Dave White: My name is Dave White, and I’m a Professor in the School of Community Resources & Development at Arizona State University, and Director of the Decision Center for a Desert City.

I spent the summer of 1998 rafting the Colorado River through Grand Canyon National Park, working as a graduate student on a social science research project. I rafted more than 1,300 river miles, and spent about sixty nights sleeping under the most brilliant stars imaginable. And this extraordinary experience inspired a commitment to ensure the sustainability of perhaps the most significant natural resource in the West, Colorado River water.

Now, river rapids around the world are measured on a six-point scale, with Class I being easy—little riffles of water and no risk. Now, Class VI are violent, turbulent rapids—waterfalls really, with significant risk of injury or even death, where rescue may be impossible. Now the whitewater rapids on the Colorado River in Grand Canyon National Park are so wild that they are measured on a ten-point scale. When you reach river mile 179, you encounter the biggest and most fierce whitewater rapid in Grand Canyon, Lava Falls. It is a ten.

To run Lava Falls in a river raft, you have to navigate a series of terrifying obstacles. Stay to the right of the Ledge Hole!, a waterfall—really standing wave, thirty-seven feet tall that can suck in the boat, toss the rafters into the water, and trap your raft in a permanent spin cycle. Now, power forward hard and punch through the V wave! Watch out for the Cheese Grater, a huge boulder on river right. Just like that, thirty terrifying exhilarating seconds later, you’re through. What’s the reward for running Lava Falls in a river raft? You pull over at Tequila Beach. Celebrate. But be prepared to help out with the next group of rafters.

Now sometimes, of course, there is conflict on the river. Rafters disagree about the best path to take through the rapids. People argue about which challenge is the most dangerous, or deny there’s any danger at all. And sometimes, after camping with people for two weeks, you just don’t like each other very much. Now running Lava Falls takes courage. It takes skill, and experienced leadership. And, more than anything it takes teamwork. Your power to navigate the rapids comes from everyone in the raft, pulling together in the same direction at the same time, toward a common purpose.

The story of running Lava Falls is the story of the Colorado River in the American West today. Right now, we are in those relatively calm waters above the rapids, enjoying the beautiful canyon scenery. But, now we begin to hear the ominous roar. In the American West we face challenges managing the Colorado River. Instead of the Ledge Hole, the Cheese Grater, or arguments between rafters, we face population growth, drought, climate change, and conflicts between the states. The solutions to these problems will require courage, skilled and experienced leadership, and collaboration.

The Colorado River is the lifeblood of the American West. It provides water to one in ten Americans across the West in cities like Phoenix, Las Vegas, Denver, and Los Angeles. Hydro power plants along the river provide low-carbon renewable electricity. The water irrigates millions of acres of land to grow crops like alfalfa, cotton, and lettuce. The river supports national wildlife refuges, and national parks including Grand Canyon, stimulating over a billion dollars in annual tourism revenue. And the river is integral to the history, culture, economy, of dozens of Native American tribes.

Through a hundred years of collaboration, productive conflict, planning, and marvels of engineering, we developed a remarkably robust and resilient water system that supported economic development and population growth across the region. The system was managed mostly by technical experts. Lawyers, politicians, and engineers—a group we affectionately call the “Water Buffaloes.”

Now, my undergraduate degree was in American history, so I tend to think to understand our current and future challenges, we must look to the past. The Colorado River is managed through a patchwork of decisions, laws, and court regulations that are collectively known as the Law of the River. These agreements guide the allocation of the water between seven US states, and the nation of Mexico. The foundation of it all is the Colorado River Compact of 1922, which defined the relationship between the Upper Basin states of New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming, and Colorado—where most of the water originates, and the Lower Basin States of Arizona California, and Nevada, where most of the water demands were developing.

When the states couldn’t agree on how to divide the water, the federal government intervened. The river would be divided equally, with each basin getting the right to develop 7.5 million acre-feet of water annually. An acre-foot is a water management term. It’s the amount of water needed to flood one acre of land to the depth of one foot, or about the amount of water needed for two to four households in the Southwest for a year. Later, another 1.5 million acre-feet was promised to Mexico. That’s 16.5 million acre-feet in annual allocations. Remember that number, 16.5 million acre-feet in annual allocations. It will emerge further down the river like a boulder hidden in the rapids.

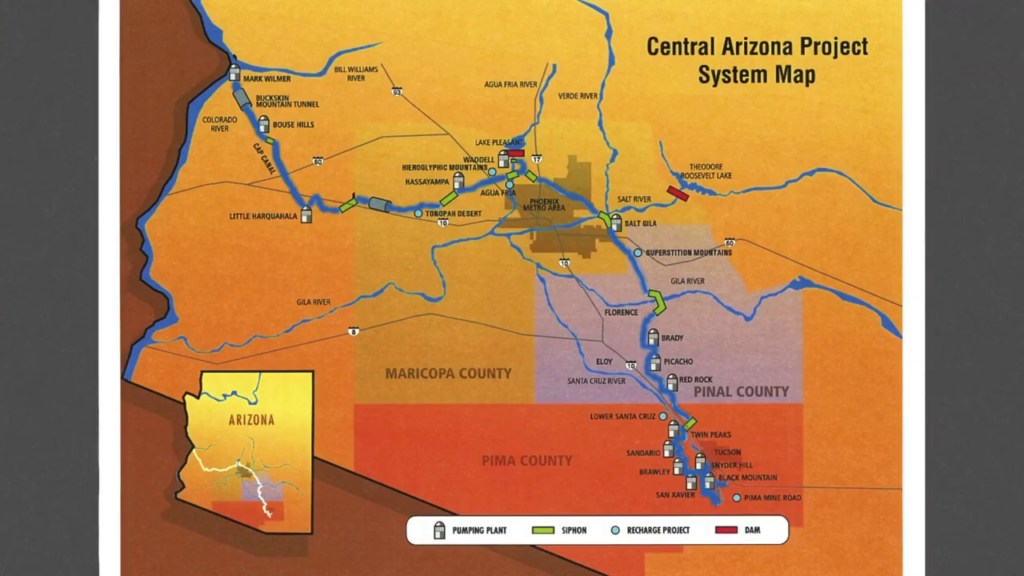

Over the next eighty years or so, we all navigated the river pretty well together. Yes there were lawsuits. In 1964 the Supreme Court settled a twenty-five year-old dispute between California and Arizona, ruling in Arizona’s favor. Following that decision, Arizona gained approval from Congress to build the Central Arizona Project canal, a $4 billion aqueduct to pump Colorado River water 300 miles across the desert, uphill, from Lake Havasu City to Phoenix and down to Tucson. The CAP canal was completed in 1985, and it significantly reduced Arizona’s reliance on groundwater.

However, as part of the political bargaining in Congress to get the CAP canal completed, Arizona agreed to give up all of its Colorado River water during times of severe shortage, even before California loses a single drop. The decision was critical to keep all of the rafters paddling in the same direction at the time.

By the turn of the 21st century some new problems were emerging, like flash floods altering the course of the river, creating new and more treacherous obstacles. Let’s start with the promises we’ve made compared to what the river can deliver. Remember that number? 16.5 million acre-feet in annual allocations. Well, it turns out when we divided up the river, we based our estimates on an extremely wet period, when the ten-year average was about eighteen million acre-feet. Well, the long-term average annual flow is more like 14.8 million acre-feet. So we’ve promised about 1.5 million acre-feet more than the river has delivered.

That wasn’t a problem for a long time since the states weren’t using all of the water that they were allocated. And the basin-wide storage capacity is about sixty million acre-feet, or four times the annual flow. But as states like Arizona developed and began to use their full allocation, the supply/demand balance began to get tighter and tighter and tighter, like canyon walls closing in on our rafts.

Then came the drought. Since 2000, we have seen the driest sixteen-year period in the last 100 years. And one of the driest periods in the last thirteen hundred years. The ten-year average is now down to 13.4 million acre-feet. Those reservoirs that have been so important, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, are down to about half of their capacity. Recently, we’ve seen the lowest level since the dams were completed. If those reservoirs continue to decline and Lake Mead reaches a critical threshold of 1,075 feet above sea level, the Secretary of Interior will declare an official shortage on the river. Under the rules set forth in a 2007 agreement between the states, Arizona loses about 10% of its Colorado River water. If the lake drops lower, the cuts get worse. Remember, according to the bargain Arizona loses all of its allocation before California loses anything. And if the lake levels drop too low, the dams can’t produce power.

On top of these issues comes climate change. According to the National Climate Assessment, our region will face rising temperatures, which increases demand. And decreasing precipitation, which diminishes supply. Taking all of these factors into consideration, a major study concluded that without new interventions, a 3.2 million acre-foot imbalance could exist by 2060. That’s the water needed to supply ten million households in the West.

The rapids are roaring. Some of the rafters are arguing with one another. The river guide is trying to keep everyone paddling together. How will we make it through?

First of all we need to understand that the solutions for the next 100 years are different than the solutions from the last century. These new solutions are based on cooperation, and the recognition that the vitality of the American West depends on everyone paddling together. At Arizona State University, the Decision Center for a Desert City is working to bring together scientists with water managers, policymakers, environmentalists, farmers, and other stakeholders to cooperatively develop the solutions, the knowledge, that we need to foster sustainability.

These solutions include managing demand through smart conservation-based incentives: technology and pricing; expanding the reuse and recycling of reclaimed water; developing climate adaptation plans; and fostering more innovative and adaptive institutions; and focusing our water decisionmaking on maximizing the economic and quality of life benefits of each gallon of water invested.

And there is increasing evidence that these solutions are working. Cities across the West are becoming remarkably efficient. The city of for Phoenix for instance has reduced its per capita consumption by 30% over the last twenty years. This allowed the city to add over a million new residents and use the same total amount of water. In the Phoenix region, we now recycle almost 90% of our wastewater, and use that water for producing power, irrigating crops, and watering landscapes.

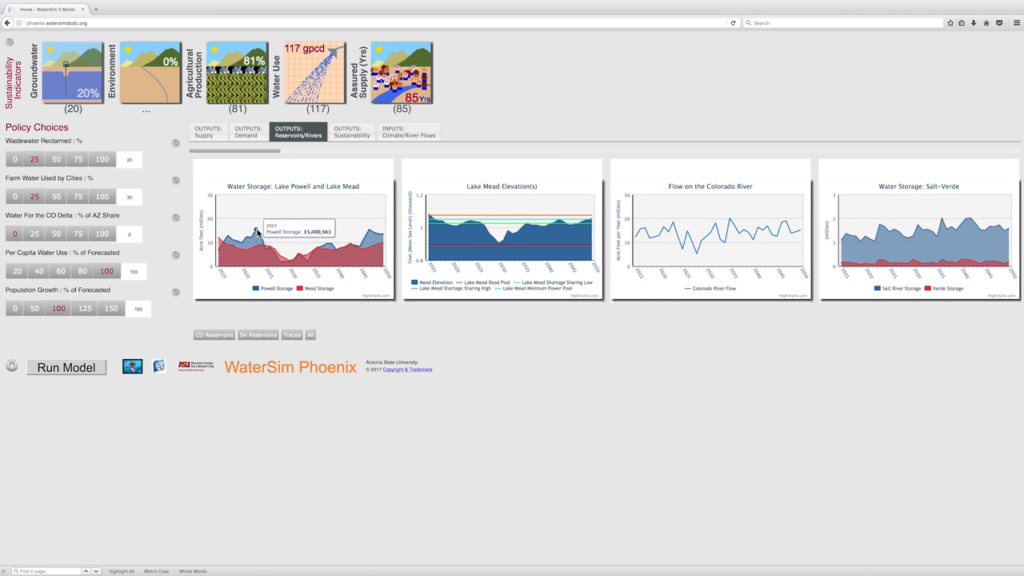

Climate planning is now regularly incorporated into water management across the West. Federal agencies are learning to anticipate and adapt. At the Decision Center for a Desert City, we developed WaterSim. We worked with stakeholders to build a dynamic water balance model to explore how water sustainability is influenced by various scenarios of population growth, drought, climate change impacts, and water management decisions. We’re using this model to test different policies and to encourage collaboration.

We’re becoming more innovative and adaptive in our institutions. Recently the cities of Phoenix and Tucson entered into a water-sharing agreement that will encourage groundwater aquifer recharge in both areas and save the cities millions of dollars. Along with the city of Phoenix, the Decision Center for a Desert City launched the Western Mayors Water and Climate Summit to create a network of cities working at the cutting edge of sustainability and sharing best practices. The Bureau of Reclamation developed the Pilot System Conservation Program to encourage water conservation across the basin, unleashing the power of innovation and entrepreneurship.

And the states are not waiting for a declaration of shortage to occur. The leaders of the states of Arizona, California, and Nevada are working right now to negotiate a voluntary curtailment in advance of any federal declaration, to ensure that we can maintain water in the basin and keep those lake levels above the critical thresholds. This is bold leadership, and the states deserve credit for engaging in these deliberations ahead of the crisis. California has even agreed to take cutbacks in their deliveries to avoid that big boulder in the middle of the river.

Courage, leadership, teamwork. These are the qualities that it takes to run Lava Falls in a river raft, and these are the same qualities that it will take to solve our sustainability challenges in the Colorado River Basin. We’ve made it through some big rapids in the past. But the biggest tests are yet to come. Let’s all pull together, dig those paddles into the water, and have some fun along the way. Thank you.