Golan Levin: And we’re back. I’m Golan Levin, director of the Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry at Carnegie Mellon, and director of the Art && Code Festival. This is the final presentation at Art && Code: Homemade: Digital Tools, Crafty Approaches, Janury of 2021. And our final presenter tonight is Kelli Anderson.

Kelli Anderson is an artist, designer, animator, and tinkerer who pushes the limits of ordinary materials by seeking out possibilities hidden in plain view. Her books have included a pop-up paper planetarium, a book that transforms into a pinhole camera, and a working paper record. Intentionally low-fidelity, she believes that humble materials can undo black boxes and make the magic of our world accessible. Ladies and gentlemen, and all friends, Kelli Anderson.

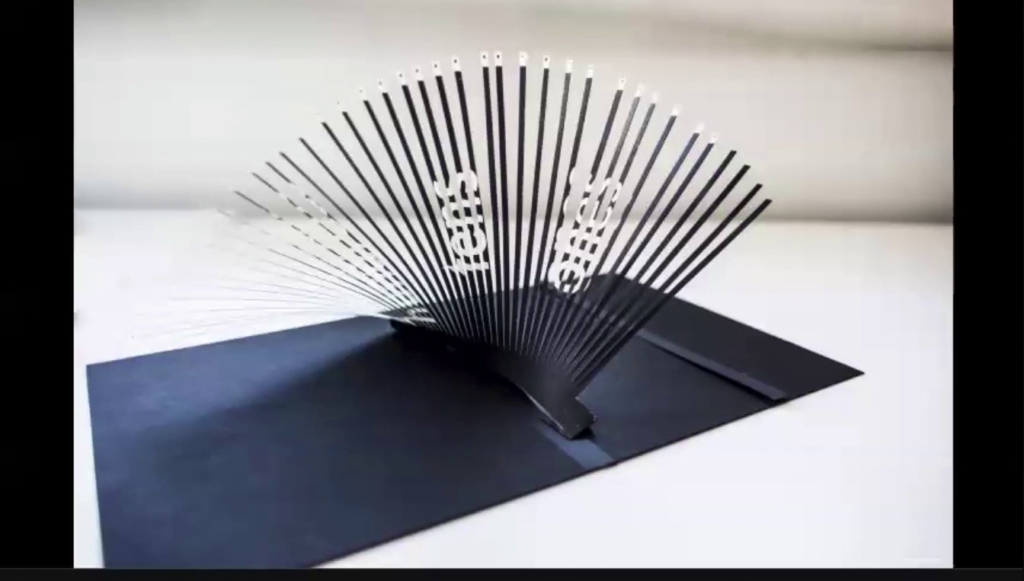

Kelli Anderson: Hey you all. So, I wanted to start here with the paper animated GIF that I contributed to the awesome zine that we collectively made. So this is a good thing to perhaps print out at home and make for a friend who needs a little help remembering not to doomscroll all day.

So, thank you so much for having me, everyone. So I’ve been making homemade things from my one-room studio apartment for over a decade now as I’ve been working as an artist and experimental printmaker.

https://vimeo.com/134406960

A coder and animator.

A professor and author.

https://vimeo.com/330362087

A papercraft music video maker.

And within these four walls, I’ve worked on secret brand redesigns from my desk.

And then I’ve also designed everything—logos, menus, bags, wallpapers, architectural facades—for things like this one hundred year-old bagel and lox institution called Russ & Daughters. This is a facade I designed in Photoshop, which is not ideal but definitely scrappy. But we completed our third restaurant together in 2019. So, it’s working out.

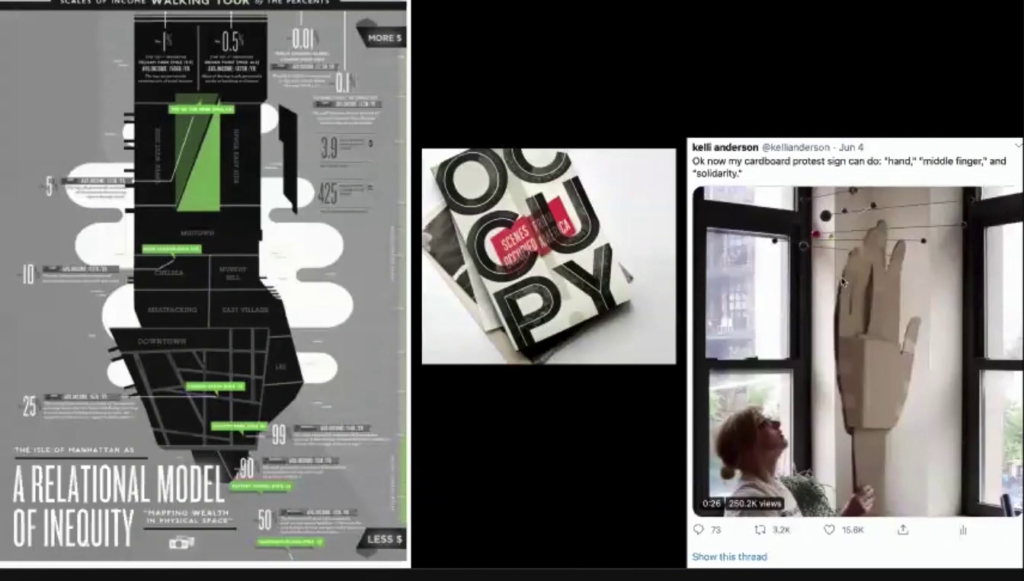

I’ve published two books from my desk here.

And I’ve participated in small ways in two of the major protest movements of my generation, Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter. So I feel like staying homemade, and staying small and sort of in control of my path hasn’t limited what I’ve been able to do but rather has allowed me the freedom to show up for the occasions and life and culture that really matter to me.

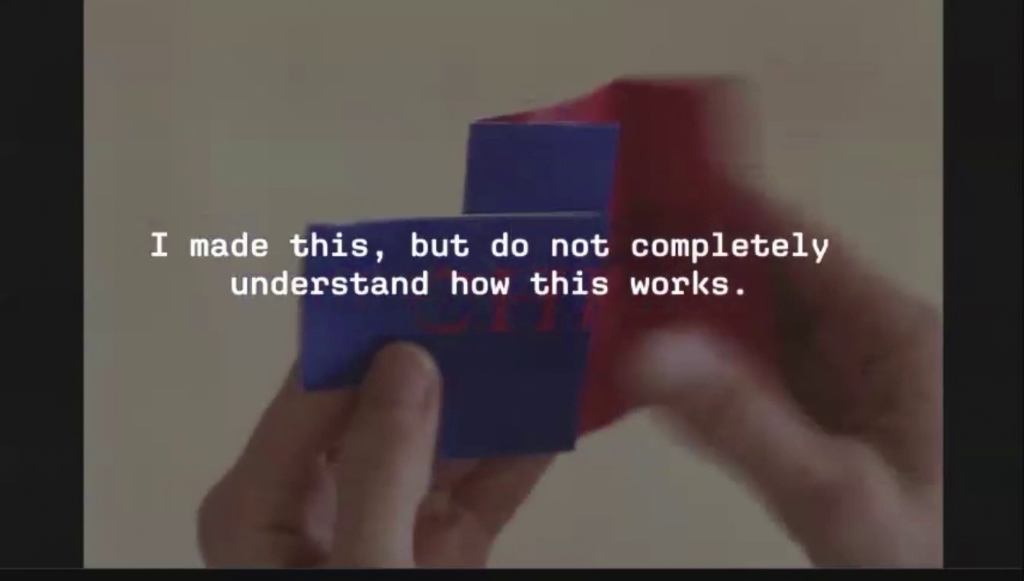

And like this paper animated GIF, I can’t say for sure that I understand exactly how it works? I can only understand the flexagon from frame to frame, really, and I never have had even more than like a one-year plan for my career? But my hands found a way to make it work and I can show you the extremely scrappy way that I make the things I do.

So for me, having the freedom to explore and tinker and wander to advance the plot has felt really key. And I want to acknowledge that having the capacity to allow such uncertainty and anarchism into one’s life is not a privilege that everyone has.

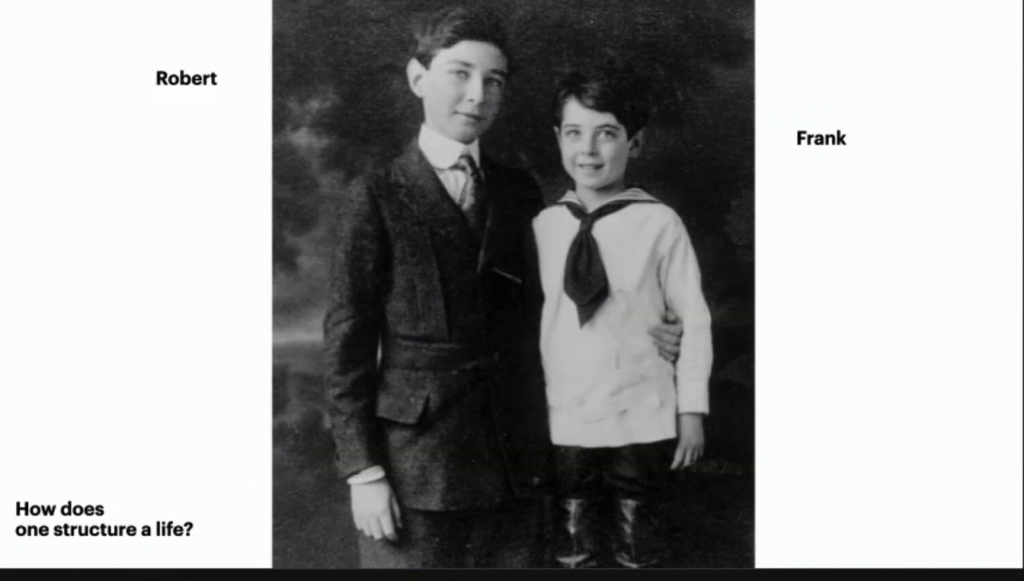

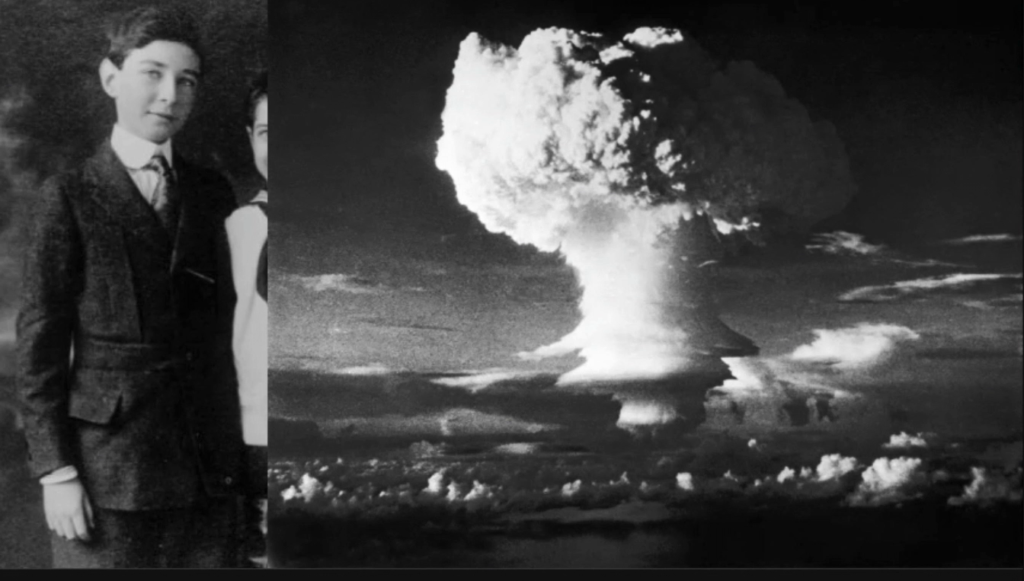

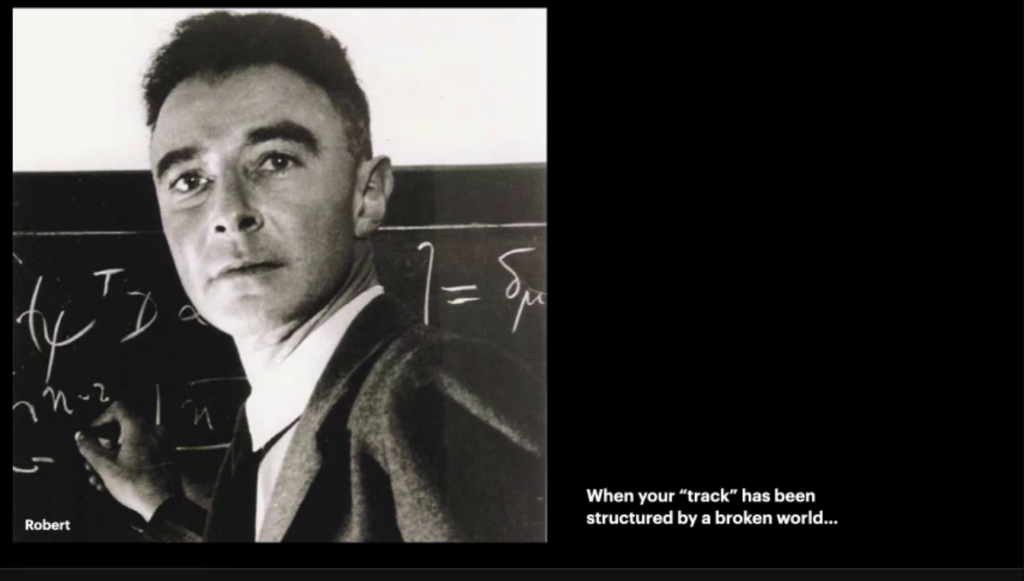

An interesting case study in the question of how does one structure a life and career are these two brothers that I feel all of the contrast in the world resides within. This is J. Robert and Frank Oppenheimer. And both started out with this preternatural talent for science. Both were headed on a track, destined to become top physicists in their field.

And Robert succeeded on every count. He sort of garnered every professional vestige of success. He rose to the very top of this field, leading the Manhattan Project and he became the father of the atomic bomb. And Frank, while equally brilliant, was completely banned from doing professional work in his field due to an affiliation with the Communist Party.

So Frank, with his career and his lifestream stripped away by McCarthyism, moved to a ranch. He ended up farming cattle for a little while. He taught some high school. And he eventually embarked on a path that no one had previously tread, no one even saw coming.

And what he built out of this exile was the realization that the world needed a museum of human perception to make science accessible and scrutable to every person. And so he began raising the funds to build what would become The Exploratorium, which is a museum where visitors can use their hands and learn that the world’s seemingly mundane materials all around us actually contain real deep and profound magic.

So Frank used his brilliance to make that joy a possibility in discovering tinkering that science offers is contagious, while his brother J. Robert, who followed the highest-achieving path of success laid out for him as structured by the field of physics, who won all of the prizes, found his way into creating the most dangerous weapon of mass destruction ever invented.

I was a fellow at the Exploratorium in 2019, in the before times. And while I was there I thought a lot about these brothers and their wildly diverging fates and really came to thinking of them as representing the two sides of the coin of what we call technology offers us. One is about this like ongoing pursuit of understanding, and the pursuit of curiosity. And the other one is about the seeking of power and destruction.

Since the pandemic hit, many of us I think feel like Frank on the cattle ranch. We’re trapped in exile in our own lives. So I want this talk talk to be an opportunity to think about what the destinations are on these two paths, and perhaps give yourself permission to daydream, and close your eyes, and imagine a more strange and personal destination for yourself.

Jane Jacobs, who wrote my favorite design book of all time, The Death and Life of Great American Cities— I may be the only person who considers this a design book, but she makes this point beautifully that the world is full of all of this false order and all of this false structure that doesn’t necessarily deserve our respect. And I think that the moment we truly realize this, like the moment we internalize this, is the moment we become empowered as creative people, listening to our own rather than those externally-imposed imperatives and structures.

This frees us from our fixed assumption about what the world needs, what we should be making, what has to be done, what materials we’re allowed to work with, and allows us to go straight for pushing at the bounds of what’s possible and just explore. And I’ve found design is really the perfect tool and the perfect methodology to do this, because design doesn’t care what is supposed to work. Design doesn’t care what you’re supposed to do. Design only cares about what you can make. What can actually be prototyped. What type of graphic design actually communicates to the person looking at it. Everything is about tests and proofs of those tests.

And it doesn’t require fancy tools. Like in my work I found that even the most ubiquitous low-tech materials like…cheap materials like paper and cheap plastic are capable of revealing new, amazing facets of our reality. Cheap materials in particular, they scale dramatically. So the same principles that work in tiny hand-held experiences can be scaled up to a level of spacecraft, which is something we’ll get into a little bit later.

This is an animation that I made out of a puddle of water of Muybridge’s running horse. I made it by cutting a stencil with my Craft ROBO vinyl cutter, which I might show you later.

And then I used a hydrophobic coating on the glass to corral water into these shapes to make each one of these individual frames.

When experimenting and trying to figure out what projects to develop, I often think about Mary Oliver’s very simple instructions for living a life that we should pay attention and be astonished, and then tell about it. And try to just remain pretty honest with myself and letting my astonishment lead me, and hope that others are charmed by it as well.

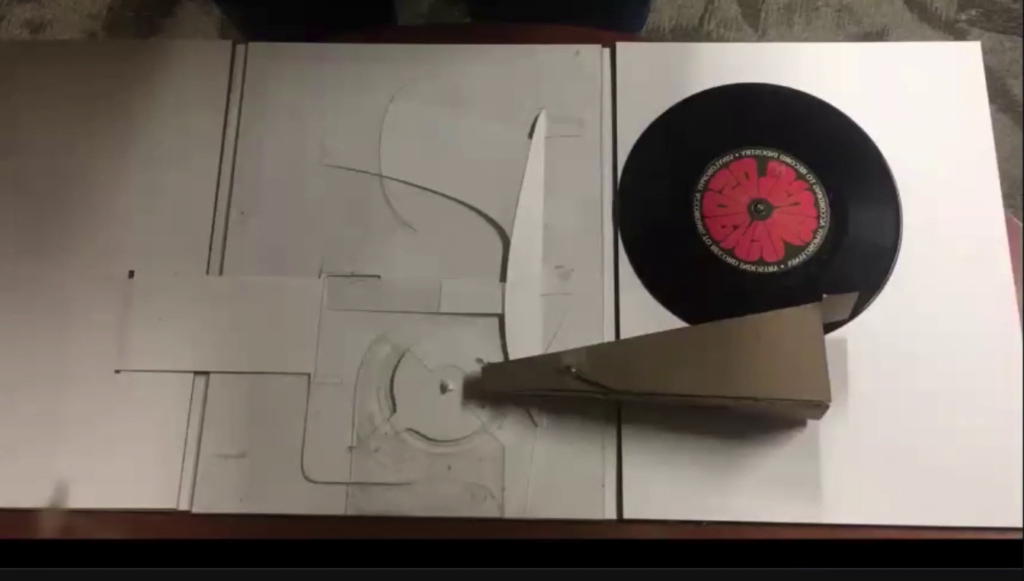

This project really represents when I first got hooked on my own astonishment. So this is a wedding invitation that I did about a decade ago for my friend, open source advocate Karen Sandler and her husband Mike. And it’s based on this idea that like, you can make a record player from almost nothing. That you can roll up a cone of paper, tape a needle to it, and that’s enough to amplify that sound, those vibrations, from those grooves into audibility.

So this was a really fun A/B testing process, because I bought acupuncture needles, I bought sewing needles, I bought all kinds of different papers to try to test out the parameters of what is going to make this little hand-held record player the loudest. And meanwhile Mike and Karen were writing this really adorable song inviting guests to the wedding. And we put it on a flexi disc, which is a totally clear and totally crappy flexible acetate record.

And you can see here that the couple on it, they’re printed in black and all of the color you see is the page beneath. So that way there’s this interplay that when you rotate that clear disk it lines up with the underneath colors, and it completes the couple in all of these disguises. So, turn it 90 degrees and then you get Karen and Mike here playing music together. And another 90 degrees and they’re eating and drinking and being merry. And then finally growing old together.

And the reason that I did this was to A, entice people to actually turn the record. But also so that we’d have a design fallback justification in case the record didn’t actually play. Because even though I had extensively prototyped and A/B tested every single needle and paper, there was always the possibility that like, the one #7 needle I had happened to fit in the groove properly and then the 300 I ordered in bulk were not gonna work. So, always a peril. But it did work, and this is how does. So, the device corrals minute soundwave vibrations:

https://vimeo.com/22306468

Okay. So, you could hear the actual recording versus the original song. And it was the funniest thing because I feel like all of my friends are the type of people who sit around and fuss over like, record fidelity and complain about how some obscure album isn’t in Bandcamp or whatever. But people really seemed to like this thing that did not sound good, did not work well, only had one song. In fact it was so popular it went viral. And I’m stuck with this like, really weird question but it turned out to be a very generative question of like, isn’t the whole purpose of high-tech things…don’t we want these technologies to function well?

And you know, I thought about this. Like, why is it that these lo-fi, glued and taped-together things are so appealing and and endearing in a world where we can make anything we want to happen on a screen happen. And I eventually realized, after just a lot of reading, that there’s this weird dimension in our relationship with our things that modern tech just hasn’t really provided or solved yet.

Modern tech gives us whatever we want. It’s like winning at this game of wish fulfillment. It’s kind of its whole deal. But what it doesn’t do in its black box-ness is make the world legible to us in human terms in the way that we connect to the universe.

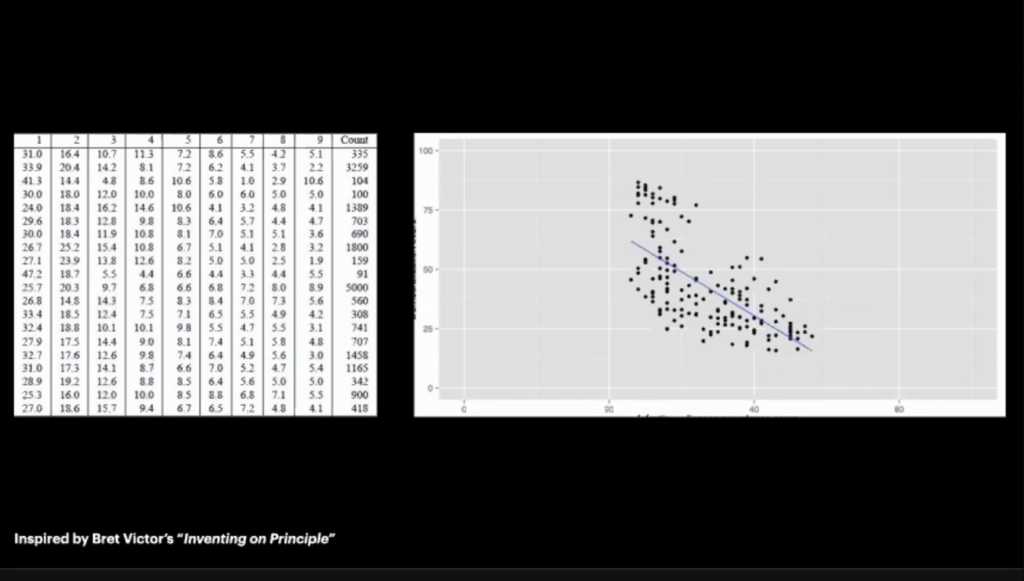

Bret Victor writes about how the scatter plot graph was actually a really important human invention because it was able to make information bioavailable to human perception. This is just a little demonstration of that. If you look at the numbers on the left in the spreadsheet, it’s really hard for your brain to parse that. This is exactly how a computer wants those numbers, but as humans it’s more difficult to read. But as soon as you take those numbers and put them on a map, it opens them up to our spatial reasoning and sort of like touchy-feely perception that we’ve honed as a superpower over thousands of years, just from navigating the world spatially. So our more tangible reasoning skills immediately flag like, alright what’s the outlier? You can find the high point, the low point. You can see the pattern, the spread. You can see where most of them are concentrated. You can immediately start reading this data that was completely obscured to your brain before.

And so I started thinking that you know, we really intellectually think and interact and intuit a lot about the world through out bodies, and through touch, through friction and resistance, much more than anyone talks about. It’d kind of odd and, you know, oftentimes awkward to talk about sensory experience. When I was studying art history, we oftentimes called describing a painting—you’d be like oh, that’s like dancing about architecture. Which is why I think it’s not done as much.

https://vimeo.com/72393668

The nervous system doesn’t end with the brain alone. It extends all the way to the skin. So, everything we know as humans is an event on the skin, whether it’s light hitting our retinas, or sound vibrating our eardrums, or molecules hitting our taste buds. We are simply hard-wired as people to have these very deep and rich intellectual and philosophical exchanges with how we interface with the physical world.

So since we’re physical beings, analog tech was always in the background, secretly…you know, in addition to doing the wish fulfillment thing, it was fulfilling the secondary function of tethering us, us material beings, to the larger universe of material things. So like, spending time fussing with an antenna to try to find a radio station provides a connection point between our bodies and our minds, and this technology that we’re working with.

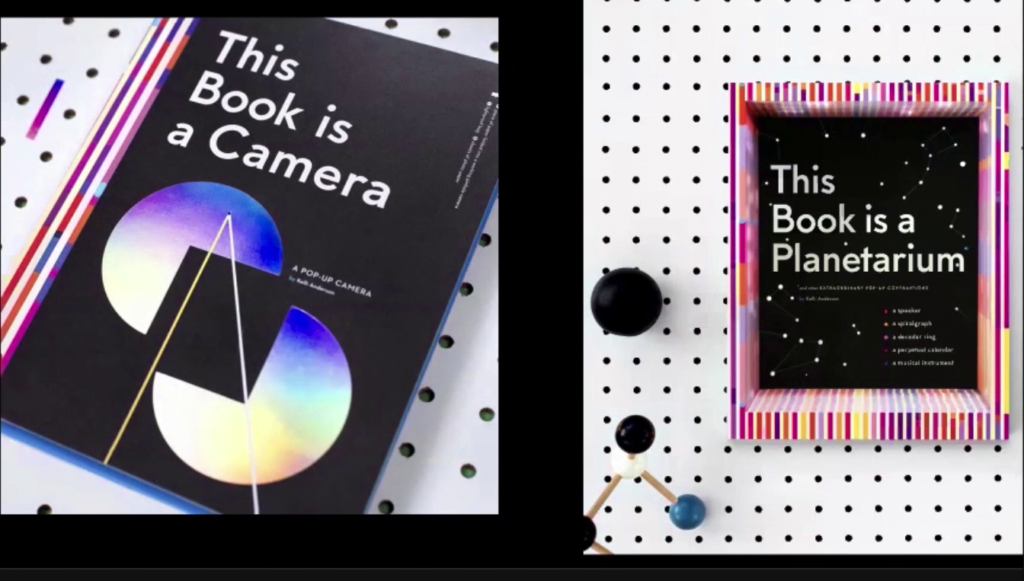

So, knowing that and wanting to introduce for example children who may have grown up with digital devices into the magic of the physical world, I started writing these books that teach through physical interaction and touch, making these humble paper technology things that could function as a direct interface in the wonder of physics. So this first one is called This Book is a Camera.

https://vimeo.com/146785653

And it’s a very literal title. It lets the user/reader interact with light and learn about how light works through using it as a pinhole camera. So you load photo paper into the back of it in the dark. You take a photo. And then you unload it in your bathroom and you can develop it in instant coffee and baking soda and water.

It takes pretty good photos. They’re large format, so they’re like four inches by five inches.

And a year later, this follow-up came out. This was a larger collection of devices that asked my favorite generative question in the world of what can paper do. And answering with six different paper technologies. So people can take their hand and tinker with concepts of time, and concepts of how calendars are organized, concepts of encoding and encryption, play with the directionality of sound waves, play with pitch, play with how computers draw mathematically; a spirograph is basically like an analog version of openFrameworks.

And also how the stars in this skies work. This is another super literal title. There’s a little planetarium inside the book.

Another argument that I want to flag, that the straitjacket of the sort of structured professionalized thinking in tech limits us, is that we tend not to draw upon the full toolkit of human discovery because the line between craft and tech is oftentimes so rigid. Which has more to do I think with the dominance of the Western Industrial Revolution than it does with craft techniques’ ability to produce function. And so we might consider looking to non-Western cultures for their design wisdom when faced with these high-tech challenges.

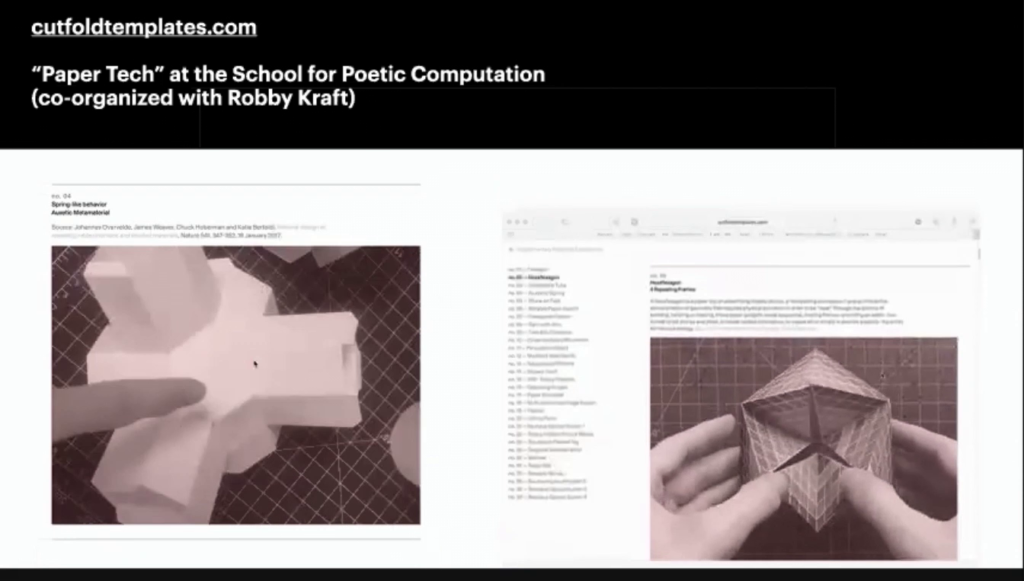

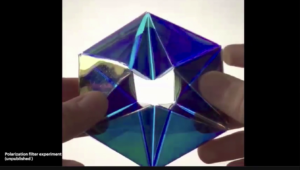

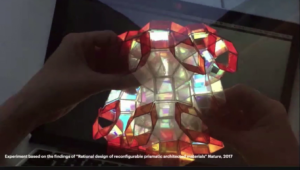

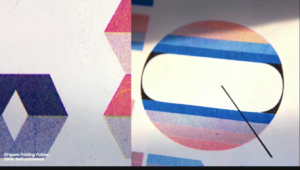

For example, these technical origami patterns are being used to solve problems in spacecraft design over at JPL NASA. What I’m showing you is a set of risograph origami tessellations that talk about paper as tech and explain that paper has a material memory that we can program by folding. Once you fold a piece of paper, it never forgets where that line is and it always wants to redirect pressure. This is a series of different paper folding activities that provide different choreographies of motion redirecting through these complex networks of folds.

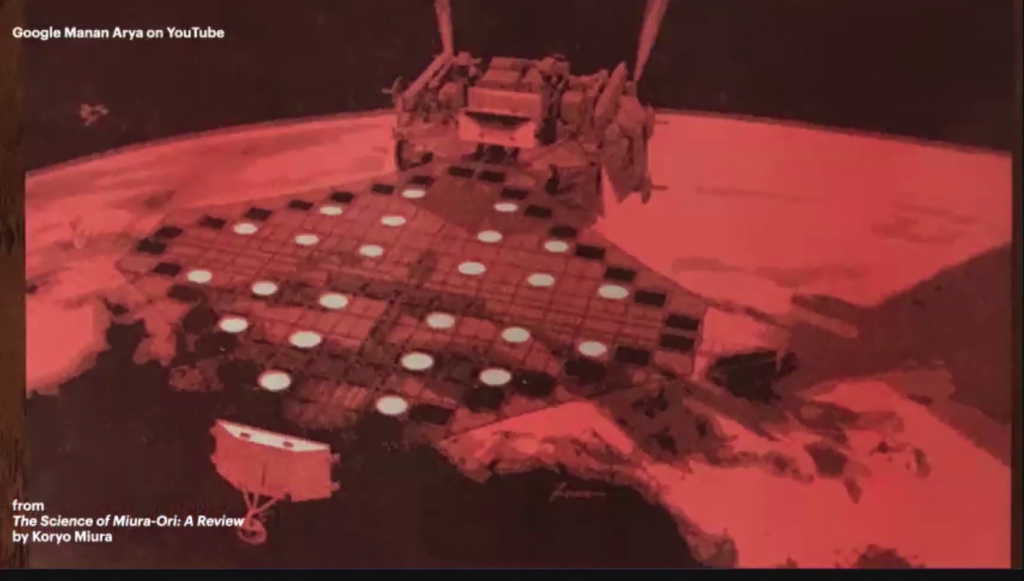

This one is my favorite. This is the Miura-Ori fold, which converts an inert sheet of paper into a multi-directional paper spring. And this form was developed by Koryo Miura, who is an astrophysicist who drew from the ancient tradition of origami— So he envisioned the Miura-Ori fold as a solution to of all things, a satellite design problem.

This [1995] Space Flyer specifically. If you Google Manan Arya—I have his name typed onto this slide—on YouTube, you can learn more about this thing. It needed an array of shifting solar panels to track with the sun using minimal energy. So that’s how origami came in to solve this problem.

Beyond paper, “Kat-Ku Kia‘i Mauna” [@awahihte on Twitter] writes that she hates the term “basket weaving.” It’s so often used as a shorthand for something irrelevant and useless. That there’s so much math and plant care, planning, symbolism, story, and skill that goes into basket weaving that it’s settler arrogance to dismiss these knowledge systems. There’s a whole lot of knowledge systems that we don’t think to tap into because they come out of these different craft traditions.

So, in my work there has been this trend of scaling down these large-scale concepts into hand-held tiny things. But now that we are in 2021 I feel like all of the projects I’m working on this year are…ballooning sort of out of control. So I’m just going to show you a little bit about what’s on my desk right now.

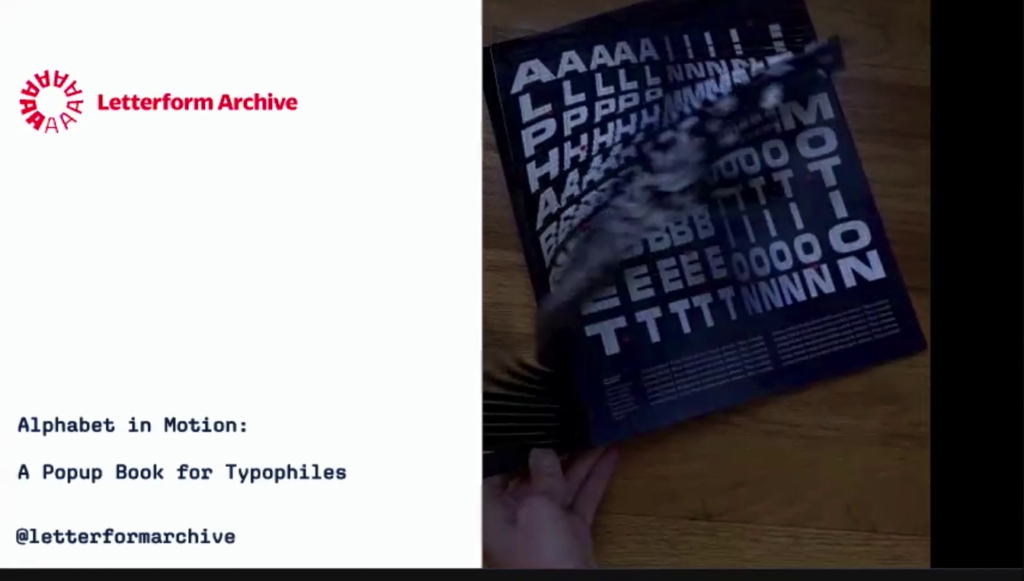

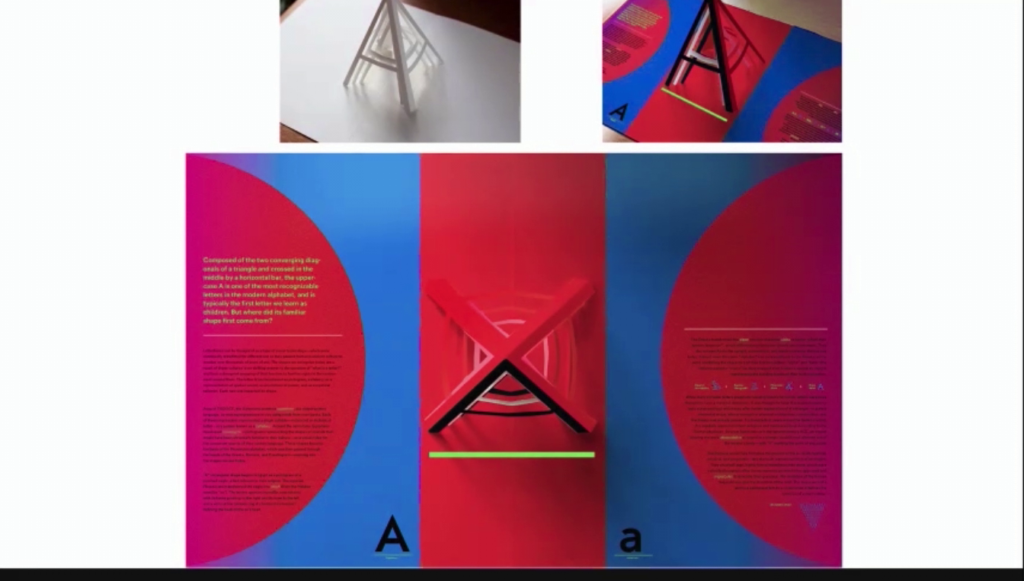

So this year I am working with Letterform Archive’s publishing program, and I’m making a book that demonstrates typographic concepts with seventeen different paper gadgets. So…yeah. I made a one-page pop-up book, a six-page pop-up book, and now we’re like, jumping to seventeen pages. But all the prototypes are at the printer, and I’m writing the essays, doing the graphic design now. This is a rough prototype of the cover that I’m showing you.

And with this book, I’m exploring these mechanical idioms to explain the story of type technology, which progresses from the mechanical to this flat digital experience where all type is pretty much on screens now.

And the book largely focuses on this transitional moment from metal type to screen technology, so I’m employing this neon sort of RGB aesthetic to design. This is the letter A page.

This is a rejected prototype, but it sort of sums up what I’m doing here. So, here I was trying to a create physical analog for that expansive feeling of variable or parametric type on sliders. You could hold this and all of these letters turn into like their extended form as you go ahead and pull that tab.

The essays focus on the notion that type is an impossibly microcosmic representation of culture that’s ever-changing. And that the changes in the world, and the changes that we see throughout history and technology are also perceptible if you look at type. It just happens in this teeny tiny subtle scale.

So I’m hoping the book answers questions like you know, when I see warped and distorted and projected type, like you do in film noir posters for example, why does it feel like psychedelia, by tracing its aesthetic origin back to the source. So, this is the spread for the letter J, and it’s all about the aesthetics of light projection, of projecting a two-dimensional shape on to three-dimensional environments and how that warps and manipulates type.

So it’s an experience you can have in your bathroom, but it has the intention of conjuring up references to like, The Joshua Light Show, Andy Warhol’s Plastic Exploding thing, inevitable…Brion Gysin’s meditation device.

And also ties into the basic mechanics of photolettering, which rose during this time period as an alternative to metal type. This method allowed for a ton of experimentation, which is why we see all of this warping and distorted shapes in graphic design of this time. It also allowed typefaces to be developed faster because they didn’t have to be cast in lead.

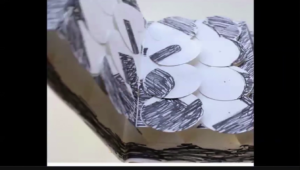

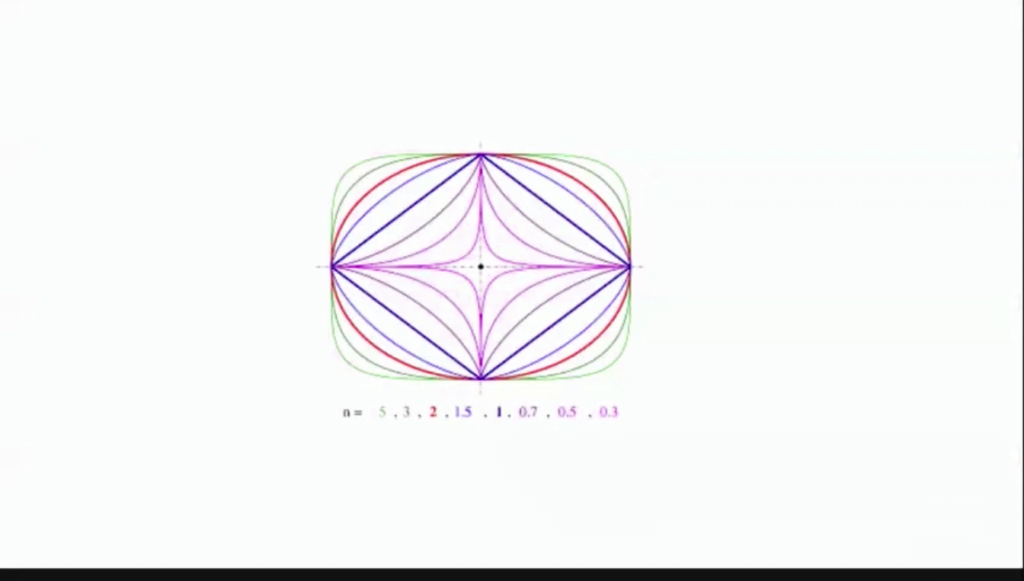

Another 60s zeitgeist actually is why do certain typefaces like Eurostile—I never pronounce it right. This is a hand-drawn version of [indistinct]. Why do these shapes always feel so mod? So this is a prototype for the letter R page. It’s created out of sixteen different spinning disks.

The animation of these disks works simply through V‑folds, which is kind of the simplest form in paper engineering. Paper engineering’s all about taking one basic form and sort of like fractaling it out in a crazy way. So each one rotates on these hooks and then the circles rotate [inaudible].

But the answer to why it feels so mod, like [Anagrama?] on the dashboard in 2001: A Space Odyssey is because all of these letterforms, these wide, extended letterforms from the 60s are built upon a different shape than other letters have been.

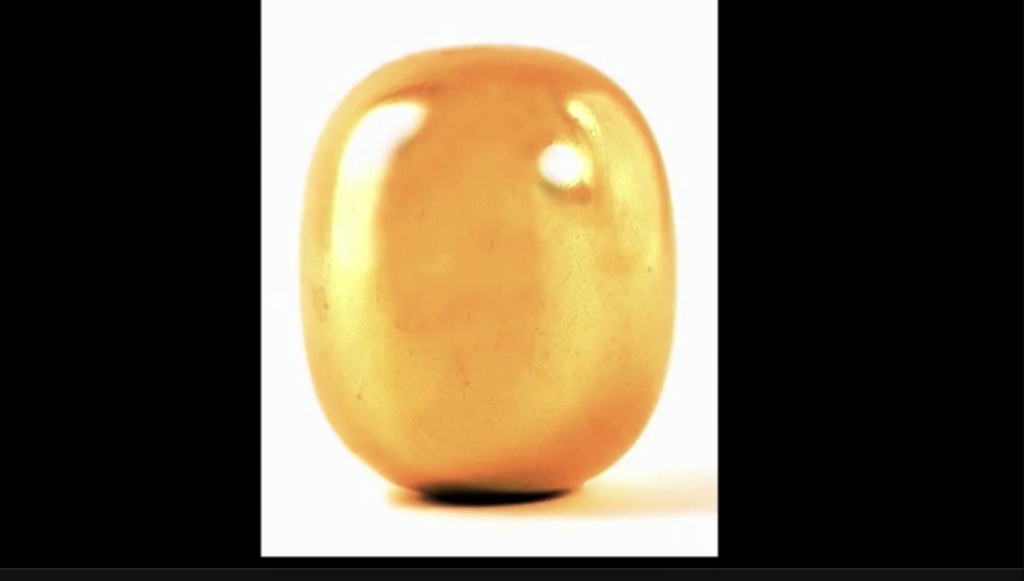

They’re built upon the shape of a superellipse. Which is a shape that came on pretty strong in the 60s, and then went out of vogue really quickly. Sort of forever to be associated with this moment in time. The superellipse is a post-World War II invention which is not quite organic, not quite geometric. There’s a certain left of technological precision and industrial precision required to manufacture the shape.

It was identified and named by a Danish poet and recreational mathematician, Piet Hein for his 1959 proposal for a redesign of a roundabout in Stockholm. He explained the shape’s aesthetic presence as a compromise. That in the whole pattern of civilization, there have been these two tendencies, one toward straight lines and one toward circular lines. And each one has its drawbacks. And so he invented the shape called the superellipse to solve this.

And it made its way, as industry was able to produce this precision shape, onto all of the industrial design of the time. Onto TV screens, the shape of plates.

He even made this like…this is called a superegg. It’s a toy. And the two options are it can sit upright, or it can roll on its side.

So, yeah. This also made its way into typography of the time.

I’m running out of time so I’m going to be fast.

So…I’ve got to tell you this story. So in 1968, when the Vietnam War negotiations were happening in Paris they couldn’t agree on the shape of the table. Should they have a rectangular table, should they have a circular table. And ultimately they made the negotiation table in the shape of a superellipse as a compromise between these two opposing geometric tendencies.

So yeah. That’s why those shapes feel mod. So I’m just gonna gratuitously scroll past a couple other prototypes. This is the mechanical O. I was gonna talk all about mechanical signage in Las Vegas.

This one is all about Wim Crouwel, and I just put my URL in there in case you want to learn more about this book, since I’m kind of speeding fast.

So these are all prototypes I just made on my desk with like spray paint and tape and glue and paper.

And I’m just gonna show you two more things really quickly.

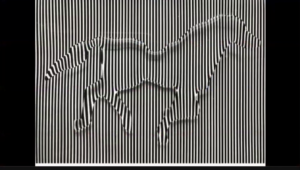

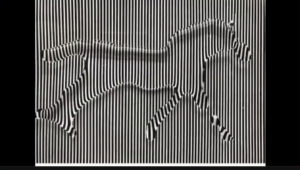

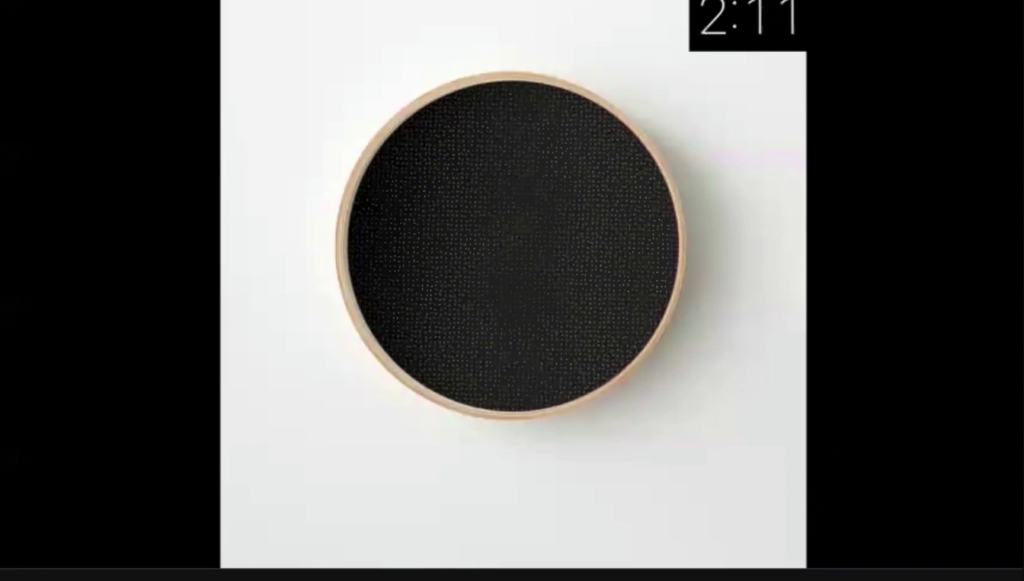

Another project that I’m scaling up. I’ve been researching this concept of moire magnification, where you take a screen with apertures in one period and lay it over a printed grid of dots with the same period, and it creates this magnification effect.

So I’ve been playing with this at a small scale in books, but I’m scaling it up this year. I’ve started to work on prototyping a clock based on this concept, where time comes and goes. So this is a clock with a whole bunch of little tiny 2s and 3s that scales as you rotate it.

I’ve also been making a more complex record player as part of a larger book about sound in the same vein as the other two books that I’ve made.

And then this, I just wanted to show you…I don’t think we have time. But in case we have time to walk over and see the rest of my studio. This is the most recent project I just finished. This is a stop-motion I made for the New Public festival.

https://vimeo.com/498429105

So as you can see, I’m really obsessed with this idea of like, craft materials being physically programmed. So this N was purpose-built designed to turn into this P. When I pulled on a string, it cascaded into all these little geometric shapes rolling up on each other. So I love that. I feel like it is sort of a function that my eyes can follow, and I think it helps me connect my human senses. And I think about sort of like the enduring legacy and feel, as well as the experimentation that’s offered by these different craft methods.

So yeah. I think I went a little bit over, Golan. I’m so sorry, but that’s what I have.

Golan Levin: Thank you, so much Kelli for gifting us with this view onto your work.

We are a little bit over time and there’s been a great request coming from the Discord where all the chat’s happening, which is rather than having you answer with words, I wonder if you could just take your camera over and just give us a glimpse that we can consume with our eyes, if we could see your desk or your studio. There’s a lot of curiosity to sort of see the space you work in. Which is something that we don’t get in the normal kind of talk.

Kelli Anderson: Yeah. Totally. So everything’s a mess, and it always is, but this is my very long desk. I made it out of IKEA cabinets. And so there’s a lot of storage there. I cut all of my paper stuff and all of the sheet plastic on this machine, which is called a Craft ROBO. It’s a vinyl cutter. There’s also one called a Cricut. There’s also a Silhouette.

And this is my set, which is kind of destroyed right now. But that’s how I made the New Public thing. It’s basically all of these little geometric shapes, and then there’s strings that come down. I couldn’t get it in one take. It was like sixty takes. But that’s what computers are for.

So yeah. I try to do the things that computers do well on a computer, and then do the things that computers don’t do well like shadow and texture and little physical sounds and stuff, all of that physically.

This is a random door I have with the entire contents of my ABC pop-up book taped to it. So that’s how I know what I’m gonna write about and what the pop-ups are.

And then in here, this is kinda like my garage kind of. Like I have a letterpress. I have storage for printed things. I recently got—this is my favorite thing in the world right now. This is a paper drill. So I can make little notebooks and stuff.

So yeah, that’s pretty much it. I’ve been here like twelve years, and so everything you’ve seen me make has happened here and I never leave my house, even before the pandemic.

Levin: Kelli, thank you so much for sharing with us.