When I thought about this talk, I thought it would kinda be straight down the line, suggesting models, tactics for lifestyle hacking or what a new nomadism might look like. But sketching the talk out last night, I decided that I’d actually personalize this and talk about where I’ve come from, the things that I’ve done, and the effect that they’ve had on my thinking. But just to summarize briefly, reflecting back on everything that I’ve built recently. It can kind of be summarized as “the infrastructure by which I (and others) wish to live doesn’t exist; so we’ve no choice but to build it ourselves.” I kind of describe this and a lot of the other things I do at this present moment as being the soft end of stacktivism, which is another Big Picture Day that was hosted recently.

I spent five years of my life living in a computer game called Ultima Online. I’m not going to talk about that too much, but I did just want to punctuate the three things that I learned from living in that world. One was how to establish meaning when you’re not bound to a grand narrative, without a beginning, middle, or end; the basics of how economies function; and what community actually means.

When I was eighteen, I reread Siddhartha, and on a whim thought I would throw away all my possessions except for my laptop. I then also backed up all of my data onto a server, just in case I did lose the laptop. Around about the same time, I was putting together my degree show at art school, which was a kind of enormous building. I won’t actually talk about the specifics of it because it’s kind of weird. But I sunk £5000 into the project and destroyed all my clothes in the process. I was meant to be walking into a well-paid job when I left, doing data-mining for Sky. But that was at the point at which the financial industries collapsed, and to add insult to injury, around the same time as a result of a very messy family dispute around rent, etc. I got a counter-court judgement against my name and had all my bank accounts closed.

So at this point, I couldn’t rent property and I didn’t have a bank account. In many ways I felt like I didn’t exist, and it was kind of a prerehearsal for the [graduate?] of my future. But it was kind of okay because later in the year I moved into a mansion in Mayfair with some friends and opened a free school, the Temporary School of Thought. There’s probably too much to cover on the subject, but I think it’s important to point out the kind of key concepts and key experiences I had during that time. So I learned how to live in one of the most expensive cities in the world without money and have the best time of my life. I learned how to eat without an income. I learned how to live out of a single bag indefinitely. But probably most fundamentally, I got a really hard lesson in the infrastructure required to keep you alive.

Around the same time, we started a project called Nomadic Infrastructure, which was a rehash of a 70s book called Nomadic Furniture. This project never really came into fruition, but continues to live on probably in this event today, and also in my work on the unMonastery. The desire of that project (and it might be something that we might be able to map out today) is to create a bike-sized trailer that would allow you to move into derelict buildings and set up all the infrastructure that you needed within a couple of hours, including Internet.

So squatting is really great, but I started doing quite a lot of freelance web work and stuff, and cycling around at night when you need to find a new place to live kind of got a little bit tiring and difficult. I had this idea that maybe establishing a model or joining an existing model might be a better way to go. So around that time I moved into a LimaZulu Projects space, which is where I currently live with fourteen people, one shower. I often find the solidity of living in a fixed location quite difficult to deal with because it doesn’t really reflect the fluidity that I feel in my head. So for up to six months at a time, I often go nomadic again.

But what I’ve learned from my own experience of living at LimaZulu, but probably primarily those who move through the space and use the space, is that there’s no perfect model but that a low-cost self-made place such as LimaZulu can begin provide support structure for an alternative way of living. Kinda key to this understanding, and encountering other warehouse self-built spaces, is that actually the desire is not to build this perfect thing, but to actually create a multiplicity of space and the ability to move between them easily.

Some friends recently started a warehouse in which they collectivized all their clothes, and didn’t think that privacy was an important thing so put the bath in the kitchen. And the evolution of this project was it doesn’t make sense to build a micro-Utopia, let’s build small rooms throughout the house and rent it on AirBnB so other people can experience the way that we’re living. That’s I think an interesting project. I think it’s probably important to say in the context of London that the warehouse thing is kind of over, but two thirds of all office space in London is currently empty.

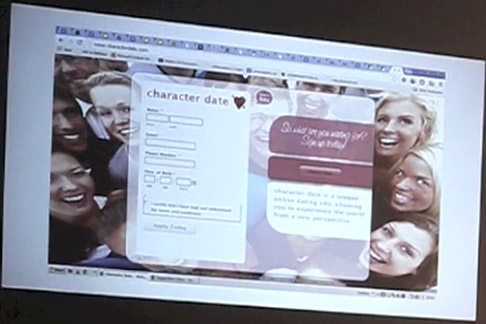

Fast-forward the time I was living at LimaZulu. About a year ago I started a project called Character Date with some other people. This was the most disastrous project I’ve ever had anything to do with, and no one should ever ever replicate anything that we did.

Fast-forward the time I was living at LimaZulu. About a year ago I started a project called Character Date with some other people. This was the most disastrous project I’ve ever had anything to do with, and no one should ever ever replicate anything that we did.

Audience member: And you were told this in advance.

Ben: And I was told this in advance. But the basic aim of Character Date was to construct a network of individuals with alternative identities for a self-built fiction to appropriate existing resources and establish power in real networks of influence. It kind of worked. It was kind of how I got my job at the Serpentine. But the key things that we learned I’d like to share, which is that when you try to create characters to exist in the world, you construct a really powerful toolset for building and reflecting on the social and physical infrastructure that maintains our place in the world. You also find out the material and social integrity for new ways of existing is exceptionally high, and that there exist an innumerable amount services that can be reorientated to completely new purposes. You also find out that creating a real company is actually kind of easy, running it with fictional characters is a bit more difficult, and that you shouldn’t try to break reality at scale with unstable human beings. I will never re-run this project.

So, that’s a collection of things. What I’ve been thinking about recently is how combined services might support an alternative way of living. And within that I’ve been asking the question if you combine say, a member’s club of a gym, a 24-hour storage space, and an office space as a hostel, could you dramatically reduce the cost of your living whilst improving your standard of living? I think that there’s a number of services that currently exist and an interesting economic situation in which if we were to opt out of the current setup and begin to build new forms of infrastructure, and reorientate things completely differently, that we might end up with a very interesting scenario. But we shouldn’t do it with fictional characters.

Where all of this stuff kind of culminates in the present moment is in my contribution to a project called the unMonastery. Since this is a ten-minute talk, I’m going to explain it in short. It is a hacker space that maintains a social contract with the local community that houses it. And it aims to solve three problems. Large numbers of unemployed graduates, a gross number of empty properties throughout Europe, and the crisis of state provision with the onset of austerity. It also tries to do this by asking what does monastic life look like in the 21st century, and how would a contemporary version of a monastery function?

I’m not going to expand on the model too much, because I’m more interested in actually what happens when you begin to create new institutions and new forms of infrastructure. What I’ve found is that you kind of end up asking question you definitely weren’t asking at the beginning. And some of the things that unMonastery has raised for me is how does time work when you don’t have to go to work? What jurisdictional models, drawing on the monastic idea of the rule and how can those things influence the current current state of play, and what would an autonomous zone look like drawing on rule? What does travel look like for zero carbon nomads that actually have places to move between?

So just to share some of the lessons I’ve learned.

- You need friends with houses and resources in order to survive these sorts of lifestyle, with a clear model of what your safety net is.

- The building process is still super messy at the moment. Without resources you’re going to have to work with what you’ve got and what the world throws at you.

- The opportunities offered in the present moment by several years of low-resource freedom and geographical fluidity is enormous compared to the existing mandated models of work.

- In order to move toward and build things that don’t require income and don’t generate capital, you need to have lived without these things and had the best time of your life, otherwise you definitely don’t know what you’re fighting for. This is clearly a privileged position.

- And finally precarity is definitely not cool.

That’s it.

Further Reference

The Temporary School site is offline, but Dougald Hine posted a collection of links to various notes and recordings of events, and media coverage, in 2009.