Golan Levin: And welcome back, everyone. This is the Friday evening session of Art && Code: Homemade. My name’s Golan Levin, director of the Art && Code festival, professor of art at Carnegie Mellon University. And I’m thrilled to welcome you to our evening session. We’re going to have three presentations. It’s five o’clock Eastern time where I am, and we will be shortly hearing from Leah Buechley and Nanibah Chacon. At six o’clock our time, one hour from now, we’ll hear from Kelly Heaton. And then at 6:30, we will hear from Virginia San Fratello and Ronald Rael.

It is now my pleasure to introduce collaborators Leah Buechley and Nani Chacon.

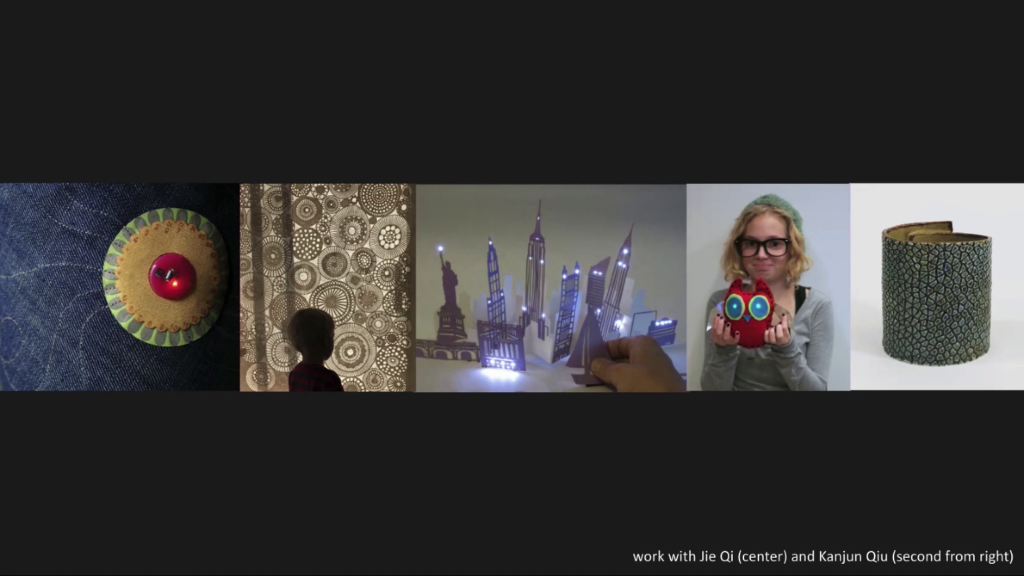

Leah Buechley is a professor at the University of New Mexico, where she directs the Hand and Machine research group. Her work explores integrations of computing, electronics, art, and craft. She is a pioneer in paper- and fabric-based electronics, and her inventions include the LilyPad Arduino, a construction kit for sewable electronics.

Nanibah Chacon is a Navajo/Chicana painter and renowned muralist whose work is oriented to community-based arts and education, and sociopolitical issues affecting women and indigenous peoples. Following a decade-long career as a graffiti writer, Nani shifted to large-scale public works and murals, a natural progression that extends from her personal philosophy that art should be accessible and a meaningful catalyst for social change.

Leah and Nani have been collaborating, and we’re going to hear about that now. It’s my pleasure, please take it away.

Leah Buechley: Great. Thanks, Golan.

So today, Nani and I are excited to talk to you about a collaboration around designing and building interactive murals. And I should say as a preamble that this collaboration is really just starting. And so we’re excited to kind of talk to you about the early stages of this project, and then I hope also have a little bit of a conversation about it.

I’m gonna give a short overview of my work and some of the precursors to this project, and then Nani and I will kind of trade off and go back and forth.

So just a little bit about me and my work. My work takes place at the intersection of kind of technology research along with kind of material and cultural research. I’m really interested in exploring the relationships between materials, culture, long-standing practices of how different cultures work with different materials, and then integrating that with technology to give rise to kind of new creative opportunity for all sorts of different people and kind of different perspectives. Anyway, that’s a super brief overview.

I wanted to talk a little bit now about our project and the precursor projects to it. So, we’re planning to work together to build these very large-scale murals that have embedded electronics and interactive capabilities due to the fact that they’ll have these embedded electronics and embedded computing capabilities. Part of the impetus behind this project was a series of projects that I worked on when I was a professor at MIT with my graduate students there. So we designed and built a series of interactive wallpapers? So these were large-scale surfaces that we painted using conductive inks and paints, and then built custom electronics to kind of attach to these different wallpaper surfaces to explore what very large-scale kind of ambient interactive surfaces…like, what could you do with those, both kind of aesthetically and also playfully, and also kind of functionally. How might surfaces like this…what might it mean to have a large-scale interactive surface kind of embedded in your home that could provide like, lighting and speakers and kind of electronic functionality, along with some sensors about the environment and the ability to kind of interact with all of the network devices in your house in this like, physical kind of ambient way.

So we constructed these artifacts and then programmed them with a range of different applications and games and so on and so forth. The previous image was a close-up of one of the wallpapers. This is a larger image that gives you a sense of the scale of some of these pieces. And again I wanted to just highlight the fact that this is kind of painted on a very large surface using a mixture of conductive inks and paints, and then traditional paints, and then we’re able to attach electronic components to the surface of that painted wall using things like screws and magnets and stuff like that.

So the plan for our collaborative project is to use some of the lessons that we learned in our material-based research, our design research, and also kind of the interaction design research that we did for this series of projects, and then take it and really expand it and also make it something completely different, working on a much larger scale even than these projects were, outdoors. And also in a very different context. So these wallpapers were intended to be used and built kind of in the home, in this intimate private setting, and of course murals are a completely different can of worms. So murals are these outdoor, very public displays that are often rooted in a particular community and a particular history. Oftentimes—and I’ll hand things over to Nani in a second and she can talk more about all of this—but oftentimes murals can communicate in an almost narrative way something about the history or important kind of cultural context of a particular community. And that is very different from what you would expect from the wallpaper in your home. So we are just starting again to think about how all of these different threads come together.

I might talk a little bit more about this in a second, but I’ll mention that one of them, an ongoing one for me, is an interest in and excitement about the materials that go into this project, and the meaning of those materials along with the meaning of this larger project. So I’ll come back to that in a bit, but Nani I’ll hand things over to you.

Nanibah Chacon: Hi, everyone. My name is Nanibah Chacon. I’m a muralist. I’ve been doing this for about twenty years. And right now the focus of my work is doing large-scale pieces that are community-based and site-specific. And what I do with these works is…I like them to work less in the way that a traditional mural works in kind of a historical context that kinda gives the narrative to maybe a story or a history of peoples, and really use this platform and this medium to provide a question that then the community comes to answer. And that question to begin with is begun with the community also. So it becomes this exchange of kind of working back and forth, and therefore it always needs an audience. And I think that creating work in this way, murals work the best for this medium because they are completely accessible.

This piece right here is… I put this slide in here because this is actually an arts and technology piece that I had created about ten years ago. And it’s titled “She Taught Us to Weave,” and it’s manifestations of Spider Woman. Spider Woman as a deity that taught Dine ask people to weave, which was really a tool of sustenance. And this mural itself was embedded by low-powered FM radio, so that way it was transmitting, and really wanted to think about the context of using tools and using the idea of the electromagnetic spectrum as a way to one, kinda act as a trap; that you always have this viewer in front of you, a captive audience. And then what is that spectrum kind of imposing on them?

So, what it’s actually transmitting is a prayer. And I collaborated with my sister. My sister builds transmitters. And we had— It’s funny—this is just kind of a side tangent—is we had kind of looked into the materials that Leah had mentioned just a second ago and like had no idea how to use them. So, we kinda guerrilla’d wiring this and hooking up some solar panels on the roof, and building a transmitter outside.

So, this is a very large piece. I wanted to give a detail of this work but also there’s— If you want to go to the next slide also, Leah, then you can see the pan-out of the entire mural. And this mural was created by children at Washington Middle School here in Albuquerque. And really it was relying on the students to help dictate the content of this mural, which was finding empowerment. So a lot of the times I work with these overarching concepts and then hone them into an idea that is kind of cultivated over time. And in thinking of empowerment, what we did was we researched these plants that were growing up around their neighborhood. A lot of them are categorized as weeds, a lot of them are kind of these nuisance plants. And then we took ’em to an herbalist that was in the same community and she identified their medicinal properties. And for us, me and the students who were working on this, this is the way that we were able to one, empower these plants but also empower the students with knowledge that they are then passing along and kind of honoring these plants that you would normally dismiss or even pull out and throw away. So, I wanted to show this piece to show the interaction between community and it starting from a community focus, and using it to answer questions and create dialogue.

This is another piece. And this is an interesting work. A lot of the works I do are in relationship to the spaces that they’re in. So, I try to create that dialogue with me as the artist but also the people of that community, and the conversation that we might have in between that. So of course you can see this is at the El Paso Museum of Art. And I did this piece about the river that joins us, of course the Rio Grande, that travels all the way up through the Sangre de Cristo Mountains all the way down and ends in Juárez. And really, our relationship to the water, and our relationship to the history of the water, and the water that flows between us is really water of millions of years. And the water that’s inside us.

And the interesting thing about this piece was that we also were able to collaborate with a small group that was working on augmented reality. And they used this work as a teaching tool, and it’s paired with a program for augmented reality. So you could take a cell phone, download their program, kind of scan across it. And they did a series of murals that were done in El Paso. And on this one in particular— Actually it works with almost anything. If you probably even screenshotted this and then did it, you could look at it. Then the plants move, you get actual sounds of the river. They went and took some soundbites of the river. And you get an overview of some of the silvery minnows and some of the plants, and some of the history.

And yup, that’s all I have for slides of my work.

Buechley: Okay great. So, we thought we would take the last part of our talk here to just talk a little bit about the collaboration and kind of what we are most excited about and interested in in coming together for this collaboration.

Here’s a little kind of mockup of…I don’t know, potential mini interactions that might take place. This is another close-up of that initial mural that Nani showed.

For myself, I wanted to talk a little bit about the different aspects of the collaboration and what I’m excited about. One of the things that I feel most interested in and excited about is learning from Nani and kind of expanding my own knowledge and understanding through this project. Both in terms kind of designing and making a meaningful and beautiful piece of work that occupies this really different kind of space and this really different kind of meaning for people. But also there’s this kind of third component of the project which we haven’t really talked about yet, which is our plans to collaborate with youth around the city of Albuquerque to kind of collaboratively design and build murals. And this is something that Nani has a tremendous amount of expertise in and that I’m really looking forward to kind of bringing youth into this process and have them participate in this process and also my hope is that this may be an opportunity to present kind of technological tools to youth and to other community members as a creative tool that maybe looks and feels differently than the stereotypes that folks might have in their heads about what technology is, and what you can do with it, or what you might want to do with it. So anyway, those are after a few of the things that I’m really excited about.

Nani, I’ll hand things over to you.

Chacon: Yeah. I for one was very very excited when Leah asked me to collaborate on this project just because of the new…I feel like it really is a new horizons for public art. Definitely I’ve worked in a large capacity of creating lots of different types of public art pieces aside from murals. And I am really interested in what technological components can add to content and the way that we…internalize those concepts? I really think about the way that we use technological tools right now, and I really feel that they are still very much on the utilitarian level. And this is I think a project for me that shows that shift between being utilitarian into art, and becoming something beautiful, and becoming something more. Becoming something aesthetic. And for me that really is an increase in the way that we think, the way that we see the world, the way that we participate in the world, and also that we see and receive knowledge.

So, all of those horizons for me I think are just very exciting. And one of the things that I love about creating work in the way that I do is that learning is a huge part of my process. I think it’s the reason why I choose to create work that’s collaborative with community members, and with students, and with children sometimes, or elders, or really…you know, anybody. Because I think that I learn a great deal, and for me that’s important and I think that that really facilitates the growth of my practice and creating new pieces. Each piece that I make kinda builds upon itself, and I think in the whole scope of everything that including students in that is very essential. Because at some point you know, it’s great when you have something new and you do something new, but if you’re not really passing on that knowledge or the cultivation of that knowledge, then the next phase of it can’t really go anywhere. So, I’m excited to embark on this with Leah and be able to not only facilitate new ways of making art but also new ways of thinking.

Buechley: What you just said, Nani, made me just think about like… I mean, I’ve already said a little bit of this, but one of the things that just so much resonates with me, and one of the things that I feel like has taken me a while to learn and that I now feel so passionately about, is the way that we as a society often approach education? as…I don’t know, there’s a big component of education that is rightly like passing on knowledge that we’ve already gathered, right. That’s like a huge component of education.

But I also think a wonderful…often overlooked opportunities, in education are involving new people in like genuinely new work, and genuinely new exploratory processes? And one of the things that I’m most excited about for this project is to be involving like kids, and youth, in this project from the very beginning in developing this weird technology that has never existed and we’re not sure we really know how to build, and having them be part of that genuine technological and artistic discovery process from the ground floor is something I’m just really excited about and I think is just an exciting and really fulfilling way to approach education in general. So I’m excited about that.

Chacon: Yeah, I agree. I also have a background in education, and that’s always been kind of when— I agree with you in that it’s often overlooked, and not valued sometimes. Sometimes we can get even stuck in the tropes of the way that teaching is facilitated.

But yeah, I’m also really interested in…you know, every now and then just to let the audience a little bit in on where we are in the process, even though it’s quite new. Is like hearing the capabilities that are even possible. And for me, thinking about a wall that can… Of course I look at public art as being interactive, that you need an active audience to participate in— We see a lot of public art pieces on the Internet but it’s like, go out in the world and look at ’em, because they’re meant to be experienced on large scale, and I think that that’s the impact of seeing work like that.

But, to think about the capabilities that technology will have in our public spaces, and for that to be accessible. And you know, Leah kind of touching on that with how at the first attempt it was really about creating some— You know, she had made a prototype that was wallpaper in a home but really reaching upon that and thinking about the accessibility of…that it shouldn’t be limited to one person or one household, that really it should be kind of out there for everybody. And for me that’s really important because that then kind of breaches on the way that we begin to think as a society, the way that we begin to think as people, and how we are bringing together and cultivating concepts within that.

Buechley: Now is maybe a good time to open things up for questions or comments from the audience.

Golan Levin: And here I am. Thank you so much, Nani and Leah. There are a bunch of great questions coming up in the chat here. I have a question I’d like to start with, which is sort of based on my own intuitions as a person who creates interactive art.

It seems like there’s multiple scales at play here in your eventual collaboration. I mean, Nani as a muralist you’re used to making things that are to be perceived from actually a fairly significant distance. And at that scale, you know, augmented reality could make sense with a phone or something like that.

But Leah, you’re accustomed to making things that are tangible and up close. And in the wall-like work that you’ve made it’s like you’re really up there. And in the picture you just show this person who sort of like right up against the wall.

And I’m curious what sorts of thoughts you’re having about whether the mural is something that people interact with or experience, in this technologized way or in this expanded way, from far away or from up close, or even both or where—how you’re bridging the kind of scales. And especially Nani, because this could be very new for you if you’re making…have you made murals before that people could appreciate or interact with or experience from way up close with little details that they can kind of read?

Chacon: Yeah. I mean the work that I showed of course is…you know, a lot of them are pretty large-scale. Like, I think two of them that I showed you are you both twenty feet high and over a hundred feet long. But yeah, walls come in all shapes and sizes. And I think that the walls that we’re currently looking at are ones that are on the pedestrian level. You know, ones that would be on a sidewalk. And actually that is the size that actually I think in a cityscape or somewhere where there’s a lot of pedestrian traffic, those are a pretty tangible size of walls. And the design process is different, you know. I mean even in creating a mural, you create for what you can see and what you can experience. Some walls are meant— Larger ones of course you’re going to be larger with detail and content and the way that you design that. And with a smaller wall you have a lot more intimate of an audience and the detail is a lot more intricate. So I design for the space, for the space that’s needed.

Levin: Other question sorta related to that. What are some ways that you wish people could interact with a mural that you don’t have technologies for yet?

Chacon: Ooh, that’s so hard. [laughs] I don’t know. I don’t know what I’d— Yeah, I mean I think that there’s so much with… For me it’s really that tangibility, right? And I think that 2D art is always just meant to be looked at. But what other ways can we internalize that, maybe thinking about sound and sound capabilities? I think sometimes I’m interested in the way that we bridge concepts, and the way that concepts can come together to create different meanings. I don’t know if that makes sense. But maybe the way that sound or light isn’t just used as something that is kind of entertaining but really something that adds to the content and adds to the facilitation of the question or the work itself.

[Levin and Buechley interrupt each other]

Levin: Sorry, Leah. The chat is hopping with great questions. Please go ahead.

Buechley: Oh, just a quick comment to that. Which is to push back on the premise of the question, a little bit. One of the things that I think is a wonderful and fruitful way of working and that I’m looking forward to Nani is that the existing technology, we have a beautiful rich palette. And we’ve just never played with it in this context. And there’s so much to do there with the materials that we have at hand. And I think the most interesting thing here is not some fancy new technology? It’s actually in the integration, and in the conversation, and in thinking about things like what we can actually build right now. Anyway like, to me that’s a more interesting place to put attention. Not that the other thing isn’t interesting.

Chacon: That was a [inaudible] way to put it. Thank you, Leah.

Levin: Another question from the chat, and this is really about the content, in a way, of such a mural. The person asks, given recent controversies around Confederate statues, how do you think that a technology-based mural could open up new opportunities for engaging public acceptance of or criticism around public art symbolism? Like are there ways the technologies and the augmentation could open up greater access to critical content.

Buechley: Right.

Chacon: Yeah. I mean I absolutely do. I think one of… It’s hard to base…I think all public art into the realm of what the purpose of Confederate statues was for. And I think that there is the slippery slope that begins to talk about like, public art as kind of offensive, or we should take it down, or not take it down, and what’s really being said. And for me that’s…the technology side and the artist side is why the integration of community and community collaborators is so important, is that whether we’re using technology, whether using just paint, that we are facilitating this content in a conscientious way that is layered. And that really begins from not trying to tell anybody a history or uphold you know, somebody we think is important or should be upheld. But really that that content is coming from the community itself. And that it’s made in that conscientious way of kind of being maybe a feedback loop of something. That’s my intention with work, is that it’s made to express a dialogue that is then giving out something and then receiving something. Which in a weird way is kinda like a technological pun, also. But like, that’s the way that I think about the works that we’re creating. So I absolutely think that public art in general, but also that the facilitation of these technological components can do that.

Buechley: And just a little comment also. One of the things that is interesting about this project that we’re encountering already is not only the physical large-scale but the time scale as well is over long periods of time. So working on a project that will be installed over the course of many years…we’re starting for example to do technical material tests just to see if our electronics can withstand the outside environment over long periods of time, like over the course of many years. And I mention that because I think one of the exciting and interesting technological possibilities here is to potentially relate to time and change and ongoing interaction. And of course the mural itself changes over time the longer it is in a space and it degrades, plants grow up, people get used to it, whatever. But the artwork in all sorts of ways is evolving, but the electronic element can have its own kind of evolving kind of history of interaction, and I think there’s just a lot of richness there to explore in the time scale and how people relate to the mural over time just to explore there, that could relate to that question.

Levin: Leah, one thing that wasn’t— I don’t think it was explicitly mentioned in your presentation together was how did you two meet? Or how this arose. I realize you’re both in New Mexico, but how did this come together?

Chacon: Leah found me. In [indistinct; laughs]

Buechley: I mean this general project, I’ve had this like…since we kind of worked on the wallpaper project I’ve been like oh, I’d really love to try working on a mural project at some point. But I don’t know…I can’t do that like, by myself. I would need a great collaborator. And so when I came to New Mexico I just asked people that I knew like, “Do you know any muralist who might be interested in collaborating with me and whose sensibilities, we would have a good alignment there and raport and stuff.” And a friend of mine recommended Nani. And then I looked at her work and I was like oh, it’s so gorgeous! And so, yeah. So I was really happy that she was interested, too.

Chacon: Fate.

Levin: I’m going to field maybe two more questions then we’ll then wrap it up. So Nani, how do you manage all of the sort of hands involved in the work of making a mural? It not just for a community, often it’s by a community, or a community’s involved in making it happen. Something that’s a hundred feet long, twenty feet high…you’re not painting it all only by yourself, right? So tell us about—

Chacon: Oh, like the process.

Levin: The process and also how that process might be…wrinkled in an interesting way by the new collaboration as well.

Chacon: So I do have a background in teaching. And I think a lot of the mural process like in these larger pieces that are a hundred feet long, I often have an assistant. And they’re already painters, so there isn’t too much…of course there’s always a teaching capacity in there. In the Washington mural in particular I worked on it over two summers with students that were at the middle school themselves. So you know, it was a group of twelve students. It was with Working Classroom, which is also the collaborators that me and Leah will be working with.

And part of that was I taught a workshop to the students that I had. And I taught them how I painted. I walked them through my process from start to finish. And they painted with me, you know. And then there were moments that of course me and my assistant, we would go through and kind of tie things together. That makes it interesting for me, because in the finished product you see it and it looks great and there’s…you know, it’s a finished product. But for me I definitely see their hand in there. I see the students’ hand. I see a 12-year-old hand. And I think that makes it beautiful. I think that that’s a different way of that mural looking, of that painting looking, that is something that I couldn’t necessarily create.

So I celebrate that. And I think that there is a great deal of teaching and literacy that kind of comes—a kind of meshing of style and maybe that give and take a little bit in the process. Because you have to compensate and you can’t always think everybody’s going to do everything the way that you want it done.

As far as other community collaborations, every time I work on a mural— And I think this is important to say because sometimes I think the idea of a “community-engaged mural” means that everybody came and painted the mural, and that’s not necessarily true. I mostly paint the product. That’s the finish. But the community engagement part can take all different shapes and forms that develop the content. And for me the content of the work, the thing that makes the work stand, is the content. And that’s the part that takes the care. And that’s the part that I bring the community in.

So sometimes that can be…you know, I’ve worked with traditional language-keepers, and I’ve worked with elders, and I’ve worked with people who are in rehab facilities, and people who are going through different stages of life in groups. And you know, it’s all different forms of the way we develop this content or get to know each other and facilitate this. Almost every time it’s different because every situation and every person is different. So sometimes we create other kinds of art together before we get to this process. So yeah, there isn’t like, kind of one thing to that. But yeah I think that mostly it’s a give and take process. And at the end of that, that’s kinda how the collaborations come together.

Levin: Thanks. And then Leah, the last question I have is for you. We’ve known each other a long time. And I think it’s really fair to say you’re a pioneer in the field of hand and machine, or you know, high-tech/low-tech. You’ve been at this a long time. LilyPad Arduino was I don’t know, fifteen years ago or something? We’ve been through the maker movement, and you know, we’ve outlived Make magazine and all that.

And I guess this question is…I mean it’s maybe not a state of the union but more of a personal perspective on how your relationship to the sort of landscape of hand and machine work has changed since you’ve been working in it. This is also in the following on some of what hannah perner-wilson spoke about this morning in terms of her ambivalence in relationship to the e‑textiles field as you know, sort of post- Google Jacquard post- her textile shop, her tailor shop. Like, we’ve come a long distance since you began in the field, and I’m sort of curious to know where you’re at now with it and how you feel about it.

Buechley: Wow that’s a big question. Um… I… Overall I would say I feel really happy and excited? I feel… I don’t wanna— When I started doing this kind of work…again like, now that’s been a long time ago, like it felt like what I was doing was weird and there weren’t very many people exploring things like this. And now that’s really not true. There’s I think vibrant, beautiful work happening at these intersections all over the place? And that is really incredibly…just delightful.

I don’t know that I can take any credit for that, per se? Like I feel like there’ve been all sorts of things that have led to that outcome. I mean a lot of like the word STEAM and work that has happened under that umbrella. Seeing some of the foundational work—and you know, I think despite some of my criticisms of Make and stuff, the maker movement helped get a lot of stuff out into the larger world outside of just like, academic research labs. And that has been really exciting and interesting to watch happen.

So I…I share I think hannah’s… And hannah’s such a brilliant and amazing artist and person and technologist and everything. I share some of her ambivalence about e‑textiles in particular? I feel essentially no ambivalence about this landscape of finding creative ways to work with technology and engage long-standing making practices and a range of materials kind of in our work with technology. And I think there’s tremendous…there remain like incredible creative opportunities there for art and design but also just for just like, technology development. I think a lot of the most exciting work in HCI and in design, frankly, is happening at these intersections, kind of blending what we know about making with all sorts of different materials and kind of blending that with new technologies.

So anyway, so I don’t— I feel very…remain like super excited about and engaged with this larger field. I think, again…specific projects where if you stay in the domain too long I get restless. E‑textiles is one of them. I just assume—like, I don’t want to do that anymore, basically. But there are lots of beautiful, awesome things that I do want to do.

So I think it’s great. I mean, this conference is like one big chunk of evidence about how great it is, I think. I’m delighted. I’m excited.

Levin: Thank you so much both of you, for sharing your energy and your work and your…just the…we’re all— This is going to be a very portentous and very exciting collaboration. It’s lovely to see it at this early stage. We’re all gonna follow along, I’m sure. Thank you so much for sharing your energy and work with us here. During short days and dark times it’s really lovely to see this kind of inspirational approach.

So with that I want to thank Leah and Nani. Thank you so much for joining us today here at Art && Code. We’re gonna pick it up in about fifteen minutes at six o’clock PM Eastern time with Kelly Heaton. So I’ll see you all soon. Thank you so much.