Scott Atran: How comes it that humans make their greatest exertions, including killing and dying, not for their own gain, lives, or family, but for an idea? A transcendent moral conception they have of who I am and who we are. That’s the privilege of absurdity to which no creature but man is subject, which Hobbes wrote in Leviathan.

When I was ten I painted on my bedroom wall, “God exists, or if he doesn’t we’re in trouble.” It was 1962, the Cuban Missile Crisis. My father was grim. “Twenty, thirty percent chance, son,” he said when I’d asked if there would be nuclear war. He’d just briefed the Pentagon. US Sparrow missiles couldn’t knock down Soviet missiles. No greater absurdity ever seemed possible.

Later, doing anthropological field work with Maya committed to forest spirits trying to preserve the rain forests, and with would-be suicide bombers seeking glory and grace in killing and death, I found in both groups devoted actors committed to sacred values of their communities of imagined kin: motherland, brotherhood.

Now, with our team of policymakers, academics, former military, playwrights, we explore why people refuse political compromise, go to war, attempt revolution, or resort to terrorism, focusing on what Darwin called “those virtues highly-esteemed and even sacred,” that give immense advantage to any group with devoted actors inspired to sacrifice for them.

ISIS is a classic revolution, a moral mission to save the world whereas Robespierre put it for the French Revolution, “Terror is an emergency measure emanating from virtue. For without a claim to virtue, it’s inconceivable to do great good or commit mass murder.” But ISIS undermines everything dear to me, and so I bring science to the battlefront to help understand and stop it.

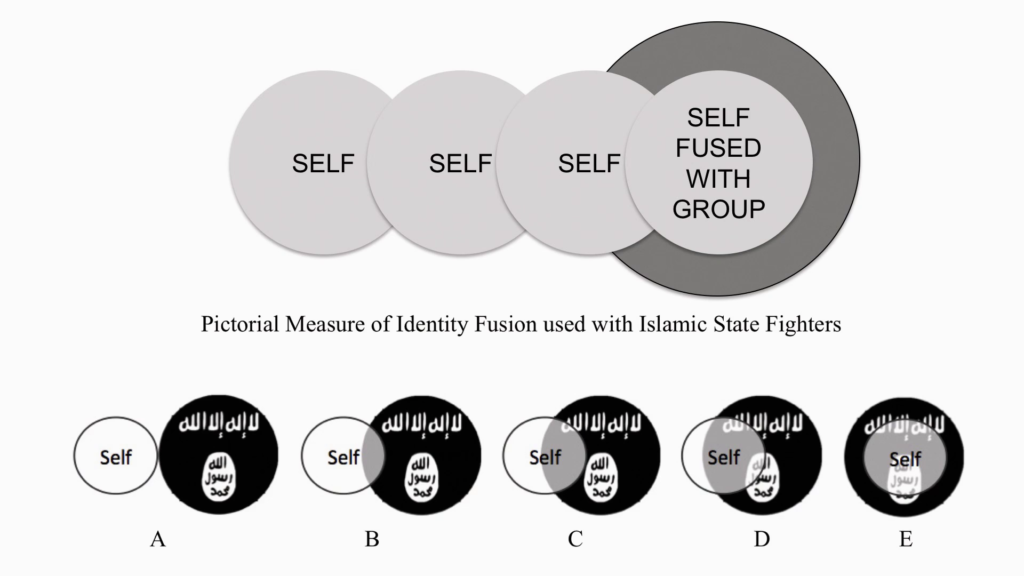

Our work on the front lines in Iraq and elsewhere suggests that unconditional cooperation and intractable conflict are best understood within a devoted actor versus rational actor framework that integrates research on sacred values (whether religious or sacred, as when land or law become holy or hallowed), and identity fusion, which gives a visceral sense of oneness to any group.

Consider a pair of circles (one is me, the larger one of the group), with different degrees of overlap between them. Those who choose the last pairing are fused with an individual personal identity, within the collective identity where each individual is willing to sacrifice for every other.

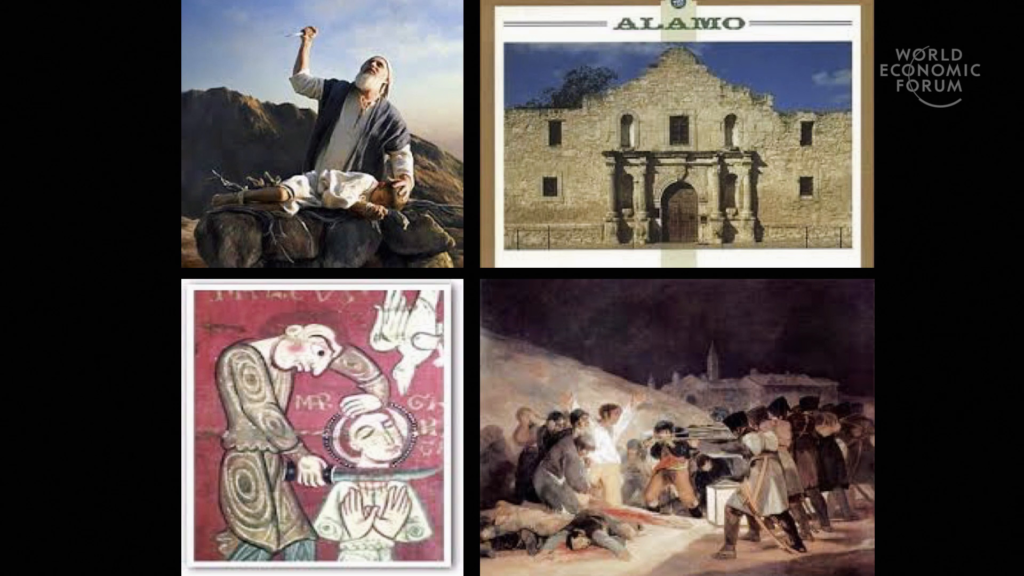

Now, much more is known about economic decisionmaking than value-driven decisionmaking. But here are some features of sacred values. They’re immune to material trade-offs. Most people wouldn’t sell their children or sell out their country or religion for all the money in China. They’re insensitive to spatial and temporal discounting, where distant events and places are more valued than the here and now. Consider the Second Coming, or the exodus from Egypt. And they generate actions independent of prospects of success. Offering people material incentives, however reasonable or rewarding, or punishments, or sanctions to abandon sacred values, only generates anger, violence, and opposition to peace.

Consider abortion or gun rights in America. Israel, Palestinians’ claim to the right of return. Or Russia’s feelings about the Crimea.

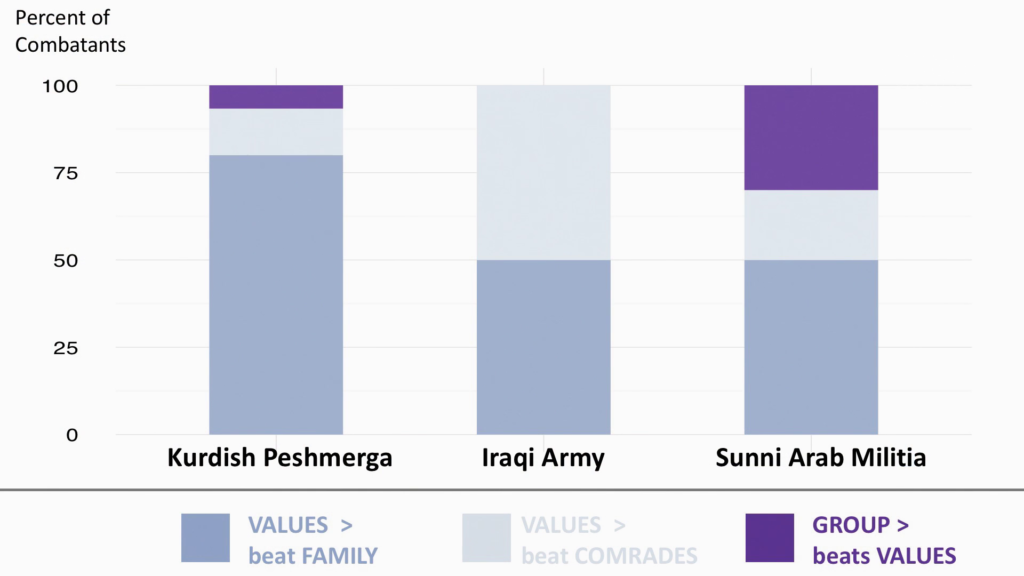

Now, our research with fighters shows that the US government’s judgment is fairly mistaken about underestimating ISIS and overestimating the armies against it. Because it denies the spiritual dimension of human conflict.

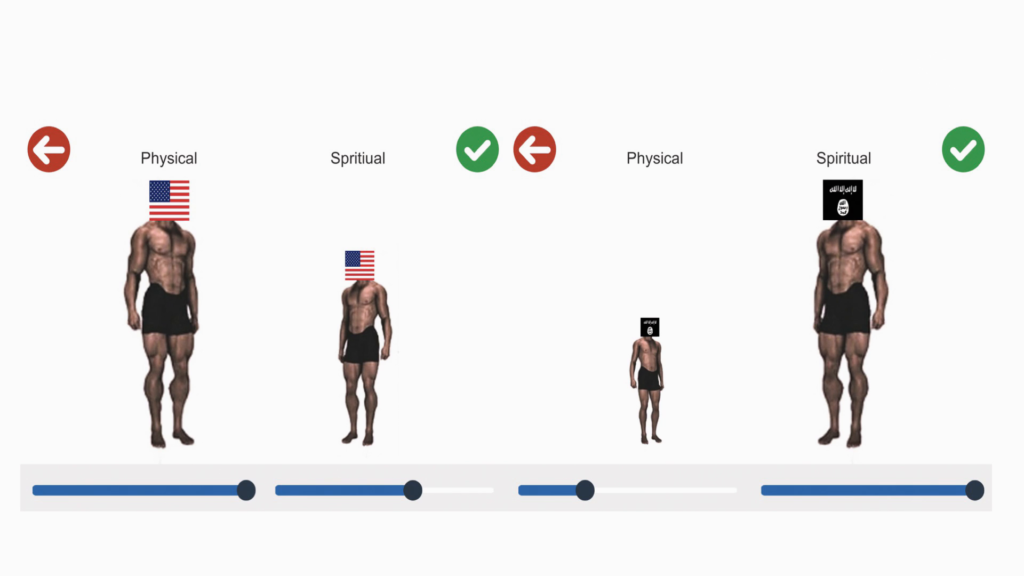

Three critical factors are involved. Sacred values and devotion to the groups people are fused with. Willing to sacrifice family for values. And perceived spiritual formidability. For example, among fighters on both sides in Iraq and Syria, they rate America’s physical force maximum, the spiritual force minimum. And ISIS’ physical force minimum, the spiritual force maximum. But, they also think material interests drive America, but that spiritual commitment drives ISIS. But spiritual trumps physical force when all things are equal.

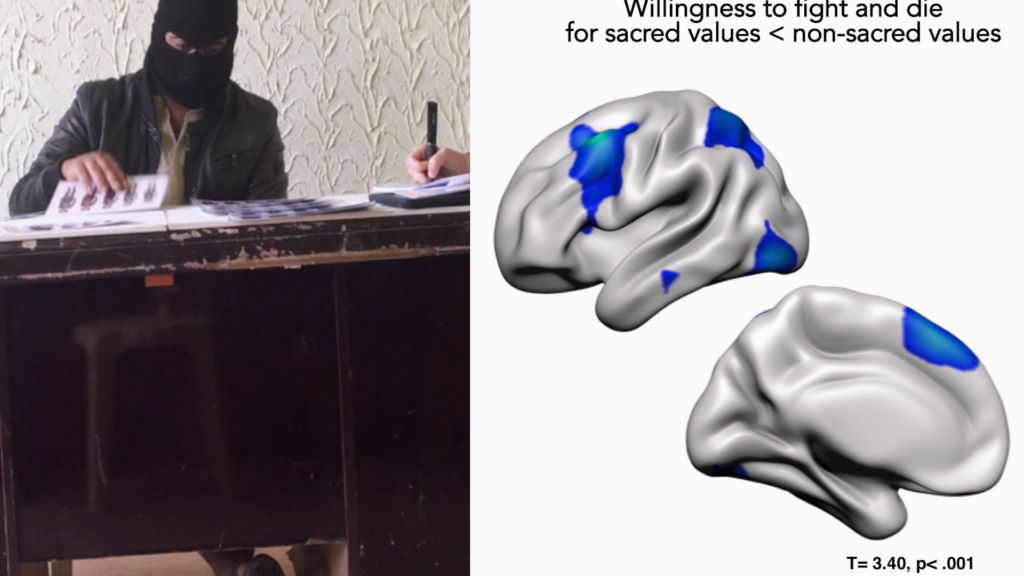

Brain scans of Lashkar-e-Taiba supporters for willingness to fight and die show decreased activity in those parts of the brain occupied with utilitarian reasoning, inhibiting the deliberative reasoning in favor of rapid duty-bound responses.

Now, civilizations rise and fall on the vitality of their cultural ideas, not material assets alone. Most societies have sacred values for which people would partially fight even unto death. As with many in ISIS and some, especially Kurds, who fight against this.

We find no compatible willingness to fight among Western youth. Government, business, academia, communities, have to work better to face violent extremism—especially with youth, who form the bulk of today’s terrorist recruits and tomorrow’s most vulnerable populations.

But most view youth as a problem to be clobbered rather than the promise of the solution, and the world’s most creative force. With the defeat of fascism and communism, have our lives defaulted to the quest for comfort and safety? Thank you.