Golan Levin: Welcome back everyone. My name’s Golan Levin, professor of art at Carnegie Mellon and director of the Art && Code festival. And this is our final session of Art && Code: Homemade: Digital Tools and Crafty Approaches. I’m thrilled to welcome you to the beginning of our evening session. We have four presentations this evening. At 5:00 o’clock, presently, we have ann haeyoung, then Dr. Vernelle A.A. Noel at 5:30 Eastern time, then Hannah Epstein at 6:00 o’clock, and then Kelli Anderson at 6:30 PM Eastern time are the four presentations that round out and conclude Art && Code: Homemade.

It’s now my pleasure to introduce you to ann haeyoung. She is an artist based in Los Angeles and uses video and sculpture to examine questions around technology, identity, and labor. She’s currently an MFA student at UCLA. ann haeyoung.

ann haeyoung: Hi everyone. Thank you so much. Thank you all so much for being here. I’m really excited to be speaking to you and to be here at Art && Code. I hope you’ve enjoyed the talks that we’ve been seeing so far. Really inspiring stuff, so exciting. And thank you to Golan and the Art && Code team, to Lea, Madeline, Claire, Bill and Lisa for having me here and for organizing such a great conference to kick off the new year. It’s been a pretty wild ride already.

And I wanna begin also by acknowledging the Tongva people, on whose unceded lands I am currently living and making. And the Tongva people, for those who don’t know, are the original stewards of the land that many of us may know now as Los Angeles.

So, my name is ann haeyoung. I use she/her/hers pronouns. I’m gonna start screen sharing as well.

I’m an artist, and a technologist, and as Golan mentioned I’m in my first year of an MFA at UCLA. So this is actually the first time I’ve described myself as a technologist. I usually say tech worker although I am not working in the tech industry currently. So I’m still kind of like working through the labels that I want to use, but perhaps that is a good introduction to some of what I’m planning to share with you today. Which is basically what is technology and by extension code, and what is my interest in it.

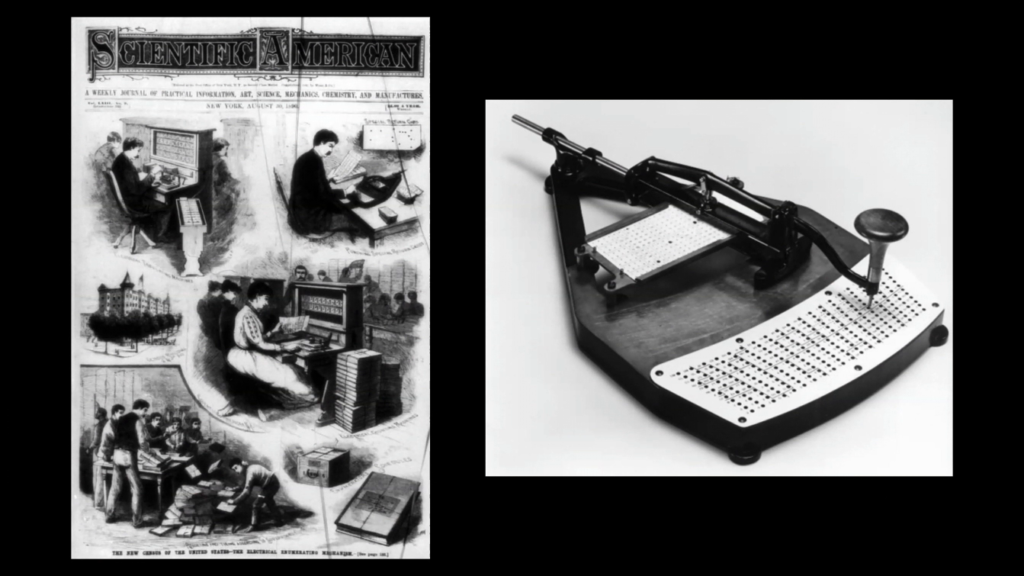

So I think technology, and code as a subset of technology is best thought of as a physical manifestation of our social and cultural values. So in our society, we create technology as a means to control nature and/or human relationships, and as a way to reinforce dominant power structures. For example, early computers were tools of categorization and control. So a key impetus for the first electronic tabulator, which you see here, was the 1890 US Census. So the previous 1880 Census had taken eight years to count by hand. And so a census employee named Herman Hollerith created an automatic counting machine, which is what’s pictured. So the desire for this machine and the creation of this machine followed from the desire to reduce people to data points as a way to allocate government representatives and resources and to be able to do that quickly. So it’s the social and political values which were the driving force behind early computer design and creation. And this same logic applies to even the most cutting-edge AI we create today.

And what is my relationship to technology? So prior to grad school, I was working in the tech industry. I was at Google for a while, and and then at an AI infrastructure startup. And I worked in program and product management. And I do sometimes use code and electronics and AI more directly in my work, but I try to use them pretty minimally, and maybe the reasons for that will become clear. And I like making things in low-tech ways. And I think today I’m only going to be showing the video work that I’m making.

So maybe you could tell from my definition about what I think technology is that my interest in technology is in the systems that we erect around the creation and dissemination of technology on a large scale, rather than focusing on using a particular type of technology. So part of those systems and what I want to focus on today is the physical space in which we make technology, and the people who are making tech. So the workers who write the code, who make the designs, who assemble the machines. And places people tech; these come together in factories of course, but also in offices, which is what I’m going to start with.

So I wanted to show you all a few videos from my office sketch series and this screenshots of some of those. And even though these were made in 2019 and obviously not in the home, I think they’re an example of how I found space for creativity where I was, and an illustration of how important place is to my work.

So I felt really stuck at this office. I was taking weekends or a few days off here and there to work on art projects. And it felt really disjointed. So it was difficult for me to be going into work every day and you know, smiling, biting my tongue, and then going home and feeling like I was being someone else. Especially because my work is extremely critical of the tech industry. So I guess to deal with that, I started looking more closely at the objects and the topography of this place where I was spending a huge chunk of my time. And I started to see this place as a collaborator in my artmaking. And as I started thinking more about this space that I was occupying, I started really getting interested in the office and particularly the tech office as a tool of surveillance and social control.

So this is from social theorist George Lipsitz from his book How Racism Takes Place. And in it he describes something called the white spatial imaginary. So the white spatial imaginary has cultural as well as social consequences. It structures feelings as well as social institutions. The white special imaginary idealizes ‘pure’ and homogeneous spaces, controlled environments, and predictable patterns of design and behavior.

So think about that in relationship to tech. And he’s talking about the space of the suburbs a lot when he’s like— So the white spacial imaginary is not a particular place, but he’s relating it to the space of the suburbs. But I think a lot of what he’s talking about is applicable to corporate tech offices. And so these spaces are really intended for and built for straight white man, and everyone who falls outside of those parameters, who’s not pure and homogeneous, kind of feels that disconnect that this is not a space that’s meant for them. Or us.

And I think it’s impossible for us not to internalize the messaging of a place when we’re spending a lot of time in that place. And once we internalize this messaging, that’s then going to become expressed in the work that we make while we’re in that place. And so another way of saying this is I believe office spaces and tech office space is reinforced white supremacist and capitalist ideas of power and human relationships, and that inevitably finds its way into the technology we make when we’re in those spaces.

So, just kind of switching gears and showing some of the videos that I was making kind of reacting to these ideas and my relationship to these spaces and my feelings of disconnect in them. I wanted to start with this video which is called Conference Call. These don’t have the most original names.

https://vimeo.com/412606835

So for anyone who’s ever worked in an office or sat through a conference call, perhaps this feeling will be familiar to you. But sometimes it felt like I was dissociating from my body. I knew I was sitting there, and there was all this tech jargon coming out of my mouth, but my head was completely somewhere else. And I wasn’t phasing out, because I was the one talking. But it was like I was watching somebody else using my body and talking through my mouth. So this is kind of expressing some of those feelings. And something else I noticed sitting in these conference meetings, because these were spaces are overwhelmingly male, that the sound of the laughter was very bassy. So that was something that I was also putting in this piece.

And in these office sketches, all of them, I was thinking about how we have to hide or make up for these non-normative parts of our identities when we’re in these workplaces. And the further one is away from the white male ideal of the employee, the more one has to work to fit in. And there’s more cognitive dissonance or gaslighting that you face trying to just insist on the validity of your own experiences.

So, this next one I will show… This one takes place in my office bathroom. And again, I will play a bit and turn the sound down.

https://vimeo.com/377625062

So, in the beginning you see me typing out the Morse code for “SOS.” And I’m hitting arbitrary numbers and just using the sounds of the beeps to do that. And the bathroom I think is supposed to be a place of solace, because it’s supposed to be a private place. It’s somewhere you can go to cry, to relax, to gather yourself—obviously to relieve yourself. It’s a very human and vulnerable place, and it’s one that all of us need. And supposedly it’s a place without surveillance. But office bathrooms are a whole other story.

In this bathroom you can see that the walls and the stall doors don’t touch the floor. So anybody who’s in there can monitor the other occupants. In my office, this one that you see here, bathrooms weren’t gender neutral, so they’re also a place where your gender is scrutinized and surveilled. I mean the fact that there’s even a key code to get into those bathrooms says a lot about how they’re trying to control the space as well. And I as far as I know never worked in a workplace where they tracked the length and frequency of my bathroom breaks, but that certainly is an issue for many workers. So the politics of bathroom architecture and bathroom tracking is another way we declare who a normative worker is.

https://vimeo.com/364936476

And the last one that I will from this series is this one. So this one the sound is really just my walking, so I’m just gonna talk over it. But this one, again not the most original title, is called Office Plants.

So I remember this one time walking down the hallway at Google and suddenly noticing that there was a lot more plants. I think that they had just installed a plant wall and it just like…it just felt really different. And I hadn’t really thought that much about it at the time, kind of filed it away, but in this office that I was working in, many years later I started noticing all these plants again. It’s hard to miss them. The office was just like filled with plants. And even all the photographs on the walls, which you saw a few of, were photographs of plants.

And so I started wondering how did we all end up here, you know, in this box? The windows that don’t open under these terrible fluorescent lights. We both just kind of exist in service of this company. And so I started looking into the history of office plants. And as I began researching, I realized that the history of office plants is basically the story of European colonialism. And I started learning about the central role of plants and plant theft and the plant trade in the success of the European colonial enterprise. And while there were plants that Europeans stole to cultivate in plantations, many plants were taken as scientific curiosities and to quench the thirst of rich Europeans who wanted to present themselves as worldly individuals by showing off a vast collection of so-called exotic plants. And we see that colonial legacy in the way that tech companies use and display plants in their office spaces today.

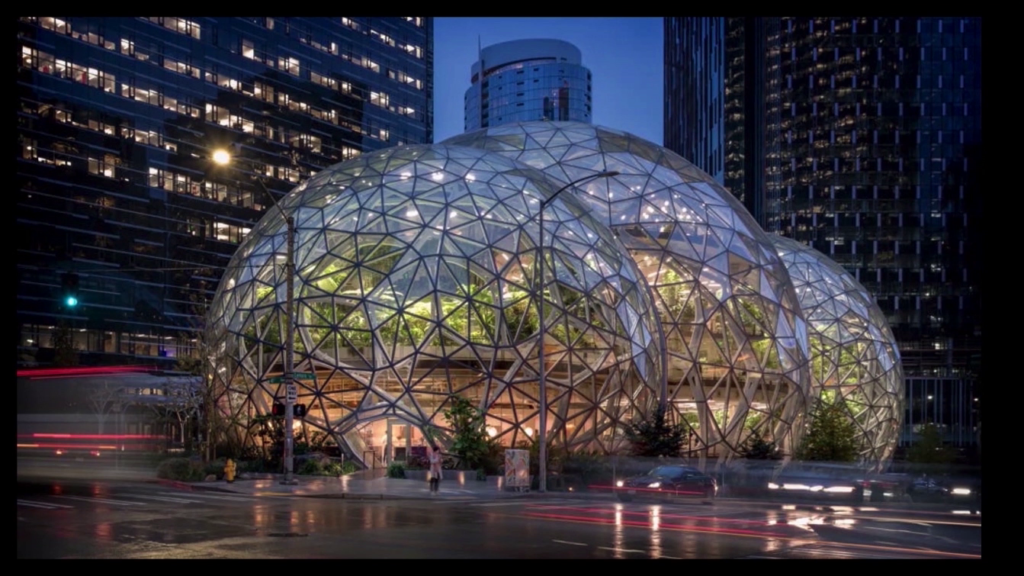

So during the colonial era, wealthy people would build these huge greenhouses. Glass was very expensive, and that was just kind of a way for them to telegraph their wealth. And tech companies today likewise build these elaborate greenhouses and plant walls as a way to signal their wealth and their success. Living walls and greenhouses are still incredibly expensive to build and maintain. And just think about the plants and how they exist in this space in relationship to the quote I shared earlier about the white spatial imaginary. The plants are a very carefully curated, cultivated, and maintained version of nature. And they are really just commodities. They’re there to serve a PR purpose.

So, I felt a kinship with this plant, the one you—well, all of them, but the one you see me taking a cutting of specifically, because it was right in front of my desk. And I also realized that there really wasn’t a way for me to help this plant. The best I could do perhaps was to take a cutting and maybe someday plant that cutting somewhere where it could thrive. But even that, taking a cutting, is a violent act. So kind of it was a recognition of how colonialism and capitalism have touched every part of our world. We can’t just cut off a part and run away. There’s really no easy fix, and in reality I don’t think there’s really a way out without pain.

And so this brings me to some of what I am thinking about and working on in 2020.

So, in 2020 as we all know, everything was totally turned on its head. I wasn’t working at this job anymore. And even if I was, I wouldn’t have had access to this office space to continue making this kind of work. I also moved across the country during this time, in hopes that school would be partially offline but it’s been entirely virtual so far. And so trying to get to know a new place and a new community without actually being able to go outside, really, or go anywhere and get to know the place has been very discombobulating. And as I have mentioned a few times, place is a really important part of my work. So even before those office sketches, the screenshots you see here are of two video performances, one where I traveled out to a Tesla factory, and another in front of an Amazon warehouse and created performances that were reacting to the physical location and presence of those buildings. And so doing this kind of stuff wasn’t really possible. So, this is one of the first things I did, which is very different than what I had been doing before.

https://vimeo.com/467239631

I took a time-lapse. I’ve been very interested in time-lapse and getting better at them. This one was just one photo a day so its very jerky. But I took a time-lapse of the cutting that I’d taken from the monstera, first rooting it in water and then transferring to a pot of soil. And then I took that time-lapse and put it with all these black and white images of Wardian cases. So the Wardian case was a technology that was created during the colonial era, and it was used to ship plants. So prior to the creation of the Wardian case, they would just kind of ships seeds, “they” being the colonists, would ship seeds and many of the seats would go bad on these like month-long sea voyages. But with this Wardian case which is essentially a terrarium, they were able to ship living plants, which are much hardier so they had a much higher rate of success of moving these plants all around the world. And this completely changed what they were able to do, where the colonists were able to go, the kind of plantations and plants they were able to cultivate. And I mean, even today we have plants from all over the world kind of growing—especially in a place like Los Angeles you have plants from everywhere growing here. So you know, this is all that legacy.

And I was also thinking a lot, as I mentioned before, about plants and tech companies particularly. And so this led me to these guys. These are Amazon’s biospheres. So Amazon built these huge biospheres, which are just big greenhouses, in downtown Seattle. And in different circumstances I would’ve loved to travel out to Seattle and somehow interact with these actual spheres and the workers that were working in this place. But of course that’s not possible. So when I was thinking about what to do and trying to plan this performance—when I plan these performances I usually spend a lot of time on Google Maps or watching videos or looking at other people’s photographs trying to get to know a place before I can travel out there, if I travel out there. So I was looking at all these YouTube videos and trying to decide what to do, and I kind of decided that you know, I’m not going to be able to do something physical so maybe I’ll just kind of continue with this digital collage format. And so I will show this one.

Still from 25000 Plants rough cut

So, basically what this is is the horticulturalist at Amazon giving a tour to a newsperson, newscaster, local news station about these Amazon spheres. And like, talk about the legacy of colonialism in the tech industry. There really is no better example than Amazon and Jeff Bezos right now. So this is still in progress. I’m now kind of thinking about it, making things that happen when you kind of step through this wall. But really this was kind of just something that I thought was fun to do, it’s something I’ve been doing a lot more of recently, is taking existing videos from online and inserting myself into them or otherwise kind of playing with them to heighten and point out the ridiculousness of what they are talking about.

So, the last thing that I will show today is another thing that’s kind of in progress. But I’ve been working on these infinitely-looping videos. And I’ve been also using myself a lot in these works. But in each of these videos I’m repeating a phrase which is something that I’ve heard or heard others say or I’ve said myself to justify my work in the tech industry, and pairing each of these phrases with a piece of office furniture. And so I kind of mocked these up quickly. I’m in the process of putting backgrounds in. But I mocked these up quickly to give you a sense of what these might look like. So I won’t play all of them, but in this one with the red, I’m saying, “I can do good at scale.” This one is, “We’re like a family here.” And this one, which I’ll share, is, “I can change things from the inside.”

https://vimeo.com/496751185

So sorry it’s a bit quiet, but I’ve kind of gotten really interested in this infinite loop as a way to express this feeling when you’re kind of stuck in this place or in this industry and making things that maybe you don’t feel excited about or believe in. But you’re not really sure how to leave. And so these are kind of the stories that we tell ourselves, like “I can change things from the inside” but really…can we?

And so this is actually I guess a question that I get a lot from people, is you know, can I change things from the inside? Should I just leave the tech industry? What should I do? Especially for our fellow people who identify as anti-imperialist and anti-colonialist, anti-racist, all these like…anti all these terrible things. Like how can we exist in this industry and make work for these companies if we feel so terrible about a lot of the things that they’re doing or what they stand for.

And I don’t necessarily think you have to leave the tech industry. I think that’s a very personal, individual decision that folks have to make depending on a lot of things about personal circumstances. But I do encourage people to be honest with themselves, ourselves, about what the companies we work for are doing and what our place in those companies is.

And yeah, so these are some of the things that I’m working and thinking about and I wanted to share with you all.

And I just wanted to share quickly a behind-the-scenes shot of what this looks like in my apartment right now. It’s been interesting this past year. And so I know this is probably a bit different than a lot of the other talks tonight regarding code, but I hope that I have encouraged you to think about the history and politics of the tech industry for folks who work in tech, and what it means to be somebody who’s working with and creating new technology. Because I think artists are the ones who are rethinking tech and building tech totally outside of these systems. And so there’s so much hope in what you all are doing. And I really love chatting with folks about all these ideas. And I would love to meet each and every one of you, so hopefully I will see you in the Discord or on email or in other places. Thank you.

Golan Levin: Thank you, Ann. There’s a lot to think about. And as you and I have discussed sometime ago when we were talking, your work has a relationship to code that apart from your own use of it from time to time is really…you’ve telescoped out so far that we can really think about the structures in which code is used and the ways we relate to it. I’m just grateful so much for your talk.

There’s wonderful questions in the discord. Claire is commenting how it’s interesting to think about office-made as a subset of homemade. And some of the other presenters made work which was…the intended audience is sort of the bored at work people. And in relationship to the bored at home network, your work has a relationship there.

There’s a question from Andy Quitmeyer in the chat here, which I’m gonna look at. And he asks, “With so many corporate jobs moved to homes, is there a new digital version of some of these things that ann describes that the corporations push? What’s the digital monstera plant or the digital locked bathroom?”

ann haeyoung: Yeah, that’s an excellent question. I guess I’m curious to hear from all of you know like what those might be. I mean the virtual background I guess is something that is this strange thing that we’re interacting with. I know different companies are sending physical things, like maybe delivering food or things like that that could be something…like a strange interaction that’s happening? There’s also a lot happening with companies that are tracking the amount of time that you’re spending in the workplace.

But I guess that doesn’t quite answer the question, but something I am really thinking more about is like, what the relationship with digital scans of things, and if that is also a form of colonization. And there are other artists like Morehshin Allahyari who’s done a ton of work about digital colonialism. But that’s something I’ve been thinking about recently, is like if we create virtual spaces that are filled with these kinds of plants and things like that, is that a form of like recolonization or digital colonialism? Or is that somehow kinder and more freeing? I don’t know. So, those are some half-baked thoughts, but I’d love to talk about that more with you.

Levin: There’s remarks about the irony of amazon.com and how instead of helping the actual Amazon, they sort of dumped crazy money into this weird simulacrum.

haeyoung: Yeah.

Levin: There’s another—a practical question. For the in-office videos, it was your office, right? Did you ask permission and explain your project? Which must’ve been a fun conversation with management. Or did you just sneak in in the weekend?

haeyoung: I just snuck in on the weekends. And I have been told that they have seen the videos and think they’re weird. So that’s cool.

Levin: It’s a pretty generic office. You weren’t revealing any corporate secrets.

haeyoung: Yeah, that’s what I figured.

Levin: Vernelle Noel, who is speaking next, she asks, “Question: the plant video is still in my mind. It feels like a Robin Hood bank/plant robbery. How do you come up with your concepts for what you want to say or question?”

haeyoung: Oh. Um… I don’t know. But like— I don’t know if it comes across this way but a lot of the stuff kind of starts as a joke. I like making work that makes myself laugh. And so a lot of this is a little bit like tongue in cheek, as I’m approaching it. And like I said, for me I’m sitting in this office every day for like two years and staring at this plant. So I have a lot of time to think about like, what I want my interaction with this plant to be. So yeah, I don’t think I have a really good answer for that, just kind of like staring at things a lot.

Levin: I think— This is just a personal reflection. I think a lot of your work has the quality of a joke. I agree it clearly starts with a joke, and it’s like a joke that I know you get, and then I want to understand it myself because there’s a…it’s not as simple as a joke. There’s a multi-layered palimpsest kind of multivalent quality to it, or a nonverbal quality to it. So I’m like this is funny but do I understand how. It’s really interesting.

I can’t wait for you to see all the great comments about your projects and presentation in the discord. I want to thank you so much ann for your gift of your time today. And we’ll see you around. Can’t wait to see what you produce next. Thank you so much for your time.

haeyoung: Thank you so much, everyone.