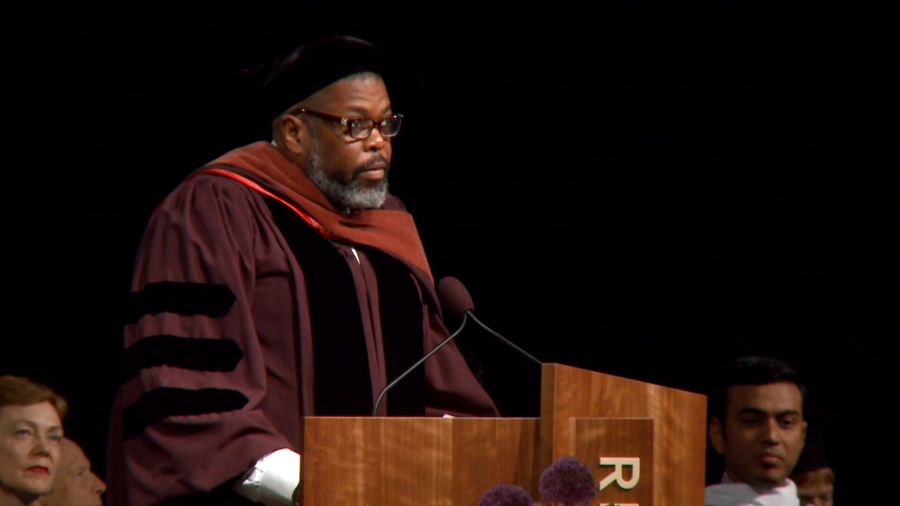

Pradeep Sharma: President Somerson, I have the great honor to present Hilton Als for the honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree from Rhode Island School of Design.

Rosanne Somerson: Hilton Als, in books like The Women and White Girls, and your prolific writing in major publications like The New Yorker, Vibe, The Nation and The Village Voice, you have established an entirely unique voice and become a leading interpreter of American culture. You have collaborated with and written extensively about visual and performing artists, enriching these encounters with your sharp critical perspective, your vast historical knowledge, and your unique gift for tender, nuanced observation.

In your elegant prose and in the way you have cultivated your critical identity, your career has embodied many of RISD’s values: Clarity, curiosity, complexity, and courage, among so many others. You have been remarkably generous with your gifts, sharing your abundant intellect and talent with millions of people, through many platforms, as you will share them with us here today. Mr. Als, we are humbled and thrilled that you’re here today to address our soon-to-be graduates. And now you are going to be one of them. We are pleased to present you with this honorary Doctor of Fine Arts from Rhode Island School of Design

It is now my privilege to invite Hilton Als to address this year’s graduates, their families, loved ones, and friends.

Hilton Als: Thank you so much. If you can’t hear me, just complain. I feel like Erica Badu at the beginning of “Tyrone,” you know? That little riff where she says, “I’m an artist. I’m sensitive about my bleep.” Yeah, I’ll be nice about it.

I want to thank the trustees, President Somerson, Provost Sharma, the incredible team here at RISD, my fellow honorary doctorates, and the graduating class, for inviting me to this incredible event. I won’t take up too much of your time. I’m going to read a piece now that I’ve written for you called “The Case Against Cynicism,” because that’s where we need to be and live. It begins this way.

Just recently, I received a letter. I’m old enough to refer to emails as notes or letters. And its first distinction was its author. The note was written by a fabled American artist, a choreographer I admired from childhood on for her vivid, dramatic, humorous, and romantic dances that had done much to celebrate American form and movement. The way we walk, how we play, what it looked like when one embraced an enemy, or how the atmosphere changed when, as lovers, we parted from one another and walked away.

My correspondent’s name, Twyla Tharp, is as American as her vision, and she is to my generation what Martha Graham was to your grandmother’s, and what Savion Glover is to yours. Her letter contained sentences every artist loves hearing from another artist. “I like your stuff. No agenda. Let’s meet.” One feels alone, and then suddenly not alone, reading missives like that. And as I sat reading and rereading Twyla’s invitation, I could scarcely believe my eyes, I had loved her for such a long time.

I thought of where we all begin, which is to say with a name. And Twyla’s name, what a Hoosier story that is. Before her birth in Indiana in 1941, Twyla’s mother, Mrs. Lucille Tharp (her four children called her “Lethal”) was reading the local paper when an item caught her eye. It said that Twila (with an “i”) Thornberry [Thornburg] had been crowned the 89th annual Muncie Fair Pig Princess. Mrs. Tharp thought that Twyla (but with a “y”) might be a nice name for her eldest child. It would look good on a marquee. She was right.

“Destiny, quite often, is a determined parent,” Twyla wrote in her 2003 book The Creative Habit, “learn it and use it for life.” And by the time Twyla was four, Mrs. Tharp was driving her eldest child to all sorts of lessons all the time. Tap and ballet, piano and sightreading, twirling and gymnastics. These were the tools Twyla would need to build her own house as an artist. Mrs. Tharp knew what that house looked like, but she had never lived in it herself. An Indiana farm girl who had trained to be a concert pianist, she had a family at a time when making work and raising children was not a possibility. Not even an imagined possibility.

My mother, Marie Als, was a determined mother, too. She grew up in Brooklyn during the Depression and World War II, a child of the great West Indian migration that made East New York and Crown Heights and Flatbush different than it had been once. As a girl, my mother loved to dance. From all accounts, she was a fabulous social dancer. My uncle called her the girl of a thousand steps. There she is in my mind’s eye dancing, jitterbugging at the Savoy in Harlem, or dancing a kind of energetic two-step, under the stars somewhere in a world that have yet to limit her dreams, dreams she passed along to her children. But I never wanted her dreams. I wanted her to keep them, use them for herself.

But how could she build her artist house when she didn’t even have access to the information about which tools she’d need to build her own place as a creator? There’s no worse here. Mrs. Tharp, knowing what that house looked like and not being allowed to enter it. My mother not even knowing where that house might be placed, and her place in it.

Sitting in a new place, Twyla’s apartment with its park light and air, I looked at the small stage she built in her living room. And then I looked at Twyla on it, her splayed feet, and as Twyla showed me a bit of business, her eyes were bright with the artist’s way of brightness. “Look at me. Look at me. Do you feel me?” And of course, I saw my mother dancing in that airy apartment, if she’d access to the tools to turn the jitterbug into her own dance.

And as Twyla raised a leg to show me something else with a little laugh, a great feeling rose up in me. And it was the realization that as artists, Twyla and I shared that which all artists share, hope. Indeed, we had been raised on it. It was greater than Mrs. Tharp’s grief about not being a concert pianist, or my mother a professional dancer. Hope was the force that got Mrs. Tharp to see her daughter’s name in lights. And hope was the force that propelled Mrs. Als to carry books home from her many badly-paid menial jobs, jobs in other people’s homes, because her son liked to read and dream, and she liked to read and dream alongside him.

Was I my mother’s art? Was Twyla? And as Twyla and I moved into the kitchen to eat a slimming dancer’s dinner, some sort of turkey thing, a grain thing, lentil soup, it occurred to me further that Twyla and I could hope because we’d seen what it had done for us. We were refugees from the world’s cynicism because we’d grown up in belief and knew, just as our mothers knew, that each act of making is born out of hope because there, in the rank earth where cynicism flowers, nothing grows.

You know that by now, too. All the paintings you’ve made, films you’ve produced, sculptures or environments you’ve created, landscapes you’ve designed, furniture and decor you’ve made happen, exist because you, like Orson Welles, another one of our great artistic forefathers, have what Welles identified in himself: a sentimental attachment to hope, he said. Nothing could tear him or you away from it. Not the kids who tried to mess with you back in grade school and beyond, or skeptical family members who didn’t love you well enough to just shut up and wish you well.

Cynicism vis-à-vis your making will increase as you get out there. The more far-ranging your self-exposure, the more certain people—cynics—will take it as an opportunity to carve you up and dress you in their bitterness. Nietzche thought cynicism balanced hope, but I’m not buying that. Essential to your work as artists is learning to survive. If you don’t, who will tell your story? And anyway, it’s fun to prove people wrong. If Emily Dickinson didn’t insist she was a poet, there would be no poems. If James Baldwin didn’t insist he had a voice, there would be no essays. If Orson Welles didn’t insist on his vision despite industry cynicism, there’d be no Chimes at Midnight. And if Twyla Tharp didn’t believe she could make dances, there’d be no “Deuce Coupe” or “Push Comes to Shove”, or the hundred and thirty-eight pieces she’s completed years after Mrs. Tharp stopped driving her to all those lessons.

From Twyla’s The Creative Habit,

London’s evening standard from 1966. “Three girls, one of them named Twyla Tharp, appeared at the Albert Hall last evening and threatened to do the same tonight.”

So what? Thirty-seven years later I’m still here.

And you’re still here, too. A weird part of your job as artists is building on the fortitude you’ve already evinced is part of your nature. You have to stay put while remaining porous, or open to experiences that may hurt you. Your job, which is not inseparable from your life, is to combat cynicism while remaining open to experiences that are sometimes designed by cynics to hurt you.

So, it’s important that you pay attention and draw sustenance from history, that legion of hopefuls who proceeded you into not knowing, despite cynics. The naysayers who said that Billy Holiday’s way of singing wouldn’t go over. The crap slingers who said Andy Warhol was nothing more than a fancy window dresser.

Those artists have been where you are now, tentative, and hopeful, and looking forward, and looking back as Twyla did, when as a student herself, she looked for herself. Just as I see myself ever more clearly in my mother’s hope. In The Creative Habit, Twyla recalls that

In my senior year, when I was torn between my art history studies and a consuming urge to dance, I used to comfort myself by camping out in the dance collection of the New York Public Library. I’m not sure what motivated me to do this. The New York Public Library houses one of the world’s great dance archives. I asked the curator to bring me photos of the women pioneers of dance. Isadora Duncan, Ruth St. Denis, Doris Humphrey, Martha Graham. I could read their movement vocabulary from these photographs, keeping what was useful and ignoring what wasn’t. Once they were locked in me, I was free to call on them any time. If one day I was stuck, I could ask myself, How would Martha move? or, What would Doris Humphrey feel like? In a sense, I was apprenticing myself to these great women. That’s what I was doing in the archives. Shadowing my predecessors. This is how you learn your ancestry.

Your ancestry includes your version of Mrs. Tharp and Mrs. Als. And sometimes your ancestry shows up when you least expect it. In letters addressed to people you do not know, but who will write to you, too, because that’s what the true artist shares. The freedom of faith. The boundless skies that roll and float above your tremendous and real and necessary hope, as you build your own artist’s house out there for all the world to see. Thank you.

Further Reference

“Embracing the Asterisk” at the RISD web site