I’m Johannah. On Twitter, I’m Johannah with eight Js, and I’m actually not talking that much about bots, [inaudible] has an intuitive sense of what they are and what makes them fun. So instead I’ll be talking about how that relates to wacky inventions and wacky inventors, especially at the turn of the 20th century. Mostly I’ll be talking about Rube Goldberg machines and also Heath Robinson machines, which are the British version. So here’s a quote:

The Goldberg inventions countered the corporate impersonality; they are the whimsical solutions of an independent gadgeteer bent on asserting his right to dream.

Peter C Marzio, Rube Goldberg: His Life and Work

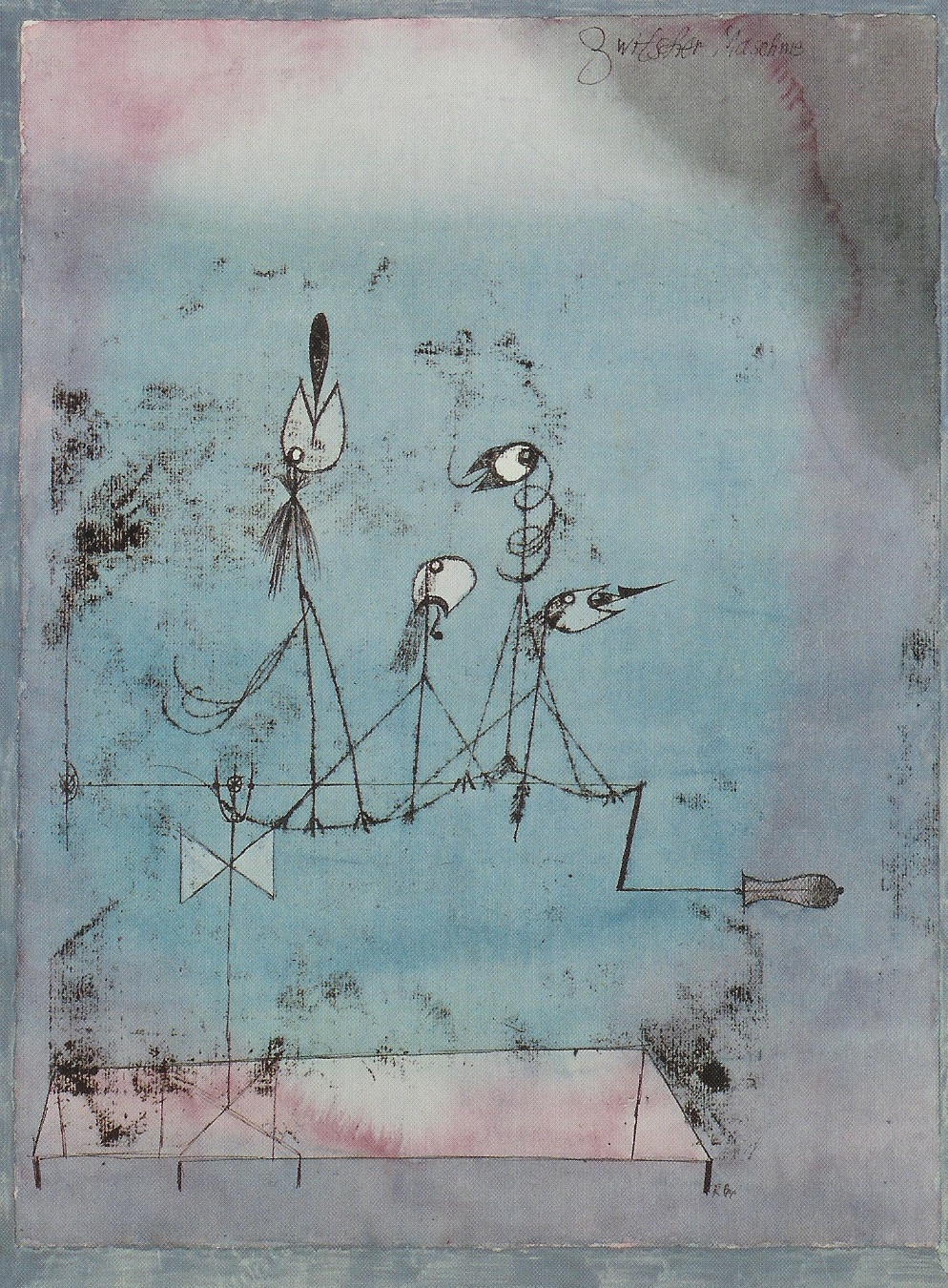

Paul Klee, “Twittering Machine (Die Zwitscher-Maschine)” (1922)

That reminded me a lot of you guys. Likewise, the “Twittering Machine” is actually the name of a painting by Paul Klee and the art critic K. G. Pontus Hultén called these the “modern machine” and also the “mock machine,” and said they’re machines that look like machines but accomplish nothing. That is from the 1968 MoMA exhibit “The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age.”

I’ll come back to this later, but just to quickly run through what bots and Rube Goldberg machines share:

- They’re funny.

- Justifies its existence when it works, not because it’s solving anything.

- Absurd, meant to be plausible but not realistic. Mimesis is not a goal.

- Deliberately dumb compared to cutting edge technology.

- Popular while historically on precipice of machine-danger. (For Rube Goldberg that refers to the atomic bomb. For us I guess it’d probably be AI, or drones, or I don’t know. Whatever you want.)

- And fixated on the possibility that there is an animal (not a ghost) in the machine. (It’s complicated, I’ll get to it later.)

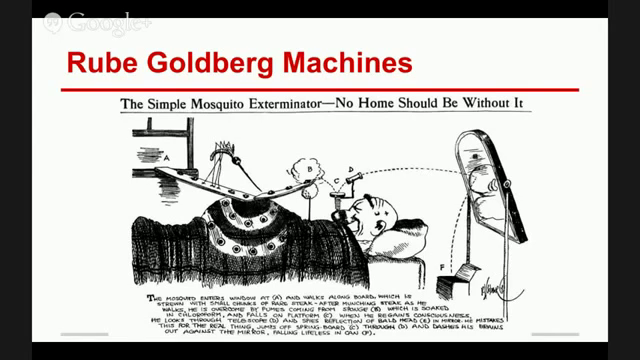

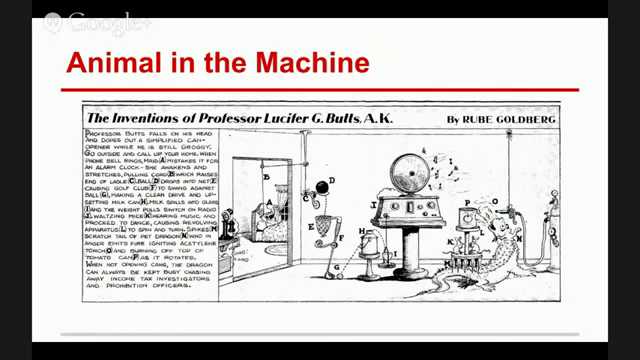

This is a Rube Goldberg machine, in case you don’t know, and this is one of his earliest machines. It’s called The Simple Mosquito Exterminator. You can see it’s complicated, but mechanical and purposefully not straightforward and efficient. These Rube Goldberg cartoons started in 1912, a daily strip was added in ’24 and continued until ’34. He continued producing invention cartoons until ’64, and the inventor in the cartoons is called Professor Lucifer G. Butts. The “G” stands for Gorgonzola. “Rube Goldberg” didn’t become an adjective until ’66.

Just to get an idea, this is a Heath Robinson contraption, again just the British equivalent. I’ve heard that there’s a Swedish equivalent as well. They were both working [around] World War I, World War II. It was just in the air.

Goldberg was very influential. You can’t see because this is just a picture I took of a book because I couldn’t find it online, but this is from Rube Goldberg’s living room. It includes the Gershwins, the Marx Brothers, Three Stooges, Jack Duncy, Fanny Brice, several Ziegfield girls, and not in this picture, but he was also really really good friends with Charlie Chaplin.

These machines are not like other machines, and again at this point you should just imagine I’m also talking about bots even though these specific quotes have to to with Rube Goldberg or Heath Robinson machines. So

The essential quality of a Heath Robinson machine is that it has its own inexorable interior logic…When each time the machine shows that it works, it justifies its own existence, and the jobs of the huge numbers of staff requires to operate it.

Maybe not huge numbers of staff in bots’ case, but certainly there’s a lot of staff going on behind computers, and everybody’s working together. So in that sense there’s a huge staff.

And this is actually about Duchamp:

By demonically distributing complete clues of representational deception and an abstract pattern that is never quite “abstract,” Duchamp makes sure that his refractory productions frustrate their own illusions of integrity by being neither true nor false except to their own rationale of divisive anamorphism and self-reflexive plot.

Lawrence D. Steefel Jr., “Marcel Duchamp and the Machine” [PDF]

It means the same thing as [the previous quote].

The point being that this isn’t just some random thing about Rube Goldberg machines, it’s also about changes in art. It’s a broad pattern that happens whenever there’s a major technological shift, at least for the last hundred years. You get these useless machines that self-justify.

Again, they are totally inefficient. These are both Heath Robinson contraptions. The one on the left is for pouring water on a cat, and the one on the right is for taking a selfie, so I thought you guys would appreciate that.

This is another Heath Robinson contraption, but I’m showing this to show how this is a response to the efficient machinery of World War II. This was for pouring hot water on German soldiers, and as you can see it’s very inefficient, very low-tech.

Men around the department who have trouble puzzling out something in the blueprints yell out after referring in some manner to the Lord, the Devil, or Rube Goldberg…Some man may yell out, “This **oo**!!?! blueprint looks like something Rube Goldberg made!” Or, “If Rube Goldberg were here, he could tell us how this engine goes together.”

Anonymous engineer from Detroit

One of the things that’s really interesting about this phenomenon is it’s appropriated by big business, even though it seems to be resisting the ideas behind big business. This is a quote from an engineer in Detroit. The censoring is in the quote, I didn’t put it in there. That’s what those stars and Os are. They really adopted him as an icon, and just to give some background of what was going on at the time, invention around this time became corporate instead of individual. This was around 1920, as Bell Telephone, General Electric, and Westinghouse came to prominence, and Rube Goldberg said “with few exceptions no single person can stand out as the inventor of any great mechanical appliance.”

Also, Professor Lucifer G. Butts really hated big business, even though he was adopted as an icon of it, and I’m quoting from Rube Goldberg’s biography from this guy Marzio. He says

Butts was an emotional guy who condemned the big wholesale laboratories for ignoring the intimate needs of the people. “The social demands are growing more urgent and nothing is being done about them,” the Professor shouted one afternoon in 1928. One of Butts’ greatest machines was the self-destroying memorandum pad. As soon as someone jots down a note, the pressure of the pencil squeezes a small accordion, which frightens a lightning bug. As the bug flies up, it ignites a row of candles on the edges of the memo paper. The candles burn paper and the bug, still exhausted from his flight, pants heavily and blows out the candle, leaving a fresh piece of white paper for the next notation. According to Rube, Butts drew a plan for this device, but “representatives from white collar associations around the world hired crooks to steal Butts’ only copy.”

So, Butts and big business were enemies in this mythology even though big business adopted him as an icon.

The machines are deliberately dumb. That’s an ad from the “Ideal Home” exhibition in ’34, which is a British fair. Heath Robinson created a full-scale home called the Gadget Family for the 1934 Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition at Olympia, where it stood physically opposite the modern stainless steel Staybright City, and Daily Mail wrote

At the heart of the exhibition, set where it could poke a badgering kind of fun at the exhibitions of inventions the world has ever seen before the Heath Robinson house turns the creaking wheels of its wood and spring machinery, yet like everything else in Olympia the grotesque satire on an ideal home works perfectly.

So again, even at the time these were thought of as low-tech and stupid or dumb machines, sort of like how bots are not meant to be realistic AI and they’re supposed to sound flat or stupid or whatever.

Also, they are not at all oppressive. This is a still from Modern Times; that’s Charlie Chaplin at the feeding machine. Machinery obviously has the capacity to be very frightening, but Rube Goldberg machines are fun, and breakfast actually is a theme of Rube Goldberg machines.

On the left that’s a Heath Robinson pancake-making machine, and on the right that’s a still from Pee Wee’s Big Adventure. I can think of a billion examples of the breakfast machine. It’s a huge trope pre-dating the 20th century even, and I think it’s an example of something that’s very fun. Bot culture is similarly fun. I don’t think there’s a breakfast equivalent, but I thought that was a cool trope to point out.

It also reminds me of bot culture’s love of schoolmarmish aphorisms. I think that’s maybe a way that you can compare the oppressiveness of mechanical machines from the Rube Goldberg era to the oppressiveness of text on the Internet constantly advising you, the oppressiveness of intelligence, whatever.

This one I haven’t really fully worked out yet. We can talk about it later or on Twitter. Something that’s really interesting to me is obviously a lot of bots have a feeling of there being a ghost in the machine. But a lot of them don’t feel like there’s a ghost in the machine, they feel like—you get paranoid that there’s an actual person there and obviously that came to fruition with @horse_ebooks. I notice it a lot with Olivia Taters. And in Rube Goldberg machines yout get a lot of that—I chose this one because there’s a dragon there. Rube Goldberg said that he often has to have emotions and animals in his cartoons.

When I have a goat crying in one of my cartoons, I have to give a satisfactory reason for having it cry, so I have someone take a tin can away from him.

Rube Goldberg

He also has the idea of something called [yok yoks?] which are little bugs that make machines mess up, which is—I don’t know if intentionally or not—but is an updated version of the Yahoos in Jonathan Swift.

This is the part that I feel least confident about in terms of relating Rube Goldberg machines to bot culture, but I’m just throwing it out there.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8aI9_Nv5rz4

I wanted to point out again, even though I’ve talking about Rube Goldberg machines and Heath Robinson machines, it’s not specific to those two moments even though I think of those as the wackiest machines, and I think of bot culture as being very wacky. Useless machines also came to prominence in modern art. That’s Duchamp, obviously. I already showed you the Twittering Machine from Paul Klee.

Here’s another example of a useless machine, less famous, but just to show that’s it’s not just Duchamp doing it. This is “Fakir in 3⁄4 Time” by Lucy Jackson Young and Niels O. Young, and this is a machine that makes a rope stand up on its own.

To return to that slide I showed you guys before, what bots and Rube Goldberg machines share. They’re funny; justify their own existence when it works; Absurd, deliberately dumb; popular while on the precipice of machine-danger; and fixated on the possibility that there is an animal, not ghost, in the machine

And that’s all I got.

Darius Kazemi: We do have time for a few questions or comments. We’ll start in the room and I’ll take a look at IRC and make sure we’re getting that representation here, too.

Audience 1: The animals trapped in the machine, would you relate that to Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and distributed labor applications like that?

Johannah King-Slutzky: Definitely. That’s a great point. Something I forgot to mention, that a lot of these bots do literally use human labor, because they form the corpora for the way we’re talking, and also bots respond to people all the time. So I think it’s the same phenomenon definitely. But a little different because Mechanical Turk is so menacing and it’s sort of uncanny, which is at the crux of the ghost in the machine as well. The dragon in that cartoon I showed of the Rube Goldberg machines is not at all uncanny; it’s very soothing. So I have a hard time distinguishing between those two ideas all the time.

Audience 2: Building on that, though, I wish Rob [Dubbin] was still here, because he’s a friend. I simultaneously love Olivia Taters and I’m growing to dislike her a lot, because she’s built off of the body of work of teen girls. And I think it’s explicitly girls because of the words that he’s chosen to scrape from and the body of text that he’s chosen to build from. And it’s supposed to be like, “Oh teens! Oh well.” But it’s explicitly like “LOL teen girls!” and, “Check out this teen girl! She’s the most incredible teen girl.” There’s actual incredible teen girls. Did we need to build a fake teen girl for everyone to admire on Twitter? Because there’s a bunch of those and they talk about One Direction more than Olivia does, and they talk about actual teen girl things. So if Olivia is the “dad greatest hits” of teengirl-dom because she doesn’t talk about any of the things that actual girls like, she just talks to you thirty-something adults sometimes. It’s this weird decontextualized experience of what being a teenage girl in America is. It lets you feel like you’re watching a teenager without ever having to actually… So in that way it’s like but maybe she’s real, this is getting too creepy. Sometimes she’ll actually talk about hairstyles. Sometimes she’ll express an opinion about something and that’s like, “Oh my god, did someone actually write that? This seems too close.” And it’s like the parts where “Oh, it’s getting like a person.” But then sometimes, “Oh she’s funny.” And I’m like yeah she’s funny. I don’t know [crosstalk]

Joel McCoy: There was the follow a teen [inaudible] a little while ago and that’s legitimately weird and creepy. [crosstalk]

Audience 2: Like “adopt a highway.”

Joel: Follow the teen and just don’t talk to them, because that would be weird. But what you can totally do is subtweet what your teen is tweeting about to your adult friends. It’s that one layer of abstraction where it’s like at least you’re not actively harming a real teen despite [crosstalk]

Audience 2: Just carry this egg around for two weeks.

Erin McKean: No teens were harmed.

Audience 2: It seems like this very odd thing to do where it’s like learn to listen to women? No. Build a bot. Build a bot. I think it speaks to some of that, like sometimes she seems real because her text is real. It comes from young women and the uncanniness there. Same with distributed labor. The uncanniness makes you aware that there are millions of people on this planet, alive at the same time that we are, and they’re active. And when they’re active on the same button, shit happens.

Darius: We also have a question from IRC asking if there are bots based on Amazon’s regrettably-named Mechanical Turk service. I know of art—

Audience 3: The sheep.

Darius: There’s Clement Valla. He sent a line through the service asking people to retrace a line over and over again and you can sort of create this animation or collage of it moving and mutating and that sort of thing. I believe he’s done other work with the service as well. I don’t know if there are any— It’s hard to to Twitter bots because it’s not a real-time API-based thing. You put a request out and then you wait for things to come back. I think the way that I would approach it if I were to do something like that would be to make a bulk amount of requests and build a corpus that way, and then tweet from that static corpus. That seems to me the only way that you could really build up a bot based on that.

Audience 3: There’s a [inaudible] project by Matt Richardson called “Descriptive Camera.” It wasn’t a Twitter bot, it was a physical installation. But it was a little hardware camera he built with Raspberry Pi inside with no viewfinder. When he clicked the button it would take a picture, not show it to you, send it to Mechanical Turk, have a Turk job where somebody would describe what they were seeing in the picture, and you’d get back two sentences with a description like five minutes later. It’d be like, “This is two people standing in front of a brick wall and one of them’s kind of smiling and the other one looks distracted.” That would be a kind of natural Twitter bot. He was able to get sub-five and ten minute latencies for a small task like that.

Further Reference

Darius Kazemi’s home page for Bot Summit 2014, with YouTube links to individual sessions, and a log of the IRC channel.

Johannah’s piece “Robopoetics: The Complete Operator’s Manual” at The Awl is not about Twitter bots, but also worth a look.