Tali Sharot: By the end of today, 4 million blogs will be posted, 80 million Instagram photos uploaded, and 600 million tweets released into cyberspace. That’s more than 7,000 tweets per second.

Why do you spend precious moments every day sharing information? There’s probably many reasons, but it appears that the opportunity to impart your knowledge onto others is internally rewarding. A study conducted at Harvard showed that people were willing to forego payment in order to have their opinions broadcast to others. Now, we’re not talking well-crafted insights here. These were people’s opinions about whether Barack Obama enjoys winter sports, or whether coffee is better than tea.

A brain imaging study showed that when people had an opportunity to share these pearls of wisdom with others, their reward center in the brain was very strongly activated. You feel a burst of pleasure when you share your thoughts, and that drives you to communicate. It’s a nifty feature of our brain because it ensures that ideas are not buried with the person who first had them, and as a society we can benefit from the minds of many.

But for that to happen sharing is not enough. We need to cause a reaction in others. What then determines whether you affect the way people behave and think, or whether you’re ignored?

So, as a scientist I used to think that the answer was data. Get data, couple with logical thinking, that’s bound to change minds, right? So I went out to try and get said data. My colleagues and I conducted dozens of experiments to try and figure out what causes people to change their decisions, to update their beliefs, to rewrite their memories? We peeked into people’s brains, we recorded bodily responses, and we observed behavior.

So you can imagine my dismay when all of these experiments pointed to the fact that people are not in fact driven by facts. People do adore data. But facts and figures often fail to change beliefs and behavior. The problem with an approach that prioritizes information is that it ignores what makes us human. Our desires, our fears, our emotions, our prior beliefs, our hope.

Let me give you an example: climate change. My colleagues Cass Sunstein, Sebastian Bobadilla Suarez, Stephanie Lazzaro, and I wanted to know whether we could change the way people think about climate change with science. So first of all we asked all the volunteers did they believe in man-made climate change? Did they support the Paris Agreement? And based on their answers we divided them into the strong believers and the weak believers. We then told everyone that experts estimated that by 2100 the temperature would rise by six degrees, and please give us your own estimate. So, the weak believers gave an estimate that was lower than the strong believers.

Then came the real test. We told half of all the participants that the experts have reassessed their data, and now conclude that things are much much better than previously thought and the temperature would only rise by one to five degrees. We told the other half of participants that the experts have reassessed their data, and now concluded the things are much much worse than previously thought, and the temperature would rise by seven to even degrees, and please give us your own estimate.

The question was, would people take this information to change their beliefs? Indeed they did. But mostly when the information fit their preconceived notions. So when the weak believers heard that the experts are saying that actually things are not as as bad as previously thought, they were quick to change their estimate in that direction. But they didn’t budge when they learned that the experts are saying that actually things are much worse than previously predicted.

The strong believers showed the opposite pattern. So when they heard that the experts are saying that things are much more dire, they changed their estimate in that direction. But they didn’t move that much when they learned that the experts are saying that things are not that bad.

When you give people information, they are quick to adopt data that confirms their pre-notions, but often will look at counterevidence with a critical eye. This will cause polarization, which will expand and expand as people get more and more information.

What goes on inside our brain when we encounter disconforming opinions? Andreas Kappes, Read Montague, and I, invited volunteers into the lab in Paris. And we simultaneously scanned their brains in two MRI machines while they were making decisions about real estate and communicating those assessments to one another.

What we found was that when the pair agreed about a real estate, each person’s brain closely tracked the opinion of the other, and everyone became more confident. When the pair disagreed, the other person was simply ignored, and the brain failed to encode the nuances of that evaluation. In other words opinions are taken to heart and closely encoded by the brain mostly when it fits our own.

Is that true for all brains? Well, if you see yourself as highly analytical, brace yourself. People who have better quantitative skills seem to be more likely to twist data at will. In one study, 1,000 volunteers were given two data sets: one looking at skin treatment, the other at gun control laws. They were asked to look at the data and conclude: Is a skin treatment reducing skin rashes? Are the gun laws reducing crime?

What they found was that people with better math skills did a better job at analyzing the skin treatment data than the people with worse math skills. No surprise here. However, here’s the interesting part. The people with better math skills? They did worse at analyzing the gun control data. It seems that people were using their intelligence not necessarily to reach more accurate conclusions but rather to find fault with data that we’re unhappy with.

The question then becomes why have we evolved a brain that is happy to disregard perfectly good information when it doesn’t fit our own? This seems like potentially bad engineering, leaving errors in judgment. So why hasn’t this glitch been corrected for over the course of evolution?

Well, the brain assesses a piece of data in light of the information it already stores, because on average that is in fact the correct approach. For example, if I were to tell you that I saw pink elephants flying in the sky, you would conclude that I’m delusional or lying, as you should. When a piece of data doesn’t fit a belief that we hold strongly, that piece of data, on average, is in fact wrong. However, if I were to tell my young daughter that I saw pink elephants flying in the sky, most likely she would believe me, because she has yet to form strong beliefs about the world.

There are four factors that determine whether a piece of evidence will alter your belief: your current belief; your confidence in that current belief; the new piece of evidence; and your confidence in that piece of evidence. And the further away the piece of evidence is from your current belief, the less likely it is to change it. This is not an irrational way to change beliefs, but it does mean that strongly-held false beliefs are very hard to change.

There is one exception, though: when the counterevidence is exactly what you want to hear. For example, when people are told that others see them as much more attractive than they see themselves, they’re happy to change their self-perception. Or if you learn that your genes suggest that you’re much more resistant to disease than you thought, you’re quick to change your beliefs.

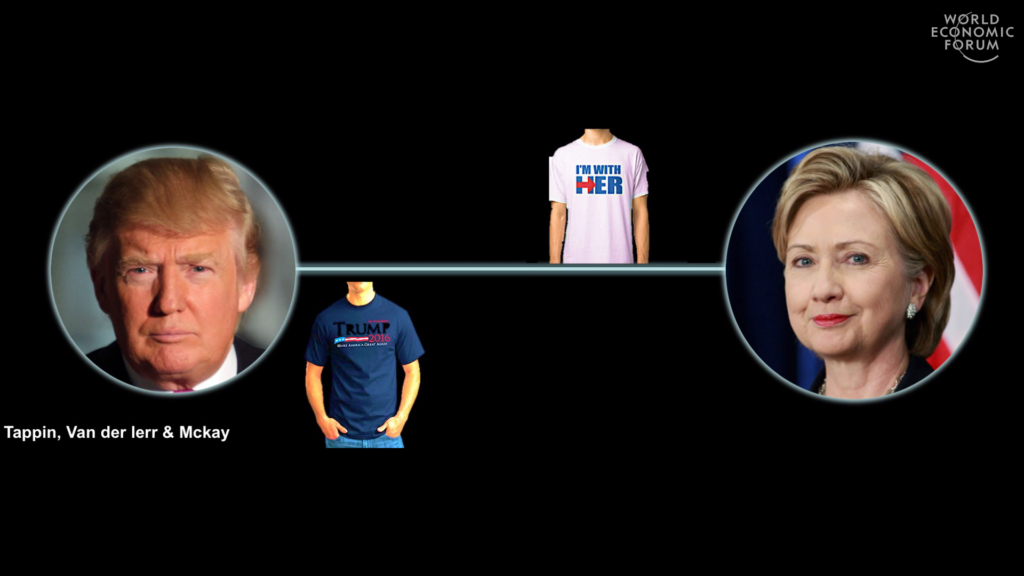

What about politics? Back in August, 900 American citizens were asked to predict the results of the presidential election by putting a little arrow on a scale that went from Clinton to Trump. So if you thought Clinton was highly likely to win you put the arrow right next to Clinton. If you thought it’s a 50/50, you put it in the middle. And so on and so forth. They were also asked, “Who do you want to win?”

So, half of the volunteers wanted Trump to win, and half wanted Clinton to win. But back in August, the majority of both the Trump supporters and the Clinton supporters believed that Clinton was going to win.

Then a new poll was introduced, predicting a Trump victory, and everyone was asked again, “Who do you think is going to win?” Did the new poll change their predictions? Indeed it did. But mostly it changed the predictions of the Trump supporters. They were elated to hear that the new poll was suggesting a Trump victory and were quick to change their predictions. The Clinton supporters didn’t change the predictions as much, and many of them ignored the new poll altogether.

The question then is how do we change beliefs? I mean, surely opinions do not remain stable, they do involve. So what can we do to facilitate change? The secret is to go along with how our brain works, not against it.

So, the brain tries to assess any piece of evidence in light of the knowledge it already stores. And when that piece of evidence doesn’t fit, it’s either ignored or substantially altered. Unless of course it’s exactly what you want to hear. So, perhaps instead of trying to break an existing belief, we can attempts to implant an new belief altogether and highlight the positive aspects of the information that we’re offering.

This all sounds very abstract, I know. Let me give you an example: vaccines. So, parents who refuse to vaccinate their kids because of the alleged linked to autism often are not convinced by science suggesting that there’s no link between the two. What to do then? A group of researchers, instead of trying to break that belief offered the parents more information about the benefits of the vaccine. True information. How it actually prevents kids from encountering deadly disease. And it worked.

So, when trying to change opinions, we need to consider the other person’s mind. What are their current beliefs? What are their motivations? When someone has a strong motive to believe something, even a hefty sack of evidence to the contrary will fall on deaf ears. So we need to present the evidence in a way that is more convincing to the other person, not necessarily in the way most convincing to us. Identify common motives and then use those to implant new beliefs. Thank you.