Jonathan Zittrain: Hi. My name is Jonathan Zittrain. I teach here at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. Sounds more normal every time I say it. And first an administrative announcement, we are being recorded. Not just by the usual panoply of suspects but by intention. And we are live webcasting. So be aware that anything you say will be recorded forever and might be used against you. I always like to bring out the Miranda warning.

It’s my pleasure to introduce Kendra Albert for today’s talk. I’m so pleased to have a chance to introduce my colleague, friend, sometime mentor Kendra. When I first met Kendra, they had been studying the Daubert case and its relationship to the Fry standard of evidence in the federal courts. Which was a little surprising because Kendra was undergraduate and not a law student or law graduate. And Kendra carried on that tradition through a summer at the then Berkman Center program working not only on our OpenNet Initiative but later our H2O project for open casebooks. And they took not only to helping to format the cases and such and doing some basic research, but started editing the cases and then reading all of the cases for a course on torts.

For those of you who are law students, you’ll realize that voluntarily reading all the cases for a course on torts is an extraordinarily unusual thing for somebody to be motivated to do. And I think that did inevitably, despite Kendra’s efforts at times to avoid it, point Kendra towards law school. Which to our great fortune Kendra attended here.

And while here, for those of you again thinking about how to be involved in cyber-related topics, Kendra punched a ticket in so many different wonderful places. The Public Citizen Litigation Group, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and an unlikely third in that triumvirate, Cloudflare, the organization that will help you avoid getting DDoS’d when you least expect it. It will tell you you’re going to get DDoS’d and then you’re DDoS’d. It’s also a good opportunity to thank Cloudflare for their pro bono support of our Perma project. Cloudflare, we love you.

And it’s interesting that while working there, Kendra took up an examination of some of the boilerplate legalese passed around like Christmas fruitcakes from one company to another without attribution. Is that still a good reference, that the fruitcakes just get passed on because nobody else wants to eat it but they’re still an appropriate gift? And they never expire. And the same is true of legal boilerplate.

But then Kendra actually decided to read it. And think about how it might apply to not just terms of service of the usual sort about you know, if you do something to the company then you’re warranties are void, or whatever it usually says. But rather what is the role of the company in trying to enforce basic humane behavior among users of a service for which otherwise the company might prefer to be invisible? And to what extent can that be governed by boilerplate, to the customer, to the company itself inheriting that boilerplate from somewhere else? And to what extent is it a challenge to every company to actually sit back and think about, as Terry Fisher would say, what are the prerequisites for human flourishing? And how should we embody that in our terms of service?

And I think, not to anticipate too much Kendra’s talk, the answer may lie disarmingly closer to the second answer than to the first. And that of course poses some really tough questions for the companies and for all of us as we try to put companies into a role of policing some of the most profound questions that face us in the digital space as people communicate with one another, get into conflicts, troll one another. How to mediate that is just an unanswered question. Nobody has figured this out yet. And I’m hoping out by the end of this talk we will have done so thanks to Kendra.

So with that modest introduction, I turn it over to Kendra for [their] valedictory lap back at the home team after [they] had gone to the Zeitgeist Law firm, a technology-oriented law firm that’s thinking about this stuff. Kendra, take it away. Thank you.

Kendra Albert: Thank you. And Jonathan, that was an amazing introduction. And I’m not sure the talk lives up to the promise of the introduction, but maybe it does something different and hopefully that’s how all good talks work, I suppose.

But before I get started I want to just take a moment to express solidarity with Unite Here Local 26, who are the folks who are protesting outside. I think it’s important even as we problematize and deconstruct notions of free speech, to recognize that it has an important role in some of the things that are most valuable, including ensuring people who represent workers can strike and be heard. So, I’m about to do a lot of things beating up free speech, but first I want to recognize its role and sort of express solidarity with them.

So, when I use the phrase “legal talisman,” what I mean to suggest, as Jonathan sort of alluded to, is that I’m talking about a legal term of art, a legal word, that’s out of place. And it’s invoked to make or justify substantive decisions that don’t involve formal legal process, right. Decisions that are made in a way that does not involve the court system, does not involve legislatures, does not involve administrative procedures. It’s a legal term that shows up in sort of the places you would least expect it, the arguments that you would least think that it’s justifiable.

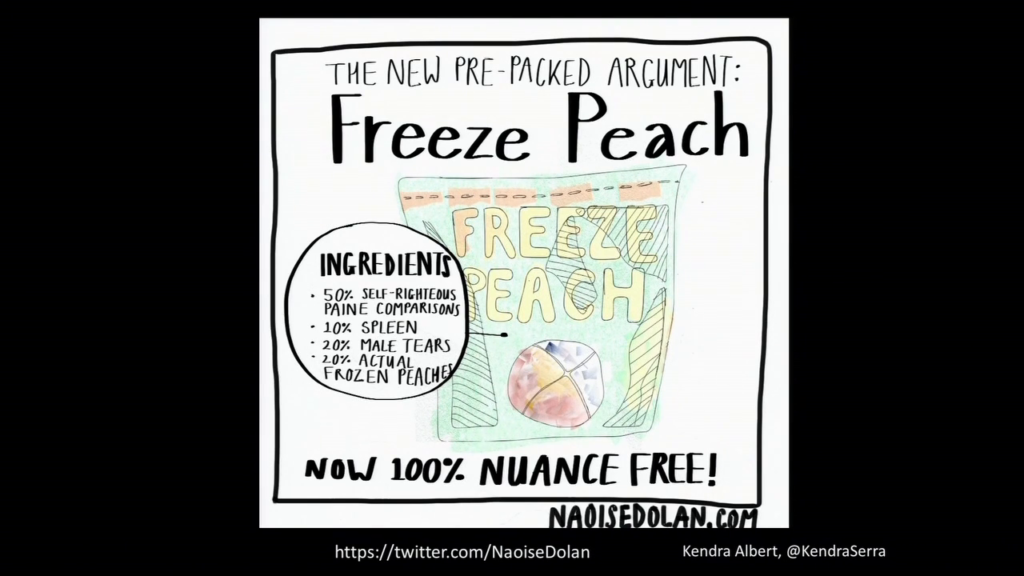

Naoise Dolan, “Freeze Peach”

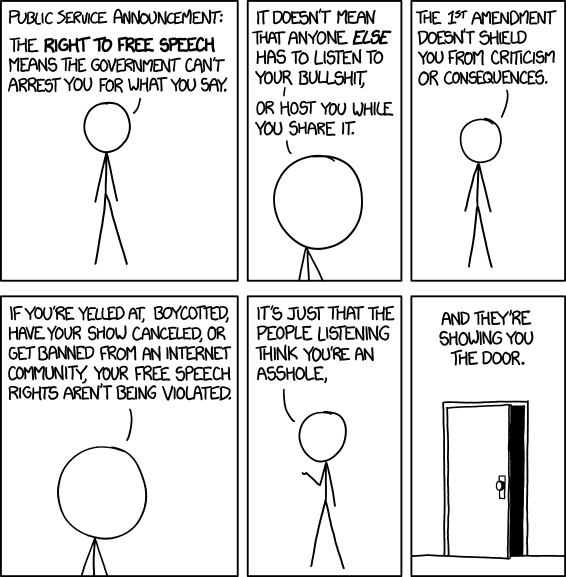

And I started looking into this, as Jonathan said, because I was spending a lot of time thinking about online abuse. And often what you see in online abuse is legal talismans everywhere. The most common of these, as pointed out by the work of Sarah Jeong and others in deconstructing the role of speech arguments, is free speech, or “freeze peach” as it is sometimes known. And you can see both this comic as sort of a funny a joke about the role of free speech online, but this idea of nuance-free or self-righteous Paine comparisons, really points to this idea that free speech has come to mean something in online discourse that is separated from the First Amendment reality, or from the law. That it’s invoked in places that we might think of as rather unlikely for a First Amendment rhetoric.

And so if we imagine why that happens. If we imagine the magical powers that the free speech talisman can embody, it sort of wards off regulation, responsibility, and liability. It’s ideal for use in the United States. And it’s crafted to be especially effective to responding to claims of rampant on-platform abuse. Like, what does invoking the term free speech allowed us to do? Well, it allows us to shift the conversation in a way that’s really meaningful, and in a way that changes our relationship to regulation and liability.

Randall Munroe, “Free Speech”, XKCD

Of course, I’m not the first person to point out that the use of the term free speech is not really legal. I think the now-obvious counterargument is this XKCD, which actually not new, which invokes the legalistic responses to free speech. Well, it’s not the government doing the censorship, or that platforms are not government speakers, people don’t have to listen to you. That’s all the sorts of thing that come along with these invocations.

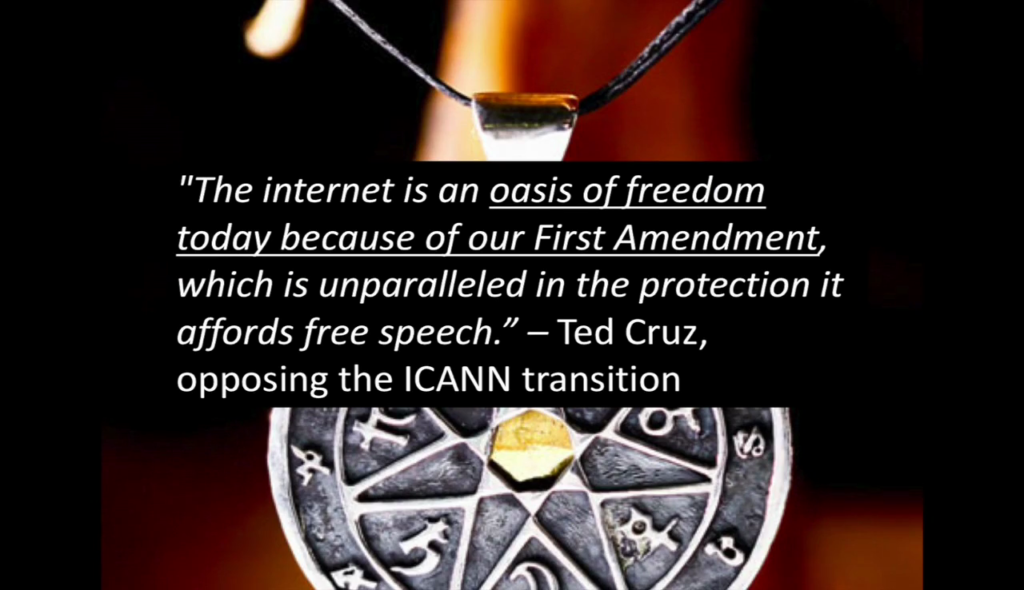

And it’s not just confined to trolls online. This is our friend Ted Cruz, who was talking about the ICANN transition, which was the process by which the US was ceasing its contract with the International Assigned Corporation of Names and Numbers. (I probably got that wrong, sorry.) But anyway, what he says is that the Internet is the Internet. It’s an oasis of freedom today because of the First Amendment? Which is a sort of strange claim, because I think most folks who are actually involved in ICANN would argue that although First Amendment principles may be involved in decisions that ICANN made or underlying platform or technical thoughts, the First Amendment was not like, super involved in the ICANN contract.

Before I go any further, especially since Jonathan mentioned Cloudflare, I want to say this is just me talking, not my employers or my clients.

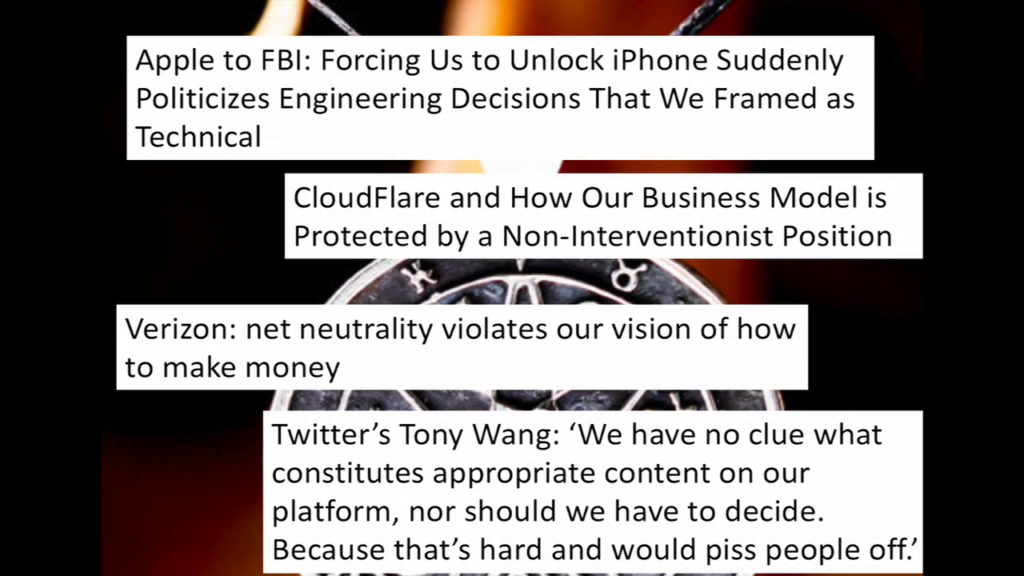

So, some other places we see free speech are in corporate responses. So, “Apple To FBI: Forcing Us To Unlock iPhone Violates Free Speech”; “Cloudflare and Free Speech,” which is a blog post that Matthew Prince, the CEO of Cloudflare wrote about how they dealt with Islamic terrorism and radical Islam and jihadi posts on the platform; “Verizon: net neutrality violates our free speech rights,” which was one of their responses to the FCC’s net neutrality rules; and then perhaps maybe the most famous quote of these four is from Twitter’s Tony Wang, where he said, “We are the free speech wing of the free speech party,” something I’m sure he regretted for pretty much the rest what came after.

And some of these are actually about legal proceedings. Apple to the FBI, and Verizon are about court proceedings where they were making a First Amendment argument about what they had the potential to do. But “Cloudflare and Free Speech” and Twitter’s free speech position are not. This is not in reference to a particular court proceeding. This not because they’re putting forward an argument about their particular liability or lack of liability or how they should necessarily be regulated. In fact, it’s just a shorthand. It’s a reference to a body of knowledge that’s stored elsewhere. And it’s a shorthand for a bigger, more complicated set of ideas, a set of rehearsed arguments about like, free speech, and the marketplace of ideas, and allowing everyone to speak, and the heckler’s veto, and sort of this whole long set of things that you might hear if you sat in on a First Amendment class or read a First Amendment case.

And it’s also a way to make things feel a little less arbitrary, right. If Twitter had said, “We take down whatever we feel like,” that maybe would present a less compelling statement of their position on the subject, even if it was just as true as, “We are the free speech wing of the free speech party.”

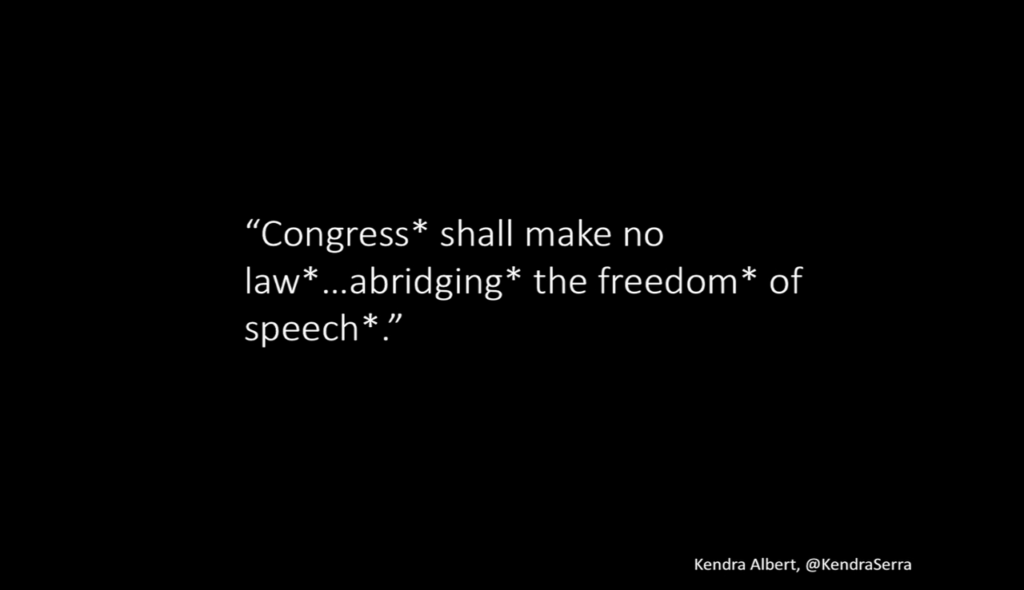

Legal talismans also avoid definitional problems. They allow for us to look at this body of law as a way of understanding what exactly is going on. But with it comes its own problems. So, this may be familiar to most of you as the text of part of the First Amendment, which says “Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech.” Of course, the reality is that Congress makes law abridging the freedom of speech all the time. And so when we look at what this means in practice—

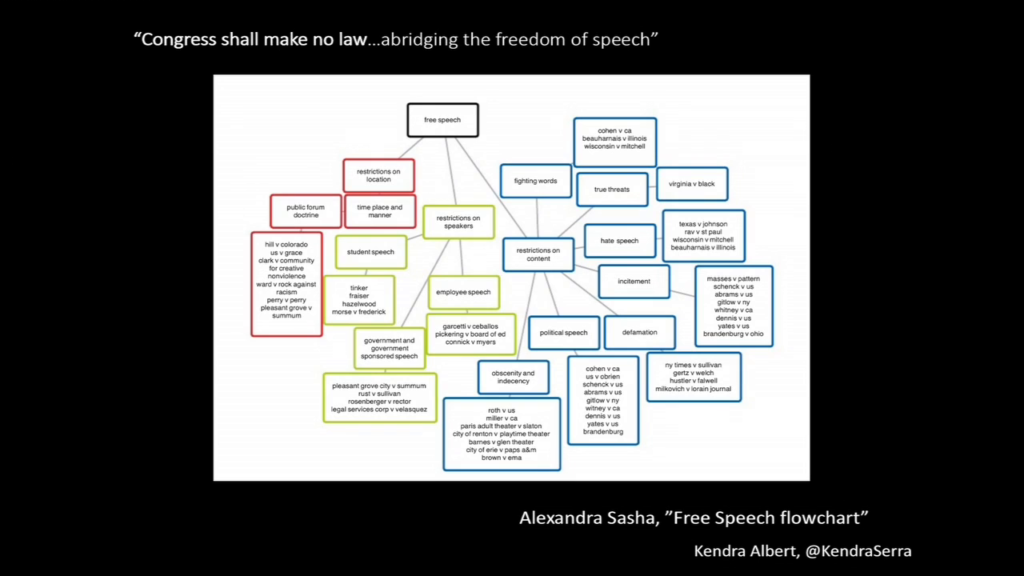

Alexandra Sasha, “Free Speech Flowchart”

I actually stole this outline from a law student, but I think it’s actually a very powerful illustration of all the things we have defined as not speech in order to abridge them. All of of the things that we claim are lower-value speech like commercial speech or employee speech. All of the things we claim are not speech at all: defamation, true threats, incitement.

And how really, this is kind of much more what the First Amendment looks like. There’s an asterisk after every word, with which comes a very long set of definitions of what that means. Like, even “Congress” really also means “…and the states,” right, because of the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments. So when we unpack the meaning of these words, we understand that they actually have all of this context, and all of these things that come with them that aren’t necessarily obvious from the face of the Amendment.

Moreover, and to reference the XKCD again, legal talismans invoke the power and obligations of the state. And I feel kind of silly saying this because it’s so obvious. Like, “when we talk about law, we’re talking about the state.” But I mean, perhaps obviously, platforms don’t have the same obligations to their users that the state has to its citizens. Terms of service are not constitutions. And for the most part, platforms don’t grant users positive rights. And so when we think about the legal frameworks that take into account state power and state constraints, that’s what all of those asterisks in the First Amendment are about. State power, state constraint, how do we think about the relationship of the state and the power dynamic with people? That’s why we have a First Amendment in the first place. We have to understand that law exists in a world where the actor that’s enforcing it is the state.

And sometimes users might want those state-like restriction in the context of platforms. If you believe that use of Twitter is so fundamental to your identity that actually you want it to be treated like a utility and you want due process for getting blocked, then maybe you actually would love all of the sort of restrictions and the costs of the First Amendment that come along with the use of these words. But sometimes users definitely don’t want all of the same things that we want from our government when we’re thinking about our online services. Or all of the same protections for particular people that we want from the government.

So that’s how I’m defining a legal term of art out of place, invoked to make or justify a substantive decision that do not involve a formal legal process. And I’ve said a lot of things about the First Amendment because I think for many people it’s the most tangible, easy to think of way in which this manifests, right. We’re used to the idea that these legal obligations… That people talk about the First Amendment and free speech independent of the actual legal obligations or legal content of those words.

But what I’m about to do is to apply critical legal studies principles to a more specific legal term in the regulation online spaces. So, critical legal studies, for those who aren’t aware, was a legal movement that concentrated on sort of unpacking some of the baggage that these words come with. Most famously, one of the practitioners was Duncan Kennedy, who taught here for a very very long time. But other people from Martha Chamallas to Derrick Bell have all used the tools of critical legal studies for feminist pursuits, for queer pursuits, for critical race theory pursuits, in order to defamiliarize the familiar. To take the words that we think we understand and to show us how we really don’t understand them at all.

And so when I talk about something like defamation, I think it’s really worth defamiliarizing. Because to most people, defamation means saying nasty, untrue things about people is illegal. Like if we want to talk about the most basic definition you could possibly give, that’s the best one I’ve got. I tried to make it shorter and I think I need all of those words, or about a person, even.

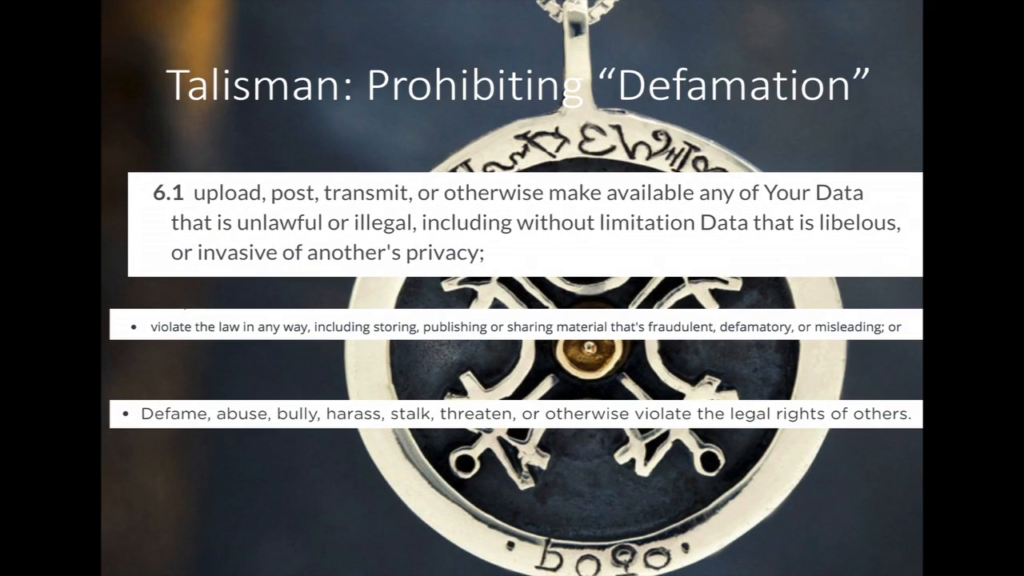

But it shows up everywhere. The first one of those is the terms of service of Slack. So if you have ever said anything defamatory about anybody on a private Slack, that’s against their terms. The second one of those is Dropbox. So, no defamatory material in Dropbox. And then the third one of those, perhaps maybe even most ironically, is Yik Yak. So, you’re not allowed to defame people on Yik Yak, which as folks may know is a sort of service for people to anonymously comment on things that was primarily used by college students. I’m sure Rey Junco is probably turning over…like, just had a The Force moment in Indiana as I characterize it that way.

But the legal standard for defamation, to do my best at putting it slightly more precisely, is that the defendant, who is the person who you’re suing, published a statement. The statement is about the plaintiff. The statement harms the reputation of the plaintiff. The statement was published with some level of fault, which depends on who the plaintiff is. And the statement was published without some privilege.

Now, even that, a slightly more precise definition, is hard. This is William Prosser in Prosser and Keeton on the Law of Torts. And what he says—which you do not need to read, you just need to take my word for it that an old white dude who’d spent a lot of time thinking about torts also thinks defamation is really complicated and difficult, and that we’re really bad at it.

But defamation’s gorgeous traditional design hides deeply sexist, racist, and whorephobic (which means anti sex worker) connotations. The reality is defamation is a talisman. And I mean it as a talisman because the actual analysis is so legally specific as to be unactionable in a practical matter during a content review. It is incredibly difficult for the sort of content reviewer that we think about Facebook or Twitter having, the clickworker in Malaysia who’s trying to figure out whether something is okay or not okay, to figure out if something’s defamation under US law. That’s just not a thing they could actually possibly do. In part because truth is an absolute defense, so you have to know whether the thing’s true or not to know if it’s defamatory.

But the history of defamation is pretty damn sexist. In England, under the under the Slander of Women Act of 1891, female plaintiffs that alleged slander for words that impute unchastity or adultery need not show others reputational harms. And that law was repealed in 2014. Which like, yay for that, I guess. But 2014? And this historical context is not just unique to England. Defamation law in general is deeply invested with notions of binary gender and appropriate roles for women. In fact, many of the first defamation statutes in the US specifically noted that impugning on a woman’s chastity falsely was per se defamatory. And this is why I say defamation law is whorephobic. Because it assumes that being called a sex worker is inherently harmful to someone’s character.

It’s sexist in practice and sexist in theory, because the reality is that even if the statutes are not sexist on their face, when libel and slander actions are brought by female plaintiffs they are more likely to succeed if they are talking about things that are in the private sphere, like accusations of being unchaste as opposed to talking about their business role. So when we see defamation law in practice, it enforces a sort of sex segregation of roles for women.

Oh, by the way. I didn’t add this to my list originally, but it’s also really homophobic. In 2012, New York finally overturned the law on its books that suggested that being called gay was per se defamatory.

And so when we look at histories of how this plays out, you can see this is Virginia da Cunha. She’s an Argentinian entertainer, and she won a lower court ruling against Google for search results for her name that led to porn web sites. We can see that it actually does play out as defamation law having a focus on women’s chastity as a successful model for legal intervention. And so the moral of the sexism story is that defamation can work for you as a woman so long as you’re concerned about your chastity, but much less so if you’re concerned about your business reputation or any of these things that involves sort of public sphere roles.

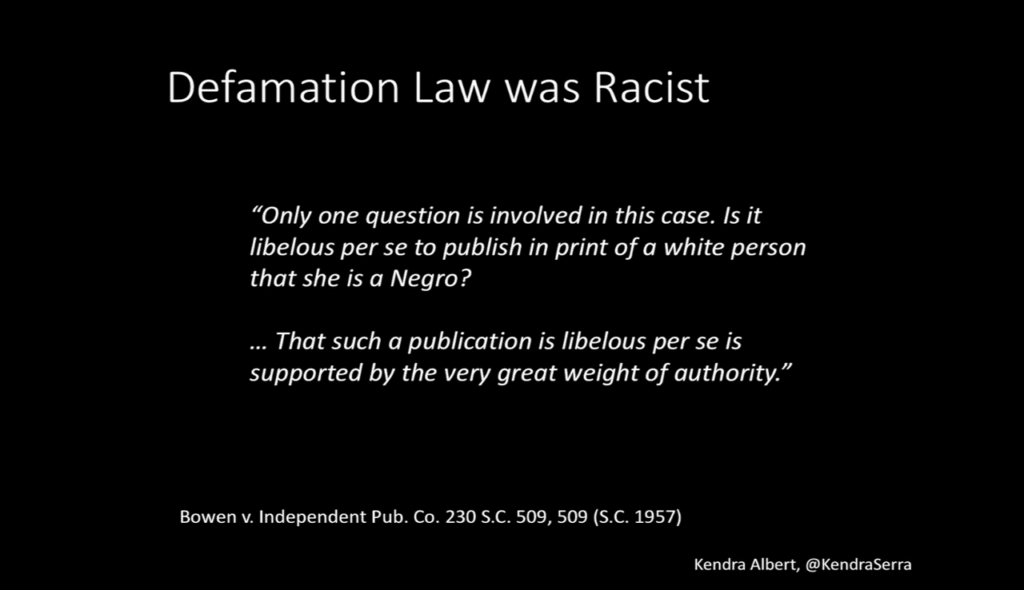

As if that wasn’t enough unpacking or defamiliarizing, we can also talk about the ways in which defamation law is racist. Was racist and is racist. So, defamation per se by racial misidentification, which is if you call a white person black that is per se defamatory and harmful to their character, was the law in many parts of the US up until really really recently, which is the sad part. The tort was analyzed by John C. Watson in his landmark article “Defamation by Racial Misidentification: A Study of the Social Tort.” In it he talks about many things, but this case really stuck out to me from 1957 in South Carolina, which is, “…is it libelous per se to publish in print of a white person that she is a Negro? … That such publication is libelous per se is supported by the very great weight of authority.”

So, facial racism, facial sexism, facial whorephobia. Also, you get all be inherent structural problems of the rest of civil litigation, right. Just because a law is not discriminatory on its actual face doesn’t mean that it doesn’t end up being discriminatory in the way it’s practiced. So, what we know about the structure of civil litigation is that it favors the rich over the poor. That it favors, in the words of Marc Galanter, repeat players over one-time litigants, people who are familiar with the legal system and who understand how it works. And it favors, frankly, people who are considered more likeable by juries. Defamation, as I said before, is really fact-specific. If you end up going to a jury trial, understanding that sexism and racism are still things within the United States, we have to look at how likely a black woman plaintiff who’s suing over her business reputation might be to succeed versus a white male plaintiffs who’s suing over his business reputation. So, people from historically marginalized groups or people who are seen as reaching above their station are generally not necessarily likeable by juries.

So, I want to come back to this, because it’s sort of funny in one way that these terms prohibit this kind of material. But at the same time, I’d like to think that if Slack understood what the history of the term “libelous” was, that maybe that’s not exactly how they would choose to frame their terms of service.

But the reality is that this isn’t just about defamation. Legal talismans whitewash real problems in all sorts of different ways. And when we invoke these legal words, we can’t invoke them without the baggage. In the words of Inigo Montoya, you keep using that word; I don’t think it means what you think it means.

And the law is not neutral. The law is not some neutral force that we reach out to and we can pull into our terms of service or into our online spaces without bringing with it its long, long history of oppressing the oppressed. The law is both something that shapes the world, for example we know what reputational harm looks like because it is defamatory. And it’s shaped by it. We know what defamation is because we know what reputational harm looks like.

And so when we talk about these laws, they’re also contested sites. The question of whether material is defamatory, the questions of whether these laws apply at all is also a thing that we need to do some serious reckoning with. So, although these talismans may appear to be ready-to-wear, perfect with every outfit, their invocation suggests a bright-line rule that, in practice, it’s really messy. Both in the law and in its enforcement. And the power of the words is what makes them dangerous. The fact that they feel neutral is what means that we should give them a second look.

So, I want to turn back to our headlines from earlier. Has anybody seen the movie They Live? Okay, at least one person. Well then, this joke is worth it. So, in They Live, which is a cult movie that I’m not sure everyone should go see but everyone should go watch this clip. John Carpenter, the lead character, puts on these sunglasses which allow him to discover, and I quote Wikipedia, “the ruling class are in fact aliens concealing their appearance and manipulating people to spend money, breed, and accept the status quo with subliminal messages in mass media.” So, I’m going to ask us to put on our They Live glasses and turn back to these headlines.

So, “Apple to FBI: Forcing us to Unlock iPhone Suddenly Politicizes Engineering Decisions That We Framed as Technical.” “Cloudflare and How our Business Model is Protected by a Non-Interventionist Position.” “Verizon: net neutrality violates our vision of how to make money.” To be fair, that’s actually pretty obvious from the face of the rest of the argument. And “Twitter’s Tony Wang: ‘We have no clue what constitutes appropriate content on our platform, nor should we have to decide. Because Because that’s hard and would piss people off.”

And I both mean these as jokes and not as jokes at all, because I sympathize deeply. And I actually share the positions of many of the people I’m making fun of. But I understand that for a company like Cloudflare, or a company like Apple, the free speech argument may be what they have. They’re using the tools that they have in order to make the argument that they feel is actually just normatively for the best outcome.

But once we understand that legal talismans are protective invocations, we have to be critical of them. Even the ones we like. Because they come from this history of using these terms in ways that actually don’t create— The shorthand is not comprehensible to users. And the shorthand is not comprehensible to people more generally.

So, when legal talismans import difficult concepts, we see the distributional effects of offloading legal responsibility. We see that there are real consequences to Twitter, who has lawyers, to push off decisions about what constitutes defamatory to people who use Twitter. Who generally don’t have lawyers. And that legal talismans can both be overbroad and yet too narrow. There are lots of things— I don’t feel like I have to say this too much, but there are lots of things that are perfectly legal that are still harmful. And that’s something that comes up in the online abuse space a lot. And indeed, framing abuse around what’s legally permissible and impermissible is deeply ill-advised.

The insertion of legal language creates the idea that law, not ethics or empathy, is what governs. And it substitutes for real discussions of the values that define community spaces. I’m not saying that you can’t come to the exact same conclusion about what is appropriate on your platform or what you should do that you would if you invoked the idea of free speech. But I’m saying that the shorthand of saying, “Well, we’re making all the same arguments they made in all of the free free speech cases that most people haven’t read,” is not comprehensible to users. And nor is things like the real questions that I feel like we should ask, like what legal structures does this policy invoke? And what values do those legal structures take for granted? When we talk about defamation, it’s pretty much impossible to separate defamation historically from fear of sex workers. Is that what you meant? Is that the value that you want your legal structure to take? And whose interest do those legal structures serve?

And again, we may come to the same answers. But just going through this process of understanding our own normative values in a context that’s other than legal argumentation allows us to ask why? And why is harder. Why no defamation? Why free speech? Why these processes? Why these distributional outcomes?

And it’s much harder than this. Because the talismans are so pretty, right? They’re shiny and they’re distracting and we get caught up in whether they’re the right talisman or whether there’s some ugly thing on them. They’re really deeply appealing. But if we want our online spaces to avoid replicating the mistakes that our legal system has already made, we have to move past them. Thank you.

Kendra Albert: So, I was asked to end with a question, because this is meant to provoke a discussion and I have all the faith that this will provoke a discussion independent of whether I ended with a question or not. But I do have a question, the one that I’m really struggling with now, having spent a lot of time thinking about the baggage of legal systems, which is: Are the alternatives worse? And so, thank you so much for your time and attention. And I think I’m going to call on people and then someone will come around with a microphone. So are there questions, or if you’re going to do a comment, tweet-length, please. Otherwise other folks won’t necessarily get to speak.

[No one volunteers]

Well, I guess I’ve convinced everybody.

Audience 1: I hope you don’t take this the wrong way, but do you want to address the fact that most people don’t even read this information to begin with? And—

Albert: Sure, I’d be happy to. I mean, I think it reinforces my point about offloading consequences onto users, right. The sort of fiction that the terms are binding whether you’ve read them or not is really convenient from a sort of contractual business perspective. Because if businesses or companies or people had to make sure someone understands the contract before it was binding, it’d be a lot harder for courts, right, because that’s a deeply factual question. And it would be a lot harder for us to make the kinds of contractual transactions that many argue are what make capitalist systems work.

So I think it just reinforces my point, that people don’t read this stuff. Because it doesn’t not bind them because they don’t read them, and it just offloads responsibility for— Like, the enforcement can happen independent of whether you knew the thing or not.

Audience 2: So, following up on that, if enforcement is let’s say independent of whether the user is really cognizant of what’s in the TOS, then does it matter that the TOS is speaking in legal terms instead of in terms that the user might be more familiar with? And the other point I kind of wanted to bring in was that I think it’s easy for non-lawyers to think of of lawyering as kind of rarified and obscure. And so I wonder if you can talk about the value of including the broader community in the normative discussion that necessarily underlies all of those legal concepts.

Albert: Yes. Sorry, I’m going to address the second part first and then talk about the TOS. I think that obviously there’s some irony to giving this talk as a layer, because my value proposition is like, “Hey! I know these words. You should hire me.” But I do think that really good lawyering is not around legal terms. And I think good terms of service don’t just use these legal terms. Sometimes you kind of can’t get away with not, because actually you can need all the baggage. There is no other set of words that sort of comes out to mean the same thing.

But I think that community involvement is, as you said, really important because that can help people figure out what the pain points are in terms of people not understanding what their obligations are. I was trying to think of some other examples, just in case somebody quizzed me, before this. And one of the things that I kept coming back to is the sort of “no copyright infringement intended” that you see kind of often in fandom. Which is sort of totally talismanic, and it’s like, “Please don’t sue me. I didn’t mean it.” Which unfortunately doesn’t really matter a ton for many copyright infringement lawsuits.

But yeah, so I think when you see that kind of community output, where people are clearly trying to engage on the legal substance or trying to come up with a better way to explain what they mean, that’s a place where lawyering can be really helpful in translating what the community wants into words that are cognizable to the legal system, because that’s kind of what lawyering’s about.

In terms of the terms of service and enforcement… So, I admit I actually originally did structure this talk around things in the terms of service. But then I sort of figured I would make it a little more broad because terms of service are in some ways actual legal documents. They’re contracts, right, and although they’re not usually enforced by the courts, they are usually written as enforceable.

So I think what actually worries me more is the presence of these words in spaces where like, not even terms of service. Like in Yik Yak, it’s in the content guidelines, which are incorporated by reference into the terms of service but are sort of meant to be the cognizable easily-understandable like, you can follow these things.

And I’m sorry. I’m not sure I answered your question correctly. I maybe talked around it for a while. But if you want to re-ask it I will try my best to answer it directly. Or I can just move on.

Audience 3: So, speaking of users not reading terms of service, let’s say that you read it but you disagree with it. Right now there’s not currently a mechanism where you can say, “Actually I don’t agree to this part.” So it’s like, “Okay, well then you don’t like our terms of service at Slack? Then don’t use Slack.” And as somebody who’s not involved in the company or not a lawyer, what recourse do I have? Is that something that companies are interested? How would I as an engaged community member go about making some kind of change?

Albert: So, the sort of legal answer is don’t use the service. The sort of actual answer is I do think there are some companies and some groups who actually really care deeply what their users think about their terms of service, and are responsive to user feedback. I’ve been in conversations where folks were like, “Well, somebody really said they’re not joining our service because of our arbitration clause. Can we get rid of out arbitration clause?” That is an actual conversation that I’ve seen happen, so it’s not just a figment of my imagination. (Although sometimes it feels like it was.)

But users do have the recourse of reaching out and being like, “Hey, I don’t like this thing that you’re doing.” Realistically, part of the problem is all of the stuff we talked about with respect to defamation, some of that same stuff holds true in contract law. Like the history of contracts of adhesion, which is contracts that are non-negotiable. And sort of the way that that’s come to govern in terms of service is kind of…in some ways not particularly reconcilable with a model that emphasizes user agency. Like, you could try to send them back versions of their terms of service with parts crossed out. Good luck. But our body of contract law either is not well-equipped if you think the goal should be agency by third parties, or is very well-equipped if you think the goal should be having companies bind people as easily as possible to contracts.

So, unfortunately there aren’t a ton of answers, but I do think you can, especially if you know the company is one that maybe cares about users, or think the company is one that cares about users, reaching out to them and being like, “Hey, I really want to use your service but you have this thing like…you know. Sorry.”

Audience 4: So, this is a half-baked idea, so I may regret bringing it up. I’m wondering if your critique of legal talismans could be extended to the way that courts themselves apply legal terms to conclusions. And I’m thinking of the way that the Supreme Court will decide what is obscenity or not, what conduct is speech or not. Is that also a cultural perspective that is having a label slapped on it at the end, sort of concealing what’s really going on?

Albert: Yeah, the secret problem with this argument is it applies to all law. I mean, or it’s not a problem at all with this argument, that putting things into categories that are complicated, that people don’t understand, and then applying arbitrary rules to them is kind of what judges do and what lawyers do all the time? That this problem is not unique to online platforms. And so, some people would consider that a flaw in my argument, but I consider it a strength.

And what I mean by that is that yes, it turns out like, all of these systems have this baggage and have these roots that if we dig deep enough we’re gong to find the creepy crawlies that—this metaphor got away from me—that are under the law, right? That the baggage is not unique to one area of law. And I think often, actually, when we talk about the Internet, we all can come to it from this perspective that everything is new and nothing has happened before.

And I think that the argument here is that we should take the lessons that we’ve learned from all of this other stuff about how you know, we don’t like it when judges misunderstand technology and then come to the wrong decisions. Well, it turns out judges have been misunderstanding things since time immemorial. And the the problems are not unique to technology, but we can learn a lot from the scholarship that has already criticized these phenomenons, and that’s part of why I invoked Duncan Kennedy.

Audience 5: Seems like to avoid falling into the trap you describe if I was to write a set a set of terms of service are just guidelines for something I run, I would have to avoid any reference to any legal terminology whatsoever. I can’t say “harassment.” I can’t say “libel.” I can’t say “defamation.” Even if I go to really like, fourth-grade plain English, it seems like I can’t really avoid these terms, so what do I do?

Albert: I mean, I do think you can avoid these terms. I actually think since I’d started thinking about this, I actually think Twitter and Facebook have made huge progress on their content guidelines about removing legal terms. And part of that is because I think they realized that the legal terms were not actually serving a good purpose for what they wanted to accomplish. But if you look at Facebook’s conduct guidelines, Facebook’s conduct guidelines do not contain the word “defame.” Their terms of service might, but their content content guidelines don’t.

Audience 5: [inaudible]

Albert: The word “defame.” They don’t talk about defamation.

Audience 5: Does it say “harassment,” because that also has a lot of legal…

Albert: Yeah, but harassment… You usually need a word in front of harassment before you get a very specific set of legal technical terms in a way that’s different than defamation or libel or slander.

So I do think it’s possible to move away from those. And I actually think that for— Speaking of half-baked ideas. Forcing people to write their terms of service in “explain it to me like I’m five” style might actually not be a bad idea for forcing people to actually reckon with what they’re putting in there. Because the reality is that people often are doing this in such a way that they’re not spending a ton of time— That as Jonathan suggested it’s sort of the fruitcake, right. It’s like you know, they grabbed it, they copied it from some other site, modified the parts that obviously should be modified and then turned it over. And I know none of the lawyers in this room would ever do that. But I’ve I’ve heard that it happens.

And so I think that the process of actually having to sit down and think about what you mean is like, really important. And being intentional about the process by which you come up with the terms that govern your community and the behavior that’s acceptable in your community, forces your instincts into tension with the sort of realistic focus of what you’re doing. So I do think it’s actually possible. It may be hard, but so are a lot of things that are worth doing.

Audience 6: Thank you. This was a great talk. I find it really fascinating that I didn’t really know anything about the…basically the more problematic meanings of phrases like defamation and other types of things you brought up. And so applying critical legal studies must be a really key part of this argument, and realizing that little talismans are an issue.

So I’m wondering how you bridge the gap between people kind of glibly or not glibly using legal terms casually, whether or not it’s in news reports, or in terms of service, or in other capacities online, and getting to the part where you actually start to see that it’s problematic not just in a legal sense and the fact that laws are complicated, legal terms are complicated, but they also have even more underlying issues beyond that.

Albert: Yeah, I think there are some folks who write like… It’s hard because I think most critical legal scholarship would not necessarily characterize itself in the terms I have characterized. The sort of defamiliarize the familiar, or with the express purpose of complicating these terms. Although I think that that is one of the very powerful things it brings to the table, is the sort of historical understanding of where these words come from. And it’s actually something I think that people should learn more in law school. Thank you, Jon Hansen.

So I do think law school is actually one really good place for people to learn the history of these terms. And it’s sort of something that doesn’t really happen in the traditional doctrinal subjects, where everyone’s so worried about making sure that you understand what strict scrutiny is (which is a First Amendment test) that they forget to talk about why we have incitement law, or what defamation means. In fact I’m pretty sure my First Amendment course did not cover defamation very much at all.

So I think it is possible to write persuasively for the public on this. It’s definitely hard, because they can often seem like this historical perspective is really like, “Oh, well that was the past and things are better now,” right. When we’re talking about the history defamation, “Oh, in 2014 they got rid of that part about women’s chastity. And like 2012, homosexuality is no longer per se libelous, hurray!” So it can seem sort of historical, but I think—to be trite—those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it. Like that we think of these new terms and we come up with these new legal concepts, and we make the same mistakes that we often had made before.

So I think you can write publicly on the subject, and I think just literally reading a law review article in then writing a blog post about being like, “Wow, I found out all these things about defamation.” Or, “Wow, it turns out the history of incitement is full of a lot of people wanting to kill communists,” is a useful contribution to unpacking some of these things.

Audience 7: Hi. Thanks. So, this was super interesting. I work a lot with critical legal studies, and I have a question regarding the content that legal concepts carry. Which is sort of what you’re unpacking and critics unpack. And sort of like the more generalized content that people have about those talismans and how they use them to communicate and achieve things in their daily lives, which doesn’t necessarily match the unpacked content which you’re doing.

And I wonder how you see the interaction of this unpacked content, which usually comes from the past and this constant construction of concepts that happens in daily life that doesn’t really have to be related and that actually leads to many legal outcomes that strategically people in the headlines that you showed… I don’t know, Apple or Twitter used. And how you see how they relate and how to…I don’t know..

Albert: It’s a great question. And I think one thing to be really careful of is to not talk about the legal definition as the right one? Like, I think especially lawyers have this idea that we have found the one true meaning of this term and it comes from this history, and I apologize if that’s what I was sort of suggesting. Because that is one true meaning of the term, but it is not the one true meaning of the term to sort of rule them all, right?

Cultural understandings of defamation actually carry huge amounts of weight in how we understand how these things work. We can’t just ignore them because we like the legal one better. And this happens straight up constantly in discussions of free speech. Because people who talk about free speech are often using it as a shorthand for, “I feel like my voice isn’t being heard,” or, “I’m being denied due process by Twitter,” or whatever. And whether you agree with them actually or not, the sort of facile, “Well, the government’s not here so what are you complaining about?” I think is just not necessarily constructive as a response.

So I think it’s really important to think about popular definitions and legal definitions as both valid for different things. And that the legal definition is probably going to win in court, right? That the virtue of it is that courts apply legal definitions, and knowledge of those legal definitions can be used very effectively as a source of authority in ways that can sort of silence more popular cultural constructions. That’s the “no copyright infringement intended” thing, which is sort of a tag that people put on fan works like fanfiction, where they’re using other people’s copyrighted characters that may or may not be copyrighted, in ways that may or may not be Fair Use.

It is tempting as a lawyer to be like, “Hey, I don’t have to pay attention to that because that’s not real copyright.” But cultural constructions matter. And how people think about the law matters, in some cases more than what the law is… I think it’s Jessica Silbey who’s been doing a lot of work on what people mean when they talk about copyright, and what creators mean when they talk about copyright. And I think that sort of more ethnographic work is a really powerful way to look at cultural consensus around what legal terms mean in a way that, because of the constructions of academic knowledge, gives it authority that’s maybe comparable to legal authority.

So to sort of sum up a sort of rambling answer, it’s just really important not to talk about one term as correct, because one term might be enforceable within the law, and that the cultural understandings of these terms are in many ways more impactful on on people’s daily life than the sort of reality of what what may be on the books.

Audience 8: Hi, thanks for that. I got a lot of thoughts going through my head because I actually spent the morning looking at the community standards of three of the biggest social media platforms and said, “Wow, awesome. [inaudible] for me.” And one of the things that actually I wanted to draw out is what you began with by talking about the companies aren’t providing us with a positive right.

And one of the things that actually stood out for me is when you look at their community guidelines, or the Twitter rules, they really invoke all this very flowery language about, “We’re providing you with the opportunity to share and exchange in this bounty of goodness.” And it seems like they would argue, right, that that is a positive right, just the ability to be able to go forth and prosper. And we can roll our eyes and we know it’s a bit ridiculous, but I’m wondering if that has any kind of standing in terms of how that makes us think about this notion of rights. And if that has any kind of legal framing in that question.

Albert: So, one of the things law school talks a lot about it is there’s no right without a remedy. This idea that without some sort of consequence for the violation of a right, that the right might as well not exist. And so although often… Obviously having just read them, you’re totally correct. There’s all this kind of flowery language about “using our information service to spread you global peace and flowers and chocolate worldwide, and like pets and kittens” or whatever. The reality—and this is sort of where the cultural construction versus legal reality kind of butt heads—is that if you look at the terms and not the community guidelines, what they’re going to say is that “we can terminate your service at any time” and like, “if we do, your remedy is we’ll give you the money we might owe you back.” Which in the context of a free service is like, “Okay, great. So I get nothing.”

So, without remedies positive rights are not necessarily meaningful. And this is something that comes up in all kinds of different forms of jurisprudence. But if we talk about these documents as sort of trying to give people a sense of foundational rights, then the question is actually like, do they provide due process or things that we could attempt to understand as due process rights? Or like, do they provide remedies for not being able to access the service anymore? And I’m going to pretty much that’s that the answer is probably no. So in the absence of a remedy, what is a right?.

Audience 9: Thanks, Kendra, so much for a lot of this. Certainly, your last question got me thinking a little bit about the alternatives. And it kinda led me to a place which I guess is going to be a question for you, and that’s really how much is the role of the terms of service to sort of set community values and standards, and communicate “this is what we do here” and give notice, versus how much is simply, “Oh, this is a shield in case Angry Person wants to litigate against us because we arbitrarily booted him off,” or her, they. And kind of what rule…like, should there be two separate things, or something like that?

Albert:

Yeah. I think it’s a great question, and I think actually many platforms have sort of gone to two separate things which I’ve been maybe alluding to somewhat, community guidelines versus terms of service rate, and how those differ. I mean, I think terms of service are fundamentally legal documents, and they’re often drafted— Not always, certainly not always, and I don’t mean to impugn the good names of many of the lawyers who draft up terms of service, of which I am one. So, they are often drafted with an eye toward shielding from liability, and not with the sort of foundational document in mind.

And I think that the… I have not seen, although I welcome suggestions on where to look, people who have done the sort of foundational document thing in a way that passed the sniff test. Like Facebook’s sort attempt at like, global governance where like, 1% of all Facebook users would have to vote on something. Which is just an enormous amount of people that was unrealistic in every way to think that they would engage with the issues Facebook was pushing.

So I do think yeah, there’s sort of this idea of splitting them off, and these have two separate audiences, and this is our legally binding one. But I mean, if your community guidelines are all puppies and rainbows, and your your legally binding document is all like, “we reserve the right to terminate at any time, we can kick you you off for any reason,” I think you may be trying to say one thing out of one side of your mouth and another thing out of the other side of your mouth. And in maybe some contexts that’s totally appropriate and totally okay. But you have to question whether that represents the values that you want to try to promote through the intentional process of actually thinking about “what is it we’re trying to do here?”

And that there are costs to being intentional and thinking about values. Like yes, not having an arbitration clause in your contract may cost you a lot more money because you’re going to get sued by a bunch of plaintiffs’ lawyers for a class action. But if you think arbitration clauses are bad, then that’s maybe a decision you make. All of these decisions involve tradeoffs.

So I think that individual companies do need to reckon with the reality that we’ve constructed. And why I ask if the alternatives are worse is that in some sense it’s like, “Well, am I now asking companies to do the kind of soul-searching that our democratically-elected government has failed at?” And I am. And I realize that that’s a pretty hard position for me to take on a lot of days, and in a lot of places. Because I don’t necessarily trust companies that at the moment— They’re making value statements anyway, right. Whether I like it or not. And I’d rather they were more intentional about their values. So I’m answering my own “Are the alternatives worse?” question.

I think we may be at time. So, seeing no people with their hands strenuously up, I want to thank you all so much for coming. And I’m happy to talk to folks after.