Golan Levin: Welcome back everyone, to the final presentation of our Friday afternoon session. There is of course a Friday evening session, which will start at 5:00 o’clock, I believe. But for now, it’s our great pleasure to introduce Imin Yeh.

Imin Yeh is an interdisciplinary and project-based artist working in sculpture, installation, and participatory events, especially involving the innovative use of paper and printing. Imin is my colleague here at Carnegie Mellon, and she is currently an Assistant Professor at Carnegie Mellon University School of Art. Everyone, Imin Yeh.

Imin Yeh: Hi, thank you so much. So my name is Imin. I consider myself a project-based artist. I get sort of really obsessed with making these very one-to-one paper replicas of different objects I find in the world. And in this presentation I’m gonna talk about a couple larger projects, as well as to give some insight about what it is that draws me to whatever it is that I’m making a replica of.

And so why paper? I think of paper as like that OG, like original technology that changed the world. So along with the development of the written language, paper, printing—and printing is my area of focus within CMU, those things were about humans wanting to leave a record and leave their stories and spread it to as many people as possible. And there’s something about that that’s unique to our species. A desire to communicate with far beyond the immediate people in our vicinity. And so that is one of the main reasons why I’m so in love with paper and printing, this humble material that we now think of as…nothing. You know, a scrap piece of paper—we don’t even need it; we’re moving to a post-paper world—is also the paper that is like the oldest record and the oldest archive of the entire sort of human story.

So all of my sculptures are unified by that they’re almost…you know 99.9% just paper, with different methods of printing, and are all handmade. And so the smallest sculpture that I’ve ever made is the stinkbug. And I think a lot about scale, and how the smallest thing can take up space. So this was a copy of a stinkbug that actually was in a white installation of mine. And I had to make a copy of it, and it actually traveled to the Smithsonian Natural History Museum in Washington DC, where I coerced my mother who’s a volunteer there to put it in the collections.

And the largest sculpture I’ve ever made is the seventeen-foot-long paper black I‑beam that matched another I‑beam that was in a gallery space here in Pittsburgh. And even though this is the largest sculpture I’ve ever made, and that these I‑beams actually function in the space to hold it up, nobody could see it. And so I spent the entire art opening protecting the I‑beam from being smashed by all of the visitors. And so that’s sort of the the range of objects that I am in love with.

I think maybe a sculpture that best illustrates this idea of humble things taking up bigger space and bigger value in the world is something like this. This is the Pittsburgh Parking Chair, an idea that a chair if put in a certain space can take the importance of a car which has a clear value and a clear usage factor. And so I am really interested in the idea of usage and how value is invested by like, the story behind the object or the labor in making the object.

Other things that really sort of illustrate that to me are electrical conduits and wires around buildings and how people will paint them to hide them. That they have such a use but they’re not valued sort of like aesthetically in the space. So I love that.

This is at the Asian Art Museum. They have armatures protecting precious ceramic work—and someone’s job is to paint them so they disappear and that you can’t see them—from earthquakes, and I love that function, right. Like the function of something versus the lack of function of art is interesting. I wish my art was as good as this painted armature.

When I look at art and photos of art in museums or on Instagram on people’s web sites, I can’t help but notice that sharing the space often are outlets. And this idea that again the outlet is so ubiquitous and so necessary. It’s part of building code, it’s the only way that we can charge things and light things up and have a space be useful. And it’s always sort of alongside these precious artworks that don’t have a utility value other than like, catalysts to thinking, or sort of formal objects to look at. And so once you start seeing the outlets you can’t stop seeing them.

An older work is Paper Phone Jack: A Sculpture For Not Working, which is a downloadable project. I have a lot of downloadable practice, where people can download and make their own paper sculptures. So I love the phone jack in that it was a technology that was in every single house and every building and now is rarely used. And so there’s these like vestigial objects in walls.

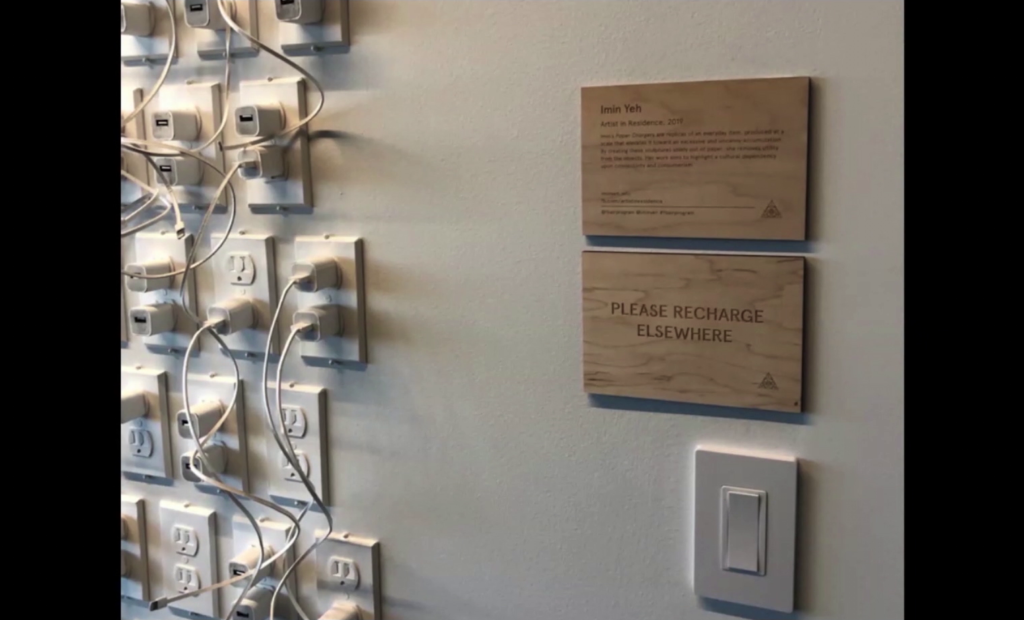

And my love of outlets eventually bled into this idea that everyone needs an iPhone charger and that we’re so sort of connected to these devices and we need to be charged, which built up into this large installation of about 300 paper outlets and iPhone chargers. And my big exciting news with this is that this is actually a commission for the Facebook Oculus building here in Pittsburgh. And so this building that is made to sort of…a think tank of creating the cutting edge sort of technology on virtual reality and augmented reality is actually hosting all of these sort of useless outlets.

And then finally, the biggest exciting point of that is that they had to put a sign up on the space to urge their staff to not charge anywhere near the art. So I love the usefulness, becoming unuseful, becoming valuable because of the labor becoming art.

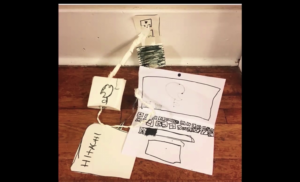

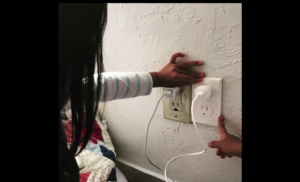

And of course a friend of mine’s daughter loved the sculpture and decided to make this paper laptop, outlet, and external hard drive as a gift. And we ended up doing a trade, where I traded her one of the sculptures. And that is sort of my last point with paper, that it is the material of childhood. That children just make what they want. And that imagination and play is so exciting.

So one of the first works I ever did in this way of thinking is a make-your-own downloadable paper mahjong set. So you can build this set entirely for free if you download the PDF. And commit yourself to thirty or forty hours of making. The idea being that the value is entirely in your labor.

And this project is over a decade old, but just a few months ago a young man in India actually emailed me during quarantine. He saw the paper mahjong project online, and he has been really interested in learning how to play mahjong, unable to find it in his town, found my web site, found the PDF download it, and made it. And sent me this email and sent me all these pictures of how this PDF became an actual set in his home.

And so this is his built set. And that’s him. So that was a little bit of magic of this idea of play and exchange, and just putting these files out there into the world.

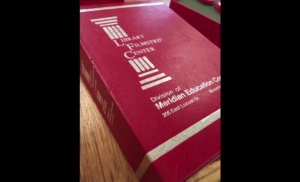

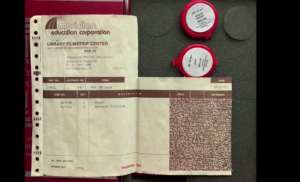

Another recent project is at CMU in the storage closet in the printmaking area I found this filmstrip box set. Now this box set is two filmstrips and two cassettes about paper and printing. It was published in 1983. The university bought in 1987. And they spent almost $200 on this box set and it was never used. I mean, the cassettes were wound so tight, the film canisters weren’t open. It even included the original receipt. And I was so tickled by this because I love archive history, obviously I love books, and I love that moment where in technology where they thought like, the filmstrip is gonna be this innovative way where we can talk about paper and printing and not in this boring book way but in this exciting like, multimedia way and you had to have all this other equipment to share the information. And so I knew I had to make a paper copy of this, and I got invited to do a residency at Women’s Studio Workshop to produce this into a large-edition artist’s book.

And to do it I used every single tool in the printmaking trade. So there’s silver foil embossing, there’s handmade paper to look like foam that was die-cut on a letterpress, hand-built foam inserts.

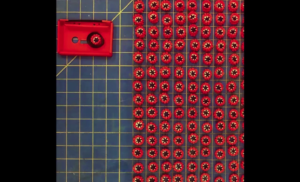

Each cassette was built by hand, screenprinted with the labels.

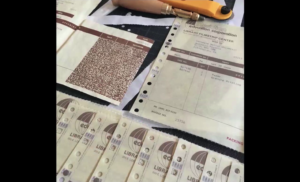

Copies of the film canisters. I had to make a copy of this beautiful receipt. So actually each of the dot matrix paper is like, hand-perforated and the holes are cut.

And this is the final box set. You can see the original on the left and my artist’s book on the right. And because it’s an artist’s book there was a lot of pressure to like, make it actually a book, and so I decided to try to actually glean the information off the original filmstrip.

And to do that, all of these old boom boxes had to be dragged up from the basement of this art center, and huge amounts of double‑D batteries were involved. So we eventually played the tapes and transcribed them. They eBay’d this old film projector in order to project the film, and set up a DSLR camera to document the slides.

And so with the images from the film about paper and the audio from the film on paper, I built it into an artist’s book that basically is just the entire presentation into a book form.

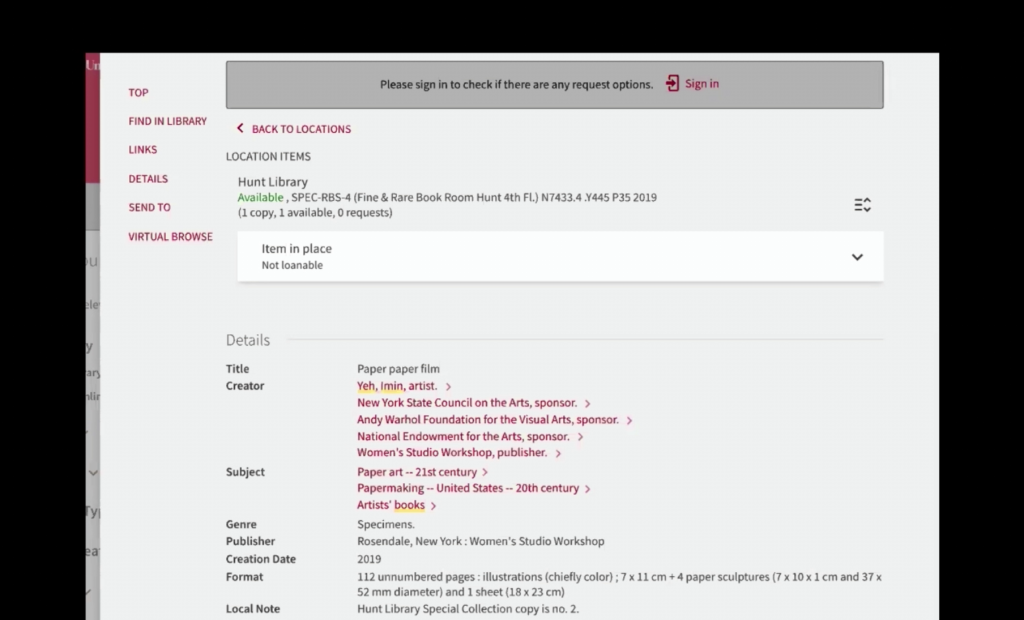

And because this whole thing is an artist’s book, what’s exciting to me is that it’s actually being collected back into libraries and special collections, rare art book rooms. So this is the the search engine at the Hunt Library here at CMU. And I love the idea of these things getting to exist as sculptures to look at and then preserved and protected and cared for as archived special objects that were just discarded and forgotten about.

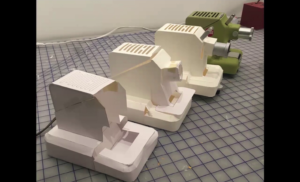

And then of course because this beautiful film projector is so extremely good-looking and I’m very obsessed with the mechanical industrial age of technology, because there were still like knobs and gears and you could still really see how it works, I had to make this out of paper. And so a few shots of my process, which is all just hand-tailored pieces, often using sort of screenprinting for the graphics and text.

Building all the knobs. And the final sculpture. And I do think a lot about as our technology becomes more digital and more nano and micro and how uncomplicated they are as objects, will they make not as interesting of a sculpture. Open-ended question for the discussion.

Okay. So the last project I wanted to share today is a project that was sponsored by the STUDIO here. It’s The Making of the World’s First Paper Facsimile of the World’s Oldest Blue LED.

So I did a residency at the Sarnoff Collection, which is RCA’s corporate archive. And what you’re looking at here is the world’s first blue LED, a prototype made in 1972 by Herbert Paul Maruska. And it was the first time that someone was able to get the light to glow blue. I knew I had to make a copy of this because it was such a handmade prototype.

This is a little picture from the archive, “Will the blue LED ever make Maruska a rich man?” Before this invention could really take off, RCA went bankrupt, closed down, they didn’t continue supporting this invention. And the momentum behind this disappeared. And it wasn’t until the 1990s where a trio of Japanese engineers designed an LED light that would ultimately win them the Noble Nobel Prize in physics just a few years ago. But they all cite Maruska as the original inventor of the blue LED.

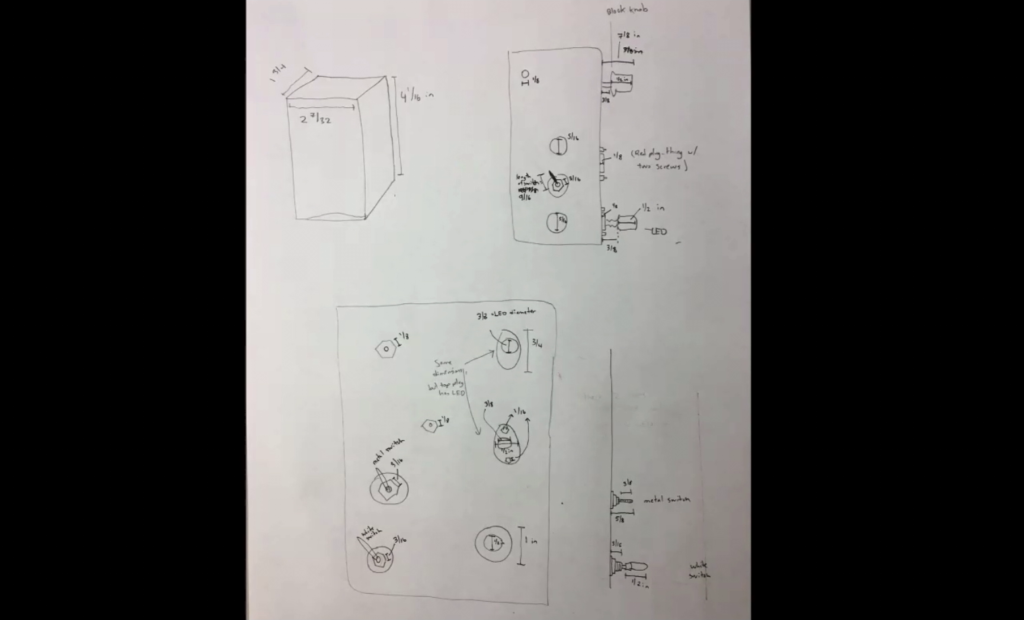

So in order to make this, the curator at the Sarnoff Collection sent me pictures of the machine and also a wonderful drawing of all of the dimensions of the blue LED.

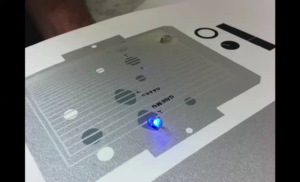

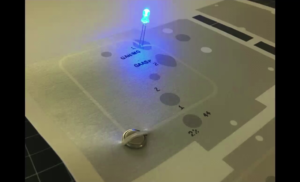

This is my first paper prototype. I got to play with conductive screenprinting inks to see if I could power the light with just a three-volt coin battery. And this was the sort of final prototype that it could power from just a small battery as a portable sculpture.

But I had an interest in building it into a much larger sculpture, one that utilized some programming in order to blink the light in Morse code in order to sort of speak a story, an interest to sort of make sort of a far bigger impact, maybe than this smaller, single sculpture. And with varied results. So here are some pictures of the attempting to make that sculpture.

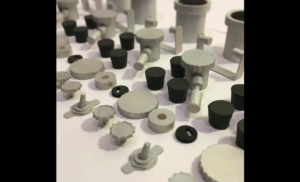

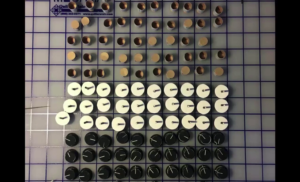

So lots of paper screws, paper knobs, hand-drawn masking tape arrows.

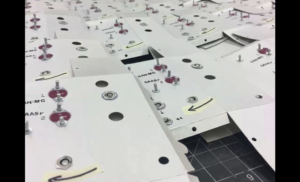

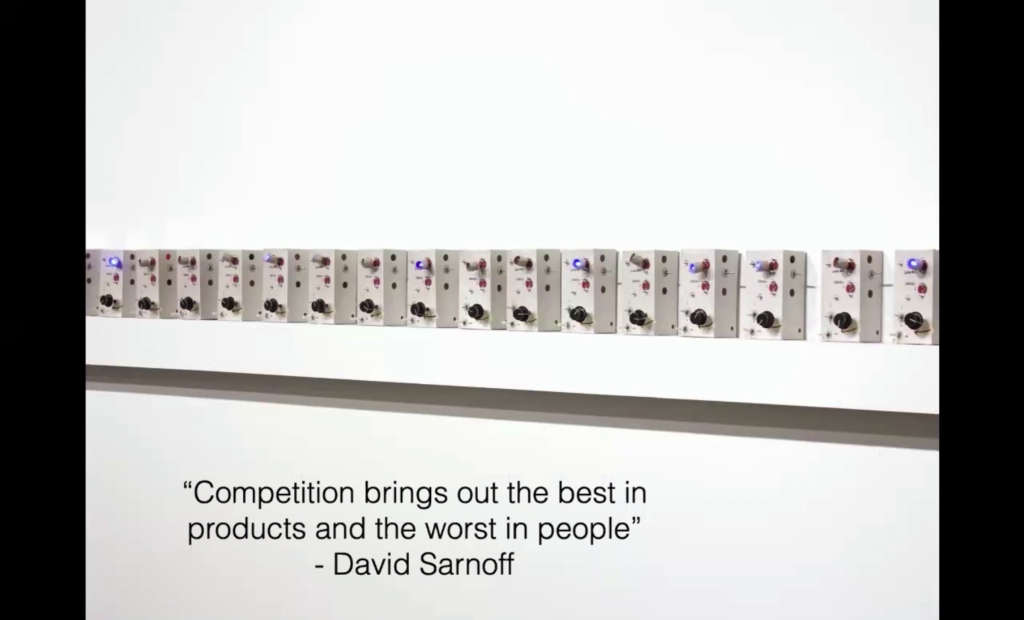

Ultimately building about sixty of these sculptures. In order to make them be programmable with Morse code, I had to hard-wire in these Arduino Nanos to code the lights. Which I’ve never done.

So here’s all of the wired sculptures. To power the Nanos, I needed electricity, which is something that as you know with the outlets I don’t often engage with. And because there was hardwires and electricity, then I needed to build a shelf in order to hide the cords. And I was not very good at soldering so there was a lot of soldering in the gallery.

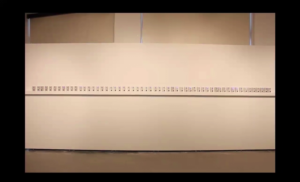

And finally the work…works, and the lights would blink in Morse code. And in order to ship them or carry them I had to build these custom boxes. And finally the final piece in the exhibition.

So what you’re looking at is about sixty copies of the blue LED, each programed to speak one letter in Morse code. And what they spell is a famous quote by David Sarnoff, the chairman of RCA at the time, which was, “Competition brings out the best in products and the worst in people.” And I think so much about that quote in my own practice in that I want to do the opposite. I want to make really bad products that don’t do anything, that don’t have any function, but maybe are the best in the human ability to make by hand or to create. So this is like my anti-quote.

But all this to say all of that work with the soldering and the electricity, I took the original prototype that was just powered by a three-volt battery, brought it back to the museum, placed it on the shelf next to the original blue LED light, and it eventually just lost its juice and together they were just two lights that once shined blue. And I do think in that simple gesture of the one-to-one and just the giving back, the work is at its strongest.

We’re gonna watch a short .

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qHJLG3Wb_Fo

Because I make multiples and because a part of my practice is always about sharing, I ended up sending that light back to Herbert in Florida. And he wrote back “Dear Professor Yeh, what a pleasant surprise the other day when the postman delivered your box. I’m happy to report that the paper replica arrived in perfect condition and now sits on a shelf in my office. It is an exact replica of the original.”

So I think that that idea of a gift, of the one-to-one, of the copy that is worth preserving even though has no more function, is some of the magic in my work. And in that gesture, I always have a gift at the end of my presentation. So a brand new sculpture for everyone here. It’s available in the zine as part of the festival’s downloadable giveaways and also on my web site. This is a paper watch copy of an illustration from a 1981 Byte magazine cover of a future computer wrist computer. And so on the right is the paper sculpture. On the zine and also on my web site you can download the pattern and the bits in order to make the watch. You can see on my web site I have a whole series of downloadable art projects which I would love to share with you all and I always love DM images of sculptures being made.

And then I’m gonna just quickly show you that it’s a real watch in real life. And you can just slap it right there on your wrist and try not to do anything all day. ‘Cause you break it. And that’s it.

Golan Levin: Imin, thank you so much for the present of the downloadable watch that is in our zine. It’s on the cover of our zine and if you folks go to the conference web site under “zine,” you’ll see Imin’s page where you can print it out and cut it, put it together.

Imin, we have a lot of really great questions coming up on deck here. I personally love and really admire how your work is in dialogue with technology and how there’s a kind of alchemical quality to the hand-making of these things. That making something that’s seemingly banal like an electrical outlet or an iPhone charger becomes kind of imbued with something incredibly special because of your labor and it’s suddenly remarkable when you make it by hand as opposed to it being in some factory.

One question is how does making this kind of work affect your own relationship to these pieces of technology that you’re recreating? Like, do you feel like you have a closer relationship to them because you know them so intimately, or is there an element of criticality in remaking them in such a useless way?

Imin Yeh: Yeah. I think a little bit of both. But the big thing with the paper film was everyone’s like, “Did you watch the film?” I’m like I don’t care about the film. You know, I cared about the foam, you know. And this receipt that somehow made it through like, almost forty years. And the same thing with that film projector. I guess I think it’s such a beautiful formal object. And in the paper version that’s a display thing, you know. And so it’s like a fetishizing of the industrial design of it, the history of it.

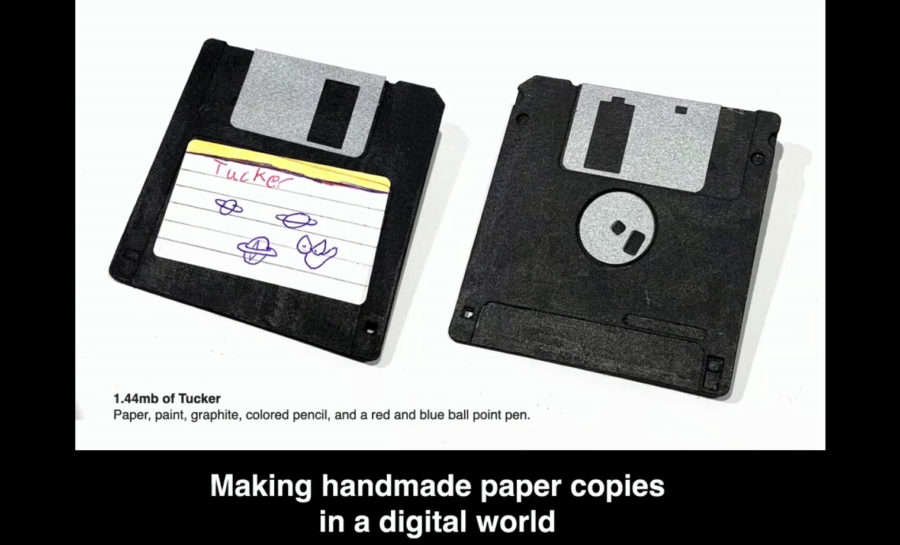

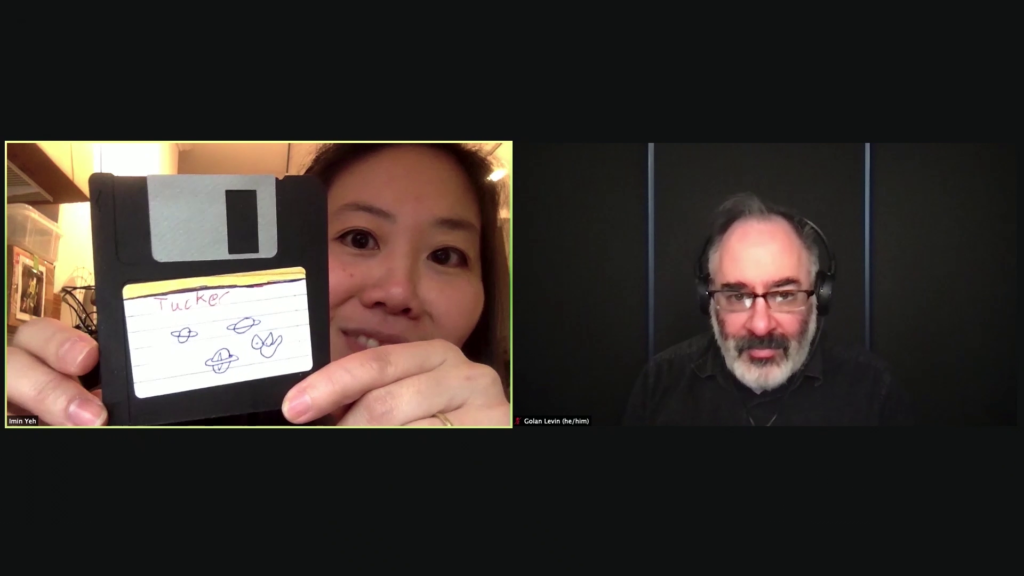

But then once I make the paper copy I almost don’t care about the original, which is like a dangerous thing. But I started my presentation with that 3.5 floppy disk. And then I’ll show it here…

And this is exactly to measurement. But I love this, that like somehow Tucker kept his floppy disk for like thirty-some years and found it in a drawer. And so I wrote to him, I was like, “I’ll make you a paper one as art and then you won’t be a weirdo keeping technology that doesn’t work anymore but you can keep it as a sculpture.” And so I think that kind of gets to the sense of humor with it, or just the love of the object but not the usefulness that it has. I guess.

Levin: Another couple of questions, one of which is could you talk more about the instructable, for lack of a better word, aspect of your work, or the interactive aspect. The publishing of the templates so that people could make it themselves. The sharing the making, what led you to that. I mean, you started making these beautiful things yourself and then suddenly you’re publishing them so that people can make them themselves. What led to that shift and how’s that sort of change your thinking about your practice?

Yeh: Sure. Well actually the mahjong set is basically the first paper sculpture I ever made, and the original idea was always that it was a downloadable version, right. So it was always like yeah you want an original, handmade, authentic, real mahjong set? Then make it yourself. And the practice always existed as a giveaway. And then slowly kind of moved towards…you know, I got five years ago a chance to show that work at the Contemporary Jewish Museum. And then I made a fancy sculpture version. And now it exists where there’s sort of both happening at the same time.

The downloadable PDFs have been this idea that like whatever “job” you work, you can always steal some paper from the printer. And so when I had more boring office jobs I’d like, look up free…you know, there’s so many free craft projects out there and then you could just steal, skim a little paper off the copier and then make work. So I wanted to make stuff so people could like not do work at work. So that’s that that impulse of the free. And I love—because there’s so much fan stuff and there’s a lot of fan art out there and there’s a lot of food objec— I like that these are really kinda useless pattern— I mean like…is someone really gonna make 144 pieces, you know? And one of my favorite sculptures that’s a giveaway is an orange peel, and it’s just this…you know, like an orange peel for the— I think it might be my best work. It’s like, it isn’t a papercraft that you want to make, unless you want to make it. It’s a sculpture. It’s like an artwork, that’s a free papercraft.

Levin: What you’re saying connects to one of the earlier speakers, Max Bittker, who said he makes things for people who are bored at work. And I think Evan Roth is another artist who’s talked about the sort of bored-at-work audience.

The last question is, is there a machine you’d like to make in paper that you haven’t made yet? I know that the wristwatch was one. But do you have one that you’re sort of like…you’re plotting because it’s even more preposterous?

Yeh: There’s so many. I got a tour of the server at the Carnegie Museum, like the basement server. I’d love to do like… Those things are so beautiful with all the crazy cords and lights, and so I would just throw it out there that like that— I’d love…the iPhone thing was this impulse of scale, right. Like an everyday little thing at a scale that was so sort of…formal in its line and its shaped and its shadow. And there’s something about that in like the hidden technology that makes all of the stuff look virtual and wireless and free. So that’s like a dream thing. It’s endless, you know. All of these things are just like…I’m building up my repertoire of buttons and knobs and cords. So I’m just more in shape for that opportunity.

Levin: For when you get the big commission to reproduce a server rack with all those wires coming out.

With that I need to conclude this talk, and I’m just gonna give a quick little note to the audience following about what’s happening this afternoon. At five o’clock, Leah Buechley and Nani Chacon will be presenting. The presentation after that will be at six o’clock. If you didn’t can’t it earlier, unfortunately Olivia McKayla Ross has had to cancel. Something’s pulled her away. But we’ll see you at five o’clock for Leah Buechley and Nanibah Chacon.

And Imin I want to thank you again so much and for all the speakers who were in this session, Ari Melenciano and Sarah Rosalena Brady, thanks everyone and we’ll see you at five.