Moderator: So, our next speaker is a biohacker, a blogger, body mod artist, and a nurse. He’s collaborated on projects ranging from [?] peptides that extend ERM sleep all the way to non-newtonian armor implants. He actually hosts the annual event Grindfest in Tehachapi, California. A little fun fact about him, he actually placed third in the Biohack Village oxytocin poker tournament, and he performed an implant on transhumanist presidential candidate Zoltan Istvan. Now here to present his talk on “Biohackers Die,” ladies and gentlemen, Jeffrey Tibbetts.

Jeffrey Tibbetts: Okay, so. How’s it going? I’m a biohacker. And I have done a few high-profile grinds, okay. So a number of people in this room and I were on an MTV show, snorting a peptide called VIP that rat models have shown to radically alter circadian rhythms. It didn’t do much to our sleep cycles, but we did find that it seriously boosted visual memory function on two methods of testing. We’re still crunching the numbers on that study but I think I had a lot more fun last Defcon where we all snorted the oxytocin. That’s the so-called trust or bonding hormone. And we did this up in a hotel room and then competed in a poker tournament.

I’ve also done some critical work with nerve growth factors. And you know, we found that introducing NGF at the point of incision when implanting a magnet actually increases sensitivity and provides a better result in terms ability to perceive fields.

So essentially, where groups like Grindhouse Wetware or Cyberise or Dangerous Things are focusing really on creating technology to place in the body, my focus tends to be on ways to alter a person’s physiology or anatomy, which is basically the antithesis of my day job. As a registered nurse in an ER, my objective’s bringing people back into normal limits. I’m fortunate that I still get to be involved with all the cool new devices being developed because you always need someone willing to cut you open and shove things inside.

So I’ve done hundreds of procedures at this point, ranging in complexity from the quick poke of an RFID injector like you see Zoltan getting here, to bilateral armor implants running the length of the recipient’s shins.

As far as I can tell everything I do is legal and falls under laws pertaining to body modification. I mean, I think it’s legal. Of course, saying something’s legal doesn’t necessarily mean it’s safe, which is the focus of what I’m going to talk about today.

I’ve been active in the grinding community pretty much since its inception, and it’s only lately that I’ve really been willing to admit even to myself that someone’s gonna die, okay. And something’s going to go wrong and somebody will die.

So grinders are a community committed to radically altering the body. And so sometimes it’s treatments like transcranial magnetic, or direct current stimulation. It could be through the use of previously untested chemicals like VIP. Often it takes the form of implanted devices. All these approaches come with risks. What I’m going to focus on today is why despite all the risks being taken, a grinder hasn’t died yet.

If you didn’t know about Tim Cannon and Circadia prior to this Defcon, I’m sure you know now. People have had a lot to say about his project and not all of it was positive. I’m going to read three comments that I found about Tim.

I guess if you want flesh eating bacteria, sepsis and such, get one stuck into your body at a chop shop.

Jenn bioshockz the world on storyleak.com

The assumption underlying this type of comment’s that we’re all incompetent and with a total disregard for sterile technique and safety. Trust me this isn’t the case. I don’t know why, but media folk love to record arguments and family drama. But they always stop recording during the hours spent cleaning and autoclaving.

You idiots need to look more into potential side effects prior to doing these things.

Rlewein comment on Meet the grinders: The humans using tech to live forever

So on top of being incompetent, we’re also totally ignorant. Despite the months and in some cases even years that we spend on projects, people assume we know nothing at all. Once again this is not the case.

This is my favorite:

When it comes to something like cutting someone’s body open, skin open, and putting some foreign object under the skin, then it should be done by professional people, not just people at home.

Von Cyborg, quoted in The Half Life of Body Hacking

I like this one because it acknowledges that yes, someone out there has the skill to do this stuff but, it’s not us, right? I think the best way to address these concerns is by showing exactly how much knowledge and skill goes into even the most basic of procedures.

So first off yes, there are grinders that are performing procedures in their garages, okay. Let’s take a look at one.

It’s kinda cut off, but still. As you can see in the slide, all of the walls are non-porous. They’re wipeable. There’s a HEPA-filtered air supply. There’s overhead surgical lighting. There’s also a non-porous wipeable procedure chair. Off to the left where you can’t see, there’s a scrub sink. There’s a patient monitor. There’s an electrosurgical unit over stuffed in the corner. An IV pump. There’s a biohazard disposal bin. A sharps disposal bin. I’m still working on putting in oxygen and an air supply. Yes, this garage is not on par with an OR found in a hospital, but it’s better than most procedure rooms that you find in clinics, to be honest.

And the most important aspects of this entire room, though, is that it’s designed to be easily cleaned. And cleanliness is usually a critic’s first point of contention. Clean is not good enough, right? Contrary to popular belief, operating rooms are not sterile. The best you can hope for is disinfected. People mix up, all the time, sterilization and disinfection and antisepsis.

So, antiseptics are cleansers that reduce the number of pathogens on the skin. Grinders use either a mixture of 70% alcohol with a 4% chlorhexidine gluconate, or povidone-iodine 12% to disinfect the incision site. Either works. I prefer chlorhexidine because it has a residual action.

In terms of disinfectants, they are chemicals which kill the majority of infectious agents on a surface. We use a 1:10 dilution of bleach for surfaces, and quaternary ammonia for more delicate items like equipment and tubes and cords and things.

In terms of sterilization, sterilization is the elimination of all life. You’ve got to sterilize anything that touches the incision site, like tools and gauze. This is my Ritter M9-022. It works by bringing tools 121 Celsius at a pressure of 15 PSI for 30 minutes.

So, of course just having these tools and supplies doesn’t mean you’re using them right. And someone could totally still claim that we’re incompetent based off of this. But if I took the time to really explain how to scrub in and disinfect the environment and the use of the ultrasonic baths and enzymes and protectants prior to autoclaving, we’d never actually make it to my point. So, we are using them correctly.

So really I mean, are we competent? I know we’re competent as the guys working in the hospital OR, because I know those guys and I was trained by those guys, okay. And are we ignorant? Well, I guess the question I have is why aren’t operating rooms sterile? There was a grinder project a few years back where some people made a chamber, and the recipient would place his hand in the box and the whole procedure was performed by an artist reaching through this gloved aperture, right. They would fill the entire chamber with a vaporized disinfectant immediately before doing the procedure. I couldn’t find a picture of this.

But what I did find a picture of… This is a hydrogen peroxide vapor system being made by a company called Bioquell, and it’s been trialled at John Hopkins. I’d say no, we’re not ignorant. On the contrary we’re right at the forefront if not beyond what the medical field is already doing. I mean, this is being trialled at Johns Hopkins, we had a few years back someone already trying the same type of idea.

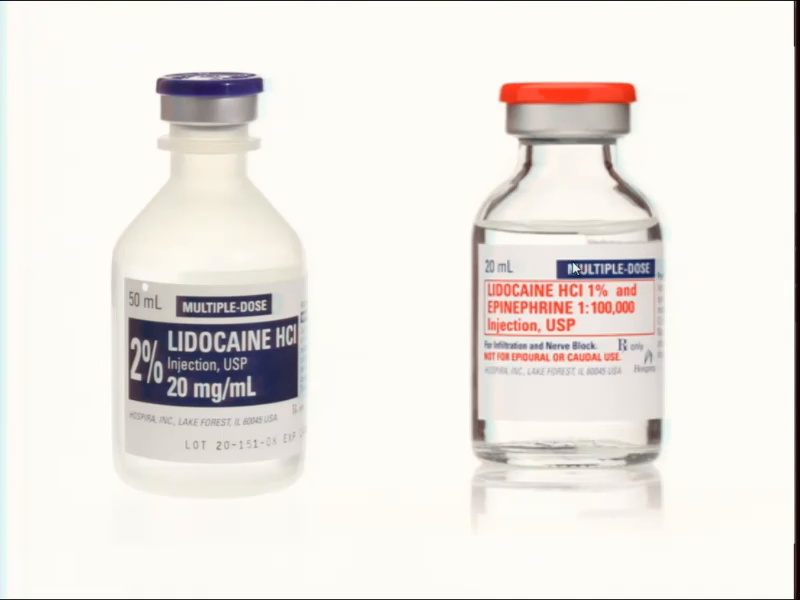

Okay, anyways. Our next consideration is analgesia. I can’t use some of the methods because of where I live, but plenty of grinders can and do. The gold standard is infiltration of lidocaine. Because a lot of procedures we do are in distal areas with poor circulation we use 2% lidocaine without epinephrine. Epinephrine is great in other areas because it constricts blood flow and this keeps the lidocaine in the area longer and it actually decreases bleeding. So like in fingers and ears, though, it can restrict blood flow enough to cause necrosis.

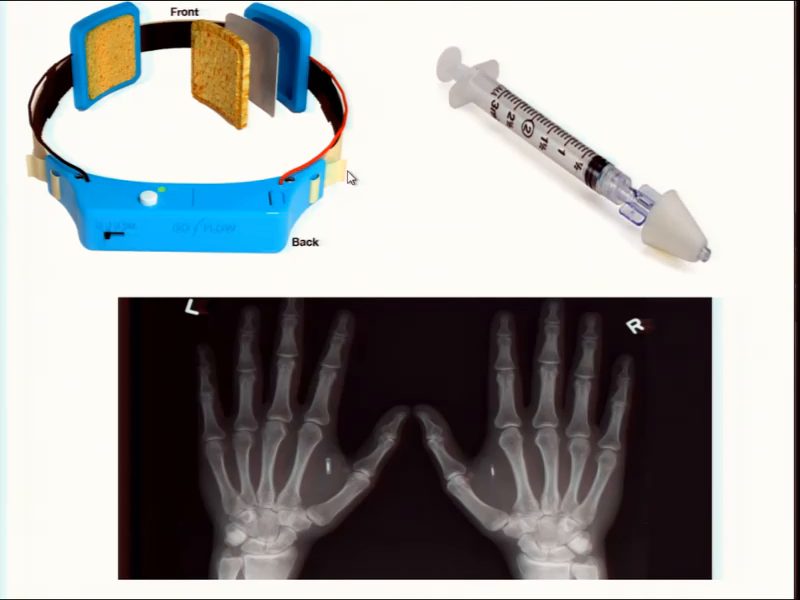

So most grinders are using a technique called a flexor tendon sheath nerve block. That’s where you take a 25 gauge needle and you insert it at about 45 degrees just distal to the palmar crease. This blocks pain throughout the entire finger for as long as an hour and a half.

In places where we can’t use infiltration, people usually opt for a topical lidocaine gel. A 5% gel applied for an hour and a half can provide a degree of analgesia as well. I feel personally that this method takes too long and people still complain of pain. This is an issue in medicine as well. Few people like getting stuck with an IV. There is a product called EMLA Cream which can be applied beforehand to numb the site. The problem, though, is it takes so long to be effective physicians seldom even bother with it. Some kids sometimes get it but that’s about it.

So we’ve been trialing a method of administration called iontopheresis. Iontopheresis uses 120 milliamps to actively push lidocaine through the skin. Using iontopheresis we’ve gotten far better control of pain in as little as thirty minutes, you know. And this is something I’ve never heard of actually being used in the medical field.

So once again you know, are we competent? Yeah, we’re using the same methods—the same safe methods—that you’d find in a hospital setting. And are we knowledgeable? Yeah. We’re actually pushing beyond. Were innovating at this point, you know.

In terms of controlling bleeding, we control bleeding with tourniquets. Did you know first aid kits don’t even come with tourniquets anymore? The improper use of a tourniquet can lead to some really serious problems. These problems are usually because of either too much pressure or leaving them on for too long. For a procedure like a magnet, though, we don’t have to worry about pressure if we use a product intended for fingers. Devices like T-RINGs. They apply less force than a traditional tourniquet, and they let us work without blood to obstruct our view.

In terms of time, you don’t even get a change in your lab values indicating muscle damage has occurred until about the thirty-minute mark. And two hours is considered the point at which lasting damage starts to occur. Most procedures we do take maybe ten minutes, tops. And for more invasive procedures we do use surgical tourniquet. This approach requires a lot more specialized knowledge. We had to pay attention to details like the proper limb occlusion pressure and we have to be really careful about recording time. But I’m to skip over those details pretty much in the name of brevity because… But I don’t want you to confuse this admission as being due to incompetence or ignorance.

So where are we? We have a disinfected procedure area and sterile tools. We have a clean procedure site and clean hands. We’re pain free. Bleeding’s controlled, so we must be ready to start cutting.

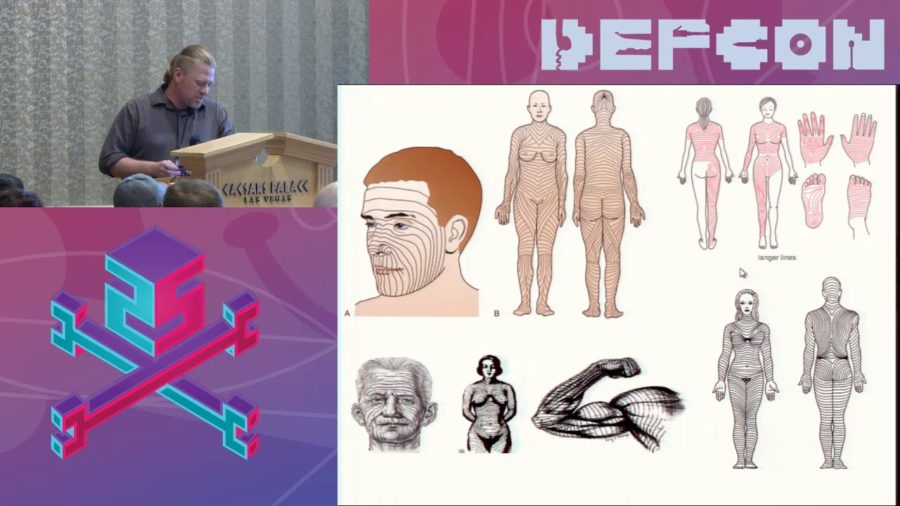

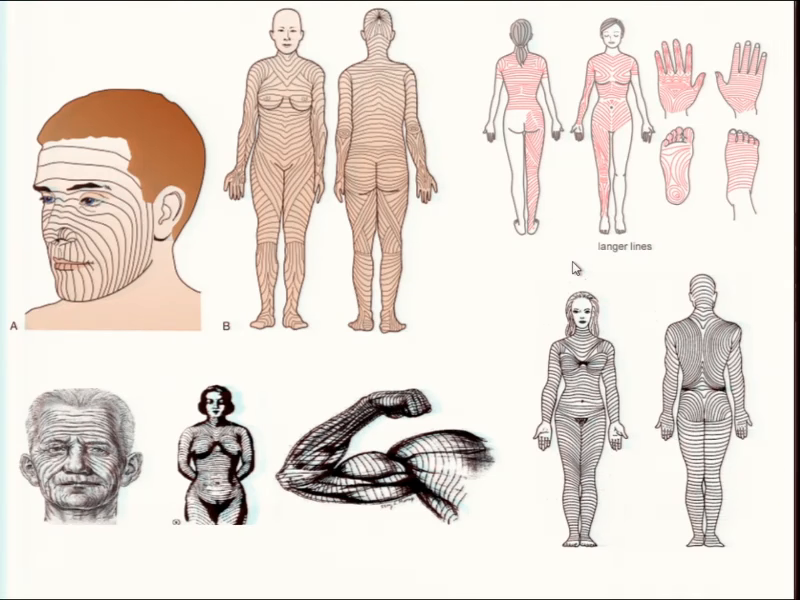

Where do we cut? The priority of course is avoiding blood vessels and nerves. Then we worry about trying to minimize scarring. Skin has a grain, kinda like how wood does. The collagen fibers are naturally oriented in one direction called Langer’s lines. You get these really cool topological maps showing the direction of collagen.

You also have to take into consideration the direction of maximum skin tension, okay. This is a different set of anatomical skin lines called Kraissl’s lines. Plastic surgeons usually place incisions that are parallel to relaxed skin tension lines. Those are known as Borges lines, unless there’s a nearby natural wrinkle that would hide your incision instead. So basically, choosing the incision site to maximize aesthetics is more difficult than you would think.

So I switched out a Northstar implant for my friend Bird. She’s in the back right here. When we switched out the Northstar— Oh, by the way she really digs scars anyways, and she explicitly gave me the okay to try a different approach. Anyway, so I incized parallel to Langer’s lines, hoping to minimize the scarring on her hand. And I didn’t really account for the skin tension on the skin. So when it was healing you know, whenever she moved her hand around, it was pulling on the incision site.

So basically, because I didn’t account for the tension on the skin, it was constantly pulling and I was really disappointed because the incision ended up scarring worse. So if you can see right here, along this line this is the original incision point right here. And right here’s the incision that I made when I was switching them out. I mean, the original one is about a year of healing further along than this one, but still I think that it’s going to end up being a bigger scar overall. So it’s kinda one of these things where we’re still playing with it and trying to figure out the best approaches. But it’s not something that I would say we’re ignorant about.

Once again, are we ignoring or incompetent in this area? I’d say it’s a wash. I’ve seen beautiful work done by both plastic surgeons and body modification artists. At the BDYHAX conference, I got to hang out Russ Foxx. He’s like a god in the body mod community. His work’s beautiful and I’ll be the first to admit I’m not at his level of competency. I’ve also got to sit through a number procedures performed by one of the top plastic surgeons in the LA area. There’s no way I can do what either of them do. That said, people don’t come to me to make them pretty. What people expect is the safe placement of a safe device, which is something that grinders are competent to provide.

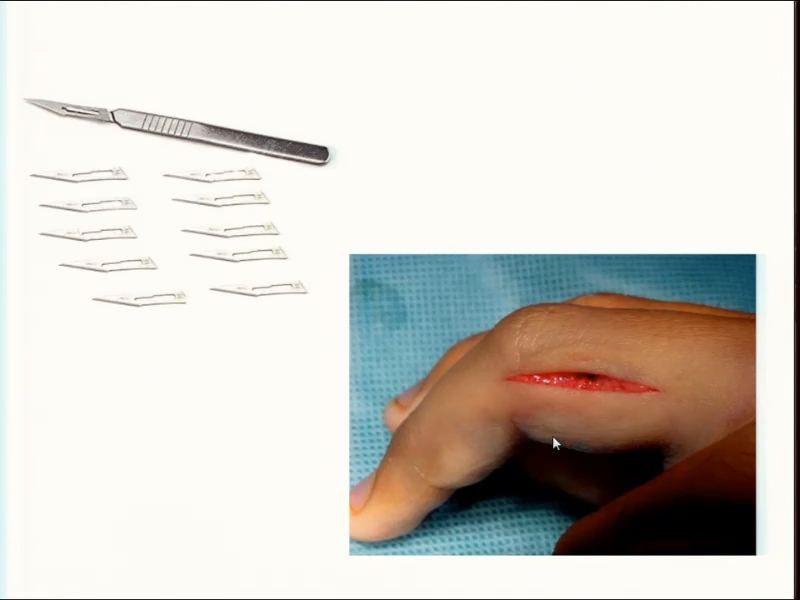

So, in terms incisions. How we make the incision depends on what we’re doing. Objects in glass capsules like tritium fireflies or RFIDs can be placed using an injector. So, for other implants we use a 15 or 11A scalpel blade on a number 3 handle. A scalpel’s held with a pencil grip in the dominant hand, while the non-dominant hand provides tension on the skin. We make the incision slightly larger than the object to be implanted. When you get below the dermis, the connective tissue tears easily.

The artist chooses between blunt or sharp dissection. You can separate connective tissue with a probe, but I found blunt dissection causes more trauma and increases healing time, so usually opt for sharp dissection with a scalpel. Sharp dissection comes with the risk of cutting through an important structure. So if I’m working in an area I’m less familiar with, I like to go with blunt.

The point of separating the tissue’s to create a pocket for the implant to sit in. It’s best to create a pocket that’s somewhat larger than the device you want you want skin laxity. You want enough give in that area so that you can approximate the incision without it being under tension.

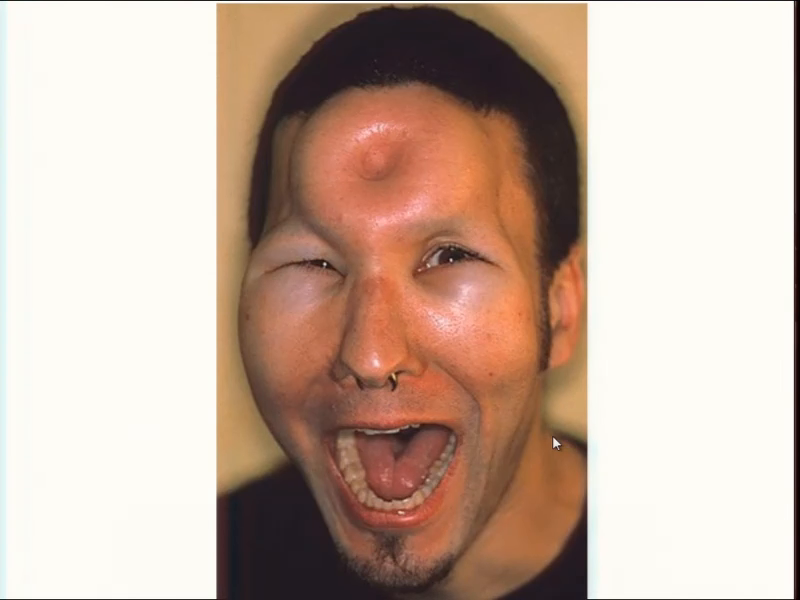

Okay, so bagel head. Are you guys familiar with what this is? Basically a year or two back there was a physician who started posting on the biohack forums. And suggested we a try technique that’s called fluid dissection. It’s like the bagel head thing right here. The idea’s you put fluid under the area under pressure and it creates a pocket for you. So in this case that’s just normal saline that was done with an IV needle, and you fill up the area and you push with your thumb in the middle. Pretty much the saline reabsorbs within I don’t know, six to eight hours.

Anyways, so his idea was that we could do like how you do a TB test. And I’ve done this hundreds times as a nurse. When you’re doing a TB test you’re actually doing an intradermal injection. You’re going to go into the skin, do a little injection and it makes a bubble. And his idea was essentially that we could make this big saline fluid pocket that way, and then just cut right into it, slip the magnet in and no problem, you know. I was somewhat critical of it. I recorded a video where I tried out the fluid dissection method three different times in three different areas. And it didn’t work at all.

The weird thing, though, was when I posted what I found, okay. So I went up and I posted what I found. The guy just like, flipped his shit. Despite giving him credit and only posting the video as a direct response to the thread he started he accused me of plagiarizing his work. He swore to never help us again and quit the forums. Why would I plagiarize a technique that doesn’t work, you know? I seriously wonder if it’d worked out if he would have still been upset. I think the real issue may have been an ego bruised by someone with like one fifth of his credentials demonstrating that he’s wrong.

So, closing the incision. We use a non-absorbable suture like polypropylene with a 3/8 curvature reverse cutting needle. I taught a class during Grindfest a few years back on suturing. And the three techniques we practiced were simple interrupted, running sutures, and horizontal mattresses performed with an instrument tie. These types can used for probably 90% of procedures we’re doing, and we’re just not doing anything complicated enough to require a larger repertoire.

The technique’s then removed. We let a small amount of blood out, flushing out the wound. And then we apply pressure for a minute and the bleeding stops. The wound’s then dressed using Steri-Strips. Initial healing takes around three weeks, during which the focus is on controlling inflammation using ice and ibuprophen. Sutures are pulled sometime between day three and seven, after which Steri-Strips are kept on to prevent the site from reopening. Collagen fibers reinforce the wound after a month, although wound maturation and remodeling can take more than a year. Again for the sake of brevity I’m omitting a lot of information that I would consider essential.

As much focus as we’ve put into safe implantation, the insertion of the device is actually the simple part. It’d be easy to stand here for another hour speaking exclusively about biocompatibility. The community is constantly brainstorming new types of coatings and ways to apply them. Medical devices like peacemakers are usually coated in either a biocompatible alloy like titanium nitride, or a polymer like parylene. The simplest biohacks don’t require even these.

When injectable RFIDs were first being marketed I was concerned because they’re encapsulated in glass. My concern, and the concern of probably a lot of people, is that if the glass breaks in your body it seems like it could cause harm. So I was involved in the testing of this idea. And what we found is it takes so much force to break these things that if it happens, the glass is the least of your worries. I mean sure it’ll break if you drive over your hand, right.

Another concern I’ve seen pop up over over and over is research indicating that RFID implants can cause tumors. So there are journal articles about this. Rats and mice, particularly the types used in labs, are particularly prone to tumors. These studies have shown that as many as 10% the rats developed a harmless tumor near the RFID capsule. They’re called post-injection sarcomas. What you don’t realize is these sarcomas occur in [?] models regardless of whether the RFID is there or not. It happens in cats too, okay. It has something to do with the animal’s inability to handle oxidative stress. Cats just sometimes get tumors if you poke them with a needle. Its like acetaminophen. What’s poison to a cat isn’t necessarily a poison to us.

Dogs on the other hand, they seldom ever get post-injection sarcomas. I only found one case study ever of a dog they found this type of tumor in. We’ve hundreds of thousands of RFIDs in dogs. These studies, they just can’t be applied to human applications. I’ve never heard or seen of an RFID being rejected, breaking inside of someone, or causing a tumor to form.

Most projects, however, they don’t fit in glass. So early work like the Circadia used silicone. It’s a material that’s been safely used by the body mod community for years. It has its disadvantages though, and we’ve almost entirely replaced it with titanium nitride and parylene, the same coatings as biomedical devices.

I subscribe to a journal that discusses biocoatings, and I came across an article talking about a method developed which could apply a layer of diamond. When I contacted the guy responsible for the research, he helped me produce a batch of neodymium iron boron magnets coated in diamond. Out of the ten I’ve implanted only two have had problems. We haven’t yet determined if these problems were related to a defect in manufacturing, a problem with diamond coatings, or simply because of events related to healing. But this is another example of the biohacking community not only matching the diligence required in medical devices but striving to exceed them.

There are many considerations that go into making implants I’m not even qualified to address. I know there’s a lot of work regarding appropriate batteries. It’s obvious something equivalent to a Samsung bursting into flames under the skin could be lethal. But there are more subtle issues like outgassing.

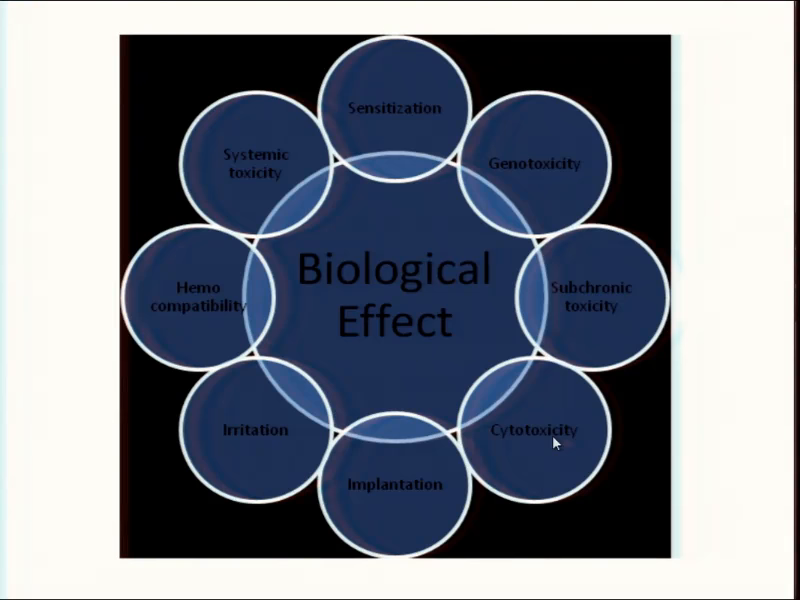

Bottom line is we don’t expect our implants to fail but we have to engineer them so that if they do they do so harmlessly. And we have to perform tests to determine if we succeeded in making them safe. For devices to be approved by the FDA you need ISO 109903[sic] certification. This requires cytotoxicity testing like direct contact tests or agar diffusion tests. Sensitization assays are used to determine whether the material’s going to cause hypersensitivity or an allergic reaction.

Basically with these tests, we have no obligation to do these tests. We’re not in any way obligated by the FDA or anyone to essentially be performing these tests and we still are. I mean, if you look at what Grindhouse has done, they’ve done these cytotoxicity test. If you look at some of the stuff we’ve done with the different coatings and [inaudible] stuff, I mean we’re doing the majority of tests with I think— What we’re missing, pretty much nobody does multi-generational tests to see if you know, four generations down the road there’s going to be problems. But I mean with the majority of materials we’re working with it’s already been done, with the exact same materials. And yet we’re still repeating these tests just because in the community were just so… We put so much emphasis on trying to create a safe product—you do this the right way, okay.

So despite how simple something like a magnet implant seems to be, it requires a lot of work and a lot of research. This is work grinders are doing and skills we’re learning. Are we competent? Absolutely. There may be a safer and better way to do these things but if there is I’m willing to bet grinders will be amongst the first to put them into practice.

Are we ignorant? No. We study and practice our craft without being blinded by ego.

Should we wait for those who consider themselves to be professionals to give us their blessing? Look, no surgeon’s going to be willing to do the things we’re doing. Medicine returns the body to the state we consider normal. It’s not the pursuit of becoming more than human.

The body modification community is similarly unsuitable. Biohacking’s rooted in cooperation and collaboration. There are great guys like Hayworth and Russ Foxx but body modification in general is poisoned by an unwillingness to collaborate, okay. This is fine when we’re talking about nipple piercings but grinders are already working on designs for brain-computer interfacing, you know. I want the skills to place a multi-electrode array and expand on the type of work Kevin Warwick did fifteen years ago. I don’t know any physicians willing, or body modification artists capable, of doing this. There are no masters, there are no professionals. If we’re not skilled enough the only option is to become better at what we do.

So why is it I’m convinced someone’s going to die? In 2011 there was a BMJ case report titled Body piercing with fatal consequences. A man in his fifties died from a mesenteric infarct. What that is is basically he had a belly button piercing and it migrated inward, cut off blood flow. I’ve seen about three of these in my career. What happens is they have some kind of GI upset, they open them up for exploratory, and their entire gut is already just grey and dead and there’s nothing to do. You sew them back up and you tell them, “Say goodbye to your family.” Within a day they’re vomiting feces and then they die. It’s terrible, okay.

And obviously this is not an exception, you know. There are case after case of people dying from all kinds of things with piercings— But it’s not just piercings. That’s not the only thing that scares me. I mean, I’m convinced someone is going to die because there are between two and four deaths a year on average in the US from people shaking vending machines. People take every precaution or are about meticulous aftercare— I mean, it’s still a risk, man. Someday, it’s a numbers game and somebody’s going to die.

The problem with this is that there’s going to be that backlash from the first inevitable death, right. So far the media’s been kind to us. Everything we do. I mean like, people have been doing piercings for…into antiquity. And yet we put a stupid magnet in and it’s like, They’re cyborgs, man! They’re innovating!” No no no, we’re not really doing that amazing stuff. But you know, the way they’re pitching is we’re doing this amazing—, or we’re doing something different than everyone else.

The problem with that is when somebody dies, that’s just going to blow up in our face. I mean, the way it’s going to work is that same sensationalism that blew it up as a hundred-fold of us doing these things, it’s also going to be you know, “Oh my god, these dangerous people doing these dangerous things.”

And we know what they’re going to say about it. What’s going to be is they’re going to say we’re ignorant, and we should’ve looked into the risks of what we’re doing. They’re going to say we’ll all get sepsis and flesh-eating bacteria. They’re going to assume we’re incompetent and they’ll say procedures like this should be left to someone else. Someone who has the knowledge and competency to do it right.

I mean, come on guys. It goes like this. Look, we drive cars around, right? And we think it’s okay even though look at the number of deaths that occur from cars. No one’s saying we’re going to stop driving because it’s too dangerous, right. Beyond that, even beyond necessity, there’s…you know, people smoke. He smokes cigarettes, it’s killing this many people, and yet it’s acceptable in society. We smoke cigarettes.

But what we’re doing, it’s also risky. But you know what? It’s a risk we’re taking because we believe in it. We’re try to create a future, you know. We’re doing something that’s meaningful. And so I don’t have anything to say about really the backlash when the first grinder dies. We’re screwed. But, I’ll tell you what I do know. I do know that that person that first dies, they died doing something they believe in. They died doing something that they researched and knew the risks, and they did it anyways. And they died in a way that they felt was meaningful.

Audience member: Damn straight.

Tibbetts: Yeah. So that’s all I gotta say. Thank you.