Introducer: Hi, everyone. Welcome back. My name’s Ben. I’m from Webstock. I’ll just be taking you through the next session doing a few intros and so on. It’s great to have you all here. Hope you enjoyed your lunch.

Next up, it gives us really great pleasure to introduce Erin Kissane. She’s a regular on A List Apart. She’s in fact a former editor of A List Apart. She’s the co-founder of Contents Magazine. She’s contributed to many books, and her latest is called The Elements of Content Strategy. She’s come a very long way to be with us today, all the way from Brooklyn. So please give her a very warm Webstock welcome.

Erin Kissane: Hello. One other thing I wanted to mention. I’m also the lead content strategist at Brain Traffic. We are a consultancy who does exclusively content strategy, and I wanted to mention that as well so Kristina Halvorson, who is my boss, doesn’t strike me dead from afar.

It’s so good to be here today. Thank you so much to our organizers for making this such an extraordinary experience. And thank you for inviting me here. It’s so good to be in this beautiful country and meet all of you.

I’m here to talk about systems, and the very first thing I want to do is make a confession, which is that my title, “Little Big Systems” is actually taken from a video game that some of you may know called Little Big Planet. This little guy is Sackboy. He’s the protagonist of Little Big Planet. As you can see, he’s sort of knitted and has buttons for eyes and kind of a zipper. The whole world of that video game is much the same way. Everything looks as though it’s been stitched together or made of clay or cardboard or some kind of handmade playful material. That really changes the feel of the game, even though it’s essentially digital images projected onto 3D models inside a video game. So Sackboy has been with me all the way through.

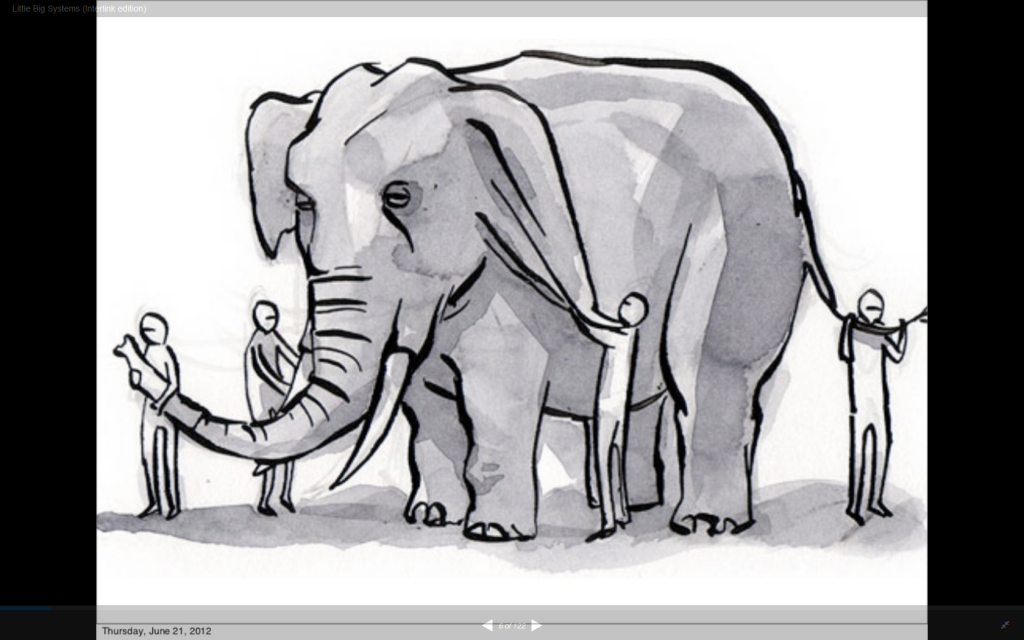

I’m here to talk about making systems. But before I can talk about making systems, I need to talk about an elephant.

Some of you may recognize this. This is Kevin Cornell’s illustration from A List Apart magazine. It ran in [2008] alongside Kristina Halvorson’s The Discipline of Content Strategy, and of course what it’s referring to is the encounter of four guys who run into an elephant in the dark, as you do, and are all sort of reaching for the part of the elephant that’s closest to them and trying to figure out what sort of creature they’ve encountered.

So one touches the leg and says, “I think it’s a tree.” And the other guy’s got the tail and he’s sure it’s a snake. And somebody else has the ear and says, “I think it’s actually a palm tree?” So this illustration of the trouble defining content strategy was so dead on that the elephant has become our sort of informal symbol as a practice. We have our own animal. It shows up in a variety of places, including the logo of Contents Magazine.

The thing about this trouble defining what exactly it is that content strategists do, it’s not that interesting a dispute on its own. I mean, the conversation might be interesting, but I mostly leave that sort of thing alone. Except for one problem, which is that Mars needs content strategists.

One of the troubles with making new content strategists is that they don’t grow from cabbages. We have to find them. Find people from allied fields, find people with the right backgrounds, from editorial work or library science or information science, and bring them into the fold, explain this is what content strategy is shaping up to be and this is your transition in. And it’s been a little bit tricky because content strategy strikes a lot of people as weird. And I have a theory. I think the reason it seems weird to people is that it’s actually a form of system design.

What that means is we don’t make things in the same way that for instance an editor might make a magazine or a book or a newspaper or…all of us, designers make specific kinds of artifacts. We’re used to thinking about the things we produce. In content strategy we don’t really make things, we make systems that make things.

So, as I was thinking about how we could better bring in some of these people from the sort of artifact-producing mind to how they might make systems (in our case content strategy systems) I became aware that this was actually kind of an issue for people not just in my field but also in design and development, a lot of interconnected fields within web design and now app design, and the broader electronic design field. Part of this has to do, I think, with the resurgence in interest in craft, specifically in the values of craft. What I mean by that is, when we think of the craftsman, we think not just of excellence but of mastery. Not just of quality or high quality, but of exquisite quality, of true excellence in the thing itself. And also a human scale. So mastery, excellence, and human scale are things that I think have been coming back into our own world of web makers in really interesting ways, many of which are coming up in the talks we’re having here at Webstock.

That’s all well and good, but I’m noticing that many of my younger friends and colleagues are confining themselves to smaller and smaller projects, I think in part because this is very attractive, this sort of craftsman’s work. It’s satisfying. It’s human. And if you work on only very small things that have a very defined scope, it’s easier to see how that translates. But the problem with that is that we miss the opportunity to bring those values and practices of craft to larger projects.

Before I go further I want to say, what is this “systems” thing about, what is systems design? For me, all big projects are systems. In fact the OED has a definition, a system is any “set or assemblage of things connected, associated, or interdependent, so as to form a complex unity.” So really anything sufficiently tricky, that is not just A to B to C, is a system. Now why do we care about that?

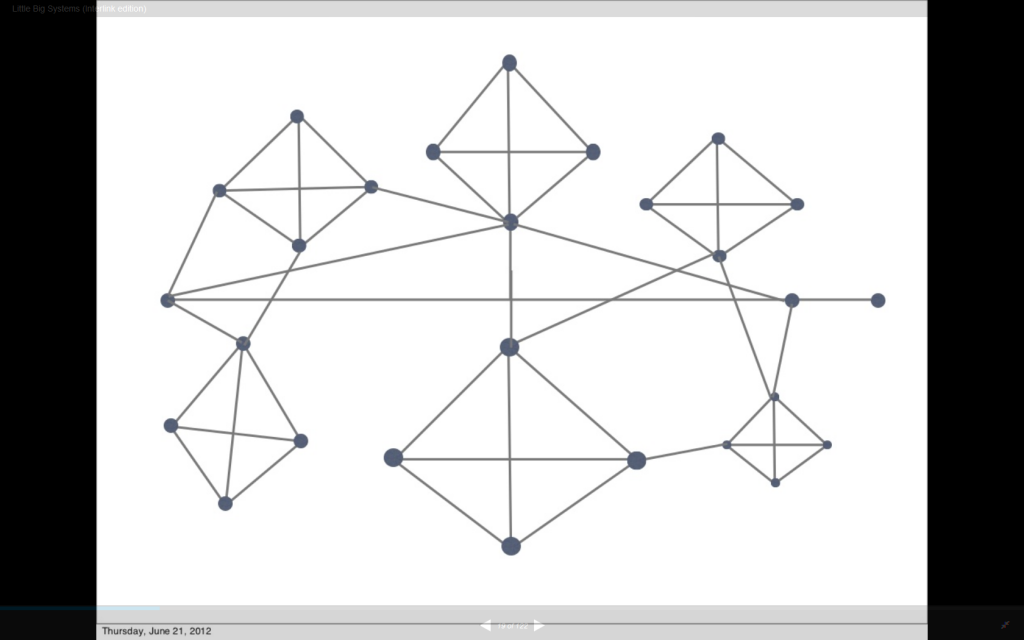

If we’ve got a really simple design problem, say you want to get from A to B but you’ve got to deal with C along the way, that’s quite a simple process that’s really bounded. This is a system design problem:

The reason that it’s different is that you can see there are all these sort of interdependent subsets, so you can’t just step through and say, “I’m going to go from A to B to C to D,” because all of these things are interconnected. You can’t just divide this up into smaller pieces, which is often our first impulse when we see a complex problem, and go through them in a linear way because they’re all interwingled.

The architect and wonderful design thinker Christopher Alexander (some of you will know him from A Pattern Language) writes about system design as a question of adjusting and in fact eliminating “bad fit.” Here’s what he means by that. If you have a system design problem, if you have a series of knotty, connected problems, you have to go into one and work on it until nothing mis-fits, until there are no bad fits, until you’ve solved all of these micro-problems. But then you have to go back out and see what your changes have wrought on the larger system. And it’s this iterative process. Then you go into another sub-system and come back out. This is what makes system design different from the simple design problems that we might in some cases prefer to deal with.

So why does that matter? I think the answer is that our industry can’t afford to let these two streams diverge. We can’t let our young designers and developers and writers, who want to be craftsmen, be separate from the stream of people who are working on these really complex, often kind of daunting, intimidating, tricky problems. For me, I’m a content strategist, so most of mine have to do with content systems, but it’s far from limited to that. Any kind of large public design project, any kind of really substantial, even corporate design project involves this sort of system thinking, these system skills.

So what I’ve been wondering for some months is how can we bring the values of craft that we most easily see in small projects to bear on these big tangly problems? And I have a series of five proposals for possible principles we might use to do exactly that.

The first one is that we should return to the artifact. Does anybody know what these are? [From audience: Japanese sweets.] Yes. You get a bag of Japanese sweets at the end of the talk. They’re called wagashi. They are a traditional Japanese sweet served with bitter green tea, matcha. They’re tiny, and they’re quite exquisitely designed. In their most refined form they are entirely made by hand. Not just by hand, but made with special tools, special equipment, and people who have trained and documented their processes for years and years, decades, in fact this goes back centuries, to make a very specific kind of artifact.

This system is designed to produce one kind of thing. This is the sort of wagashi that you get during cherry blossom season; it’s the sakura. They’re quite different from the high summer wagashi, or the fall wagashi. It’s a very complex system. But it’s tuned to produce a single artifact. By artifact I mean a material and a goal brought together. So in this case you’re talking about particular kinds of sweet bean paste and sugar, brought into this particular form through the use of tools and hands.

This system is tuned for one kind of artifact. If you begin with a different artifact, like for instance the Aero bar, you’re going to need a different kind of system, like this Nestlé factory in Dubai.

Photo: Nestlé on Flickr

I think most of us would prefer the workshop to the factory.

So the first principle is that an intimate knowledge of articles is something that we really need if we want to make better systems.

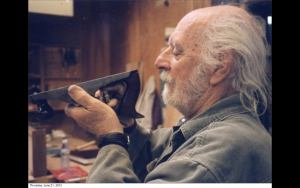

This is a man called James Krenov, and he is well-known for being an extraordinary cabinet maker. He makes—he made (he passed away in 2009) really lovely handmade furniture. He actually started carving when he was six years old. Someone gave him a jackknife and he began making his own toys, and eventually studied in Sweden under the father of Swedish furniture design before striking out on his own in his own tiny workshop.

But he’s also really well-known for being a teacher. He wrote a series of books in which he discusses not only his own processes and the methods he uses for hinges and joints, but also his philosophy of working and his philosophy of understanding what the wood wants to be. That sounds a little woo but he means something quite concrete by this, which is that if you understand the wood that you’re working with, you know which uses it is and isn’t suited to. So if you force onto a piece of wood a bad shape, something that it’s not well-suited to, it may look okay in the beginning, but it’s going to crack later on. You’re actually going to see it physically come apart if you use the wrong materials. And it dishonors the material you work with, so you need to match the right material with the right goal to produce the right artifact.

And all of his systems, all of the tools that he made by hand, all of his workshops, all of his instructions, are designed around that particular kind of artifact. So intimate knowledge of artifacts makes better systems, and better systems produce better artifacts. So always return to the artifact.

These are the Mast Brothers. They make chocolate in a tiny magical chocolate factory in Greenpoint in Brooklyn. They are in fact brothers, and they have this wonderful place that has all of these custom and semi-custom candy-making implements, and it’s all very shiny and brass and it’s wonderful. They’re here as a reminder that many of us make systems that have more than one kind of user. We tend to think about this as our user:

This is the guy in his charming I think Harry Potter costume who eats the candy. He’s our consumer, he’s our end user. And we in the web industry have been learning more and more over the last decade and a half that we must treasure this user. We shouldn’t, for instance, make web sites designed around our org charts. We should design them around our users’ needs. But there’s also this kind of user, which is the maker:

In the content strategy world these are editors, they’re writers, these are the people inside organizations who are actually using the systems we build to make things. And it’s not limited to content strategy. Think about other internal users like customer support and technical support. Anyone inside a company who uses systems, often the systems that we make, to serve that candy-eating consumer.

In the content strategy world, and I think for any of you who’ve used very many CMSes, there’s a common problem. Most content management systems are real bad. This isn’t necessarily their fault. It’s a young industry. We’re early in the development of these tools. But a lot of them are really awful. They’re super clunky. It takes eight steps to do things. You have to implement workarounds. They get between the makers and what they’re trying to do for the user. This points up a problem that I think…when we tend to focus through user-centered design (as we all should) on the need of our users, we forget that if we don’t serve the makers, we’re doing a disservice to the end user as well.

I think something that points this up is the success of WordPress, not just as a blogging system but also as a CMS. There are 71 million WordPress installs. Most of those are individual. Most of them are small-scale, for blogging. But many are actually for what we would consider “enterprise” CMS use. So I think that show that the people who are inside our companies, the maker audience, they have the same needs as the other users. They need simplicity, they need ease, they need things that are intuitive and that don’t get in their way, that are easily configurable. I think this is why we’ve seen WordPress winning against these enormous, extremely expensive, entrenched, frankly horrible to use content management systems that many of us came up with. So what we need to stop doing is making systems that hinder excellence by harming our internal users, our makers. So we need to remember to value both kinds of users.

The next thing that I want to talk about is bread. One of the wonderful things about bread is that you can’t rush it. Bread is going to take the time it’s going to take. It has to rise, it has to bake, it has to cool. If you try to cut it too soon it’s going to fall apart. So I think there’s something of the craft of baking that we can learn from, which is that we need to begin insisting that we work in craftsman’s time.

What I mean by that is not the time of rushing, not the time of compressed project schedules in which we know we know can’t do the job that we want to do, we can’t achieve the excellence that we want because there simply isn’t enough time for the scope. That’s a mis-fit, and also not the kind of diffusion that a lot of big, complex projects come along with. When I’ve spoken to friends and colleagues about why they tend to avoid a lot of big projects, or at least very many at once or in a row, the single most common thing was time. They said either on a big project the scope is so big that you know you can never get down to the details and get them right, and it sort of hurts as a craftsperson to let that go by. The other side is that kind of diffusion. It’s going to be a two-year project, am I still going to be here when it’s done? It’s sort of drawn out, things have moved too slowly, decision processes take too long, and people lose interest. So this is a problem.

And I was thinking about this. I’ve been watching a series of short videos produced by Prada, the fashion house. Prada employs hundreds of craftspeople. They make things literally by hand. All of their couture lines are hand-sewn, hand-cut, and one of these short films is of one of their cutters. This a guy who, from some very expensive pieces of leather, cuts out the shapes that will eventually turn into handbags. I’m not that interested in handbags, frankly, but I do think that there’s something really quite extraordinary about the kind of time that a craftsman like this works in.

The thing about a craftsman’s time is that it’s actually quite efficient. There no wasted motions here, but it’s also not rushed. If it’s rushed, you compromise the material. This is a kind of time that we need to win for ourselves, and the people that we need to work with, to win it from, are these guys, the project managers. So if there’s one thing that I would say about how we can do better to integrate craftsman’s time, a craft sense of time into our work, it’s that we need to love our project managers better.

The first part of that is we need to understand their craft better. It’s not magic what they do, the way that they make scopes and schedules and handle numbers and make those Gantt charts and all of that. It’s complex, but it’s learnable. It’s something that we should all probably know a bit better.

On the other hand, we need to teach them more about our craft, which means that we need a good understanding of the natural pace of our work. And that’s tricky because sometimes if you’re talking about complex projects, you might have a project that doubles in complexity. But the schedule doesn’t just double. You might need three times the amount of time to do it justice. So it’s incumbent on us, whether or not we have actual project managers standing between us and the schedule, to know the natural pace of our work and to say if the complexity level changes either the time is going to change, and it’s going to change by this much, or you are going to see these problems in quality and they’re going to have these effects. So we have to learn to be defenders of our time.

The craftsman’s time in the end is also a lot better to work in. On small projects, you might be able to sprint for two months or four months, or God help us six months, but if you’re working on a two-year project or a three-year project that’s not actually tenable. So that’s the other thing about the craftsman’s time. It’s human and it’s humane, and we deserve to have good, real lives, even as makers of things. So this is what we can learn from the bread.

The fourth principle is to ship small but excellent. This idea of working from large to small has gained a lot of currency recently, I think in part because of 37signals’ work and some of the things Jason Fried’s written about working large to small. What that means is don’t get hung up on the details too soon. Details are important, but unless you’ve dealt with the big design problems with the outline of things, with feature design, it’s not the right time to get into things like labels and colors and pixels and placement and all of that. That’s certainly important. I think most of us have probably been in a conversation or a project where you stopped and worked on details too soon and that means the big stuff doesn’t get taken care of. If you’re working on a systems design project, this is deadly, to do anything but work large to small.

But the flipside is that we need to ship small to large. By that I mean this idea of the Minimum Viable Product that’s been in conversation a lot, thanks to Eric Ries. The minimum viable product can be a lot of things to a lot of people. There are a lot of choices embedded in this simple-seeming notion of what a minimum viable product is. If you want to bring the values of craft to system design, then your minimum viable product has to be something that’s small enough for excellence.

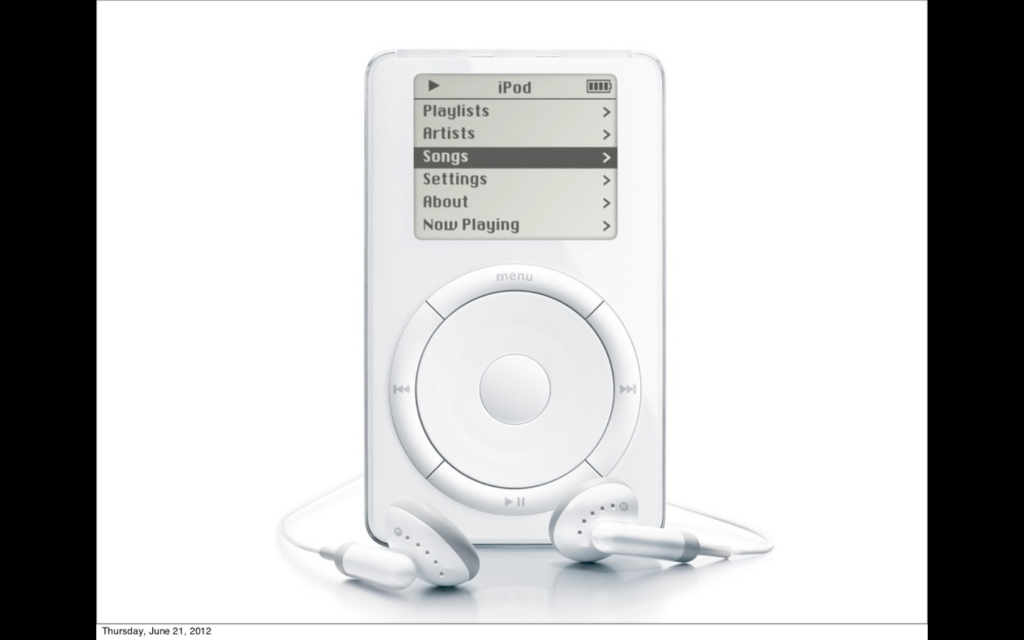

This is an example. Apple didn’t start their mobile revolution with the iPad or with the iPhone. They started with a music player. In content strategy at Brain Traffic, one of the things that we help clients do is figure out what the core idea is, their core content strategy, their core purpose. Really the core purpose of their online work, of their site, or their sites. What are they doing?

And in the beginning we usually hear something like “We want to serve world-class content.” Which is great. But everyone wants to serve world-class content. And the way that you can tell if this is narrow enough in scope that it can be executed with excellence is to imagine that internal audience, the makers. What happens if you take our pool of writers and editors and give them a statement like this and say, “Okay. Go do it.”

These phone calls don’t end well. So this is too broad, this is too generic. It’s not something that we can actually execute. So let’s say that our project is a site for houseplant lovers, people who are enthusiastic about their plants. What we’re going to do is try to serve world-class content for plant lovers. It’s closer, right? But that’s still a lot of territory. That could be almost anything about plants, and that’s a lot of words. So this is still too broad.

Now we’re getting somewhere. Let’s say that we want to publish uniquely helpful content (that’s content that can’t be found somewhere else) for first-time plant buyers, This anxious audience of people lined up to buy their first fern. This is going to be our strategy. So what do you think, writers, is this something that you maybe could work with? Oh, we’re getting closer.

So this is our core strategy, this is going to be the thing that we’re going to build on. That’s really quite limited in scope, certainly compared to “serve world class content.” This is narrow. This is small enough that we could actually work with it.

Where do we go from here? Well, we might say we’re going to tell our audience which plants won’t you kill immediately. And which ones might you like? Here’s some pictures of plants. We know you don’t know their names; here they are. And how do you care for them?

This is actually something you could give to a team of writers and editors and they could make it, especially if you then say: We’re going to do it by making a guide to 20 common houseplants. We’re going to have blog posts and videos. We’re going to post those every week. And we’re going to follow a specific publication process.

That’s something you can actually accomplish. So that is narrowing the scope until it’s small enough that you can do it really well.

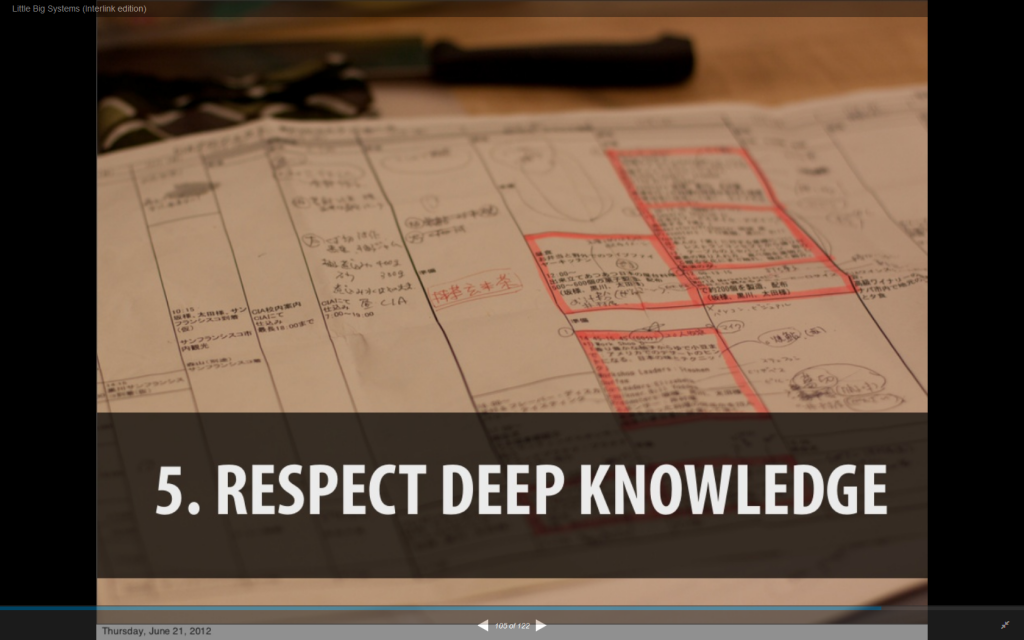

That brings us to our final principle, which is respect deep knowledge. This is a recipe diagram from a confectionery that makes wagashi. It’s partly printed, it’s partly handwritten. It’s been annotated and highlighted and passed along from chef to chef, and it contains quite a lot of deep information. One of the things that craft can teach us as makers is that we don’t need to reinvent everything from the beginning. In fact, we shouldn’t reinvent things if we can find deep wells of knowledge that show us how to accomplish them. This isn’t just the case of processes that we know. This is about finding those deeper pools of expertise, of mastery, that show us things we might not have thought about with our materials, with our artifacts, with our processes.

Back to Prada for a second. They have these climate-controlled vaults which are full of carts like this one. These are pattern books, some of them from the 1890s, and these are in common use at Prada. These get dragged out in 2012 as they are designing new cutting-edge lines. They bring out these old pattern books and documentation.

So this is one of the places that deep knowledge can come into our lives. Another is not just books but also the hands and the minds of the craftsmen themselves. These might be people on our own teams. They might be people in our client organizations. The CEO of Prada said something really interesting in an interview, which is that

I like to employ old people. I believe that a company needs a balance between young and old people. Young people are not necessarily the key to innovation.

Patrizio Bertelli, Prada CEO

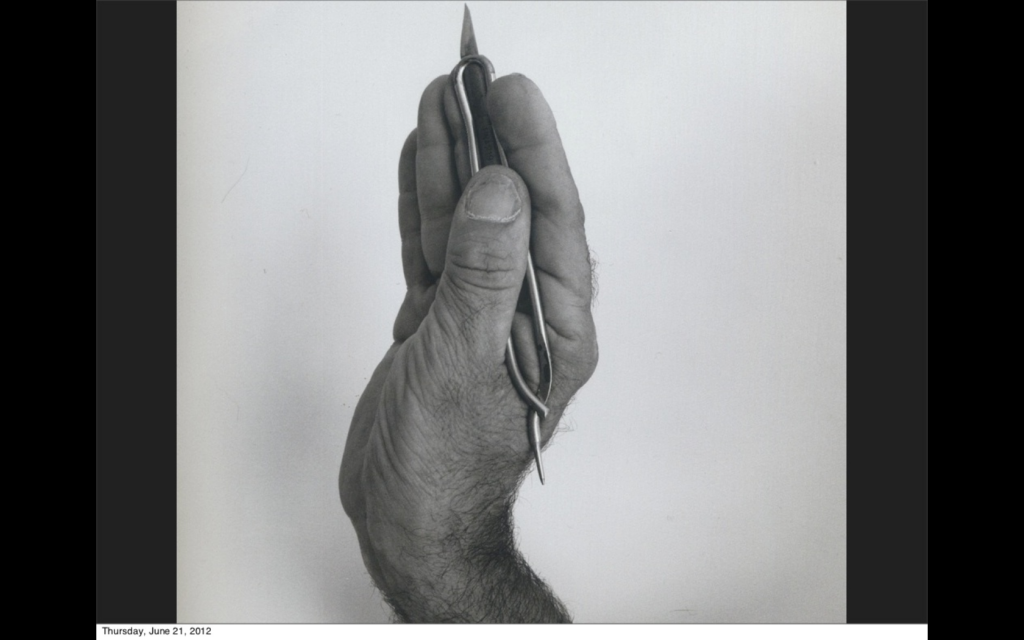

So when I go back and consider the knowledge implicit in a hand like this, some cases we actually are lucky enough to know specific individuals who can bring us along. We can take apprenticeships in sort of a traditional way. For many of us more likely it’s a question of looking back into the history of our own fields and saying, “Where are the masters in our work? What can we learn from?” So for people in my field, content strategy, it’s a new field but it’s really made up of a number of other fields.

If you go back and look, we’re taking from a very long publishing tradition of editors, managing editors, all the people who make books and magazines and newspapers. Also library science people. The librarians who’ve come up with cataloging systems and been slinging data via index cards in those amazing long drawers. Those are also masters from whom we can draw. Old-school information scientists have things to teach us. Museum curators have things to teach us.

Of course it’s not just in my field. I think another one that is particularly pertinent is web typography, which if you remember ten or twelve years ago, it was a pretty clumsy thing. We were all working with big Duplo, wooden-block children’s tools comparatively. And web typography has developed into a really sophisticated field with obvious connections back to centuries of type design. So it’s incumbent on us to do the apprenticeships, whether they’re literal or figurative, to find those masters and those deep wells of knowledge.

This is a guy who’s learning to make wagashi. He’s going to be at this for some time. Right now his job is to mix the color into the sugar until it’s even. He’s going to do that for a while. That may not be the most fun phase for some of us, but we need to do that kind of apprenticeship.

But we also need to take apprentices. When we do begin to develop expertise in our own field, whatever it is, we need to make sure that we’re bringing in people and teaching them what we know, through literal apprenticeships whether internships or by building bodies of knowledge. This is something that I think sets our industry apart. It’s an extraordinarily generous field, and I know that in content work in particular, the level of sharing versus the level of competitiveness is very very high on sharing.

There can be some dangers to a really highly-communicative online community. People can talk about an echo chamber. But I think there’s a lot to be said for not just the social aspect, but really communally building these deep pools of experience that are going to outlast us, that are going to help with whatever comes after content strategy, because I promise you this field will not be here in this form in ten years. It’s going to be something else. It’s going to be something also really exciting. But there are things that we can leave for the people who are going to be doing our work next. So, respecting deep knowledge.

All of this is an attempt to figure out how we can bring these values and practices of craft into complex system problems. But what would that look like if we succeeded? I think the answer is that we are working toward, or maybe we can work toward, a world of handmade systems. This is a workshop. These tools, many of them [are] made by hand modeled on James Krenov’s tools.

One of the books that Krenov is best known for is called With Wakened Hands. What I didn’t know until fairly recently— Krenov talks about working with wood, being able to communicate with the wood, in a really sort of non-woo way. He’s talking about what you learn from touching, what you learn from weight and density. These things that you can’t learn from reading. So he talks about the hands of the craftsman as being awake to possibility, awake to the wood, awake to what you might be able to make from these materials of your craft. It turns out, as I discovered just a couple of weeks ago, that the name of the book comes from a Lawrence poem in which Lawrence writes

Things men have made with wakened hands, and put soft life into

are awake through years with transferred touch, and go on glowing

DH Lawrence

I think this is something that we could be working toward. This is something, if we imagine a world of handmade systems, something that isn’t just a factory. Something where we don’t allow systems design, the complicated stuff, the thing that runs public transit and our really big, complicated systems, we don’t let those diverge from our craft, then we’re talking about a whole different kind of network of workshops. And I think that’s where it gets really interesting.

So I want to talk for just a moment about this one particular thing that Krenov made. I mentioned that he was famous for his furniture, which is quite beautiful. And for his books and for his teaching, which is he. But he’s also famous for this. This is a wood plane. Are any of you woodworkers? Do you know this? Have you used any of these? Not a big woodworking audience.

The thing about this, it’s the most literal interface between the arm and hand of the craftsman and the wood that he’s working on. It’s the thing that you actually use to smooth a plank of wood. It’s a pretty simple device. It’s really made out of a few pieces. It’s wood, it’s got a metal blade, and you’d think this would be perhaps and apprentice project, something that you learn to do early on. Krenov, as I mentioned he passed on in 2009, but for some years before that his eyesight became so bad that he was unable to continue work on his furniture. In fact his last cabinet had to be finished by his apprentices. He had to stop halfway through.

But even after his eyesight had failed, he continued to build, through touch, these wood planes and make them on his own time, at his pace, which was fairly quick, and send them out into the world at just about cost. So there are many many woodworkers of our generation who have in their possession one of these treasured Krenov planes. And like any other nerdy pursuit woodworking has its own sort of online rabbit holes and forums and you can find these people talking about the mystery of the Krenov plane and taking pictures of them. One guy that I was reading some of his stories about his plane, he said that he’d had it for 15 years and in those 15 years he had made 12 planes himself, going from quite crude as you’d imagine, to something that looked remarkably like a Krenov plane.

But there was a problem with each of them. Even the ones that looked like a Krenov plane didn’t quite feel right in his hand, didn’t quite have the same weight. And the closer he got, there was still something that eluded him and that sadly continues to elude him. I have hopes that maybe he’ll eventually make it.

The thing that sets apart the Krenov planes is the sound that they make. Most planes rattle, they vibrate in sort of an unpleasant way when you use them to shave the rough surface of the wood. But Krenov talks about this explicitly. It’s one of his sort of core ideas. He talks about the fact that when you have the right plane and you understand the wood and you slide the plane across the wood, the sound that comes across isn’t just an ugly vibration or a buzzing. You’re actually making music.

And if you hear the music, that means you’re doing it right. You have the right system, the right wood, the right touch, and you’re making the right thing. And I think that all of us, whether we’re doing little projects or doing big crunchy system design things, I think we could do worse.

Thank you.

Further Reference

Slides for Little Big Systems (though for a different, so slides are not identical).

An online community built around Alexander’s A Pattern Language.