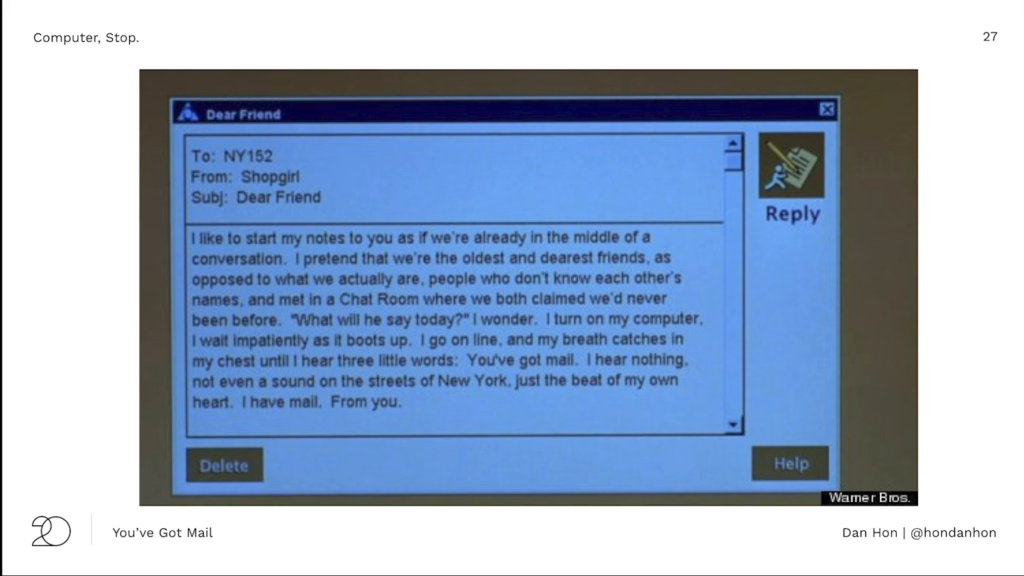

And the mirror side of that is that— This is from 1998. Now we have the equivalent of seeing a character’s diary or correspondence but on the screen.

And I do have one last example in this bucket. Which is, I was going to try not to include a reference to Minority Report because apparently everyone who does a talk about science fiction interaction design must include a talk about Minority Report. What I’m gonna say is that maybe the reason why we keep going back to the world of science fiction is because your client has been watching a $100 million pitch video from someone else, that someone else paid for, and now they want to buy it, even if it makes no sense but because it made sense in the movie.

My point here is that science fiction is popular culture. Which means it’s a common point of reference. Which makes it something that really easy to understand for customers and clients. And also they think it looks cool.

So what can go wrong? What could possibly, possibly go wrong if we start borrowing from science fiction uncritically, because part of its job is to be compelling and to be something that’s emotionally relevant and resonant.

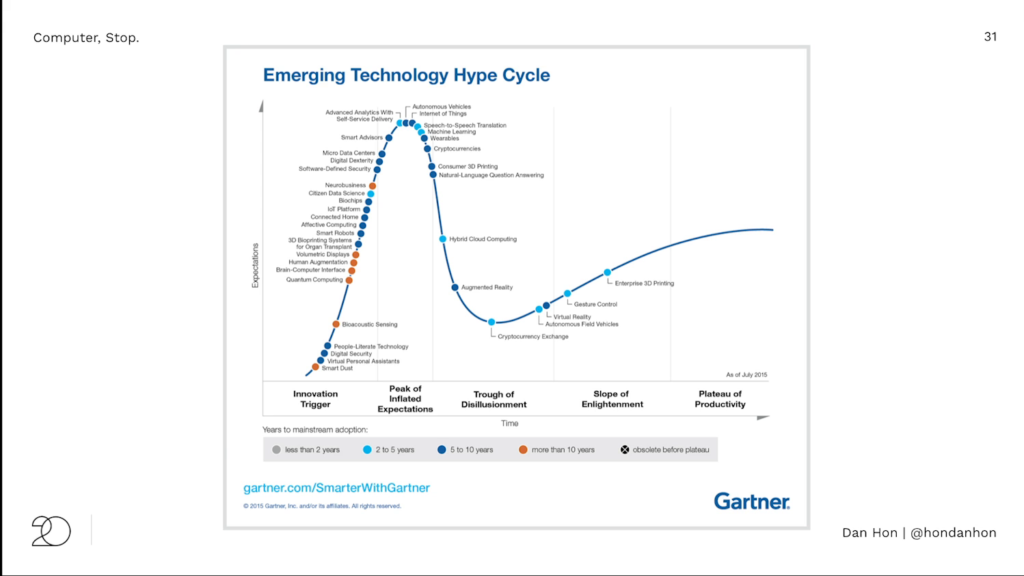

Well, we could lose trust. Who here is a fan, and I use that in the lightest possible sense—of the Gartner Hype Cycle? This is the hype cycle that you can kind of shorthand reference to how terrible blockchain is at any moment when people are talking about it. The most exciting part of the hype cycle for me is actually this bit, which is the trough of disillusionment, and not the peak of inflated expectations. It’s the bit where we all suddenly realize how terrible something might actually be.

And I think a good example of that is, because science fiction is part of pop culture, when it collides with reality the results can be incredibly disappointing. Customers and users and clients have seen the pitch video. They paid attention to it. It was emotionally resonant to them. And they might even have paid to watch the pitch video. Science fiction has made promises to people that our products frequently aren’t even able to keep. And there are promises from pop culture that exist alongside any promises from marketing.

So again, it’s my example of I see the movie, something comes into my home and I try to tell it that I’d like to have tea. And then the actual experience is super clunky. Because actually it’s really hard. It’s not as easy as what it looks like in the movie.

It might be something like imagining that Bowman might want to send a message to the Odyssey, and then HAL instead replies, “I couldn’t find the Odyssey in your address book. Did you mean Martin Odessa?” And sometimes the easy flow is subverted in pop culture, but not often.

Now I have one last video. So we’ll see if the sound works for this one. And if not we can totally skip it.

No. So, I will briefly explain it. This guy is a junior lieutenant. That’s super important to understand. He’s in another Star Trek series. And he has just tried to order tomato soup. And for some reason, the computer says to him, “Which tomato soup did you mean? There are forty-seven different kinds of tomato soup in the database.” And he has to drill down a menu three levels deep to get to the tomato soup that he wants. Why is it that he has to do this, but Captain Picard gets to use three words to describe his tea? It means, or it’s an example of, not being able to interrogate the happy path.

Which leads me onto this whole idea of, in Minority Report for example, we only start to see undesirable states, or states off of the happy path, when Tom Cruise’s character, an otherwise competent white middle-class everyman, gets stuck in the system and then we see what it might be like for anyone else who’s not like him.

Star Trek’s model for voice-computer interaction portrays a world of ubiquitous computing as sort of everywhere. That’s seductive but it’s fiction. It doesn’t provide really any framework to address issues of what persistent total surveillance might look like. We get to see the good version. We don’t get to see the horrible version that might be something like Ring teaming up with police precincts all across America.

And lastly, it shouldn’t really need to be said in 2020 but science fiction has its own issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. It’s historically and overwhelmingly white and male. And while progress has been made in the last few years, some of the most influential science fiction remains rooted in a very particular kind of social, and racial, and economic context. In other words, most of the examples that we see and resonate with us only work for certain people.

So. How can we be responsibly inspired? Or, in the words of famous scientist Jeff Goldblum, how can we decide whether we should do something just because we can?

More seriously, there’s a fantastic piece of writing that I saw last October from the Near Future Laboratory. And their point I think is a very simple and easy-to-understand one, which is science fiction is not design fiction. And what that means is that creating an artifact forces you to get into the details of your world in a way that writing a story just describing something in the story, and critically the story part, doesn’t. Because when writing it’s super easy to skip over uncomfortable details in favor of the big picture. And design fiction, actually creating usable artifacts, makes you sweat the details. Good design sweats the details through and through.

So. I have two kind of jokey ways of illustrating this. One is the case for mundanity. You might not actually be the hero. And fair warning this is going to be a series of super dumb jokes.

When we look at science fiction, can we imagine what the mundane uses might be? So, William Gibson says that the street finds its own uses for things. But what would it look like if the street was entirely populated by characters from The Office? Or in other words, you might not be the hero, you might be Karen in Procurement. And what if we never ever get better at PowerPoint.

I mean this is another scene from Star Trek, and it looks super interesting. Look at all that data and charts and people making very important decisions. It practically looks like an information knowledge worker vision video for the 24th century. But if I replace it with PowerPoint, we get a very different sense of what’s going on.

I mean look. Here they’re looking at the interstellar high-energy particle density. Very very important science going! But if again I replace it with a map from the Pentagon of the governments in the Middle East…doesn’t really work as well.

And this works for Star Wars as well. Look, here’s Darth Vader. He is reviewing the environmental impact assessment for the Death Star.

Here’s the briefing for the Death Star bombing run. Here’s the bit that you don’t see where they have to go over the logistics for the mission.

So there’s another case mundanity. How might these things work if they don’t work on the happy path? Another vision video here. So this one’s from Microsoft. And this is all about sharing screens. Wait for it. Blah blah blah blah. Exciting classroom. And then right here, we’ve got the super simple flip. And then we get to see something on someone else’s screen.

And that would be super amazing if that’s how sharing screens works. But I’m going to be mind-numbingly dumb and bloody-minded about this. So we’re back in Star Trek on the Enterprise and here’s a big screen on the bridge. You might have an away team that’s doing a bunch of user research, not using phasers and shooting people. And they’ve discovered a bunch of stuff. And your people back on the bridge are really interested and want to see what’s going on.

So I’m imagining, “Sir, the nebula is emitting readings we’ve never encountered before.

And the first officer says, “On screen.”

And what he does is he takes a screenshot of his terminal, using Print Screen or…is it Command-F4‑W? to grab a screenshot of the window, and then DMs is to the main screen. Because that’s how people actually do things. And this is a mundane, stupid example of how things might actually work in practice.

So I’m near on time, and I promised that I would show two short examples of inspiration from science fiction that I find intriguing and that can be interrogated.

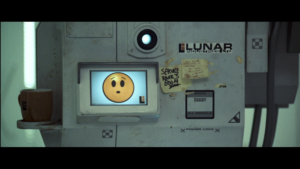

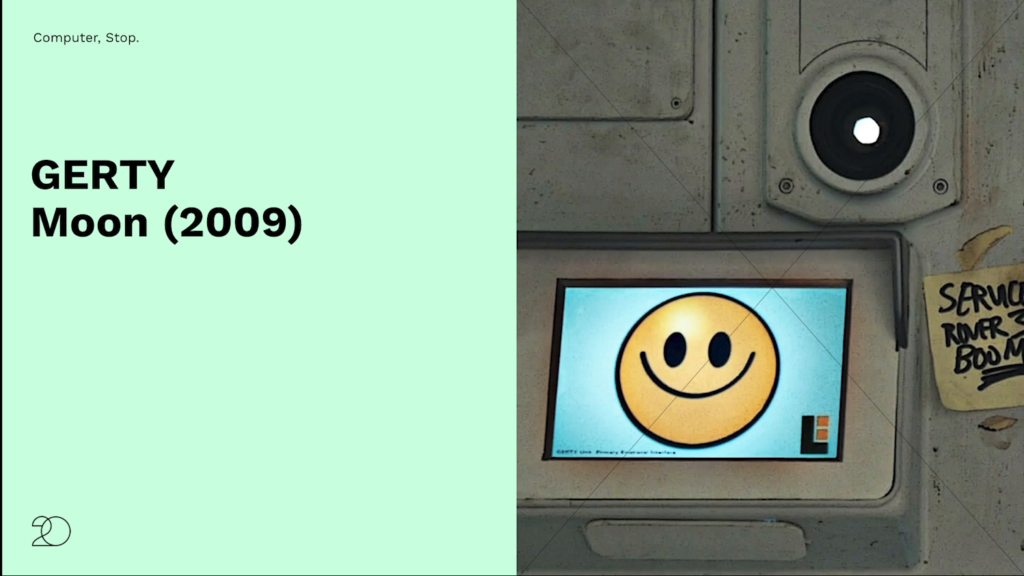

So, the first one that I have is GERTY. GERTY’s a robot from Duncan Jones’ movie Moon from 2009. And what I think is amazing about GERTY is how it—GERTY—uses emoji to represent its internal state.

Here’s GERTY happy. Here’s GERTY being hnnnn. A bit kinda hunnh. Very sad. Sorry I’m going to have to kill you because I’m an evil robot.

Here’s another example from Interstellar, from 2014. So there are two somewhat intelligent robots in there that you can have a natural language conversation with. And again, they have this kind of screen on the outside that lets you see on the inside.

And what I’ve seen from that, and what I really appreciate, is the Baxter robot that came out in 2011. Which again uses that screen to show internal state in a way that you might otherwise not see.

And my last example is again something from Star Trek, the communicator badge. So this is kind of the wearable that Picard wears for communication. And the the real-world example that I find really interesting is the Withings Activité watch. Which is a smart watch that does activity monitoring. It does stuff like heart rate monitoring. But it doesn’t have a screen. And that’s what I find super interesting about this is, what type of smart thing, or what type of health wearable can you get when it doesn’t have to follow that model or it’s inspired by something that has an entirely different type of interface.

So. Wrapping up. Inspiration from science fiction is rooted in storytelling. I think this is a really important point. It’s only there to tell you a story. It’s only there to tell you about the character. It’s only that to advance the plot.

So these storytelling artifacts have specific goals. And what we can do to be smarter about them is that we can interrogate them by creating actual artifacts and not telling stories. Or, as I prefer to do sometimes, by being bloody-mindedly stupid.

That is it. Thanks very much.