Thank you, Sophie. And thanks to all of you. I’m really excited to be here today, to have a chance to speak with you. I came into doing work in an antidisciplinary space more or less by accident. Back when I was applying to university, the schools would send out these books talking about the different programs they offered and what each program was like. And for some reason I never read any of those books. I just applied to engineering school because I thought, “Oh, you know I like to make things, and engineering school’s where you make things.”

But it turns out that there’s a lot of math that you have to learn in engineering school. And I was never that good at math. So I wound up leaving engineering school and getting a degree in interdisciplinary studies.

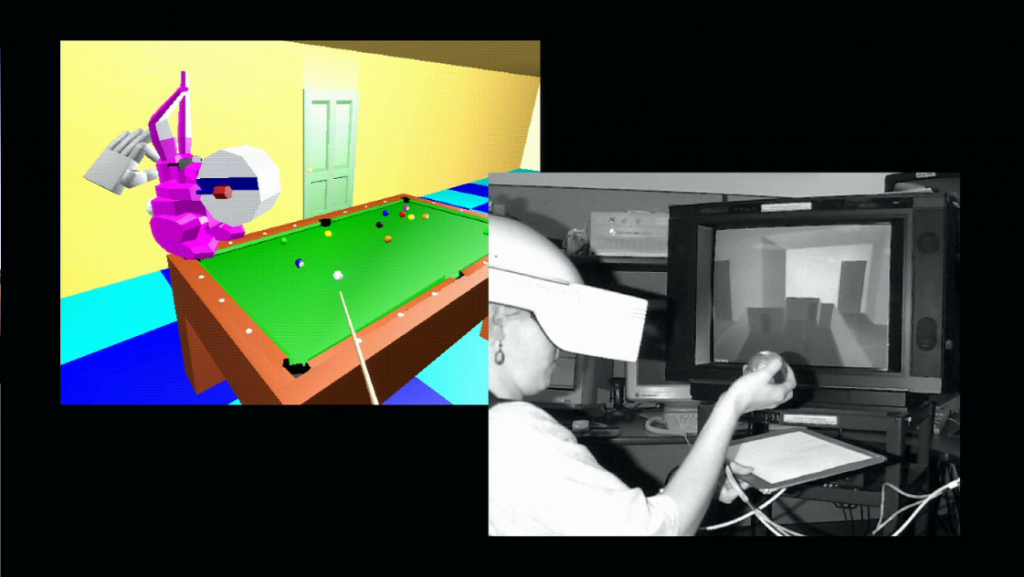

But before I left the engineering school, I found this team that was working on virtual reality. This is back in 1995, and so the graphics aren’t quite as advanced as some of the things that you might see today. But we had a team of I guess…let’s see, computer scientists, psychologists, mechanical engineers… What else did we have? We had a neurosurgeon. So all of these people brought together in a team to solve a problem that didn’t really fit into an existing discipline.

And one of the things that I realized when I was working on this team is that when you’re working in an antidisciplinary space, it can be very polarizing. There are a lot of people who will tell you that what you’re doing is a total waste of time. And then there are other people that will tell you that what you’re doing is totally amazing. And I was always thought this was interesting, that there weren’t very many people in between. That people always thought oh, it’s amazing, or it’s a waste of time.

And so we were based in the computer science department at the University of Virginia, and most of the people in that department working on problems that were solidly in the domain of traditional computer science. Things like supercomputing, algorithms, databases, these kinds of topics. And there were some people who didn’t really think that considering how people should interact with computers was necessarily—you know, that that kind of thing belonged in the context of a computer science department. Likewise, people in the art department didn’t really think that what we were doing was art, and so on.

And so one of the things that I really took away from this experience, my first experience in an antidisciplinary team, was that if you’re working in a space that doesn’t fit within a traditional discipline, you really have to blaze your own trail. You really have to decide what you think the right path is for your work. And sometimes it can be a bit of a stretch to shoehorn what you’re doing into a traditional discipline.

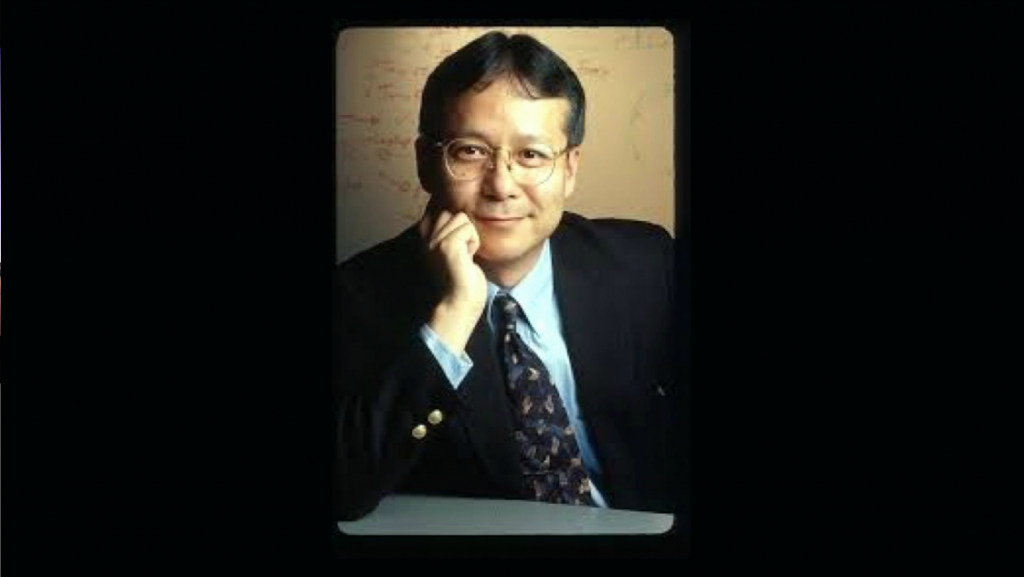

Here’s an example of that. This is a project called “inTouch.” This is what you could describe as a a haptic telephone. It’s a device that communicates with the sense of touch over a distance. And the way it does that is it has three wooden rollers in each of these units. And whenever one of those rollers rotates, the same roller in the opposite unit rotates in the exact same way. So the metaphor is like a physical object that exists in two places. And so when two people touch that, it feels like they’re touching the same object even though they’re touching two objects that are separated by space. This was a project out of a professor Hiroshi Ishii’s group at the MIT media lab. And the first time I saw this, it was at a conference on computer graphics. Now, obviously this project has nothing to do with computer graphics at all. But that was the closest fit in terms of interaction, in terms of trying to rethink how people would relate to technology. So when I saw this project I said who did this? Who’s the professor in charge of this? I have to work with this person. And that’s how I came to to be at the MIT Media Lab. I did a PhD with Professor Ishii.

The Media Lab is essentially a a big experiment, and the question is if you put a bunch of people that come from a bunch of different backgrounds in the same space and let them work on whatever they want, what happens? And the expectation was that 90% of the projects that came out of the Media Lab would be a failure. But the hope was that 10% of the projects would have a dramatic and disruptive impact on the world.

And one of the interesting things about being a student at the MIT Media Lab was that if you’re working in this space that’s outside of a clearly-defined discipline, then traditional methods of teaching don’t really work, where you sort of put everyone in a classroom and teach them the the basics of an established discipline. So what happened instead there was that students would teach each other. And it was all project-based learning. So the idea is that each student would come into the Lab with a set of skills that they were very proficient in, and they would be very eager to share their skills with all of the other students because they knew that when the time came when they needed to learn a different skill from another student, they would help them in return. And so this very informal project-based skill-sharing of skills is an approach that seems to work really well when you’re working in an antidisciplinary space.

This is professor Ishii, and his group is called the Tangible Media Group, and the idea behind this group is to take our interactions with technology off of screens and bring them into the physical world, taking advantage of the sense of touch. And this is more than just a traditional touch screen. It’s not really about that at all. It’s about physical objects in the world that have embedded sensors and actuation that allow them to represent and control information that’s inside the computer.

I’m going to show you a variety of projects during this presentation, and the thing that brings all of these projects together is that they all required uniting a bunch of different disciplines, or working between disciplines, in order to make them real.

This first example is called curlybot. This is a robot that records and plays back physical motion. It’s a children’s toy. The idea is that it’s got one button on it, and you push that button and you record a motion into the robot. And then as you push the button again, the robot plays that motion back over and over again. So this is the way to teach kids a lot of complex mathematical and geometrical concepts through play. Lego wound up licensing this, and I think they’re still making and still selling it as a toy. But to bring curlybot into reality, there were a bunch of different fields that that had to come together. So, experts in children’s learning, mechanical engineers, electronic engineers, product designers, software developers, and so on. So, all of these different disciplines coming together to build a project that didn’t really fit into any one particular discipline, but still had a pretty significant impact in terms of how we thought about childrens’ play.

Here’s another project. This is called bioLogic. This is a a new type of fabric that has these little vents. And each of these events has living bacteria inside. And when you start to sweat, these bacteria respond by opening up those vents to give your body more ventilation. So here bringing together the fields of synthetic biology, material science, and fashion to create something that no one in any one of those particular fields could have thought of or brought to fruition as a project.

One of the funny things about the Media Lab is that most people agree that 90% of the projects there are failures and only 10% are a huge success. But no one really agrees on which 10% are the ones that are successful. And so I think this really reinforces the fact that if you’re working in and interdisciplinary space, this feeling of not necessarily belonging that Sarah mentioned really holds true. That you don’t really know if you’re doing the right thing. You don’t really know if you’re on the right path. You have to just kind of trust your gut, because no matter what you do some people are going to say that what you’re working on is amazing and others are going to say that it’s a waste of time.

So that the type of education you get at the MIT Media Lab is very general. You learn a little bit about a lot of different things. What that means is that when you come out of the Media Lab, you’re not necessarily inclined to work at a company where what they’re looking for is someone who’s deeply specialized and highly skilled in a particular very precisely-defined area. And so a lot of people wind up starting their own companies when they come out of the Media Lab.

I wound up doing that. I started Patten Studio almost ten years ago. I’ll tell you more about what we do later on in the talk. But shortly after I started Patten Studio, I met this guy, Al Attara. Al owns a building in downtown Brooklyn that he rents out to artists. I visited Al together with a friend Mitch Joachim, who was a fellow student with me in the MIT Media Lab. And we wound up renting the top floor of Al’s building.

When we got there, it looked like this. Total mess, and as soon as I saw this I said, “You know, I have to move here. I have to be a part of this building.” There was just a creative energy there that I had never experienced anywhere else. And both Mitch and I were missing the interdisciplinary interaction, the diversity of thought that we had experienced as students at MIT. And so we decided to try to recreate that as much as possible, but outside of an academic context. We wanted to create something like that where where people were doing creative work, something that’s made up of for-profit businesses that are pushing creative work out into the world.

And this is what it looks like today. We have everything here ranging from a synthetic biology lab. This is Genspace, the first synthetic biology lab that was open to the public in the United States. All the way to architects, furniture designers, costume and set designers, people building musical instruments, people working in structural engineering. And so the premise is very similar to the Media Lab in the sense of what happens when you put all of these people together.

And Al, our landlord, is a junk collector. But he’s a junk collector with amazing taste. And so when you walk around this building, it can be an incredible stimulus for creative thoughts. I thought I’d give you a quick tour of what this building is like. Here a few things you might see as you walk around. This is an antique animal from a merry-go-round in New York City. A box full of mannequin arms. An antique wheelchair. I’m not going to tell you what this is for, but it involves handcuffs. Use your imagination.

So this turns out to be a space that whatever kind of random object you need, it’s probably there somewhere. And it’s a an incredible place to to do creative work. I’ll show you a couple of projects that have come out of Patten Studio and our collaborators within this space.

This one’s called Patterned by Nature. It’s a thirty meter-long liquid crystal ribbon display that is permanently installed at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh in the United States. It shows these abstract visualizations of different scientific phenomena that repeat themselves on different scales. So going back to Subodh’s talk, this is a visualization of the idea that he talked about, that you see these patterns that repeat themselves in different scales in nature. It uses 3,600 different liquid crystal tiles, and each of these pixels is about twelve centimeters on a side. So, the technology is very similar to what might we might see in the display on a laptop, but what’s different is the physical scale and the shape. And that scale really forces you to interact with it in a totally different way.

Now the thing that I think is really interesting about this project is the group of people that came together to make it real. Four different companies, Plebeian Design and Sosolimited based in Boston, together with Hypersonic and Patten Studio based in New York. And each of those companies brought a different set of skills ranging from the structural engineering, to the the graphics, to the electronics and software. And all of these pieces needed to come together to make a project like this real. And so I think this really highlights the interdependence that’s often there in the context of antidisciplinary work, where you often need to draw from deep wells of knowledge in different disciplines that are well established, and bring them into an unfamiliar space. And doing that requires these collaborative teams. And everyone on that collaborative team is dependent on everyone else.

The next project I wanted to show you is called Thumbles, and this is a rethinking of what a tabletop interface with the computer might look like. So here, instead of using a touchscreen we have these little physical robots that drive around on a tabletop that serve as controls for the different things are doing on the screen. This is a prototype video-editing application, and all of the things that we’re manipulating. So here we’re changing audio levels. You’ve got the left and right channels of audio. And you can reach in and split those channels apart and manipulate them independently. Or you can gang them together and manipulate them as one unit.

So the robots are constantly reconfiguring themselves based on what you’re asking the system to do. So you get this tactile object that you’re holding, which is a fundamentally different experience than touching a dial on touchscreen. We also think that this kind of system has a lot of applications in gaming, to make gaming a much more social and richer experience in terms of interactivity.

Here’s an idea of how this may be used for a scientific problem. [~1:10 of video above] Here the question is protein folding. How can you figure out the natural shape that a protein has in space. And the idea’s that you can attach these robots to different points on the protein and twist it around. And as you’re doing that the system is monitoring what you’re doing, and if it notices that you’re making a fold that doesn’t make any sense, then you’ll feel the robot pulling against you. So, essentially the system is making these microscopic, essentially mathematical forces behave as real physical forces that you can feel pulling against you.

We built a second version of the system that uses these smaller pucks. Each one’s a little robot; they’re about five centimeters in diameter.

And here’s another vision of how this idea might be applied to data visualization. [Slide/video not visible] Here we’ve got a multidimensional data set. And what you can do is you can attach these little robots to different points in that data set and use those points as physical handles to really wrestle with the data. And when you’re wrestling with the data, essentially what you’re doing is solving a complex system of linear equations, but it doesn’t feel like that. It feels like you’re wrestling with a mechanical system. And the same concept holds true that you’re feeling these mathematical forces as physical forces that are pushing against your hands as you interact with this data.

This project is called SenseScape. This is a piece that we did for Intel at the Consumer Electronics Show earlier this year. We used a variety of Intel sensing technologies ranging from their RealSense cameras, to their Curie wearable, to their Galileo IoT boards to create this experience that you could interact with in a variety of different ways. There’s this aquatic scene that unfolds in front of you with thousands of flocking fish that are responding to your motions. And there’s also a component where you can pluck these strings that interact with musical elements of the composition as well.

And so to wrap this all up, I’d say that what differentiates work in an antidisciplinary space from work inside a traditional discipline is that when you’re working inside a traditional discipline, you have a lot of feedback from that discipline about what problems are interesting problems worth solving, and what constitutes actually solving those problems, And what are the accepted set of techniques that are valid ways to attack those problems. And when you’re working in an antidisciplinary space, you don’t have those things. You have to make them up as you go along. And so I think that the challenge is being able to to do that kind of work without the feedback from people, to really know if you’re on the right track or not.

But the magic of working in an antidisciplinary space is that I think you have a much greater opportunity to impact the world in your own unique, powerful way. And if you look back, say over the last hundred years or so, at a lot of the disruptive innovations that have really impacted our lives as a whole, a lot of them have come from work that has existed at least initially in this sort of antidisciplinary space.

Thanks so much.

Sophie Lamparter: Thank you so much James. One question maybe, to wrap this up. Because you’re doing all this work, and you have all these different collaborators from art, to scientists, researchers. So, in your vision, how are we going to interact with the digital world ten years from now, or longer?

James Patten: Well, I’m really excited about where the fields of architecture, electronics, and interaction come together. I’m really excited about the idea that those different fields are all going to become the same thing. And that now we have these devices in our pockets that are kind of our portable intelligent surface that we carry around through these buildings that aren’t particularly intelligent. And so I really believe that the boundary between those two worlds is going to disappear, and that we’ll be surrounded by intelligent surfaces. And we won’t really think about computers and interfaces and this sort of thing anymore than a fish thinks about the water, because it’ll just be something that’s ubiquitous and all the way around us. So, I think that’s where things are headed, and I’m really excited about, you know, there are a lot of different approaches that people are taking to get in that direction, and I’m really excited to see where it winds up.

Lamparter: Great. Yeah, and as I said before, if you can visit Sarah in her office, if you go to New York try to get in touch with James or Jen, who is also here, his collaborator. It’s really a fascinating seven floors of, I don’t know, a hundred people and a hundred crazy ideas. Something like that. Thank you so much, James.

Further Reference

Enter the Anti-Disciplinary Space session details at the Lift16 site.

Citations

- Evidence and Speculation: Reimagining Approaches to Architecture and Research within the Paediatric Hospital

- Facilitating epistemic fluency through design thinking: a strategy for the broader application of studio pedagogy within higher education

- State of the Art in Digital Media and Applications, “Collaboration on Digital Media”