I’ve got the second-best title in the world. There’s a guy who works in the Natural History Museum and he’s the curator of cockroaches. But I get invited to more parties, so hey.

Thanks to you all for coming, and for the opportunity to put our heads in the same space around food and literature and agri-tech. I’m a literary critic, and it’s great to be able to bring literary criticism and techno-ethics together at the Congress. One of the things I’ve noticed about C3 events is that solutions often seem to present themselves at the intersections of different kinds of knowledge and practices.

I’m going to be talking about how the arts engage ethically and politically with the technization of the food chain, the chain or flow of sustenance from field to dinner plate. This is an inter-disciplinary talk but don’t worry, I won’t be claiming quite that poems and paintings are computational machines for working out social policy, because that would be crazy. But if I’m not willfully misunderstanding Joscha’s excellent talk on the computational universe, it seems that a likely candidate for the substrate of consciousness is the numinal, the realm of ideas, and that’s precisely where art and literature lives. So it’s the ideal place for deep processing of ethical issues, the big issues like food and tech.

I’m going to start with a general point. In 1783, the English poet George Crabbe described the brutal reality of inequal access to food. This is how he put it:

Where Plenty smiles – alas! she smiles for few,

And those who taste not, yet behold her store,

Are as the slaves that dig the golden ore,

The wealth around them makes them doubly poor

George Crabbe, The Village (1783)

Maybe that sounds familiar, because if Crabbe fell through a wormhole and arrived in the present day, he’d feel depressingly at home.

In 2014, almost a million people in the UK were forced to rely on food banks. It’s amazing that while agri-tech is bringing all kinds of awesome new capabilities online, from synthetic food to cisgenics and agri-robots, an all-party report concluded that hunger now stalks the UK. Actually, there were more than enough calories to go around. But the equivalent of fifty million meals a month went not to the hungry but straight to landfill or the incinerator.

We can talk about the regulations that compel supermarkets to do this, and we can play with the idea of regs that might stop them from doing it, but actually there is another layer of debate underneath that. Because what we seem to be witnessing, and not just in Britain, is the new socialization of hunger. Hunger presented as the inevitable consequence of austerity. Hunger that allows us to believe in austerity. Hunger as a deeply-embedded subroutine of cultural capitalism.

So where’s agri-tech in the equation? It seems to be where we’re placing our faith.

Technological advancement will be the only way we can meet the coming growth in demand.

Julie Girling (MEP), (European Environment, Fisheries and Agriculture committees) [link]

That’s the European Parliament.

…the reorientation of technology [as] the key link between humans and nature.

UN Documents, “Our Common Future”

The UN adopts a rather more conceptualized position, seeing tech as the key link between humans and nature. But what I and my co-researchers Jayne Archer, also a literary critic, and Sid Thomas, a plant geneticist, suggest in our new book is that art and literature already provide that deep processing link between humans and the bio-physical world. Moreover, that art opens a shared space of imagination that can be as radical as we need it to be.

Food security is a deceptively simple term. But it’s a dauntingly complex problem, and it encompasses land ownership, soil climate, climate change, markets, policies, and any solution lies at the intersection of a number of disciplines. We’ve got to bring together food producers, scientists, agri-tech, distributors, planners, and we argue, artists and writers. But first we have to rescue some of our canonical authors from the heritage industry. Authors who were once sharply critical of orthodox power have been re-packaged as our national poets and painters, and are given back to us in ways that make their art appear to support the codes and values of the dominant interests that they once challenged. Literary criticism can help us there with our counter-narratives. Because the truth is many of our best-known painters and writers, their relation to the politics of hunger, to early forms of agricultural technology, was a lot closer than ours, and their experience is relevant to the big actions that we need to define and take.

Consider Williams Shakespeare. Last year we made the newspapers with some research on Shakespeare’s business dealings. We argued that these dealings informed Shakespeare’s representation of food and bio-resources in the plays. It upset a lot of people who were actually quite happy with their image of Shakespeare as a safe writer, somebody who wrote on the big abstract themes like love, ambition, and envy. In fact, that sanitized “PR” version of Shakespeare began from an early stage.

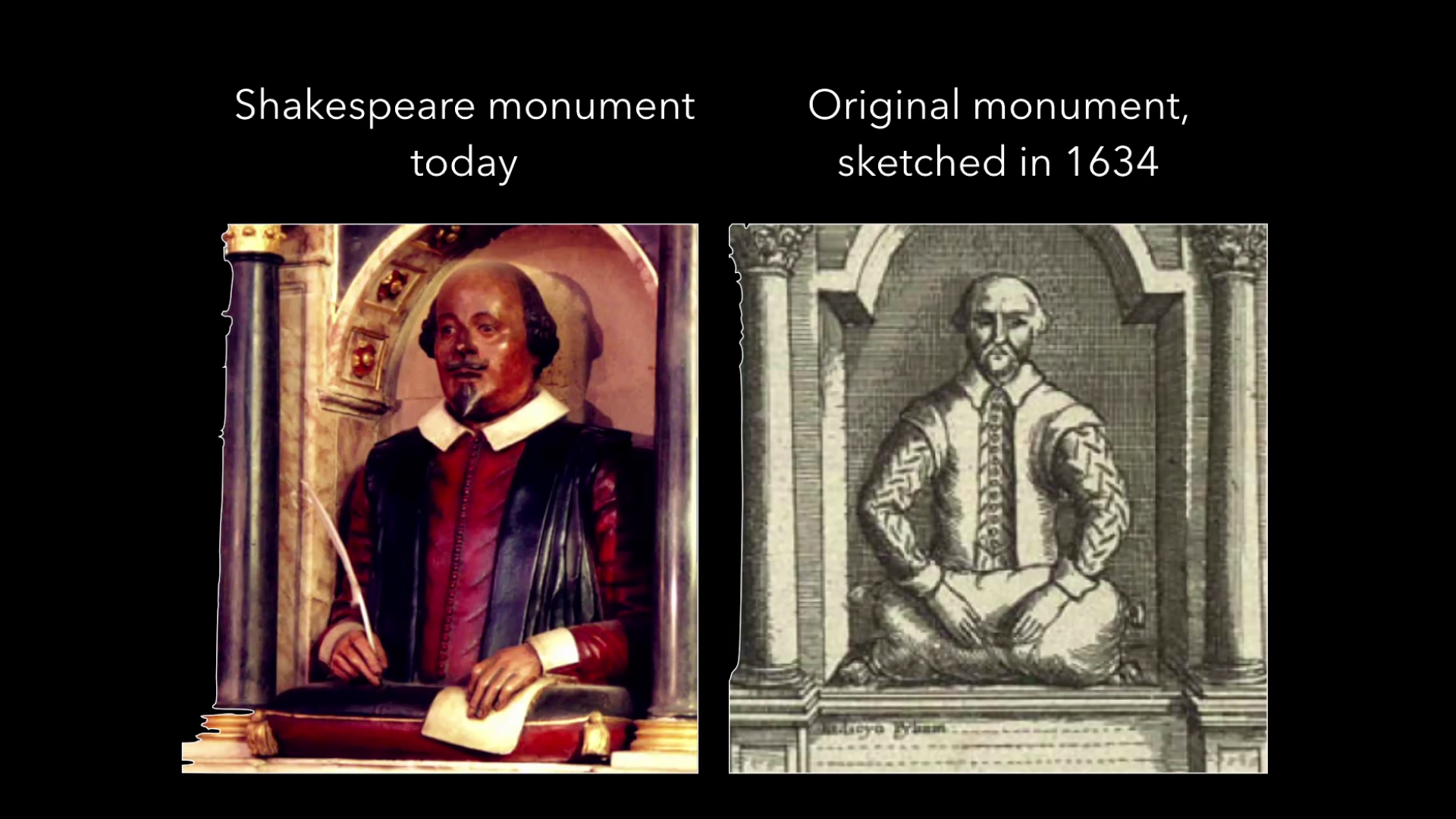

This is his funerary monument in Stratford, and it presents a familiar picture of a man of letters, his arm poised pregnantly, quill in hand above a velvet writing cushion complete with golden tassels. But actually this isn’t the original version of the monument. It’s an 18th century refurb, and it responds to Shakespeare’s by then already-developing reputation as a national poet. The original monument, which was commissioned by people who actually knew Shakespeare, remembered a rather different man. A grain merchant. A tax avoider. A man who use the profits from his plays to invest in the grain markets, which at a time of famine Shakespeare hoarded in that all-important piece of agri-tech, a barn. He hoarded it there until the prices rose, and he was prosecuted for it.

In the original monument, the velvet writing cushion is a sack of corn, and those golden tassels are actually roughly-tied edges. And maybe it won’t surprise you then to know that references to food prices and the societal impact of unequal access to food are bound in Shakespeare’s plays, and we should take them seriously.

But let’s consider these themes first in a contemporary novel, Daniel Suarez’ thriller Freedom™; it was published in Germany as Dark Net. I’m sure many of you’ll know it picks up a year after Suarez’ first novel, Daemon, a year after Matthew Sobol, the mad hacker (Is there any other kind?) has unleashed a bot on the world’s multi-nationals, including a thinly-veiled Monsanto. After the chaos, darknet communities have arisen, and in a key set piece near the beginning Suarez, who is of course a technology consultant, gives us a vision of a tech-based food- and energy-independent society. Thanks to my daughter for making this slide:

In it farmer Hank Fossen shows us around one of the new darknet farms, and with a sweep of his arm he describes a green vista of tech-led sustainability. Fossen’s own daughter is glimpsed off to the left, instructing the newbs in hybridization and genetics, while other darknet farm workers are out in the grass prairies, all with D‑space callouts floating above their heads, visible to anyone who’s wearing darknet glasses.

Fossen turned into the farm’s long gravel driveway. There was an ornate D‑space 3D object in the shape of a cornucopia bursting with vegetables and fruits hanging above the entrance. He looked out to several acres of grain and other plants, waving in the breeze. “We use a mix of crops and animals to recharge fertility. We’re raising the animals on grass – not corn. It grows naturally here on the prairie, so it’s turning solar power into beef — no fossil fuels necessary … It’s all an integrated, sustainable system.”

Daniel Suarez, Freedom™

This is a nice and fairly standard utopic vision. I’d like to live there, right in that slide. But technology isn’t the answer, and the novel seems to know it. It’s not the whole answer. Because the dark side of D‑space, the dark side of the fab labs and the remote sensing, is the anti-hero Loki Stormbringer, whose lethal drone motorbikes eviscerate anybody who opposes the vision.

So the tech in this apparently idyllic scene of sustainable community is half-insight and half out, occupying entangled positions on two sides of an ethical boundary. Suarez’ vision of a tech-driven agrarian Utopia isn’t fanciful. Much of the tech’s already with us or emergent. The last twenty years have seen incredible advances in synthetic biology. Think human bacteria cheese. Vertical farming. Gene tech, new modelling techniques for phenotypes linked to sustainable animal productivity. Drones that monitor nitrogen levels in fields. Predictive farming. Agri-informatics. Open-source farms. At MIT they have an open-ag project which is working towards the creation of the global agricultural information commons. And there’s some amazing research into agri-robots at the European Agri-robots Network, where Simon Blackmore’s team is working. They’re producing a new, light-weight generation of robots that follow the contours of fields rather than forcing farmers to plant in straight lines to suit older machinery. These robots spray only the part of the field that’s actually infected with disease, rather than the whole field.

My own university, in the wake of recent European food hygiene and fraud scandals such as Horsegate, has developed hyperspectral analysis techniques for detecting contamination of meat using fluorescent markers. Aberystwyth is also home to a major plant breeding and phenomics lab, kitted out with high-resolution metabolomics technology, and that uses content plant phenotyping to design smart crop varieties that are more resilient to changing climate. So it’s a brave new world of knowledge-led development that should improve not only food safety but also access to food.

But to return to Fossen Farm. Suarez’ vision of a knowledge-led sustainable future registers tremors of anxiety precisely about the tech that’s supposed to sustain it, and in that respect the novel belongs to a long tradition of art and literature depicting scenes of agricultural work. One of the best-loved, though we’d argue most misunderstood, examples is John Constable’s painting The Hay Wain, from 1821. It’s a visual precursor to Suarez. The passage I just read out belongs in this tradition. The Hay Wain is one of the worlds most recognizable paintings and seems to offer a calm, comforting representation of abundance and timelessness, and in many ways it’s come to stand for the establishment. And for that reason, it’s been the target of subversion. In 1980 the artist Peter Kennard hacked it to make The Hay Wain with cruise missiles. And last year a member of the British political group Fathers For Justice glued a photo of his son (pixelated there) on the canvas:

But ironically, we’ve lost the ability to perceive the painting’s own radical politics. So let’s look more closely. In the foreground is a piece of then-contemporary agri-tech, an unladen hay wagon, an example of how art delivers back to us, in a materialist sense, a sense of how we fit into the human race, in the idiom of the technology of the time we find ourselves in. Agri-robots now, hay wains then. But despite the painting’s popularity, it’s every bit as radical as Suarez’ novel, and it’s making more or less exactly the same point. Because the hay wagon has a far more contentious counterpart, tech that’s also just out of sight but definitely not out of mind, and it’s actually the key to the nexus of social, political, and economic energy that’s been coded into this famous canvas.

Let’s take a step back. The first thing we need to know is that the painter, John Constable, was the son of a miller and a landowner, and it’s his father’s fields, his father’s tech, his father’s workers, that we see in the painting. Indeed a cynic might say that the role of public art on this scale is precisely to inculcate us into the values of a world of concentrated wealth and sharply-demarcated society. But leaving Constable’s own politics aside for the moment, let’s try to listen to what the painting’s actually telling us. Let’s produce a counter-narrative. Because almost everything we’ve been told to think about this idyllic scene, everything we’ve been told by all those biscuit tin lids and mobile phone cases, is actually wrong, starting with the painting’s official catalog description, which tells us that the hay wain is standing in the water.

If the wagon’s stationary, it’s not because it’s been posed aesthetically for us. If anything it looks like it’s become stuck, perhaps in mud, the river swollen from the rain that’s already begun to fall further upstream. Constable painted the hay wain in an unusually wet year, and it caused big problems for farmers in the region and drove down laborer’s wages, including the wages of everyone we see in that painting. The wagon should be going hell for leather, as becomes clear once you realize there’s not one but two hay wains.

So the title of the painting is also a little bit dodgy. There’s the second one, off to the right, it’s tiny. And while one is loading the other is unloading because what’s Constable’s depicting here is dynamic process, not a sentimental still life. So we know where the wagon’s going, but where has it come from? Where has it just unloaded its hay? The candidate that’s usually offered is Constable’s father’s water mill itself. But mills grind wheat and barley, they don’t mill hay. You can’t mill hay. The piece of tech that’s out of sight is behind Constable’s easel. It’s a barn.

That’s the tech the painting struggles with. It’s the tech that adds value to the grass that’s being harvested. The tech which, as Shakespeare knew, turns a crop into data, abstracting it from a field and from a local economy into the realms of markets and price indexes. And it’s the tech which for that very reason was the first thing to get burned down in times of food unrest. Basically, Constable’s father is making a killing off the backs of those low-paid hay makers and wagoners.

This painting isn’t so much art, it’s evidence, and those wagoners are doing their best to get going again, for good reason. They want to keep even their low-paid jobs, because while we may not have a Loki Stormbringer, we do have an approaching storm:

And as an agricultural journal from the period explains, it was the hay makers’ and wagoners’ responsibility to get the crop in dry.

In the case of approaching rain, when the hay is fit for carrying, every nerve is, or ought to be, exerted to get all the carts and wagons loaded, and drawn into the barns.

John Middleton, General View of the Agriculture of Middlesex (1813)

So this isn’t a mythic field, it’s not timeless, it’s not a patriotic image of Old England with a sentimental, historically-stranded piece of farm equipment in the foreground. Rather, the field and Constable’s painting itself exist at the troubled intersection of agrarian market economics, social ethics, and agri-tech. Agri-tech that privileged landowners while disenfranchising workers and whole communities, because behind the unseen barn is a region of England that was still recovering from violent food riots five years earlier, which had seen many hayricks and barns burned down. Two local agricultural workers were hanged, and others were transported to Australia. And just one year later in 1822, the region erupted again in so-called “bread or blood” riots. Perhaps some of Constable’s own workers were involved in that direct action.

So the longitudinal story that art and literature is telling us is unambiguous. A dysfunctional food chain has only one outcome: food unrest. And in an age of information, on a potentially massive scale. So of course we’re right to look to tech to increase yields and to reduce environmental impacts of agriculture. But if we’re going to develop the resilience we need as we attempt to manage the bio-physical world in the difficult times that are surely coming, what William Gibson’s new novel The Peripheral calls, with infinite irony, The Jackpot, the simultaneous arrival of climate, capital, and crop disaster, then we need to expand out thinking about food system into the imaginative world, because the alternative isn’t pretty. And it’s already happening.

As Constable and his father knew only too well, the canonical response to hunger is the food riot. The situation in the UK at the moment is particularly incendiary around food banks because, as in Crabbe’s poem, at the same time as the new underclass of the hungry is driven to charity handouts, it suffers the indignity of watching as the top few percent enjoy what Thomas Picketty calls “vertiginous growth.”

In 2012 London experienced a week of rioting. In the media, almost without exception—scandalously—the action was presented as senseless violence by mindless thugs in pursuit of branded trainers and flat-screen TVs. In fact, the first shop to be looted wasn’t a TV warehouse, it wasn’t a designer bag outlet. It was the Clarence convenience store. Here you can see young men clambering over the counter, chocolate bars and water bottles in their pockets.

The London Riots, or uprising as some prefer to call them, in its early stages at least, started out as a traditional food riot.

The so-called food crisis/social unrest hyphothesis suggests that large-scale discontent around the world can be mapped with chilling precision onto indexes of staples like rice and wheat, and the FAO’s food price index measures the monthly change in international prices of a basket of food. And basically, if that goes above 210, you get riots across the world. This includes crowd action with obvious food connections like the 2008 Mexican tortilla riots, but the 2011 Arab Spring, and 2013 Gezi Park protests also map neatly onto these spikes. And prices of staples and commodities are projected by the FAO’s own figures to rise by 40% over the coming decade.

To conclude, then. We’re not facing food crisis for the first time, and we’re not facing it alone. Literature and art have processed many such moments of emergency, examining food crisis in deep imaginative space. From Shakespeare’s play Coriolanus, where Rome’s corn supplies are withheld from the plebians much as Shakespeare withheld corn in the Stratford area, to Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games trilogy.

Let’s end with The Hunger Games. Katniss Everdeen, the figurehead of rebellion against the repressive state remarks it “must be very fragile, if a handful of berries can bring it down.” But the fact is political and power systems have often been challenged or overturned by the decision to eat or not to eat.

Thank you for listening.

Audience 1: Thank you, very interesting. I would like to ask you, are you going to do some research in the prehistory of food production and food consumption.

Richard: Our project goes back to 1380-something, to Chaucer. That’s where we started. We’re looking at The Canterbury Tales as a game of food, basically. Once you start looking in canonical art, which I guess we’ve been taught to assume is safe and comforting, you start to see all sorts of interesting things. But I should say the reason why we’re doing it and why going back to prehistory would be really interesting, is because before we can start putting into effect the kind of benefits that we can expect from agri-tech, we need to change headspace.

I think Slavoj Žižek is absolutely right when he criticizes Thomas Picketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century. He says it’s utopian to say that the solution to the problem of wealth outgrowing economic output is simply to redefine the ratios of distribution so the rich get more tax and the poor get more benefits. Because if you do that, capital simply moves, or you get other knock-on effects that inevitably end up privileging wealth. So the real challenge as Žižek says is that you have to create the right conditions that enable you to enact things like say, taxing wealth at 80%. And literary criticism can be a really powerful tool in bringing about those conditions, and I think the further we push the analysis back, the richer the data’s going to become. So thanks for the question.

Audience 2: Beautiful talk, and since I’m writing a book on barns, I’m of course curious if you can help me with two questions. First of all, how old are barns? When do they appear? And that leads me to the second question because the way you depicted barns here is that they’re sort of an intermediary space between the agricultural world and the market. So that would make them pretty modern. In my view, I always thought [of] the barn as different from the warehouse, as not really something like a warehouse, which is intermediary space where the market comes to a stop until some demand calls for the good to be called out and so forth. So I wonder what’s your take on the position of the barn in this longer history of capitalism.

Richard: It is a great question and again a question with a sort of longitudinal momentum. So you’re de-synonymizing barn from warehouse, and you’re right to do that. The barn occupies a different position in social space, and I guess we think of warehouses as more to do with imports and exports, maybe. Great, we need to do that. We haven’t actually focused the entire study on the physical space of the barn, but more of the barn conceptually as that mediating point between markets and communities.

Audience 3: Thank you. I have a question; I will try to articulate it well. With Shakespeare’s time, and then the time of the painting compared to status quo. That layer of people between aristocracy and nobility, and indentured serfs, was there a difference in perception of how close or how far they were to this abyss, and where would you be reading for expressions of this in contemporary literature?

Richard: The position of the serf is interesting, and it interests me. I think the German word is Leibeigener. There was a bishop in the 18th century who joked that the only thing a serf possesses is a hungry belly. It’s a sick joke, a terrible joke. And I think in part part of that answers your question how close were serfs to the abyss. They were right on it, clinging on by their fingers at particular points.

Further Reference

Collected publications on food and literature from Richard, Jayne Archer, and Sid Thomas