Golan Levin: Welcome back to our second presentation of the last session at Art && Code: Homemade: Digital Tools and Crafty Approaches. It’s my terrific pleasure to introduce Dr. Vernelle Noel, who is an architect, artist, and founding director of the Situated Computation and Design Lab at the University of Florida. Her research focuses on using design computation and ethnographic methods to investigate traditional and automated making, human-computer interaction, interdisciplinary creativity, and their intersections with society. Vernelle Noel.

Vernelle Noel: Hi. Thank you very much. Thank you Golan, thank you STUDIO for Creative Inquiry for having me. This weekend has been so good. I just wanna say I’ve been so inspired. I will be reaching out to some of you. I’m thoroughly this weekend, okay. I just want to say that. This has been great.

Okay. And so I’ll start to share with you my work or presentation or thoughts around art, code and gift-giving as we are all contained or working from home or trying to be creative from home. So I’m gonna share my screen now.

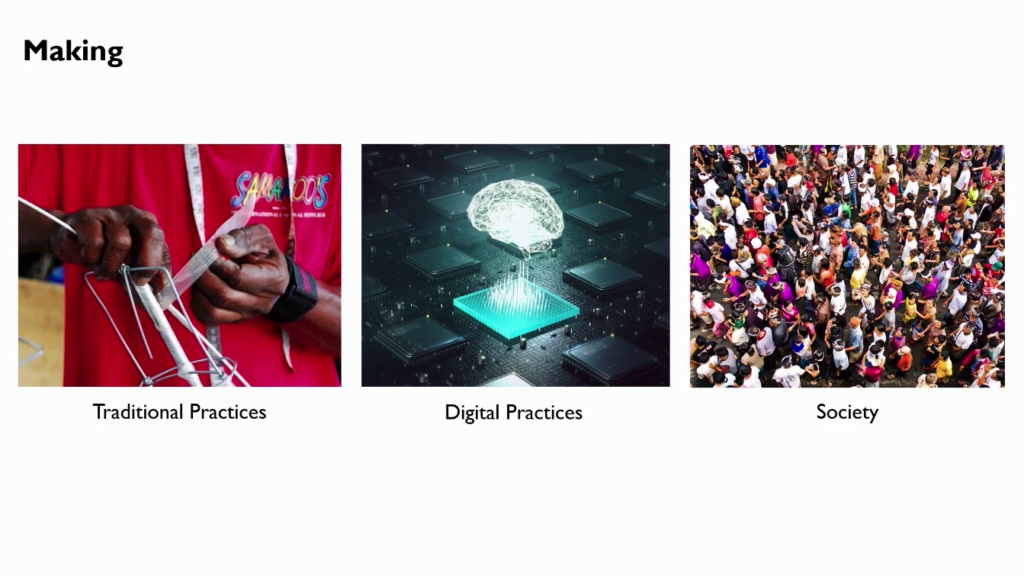

And just a little bit of introduction into my work or my scholarship. I look into making. And that’s traditional making practices, digital practices, and their intersections with society. So understanding what that relationship is, can be, or might be, and how they influence each other. So how making practices in society can influence the technologies that we develop, right. So I make tools, processes, technologies, etc., and really question culture, society, and design through them.

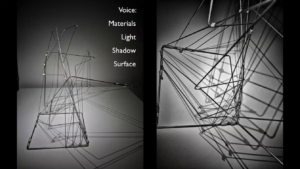

And With Golan’s prompt of this talk, I started thinking of my feeling, my love, why I love art so much and why I love everything I’ve been seeing so far. It’s because art is a voice, right. And I love art as a voice because as Cyril I think was mentioning earlier today, we have so many gatekeepers in other sort of professional space that art, we can have a voice in almost most anything that we have around us or available to us.

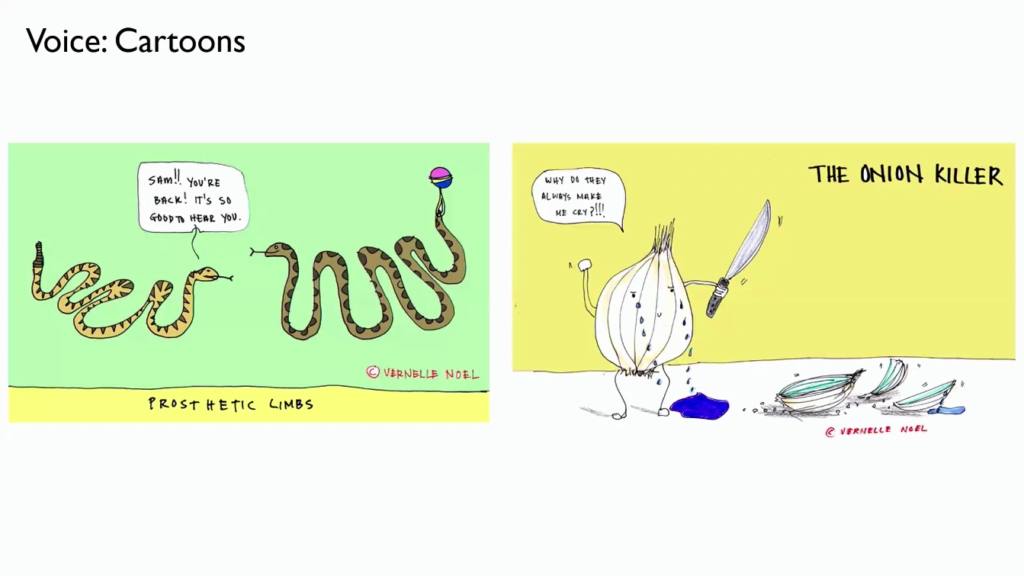

And so I play with many voices. I’ve needed many voices at different times in life. Sometimes I do cartoons, because things crack me up and I just find things weird and so at one point I had to do cartoons for that voice for myself.

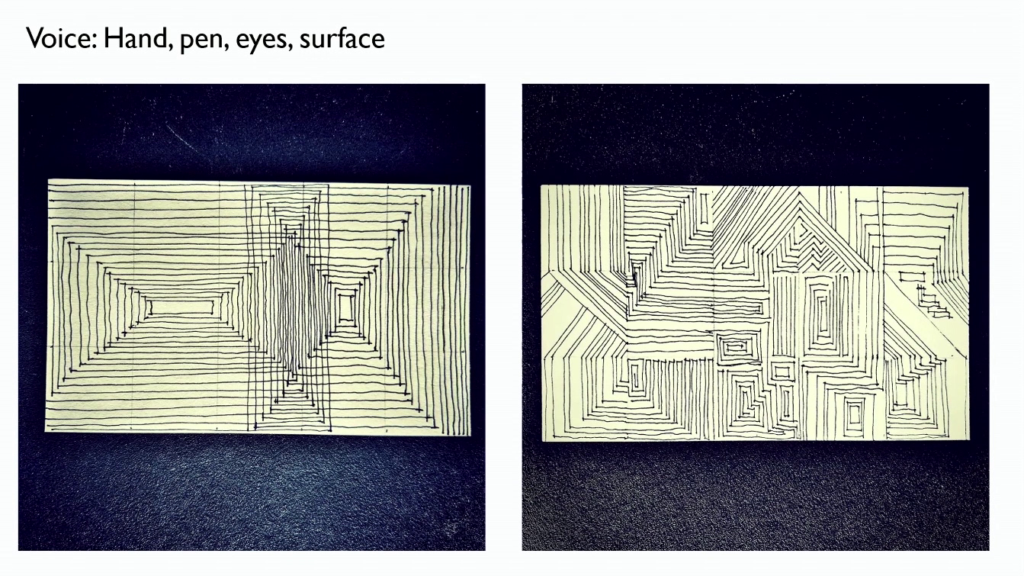

I like to draw. And a daily ritual I had of drawing lines on notecards, it was just something that I…I needed to draw, I needed an expression, I needed a voice sometimes every day to go through that ritual, and so these are examples of some of the things I used to do.

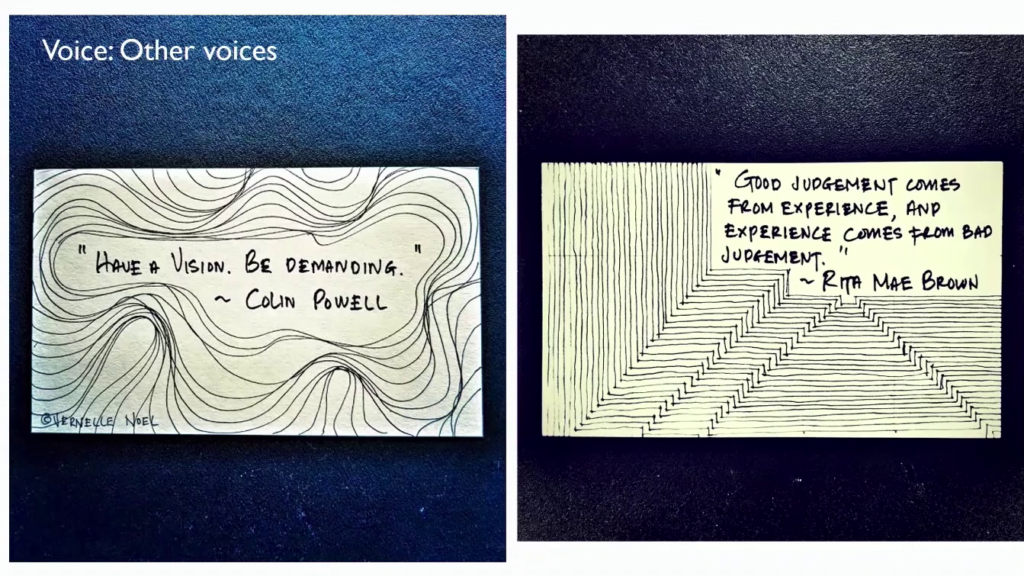

Then sometimes I need a voice that’s talking to me or that I want to think about for a while. So sometimes on these notecards and sketches I would include quotes or things that I’m thinking about that I might want to share with others.

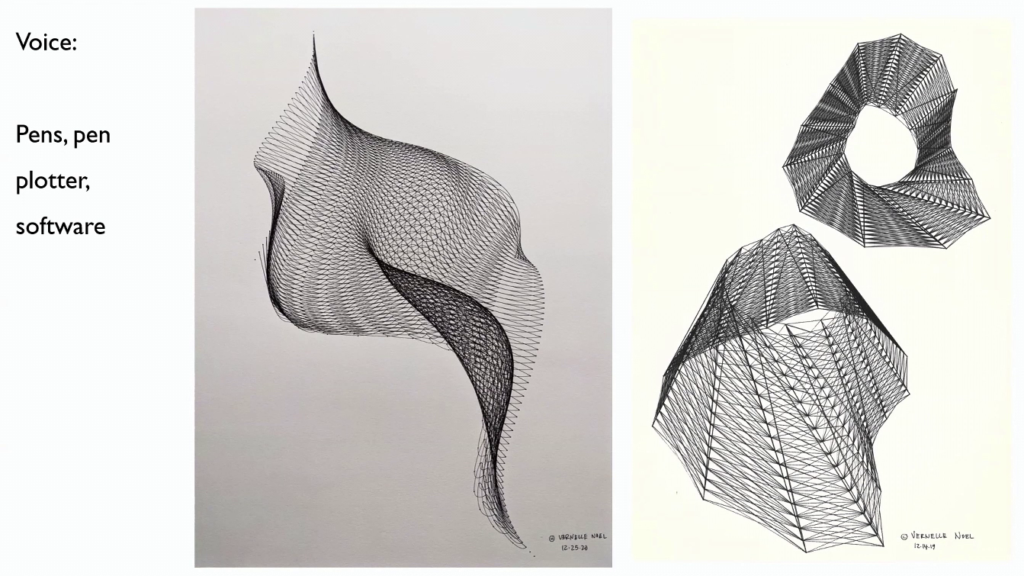

I’m continuing to explore drawing using pen plotters, software… Again it’s a voice. I want to share or show something that I’m trying or exploring.

Another voice being crafts and textiles. This is an artifact, an installation I made in my graduate studies with Leah Buechley, actually. You’ve heard her name a lot during this festival. But when she was my teacher this is something I made in her class, one of our projects where I explored yarn, liquid cement, and exploring sort of what we can get structurally and aesthetically using weaving—yarn—using digital fabrication.

E‑textiles. Electronics in textiles, that was another voice.

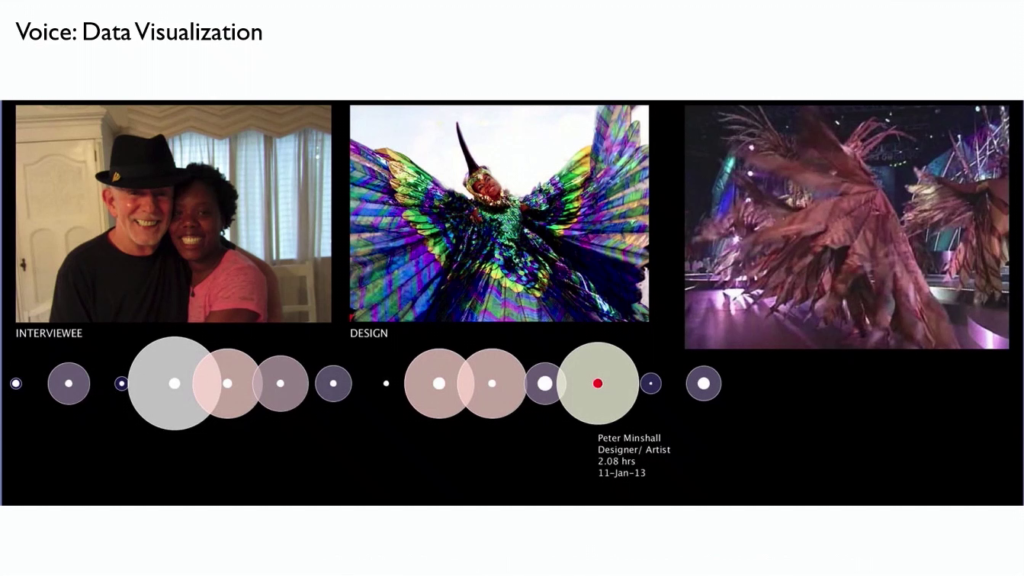

The visualizing of data. That doesn’t come up much. So this was me exploring data based on my field work and research in Carnival in Trinidad, which I’ll get back to in a bit.

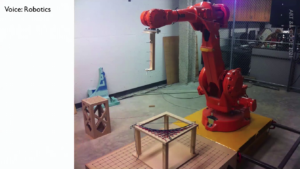

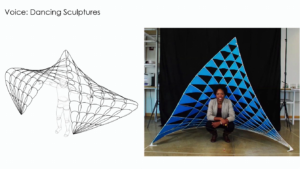

I work on robotics, dancing sculptures.

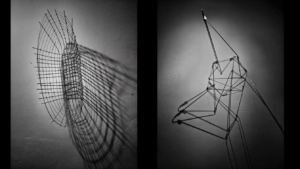

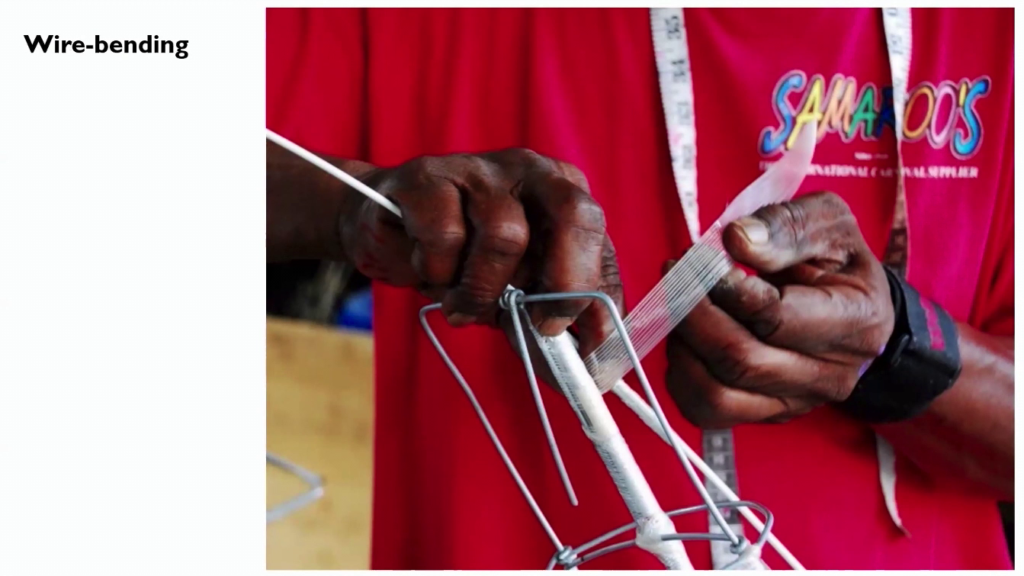

But today what I’ll be sharing with everyone is my work in wire-bending, right. And this is wire-bending that’s specific to Carnival in Trinidad and Tobago, but called the Trinidad Carnival.

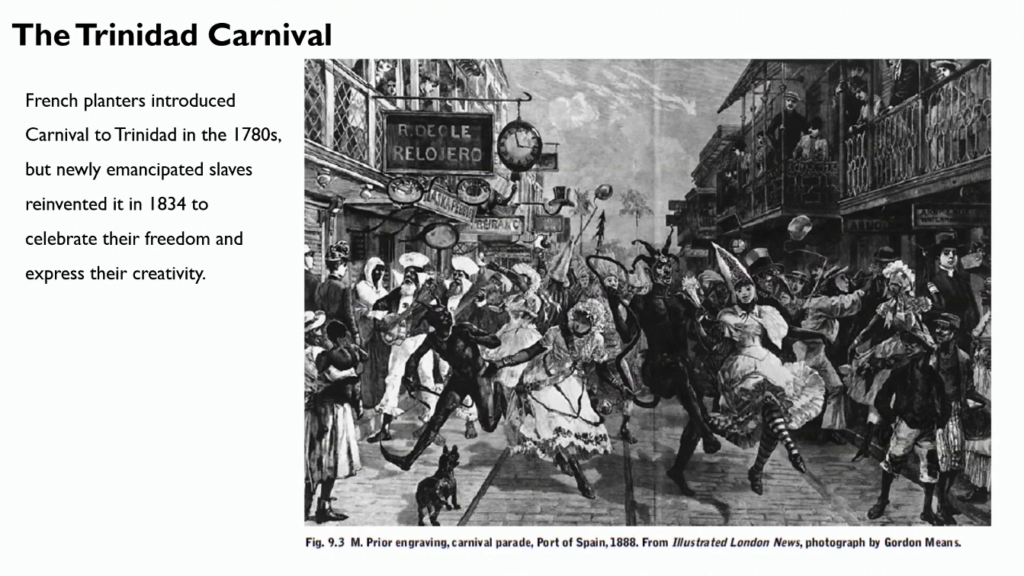

So a bit of an introduction. The Carnival was introduced in the 1780s to Trinidad. But emancipated slaves after the abolition of slavery used Carnival to celebrate their freedom. So from 1834. This is an engraving from 1888, where they reinvented the carnival to celebrate their freedom, show their aesthetic sensibility, create, make, etc.

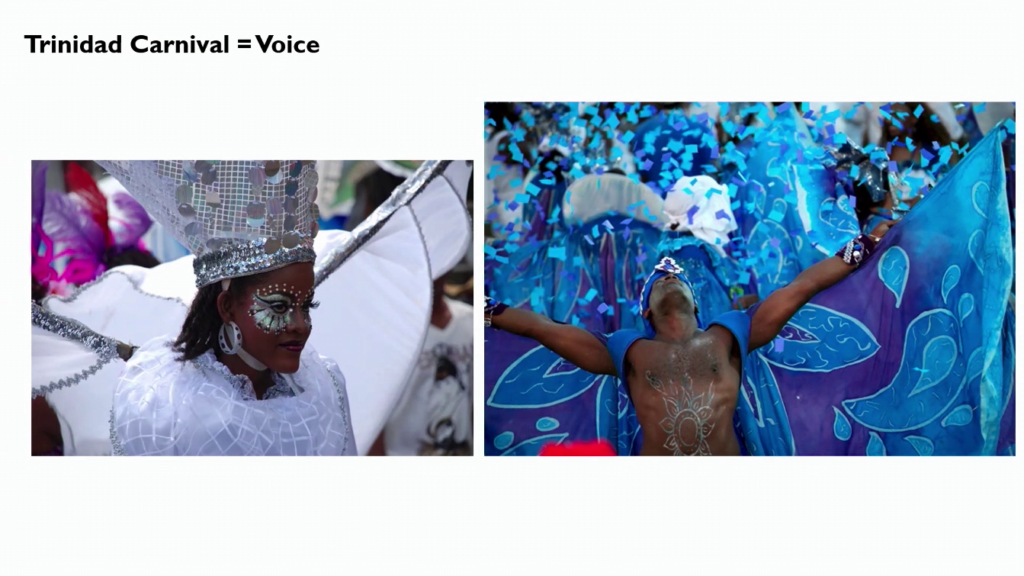

And Carnival is a voice, right. It’s a space, it’s a place where people express joy, release frustration, creativity, and more. So thinking of Carnival as a voice here, just like art, right.

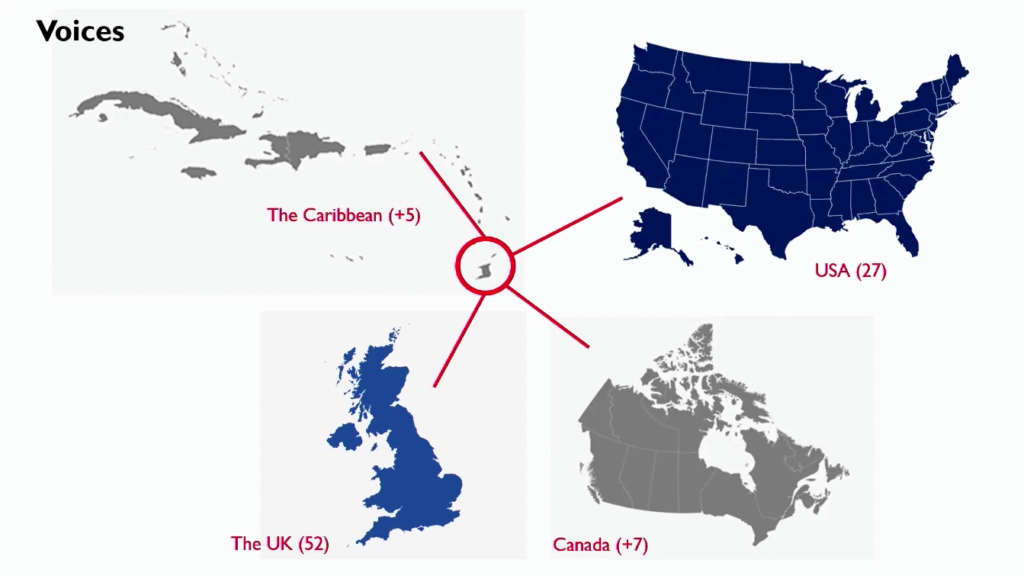

And these voices have been spread to other parts of the world. So there are several Trinidad Carnivals around the world. They have several in the US, the Caribbean, the UK, and Canada. So thinking of these voices that have spread, sharing these histories, these cultures, throughout the world.

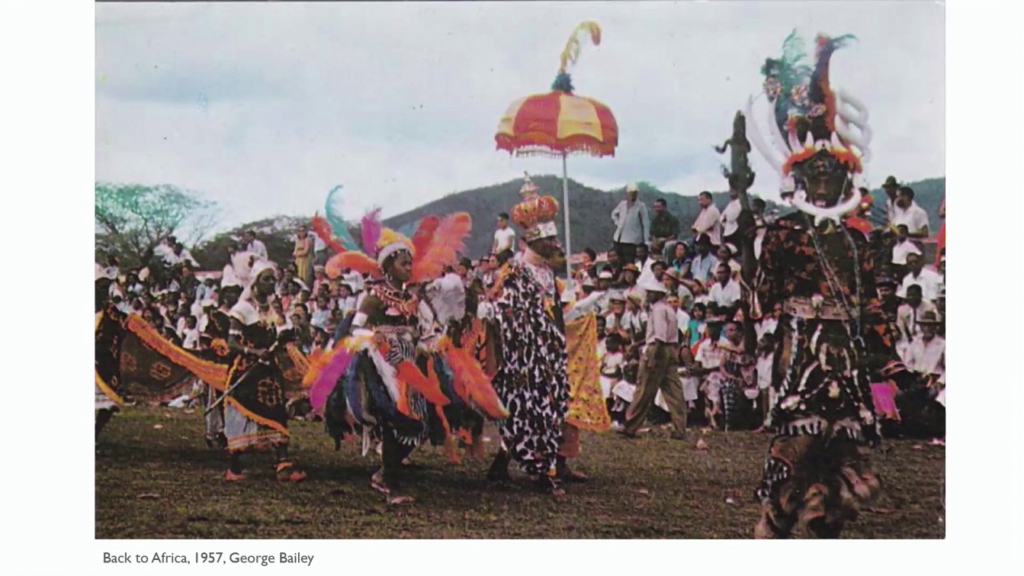

So I think of Carnival as the Internet of the time in that it was a space of public education, public participation, and public art. Here is a band from 1957 by George Bailey. The title of it was “Back to Africa.” This was based on research. They were [indistinct] research on costuming, people, what he saw or envisioned as what was happening in Africa, and his portrayal of the people and the costuming that would be happening, telling us these lessons, these histories, commenting on social and political issues. So Carnival is a very public space of education and art.

So communities and people come together, making artifacts for the carnival. There are kiddies.

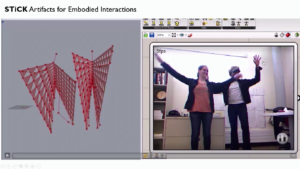

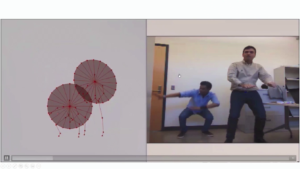

And in part of my work, I have explored how we might engage digitally with Carnival. And so this was an experimental I did several years ago playing with how we might interact with what I call stick artifacts. So artifacts that are spatial, temporal—meaning lasting only but for a while, corporeal, and kinetic. And this is another example of exploring how people might interact with digital artifacts coming out of Carnival.

And so when it comes to the craft of wire-bending, wire-bending started around the 1930s. And it’s the most highly-developed craft coming out of Carnival. So, dancing sculptures and costuming such as what you’re seeing here. And costumes are made based on those technical principles. And in my research started in 2012/2013, that’s when I found that this craft was dying. So thinking of this craft as something bad has history and culture embedded in it, its disappearance means that these voices are disappearing, right. So this language is disappearing, these voices that speak through this language, they’re dying, the voice is dying. So these histories of rebellion and resistance against oppression, slavery, freedom, joy, etc., opportunities for these voices are technically disappearing, if this craft is disappearing

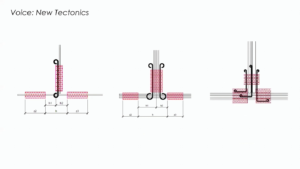

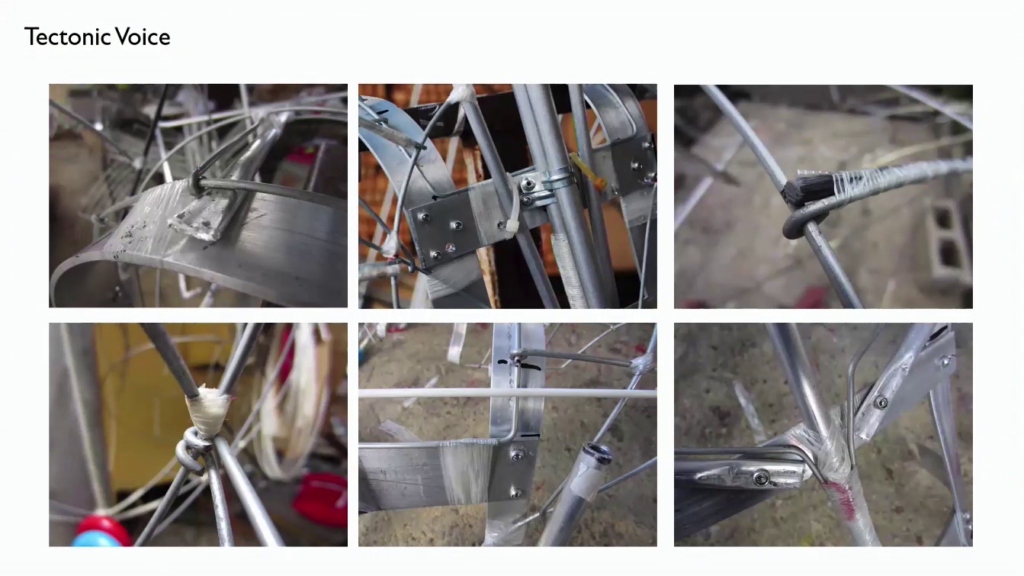

And so these are images of the tectonic voice of the practice. Just showing you here where aluminum rods, fiberglass rods, galvanized wire, aluminum flats, etc., and use of adhesive tapes.

And so my desire, I guess, was to revive and reconfigure this dying voice. So I want to share with you my process for how I’m attempting to do this through and in my work.

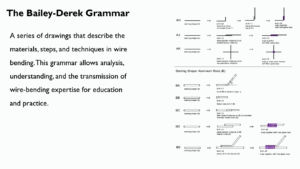

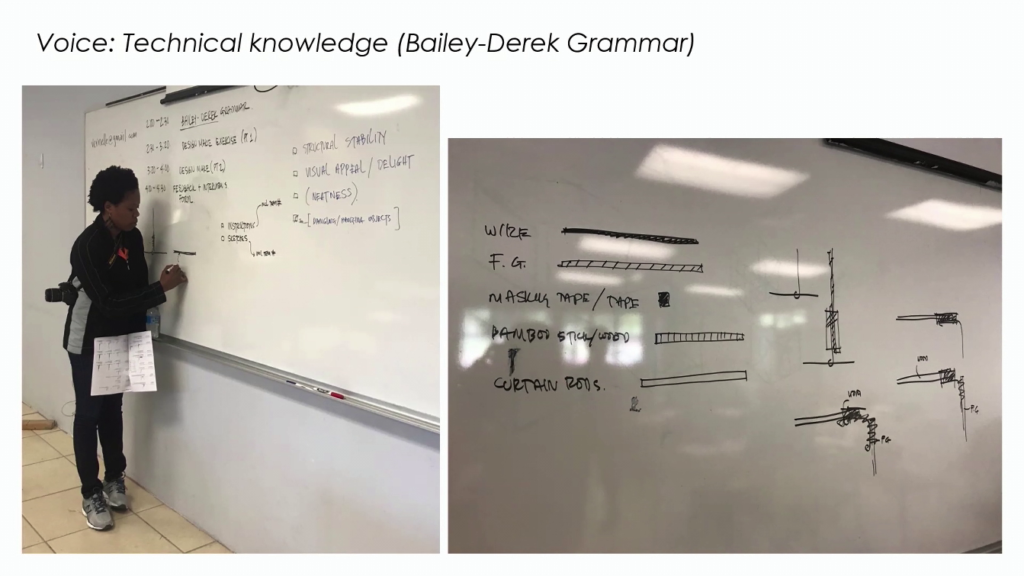

So I started by going on site, going to Trinidad—I’m from Trinidad—and studying the work of Albert Bailey and Stephen Derek, interviewing them, looking at their artifacts, etc. And then, from my continued examination of them and their work, study of their work, I developed the Bailey-Derek Grammar, which I named after them. And what this grammar does is it describes wire-bending using steps and rules so that this knowledge and this craft can be shared with others. Because currently there is no pedagogy to pass this craft on. So this also highlights a kind of computational algorithmic way, codified way, of learning and engaging in this process. So its purpose is to allow analysis of the craft, synthesis for design, and transmission of this knowledge for both practice and education.

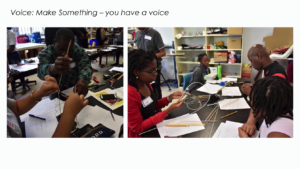

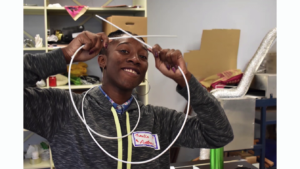

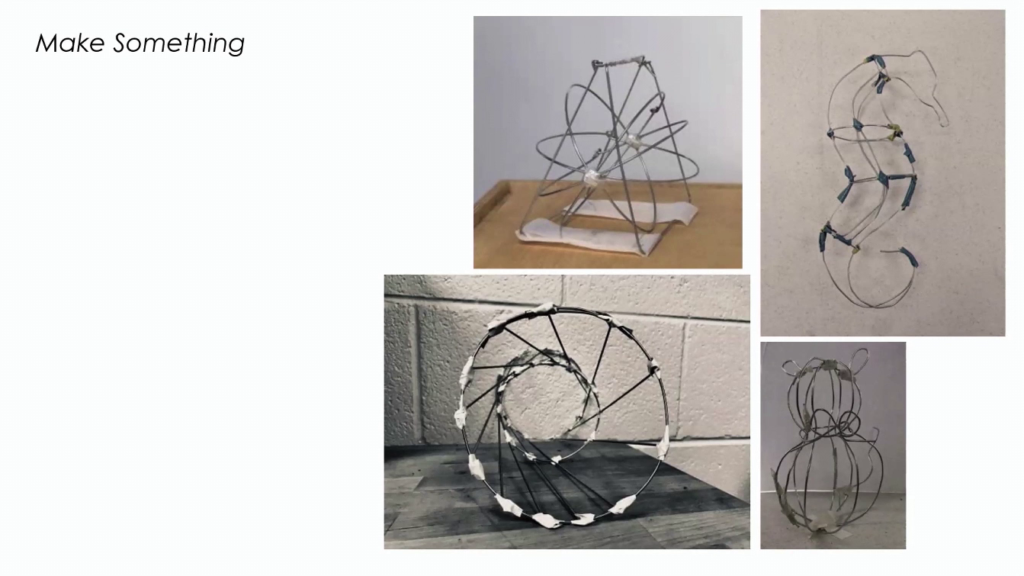

And so I did a few workshops with high school students and educators where…in part of, or I should say in starting it I usually just ask them to make something. Because they too have a voice, right. So give them the tools, the materials, and just make something. Just share your voice, just as I mentioned. You know, gift something. And so from that I’m able to I think see as well as they could see kind of where they’re coming from, techniques they might have or may not have.

Then I teach the technical knowledge. So I go through the Bailey-Derek Grammar, explaining how things work, why things are the way they are, how the grammar works, so that they can also use it in communicating the practice, right. So the theory, let’s say, behind the practice.

Then we go through certain steps in the grammar and practice technical skills that are involved in bending, wrapping tape, how you connect different materials, the technical skill in the practice is what we engage in and practice for a while.

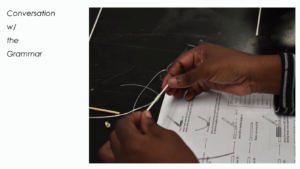

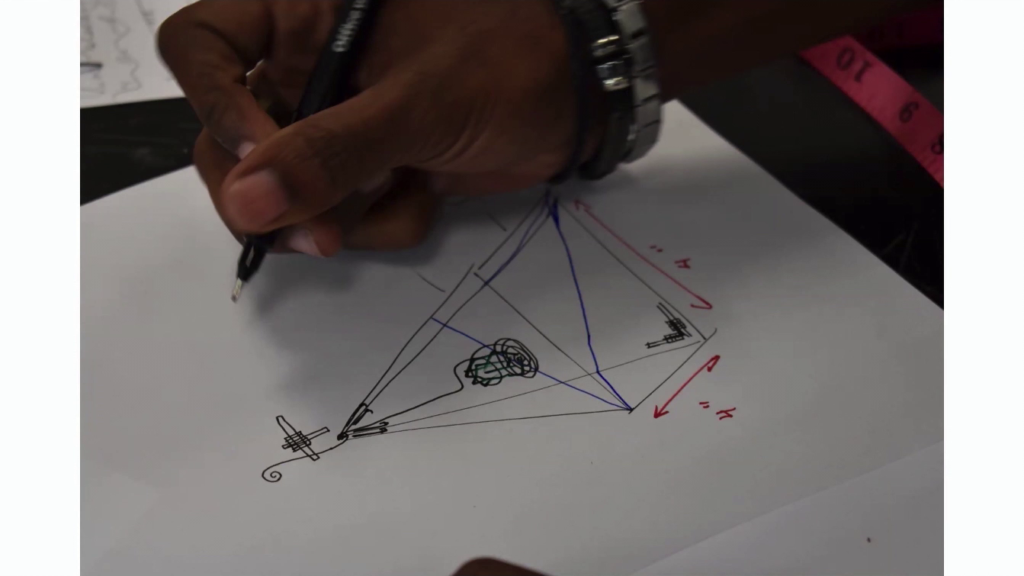

Then I leave space for them to have a conversation with the grammar. How does this thing work, right? What materials do I have? What connections might I make? So they spend time trying to understand it, figure things out.

Then we start designing artifacts and thinking through this grammar. So what do you want make, alright, And then going through the grammar how they may construct or build this thing. And there are no mistakes, alright? We’re all just learning.

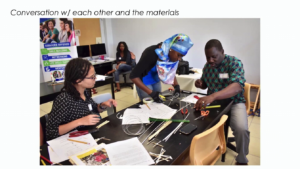

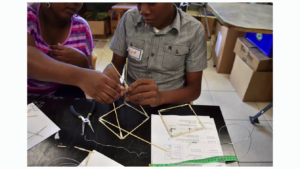

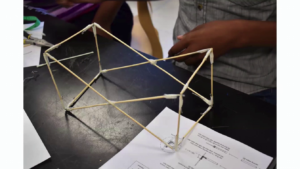

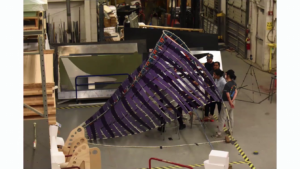

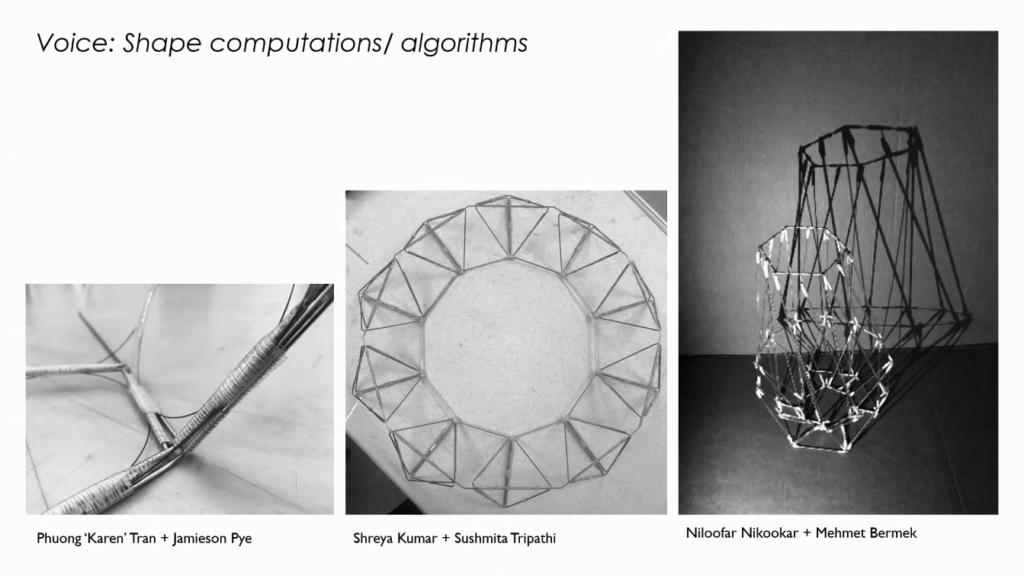

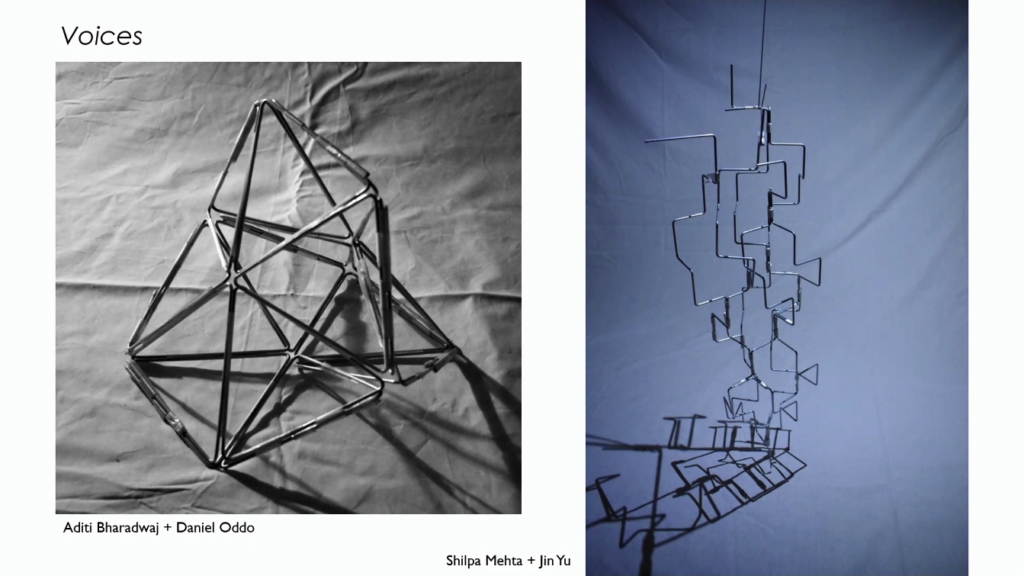

And so they continue to study the grammar, etc. Then they make with each other. And I’ll touch a little bit more on that later, but currently wire-bending is a one-to-one practice. So one person to one artifact. But because of the grammar, people are now able to make and build together, because there is now this tool around which they could discuss and make together. So here is a team of an educator and student making and designing together.

This is another image, making together with the grammar; educators and students.

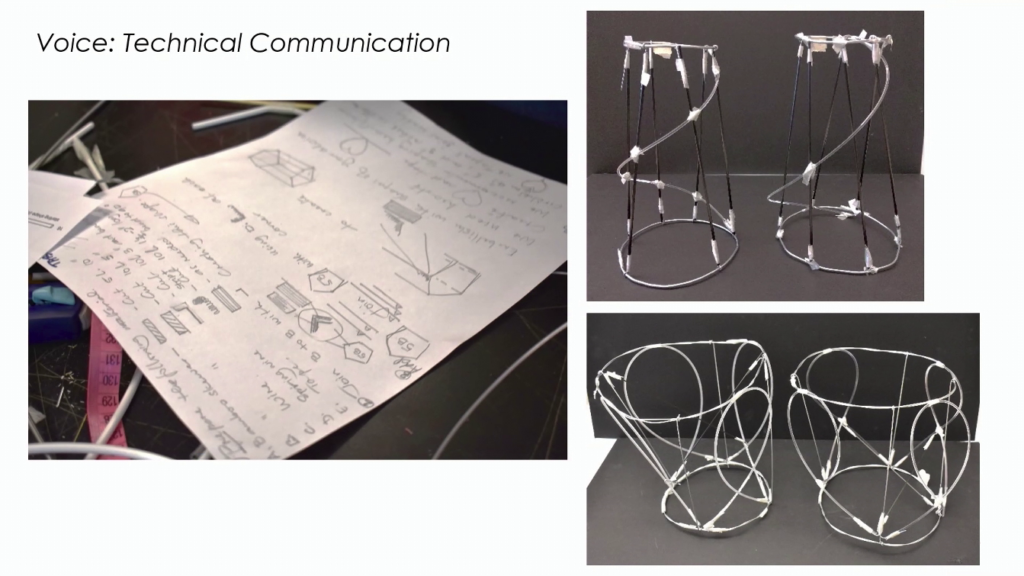

And then, using the grammar to communicate how they have done what they’ve done. Because a big part of this was testing the ability to communicate with the grammar. In this image, the top and bottom images, the artifacts on the left are original artifacts and the artifacts on the right are replications. So the ability to describe one’s process for making something is helpful, because then we could document artifacts because these don’t last for long; they’re temporary, as mentioned. But we can document design and making processes, and we could also teach others or share with others instructions, code, algorithms, for how we’ve made something.

And so it affords multiple voices to be working together in this craft for social interaction, social making, making together. So the idea or the goal, the desire, is that we give this gift, this voice, of making using wire-bending techniques back to people so that they can give gifts to their friends, back to their culture, their histories. And while this might not be digital code, it’s still code. It’s an algorithm, right. It’s steps for creating tectonics in this craft with this tectonic voice.

With college students, this is an example of a workshop seminar I did at Georgia Tech. I do the same thing. Make something. Let me see what your voice is trying to tell us, right.

And then through a more structured way of teaching, I ask students to make lampshades based on different methodologies that I’ve developed. So using the Bailey-Derek grammar always, right—so I teach that to them also—and then calculating design using shapes and always thinking of their interaction with light and shadow as well as materiality and how materials behave. Which actually takes a bit of a while for students to get, I feel. Because as architects we seem to design with things that are so abstract it takes us a while to understand that materials have behavior and how to design with that. So that’s what I really like about teaching craft in terms of listening to materials and how they behave.

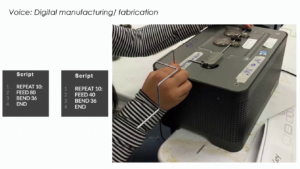

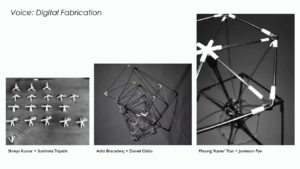

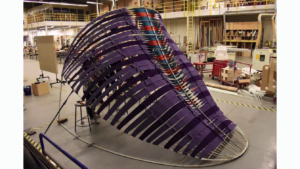

Then they learn digital manufacturing methodologies by using CNC wire benders. These are images of some of the processes and some of the wire-bent artifacts and designs that students made.

And another thing I want to mention, wire-bending is very male-oriented, though there aren’t many. So there aren’t many female practitioners. And what the CNC wire bender and these other ways of opening up the process, what it does is it has it opened up, at least in my classes, for female participants and younger people to engage in the practice, which is really old men usually practice it.

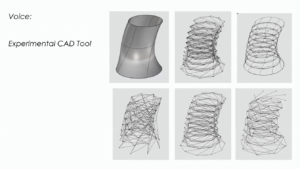

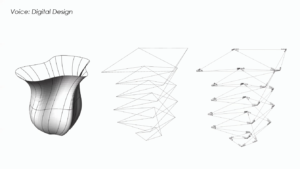

Then experimental software tools for digital design and fabrication, that’s another methodology that I use.

Then we explored at the scale of architecture. So what’s that voice at the architectural scale.

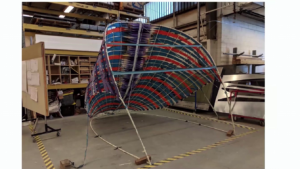

So here we made a pavilion using wire-bending techniques.

And so from this work of my interest in sort of linear materials, I make lightweight structures using pulling from many of these techniques. And since I’ve been at home, it’s the first time I’ve had my materials and tools home with me, so I’ve been able to explore and experiment in my own making, my own wire-bending artifacts. I love exploring them and their relations to light shining on surfaces.

And here are light paintings that I did as I was doing some wire-bending actions. I did these light paintings that I find interesting. I could say I like seeing how my body movies, or bodies move. Because they can ask questions of different bodies engaging in these crafts.

And I think that’s it. That’s all I wanted to share with you today.

Golan Levin: Thank you so much. This has been great. So, there’s a quick question of clarification. Andy asks could you explain a bit more about how the wire-bending tradition is dying? It wasn’t clear. You said maybe it’s done primarily by old men? But at the same time you also said that Carnival has been spread to all these new places around the world. So it would seem like maybe it’s thriving. So in what way is the wire-bending tradition both dying and kind of thriving again?

Vernelle Noel: That’s a great question, thank you. So it’s dying in Trinidad, for example, and in other places too. Wire-bending is hardly used as the practice. So people weld, or costuming is done by buying commercial parts. So the aesthetic of costuming in Carnival has changed. It is dying in Trinidad due to dying practitioners. So since I’ve started my work I’ve lost three—four of my sort of wire-bending knowledge experts. The craft, there is no way of teaching it, so we don’t have curriculum or pedagogy to teach it currently in Trinidad. So if I want to learn it I need to find that wire-bender to go to to learn it. So those are some reasons why it’s dying.

Levin: Kelly Heaton asks, “Have you translated wire-bending techniques into freefrom circuits?” She says like dead bug-style circuits, as made by artists like Peter Vogel. Have you thought about making sort of circuits that are made of wire that float in midair?

Noel: I wrote Peter Vogel’s name down, because no, I don’t know about that but thank you very much. I could definitely look at it. For sure.

Levin: Yeah, there are some people, Peter Vogel’s one of them, one of the better-known ones, who can make three-dimensional sculptures out of wire but actually the wires are things like resistors and electronic components that are soldered together in 3D space.

Madeline Gannon asks, “Can you talk about the temporary aspects of the wire-bent sculptures? The ephemeral quality. Do people who are learning want them to last forever, or are they okay with it being sort of destroyed, reused, invented? What’s the life cycle of these wire-bent sculpture forms?”

Noel: Good question. Thank you very much. So for Carnival, primarily you always start over every year. So, when people make costumes and dancing sculptures, if it’s a personal costume some people will want to keep it, right. So sometimes it depends on who makes what if they want to keep it. But otherwise, those who make them, the especially large ones, they want to reuse materials. So the ability to take them apart easily and reuse materials, that’s part of the [indistinct] desire to use adhesive materials that can be removed versus welding and other more permanent connections.

Levin: Iman [sp?] points out that the use of wire-bending allows the opportunities to make minimal surfaces with soap bubbles, and there’s probably some really amazing forms that are yet to be explored through techniques like that.

Pipo [sp?] asks a technical question, which I think you very quickly mentioned “Oh yeah, so my CNC wire bending machine.” But I think many people have not seen those before. And Pipo’s questions is, “What’s the software that you use for the CNC wire bending machine? And what’s the machine you used?”

Noel: So it’s a machine from Pensa Labs. It comes with its own software. It takes…the file extension, I can’t remember. But it just takes 2D parts, and you could also script bend or feed. But how it really helps me is in particular the harder wires. So for smaller artifacts I could bend by hand. For others it’s very labor-intensive, and so the ability to have a machine doing that really helps when it comes to that part of the practice. But you can check it out: Pensa Labs CNC wire bending machine.

Levin: CNC wire bending machine. I’m just looking at the questions here.

“As an architect how do you think about scale with respect to your work on wire bending? From the photos it’s clear that some of the possible objects are quite large.”

Noel: Yes. So, that project I showed, the pavilion that we made, that was exploring it at the architectural scale. And as you saw, I think I quickly went through that because the clock scared me. There were new tectonics that had to be developed, but also tested. So we did structural testing on these tectonics to see if and how they would work, so that we knew that they could be applied at the architectural scale. But that would be something that I continue to explore, what these large implications or possibilities might be for the tectonics of wire-bending to be present in these cultures.

Levin: Another question from the chat. “Are the small-scale maquettes proof of concepts, or ways to refine a design? Or are they objects that stand alone in themselves?”

Noel: Which ones? The last slides, maybe?

Levin: I’m not sure actually from the question. I guess I mean, when you’re working students, they’re developing like lampshades, which are finished projects in themselves. Do people who developed the large-scale things for the carnival, do they make small ones first?

Noel: No. So, because… Yes and no. It depends on the process. Because Carnival…thought it’s a year, it takes so much resources, many times it’s sort of a full-scale prototyping process. So they might prototype certain moments of it. But a small sketch or a small idea that might be done to sort of test the idea of it? Rarely did I see any small things. Some people made from things that they drew, directly. Some made without even drawing, right. So it depends on how they do it, but very rarely are small prototypes made.

Levin: There’s one person who’s observing in the chat that they had never heard the term “grammar” in a craft context before. And another person observed that it’s lovely that you…did name the grammar after the people from whom you learned it?—

Noel: Yes I did, yeah.

Levin: That this was like yeah, A #1 to name the grammar after people.

What was the process like of extracting the grammar from domain experts who might not be using that vocabulary? They probably didn’t say “Oh yes, I have a shape grammar,” you know, for talking about that.

Noel: Yeah. It was nice in that our discussions— So I would spend days with these people and we would each, we would chat. I would look at what they were doing, analyze their artifacts. So it was a process of taking a lot of images and analyzing the things that they’d made, asking them why certain materials came together, or why they did certain things that they did. Great discussions on the histories and where they thought the practice was going, what it meant, what Carnival meant. It was just a nice relationship-building, and still is.

And so I took the grammar back to them, to show them this is what we have now. And Albert Bailey, he was like, “Ooh. I understand this. I could use this.” And another designer who does a little wire-bending, he says, “Ooh, this could help me. This could definitely help me.” So their reception of it was most definitely—

Levin: Well, you’re providing them a formalization of what they had presented to you in a less formal way.

Noel Yes, absolutely.

Levin: I think your work is really lovely with the Carnival in particular in terms of the way that it shows people developing technologies and crafts in ways that first of all come from very old craft languages. And illustrates a way in which people are making things for themselves and also for their community, you know, for their family and friends. It’s really an important way to remember that we can be developing things. And I hope you get to find a way to make a gigantic wire-bender to make really, huge huge automatic shapes.

With this we have to wrap up. In just two minutes we’re going to be hearing from Hannah Epstein. I want to thank Vernelle Noel. Thank you so much Dr. Noel.

Noel: Thank you so much.

Levin: And we’ll see soon, okay. We’ll be back in two minutes, everyone.

Noel: Bye.

Levin: Bye.