Golan Levin: Our final presentation this evening is from Valencia James, a Barbadian freelance performer, maker, and researcher interested in the intersection between dance, theater, technology, and activism. She believes in the power of the arts to inspire change. In 2013, Valencia cofounded the AI_am project, which explores the application of machine learning and artificial intelligence in dance. The project has been presented at several international forums such as the 2015 International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Buenos Aires, and premiered their first evening-length work in Budapest and Gothenburg in 2017.

Valencia creates solo works which explore stereotypes and post-colonial narratives, and has performed internationally. She cofounded the Volumetric Performance Toolbox, a collaborative project with Glowbox and Sorob Louie, which envisions live online volumetric performance as a new way for artists to create and perform from their own living spaces, and audiences to communally experience artworks using minimal equipment. Valencia James.

Valencia James: Hello everyone. Let me just share my screen. Okay. Thank you so much Golan for having me on this amazing residency. It’s just such an honor and a privilege to be here with you all. And I just wanted to start this presentation by giving a bit of context about who I am and the lens that I bring to my work. So, I am a Black femme from the island of Barbados. This is a very tiny island in the Caribbean.

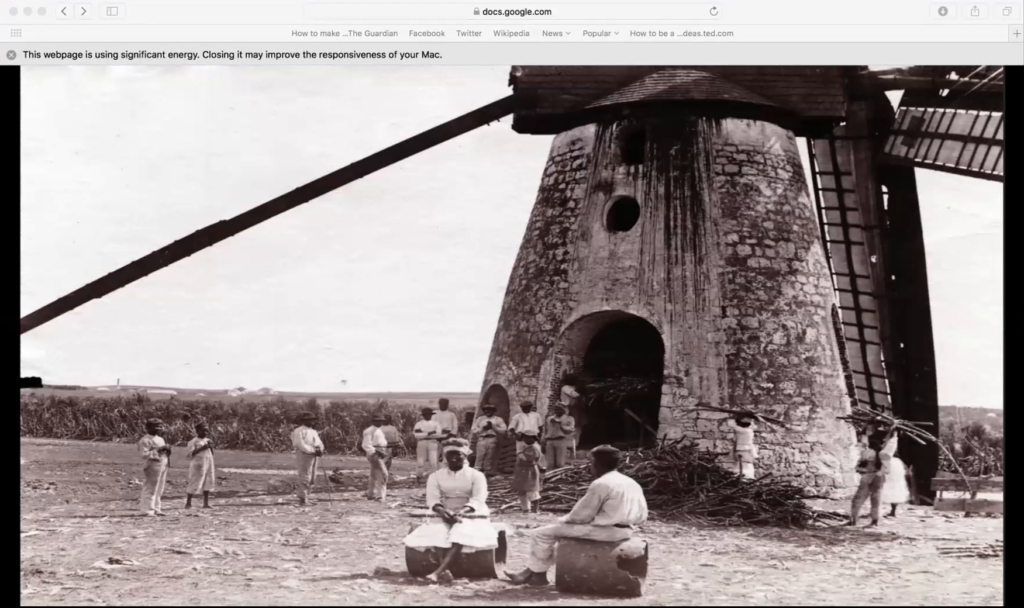

And it’s not just…like, it might be tiny but it has had a great significance in the way that we see the world working today. Because this was a key place historically in the British Empire and the establishment of the sugar trade and the transatlantic slave trade, because Barbados was known as a sugar island. And this was the first plantation-based society. And so this is where the first legislation was established that shapes the race relations in the US today, because it was first established in Barbados and then used in the United States in terms of how black people were treated and laws like…you know how a Black female slave, her children would be slaves as well automatically. And that’s something that was unprecedented at that moment.

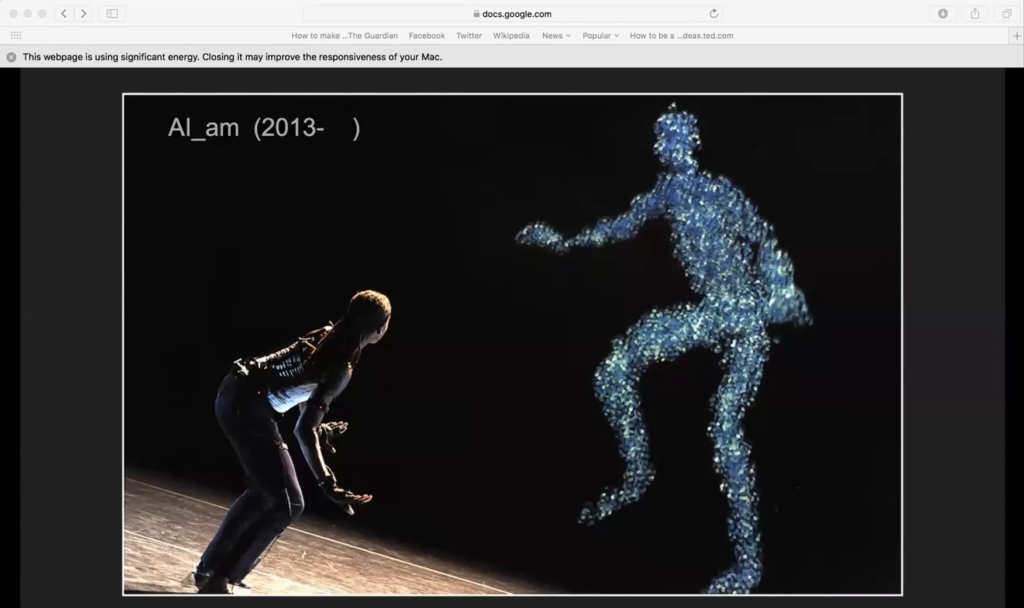

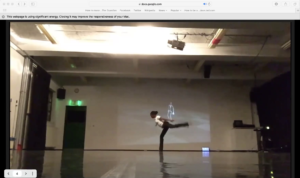

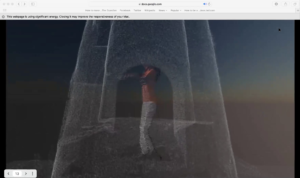

And so, it’s this kind of sensibility that I bring to my work, and also importantly I am a movement and performing artist. And so my work with tech starts from my movement practice. And it comes from a place of curiosity about how emerging tech will impact the way I create and how it will impact the future of performing arts. And so in this slide you see a still from the theater production “AI am here” that we premiered in 2017, which was a culmination of about five years of research with some creative technologists from Sweden and Hungary. And we established the project AI_am in 2013.

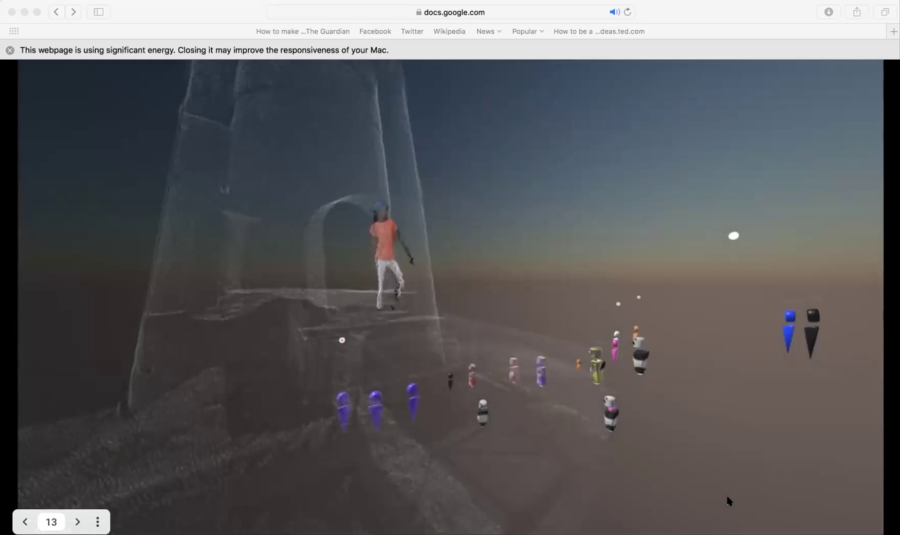

And so our initial question was how could I teach a computer to dance? And so, together with the creative technologists Alexander Berman, Gabor Papp, Gáspár Hajdu, and Botond Bognar, we developed a tool. And I’ll start that video. And so you can just see we created this open source software-based tool that I used as a dance partner. And I was thinking about how can we use AI as a way to inspire new movements. And so, taking the limitations of our researches—we didn’t have any access to a fancy motion capture lab—we created a tool that uses a very finite amount of dance data to create an exponential amount of novel movements. And this is like a low-rez version of the work that— We didn’t have money for really great renderings. But then we eventually got to a place that we could present the work and also speak to the issues of how machine learning was viewed in that time. It was a [indistinct] to me of like either it’s like an amazing savior or it’s a slave or something that we have to be afraid of. But we thought of how AI could be seen as equal creative partner.

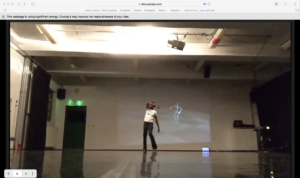

And I start with this because this was the starting point and the origin of the Volumetric Toolbox because as you can see in this clip, I am constantly looking at this flat surface of an avatar in a digital environment, and I got increasingly perplexed by this awkward divide of my physical space and the avatar’s digital space.

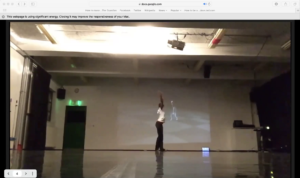

And then during the pandemic, theaters were closed and my performances were cancelled. And you know, we were looking at how can we restage this piece. And I realized well, what if I as the performer would go into the virtual space? And it was from this crazy idea that the Volumetric Performance Toolbox was born. And so this is a collaborative project between myself coming from an artist’s point of view and also someone who makes her own tools, and the spatial interaction lab Glowbox and Sorob Louie who is a creative technologist.

And we envision this toolbox as a way that artists can perform from their own living spaces using minimal equipment. And so it became possible via a fellowship by Eyebeam called Rapid Response. And so we were lucky enough to have funding for two phases. And it’s within the second phase that Golan reached out to me. And so like half of the time I was at OSSTA residency we were working on this project.

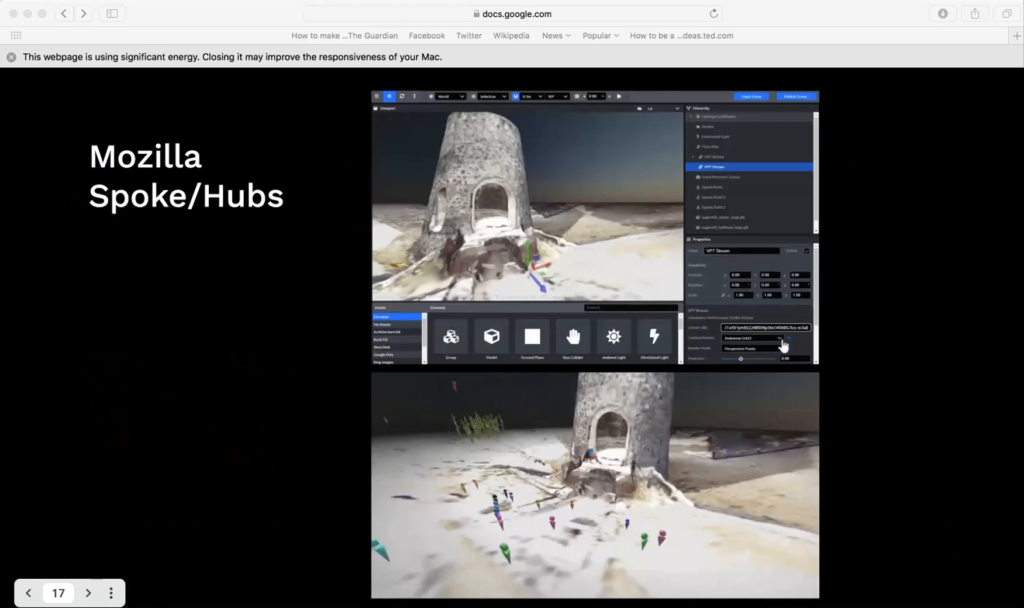

And so I’ll talk a little bit very briefly about the toolbox. We are envisioning low-cost open hardware, open source software, that would allow artists to create virtual performances in Mozilla Hubs, which is a social virtuality platform. And throughout this process that was very much spearheaded by my artistic creation of performance in Mozilla Hubs, we came up with an educational program that would allow any artist to create their own live volumetric performance.

And so our vision is that this type of technology would be accessible to the artist, which would be what we see as our primary audience. Performing artists anywhere, and especially those who do not know how to code and who are usually not part of the creation and use of technologies. As well as audiences that would be anyone who would like to have a communal art experience. And the idea is how can we make this happen using minimal equipment and not needing special equipment. So we found ways to have this all happen via web browser and using your desktop computer. And we’re very much committed to the tenets of liberation and with prioritizing communities that are usually harms by technologies.

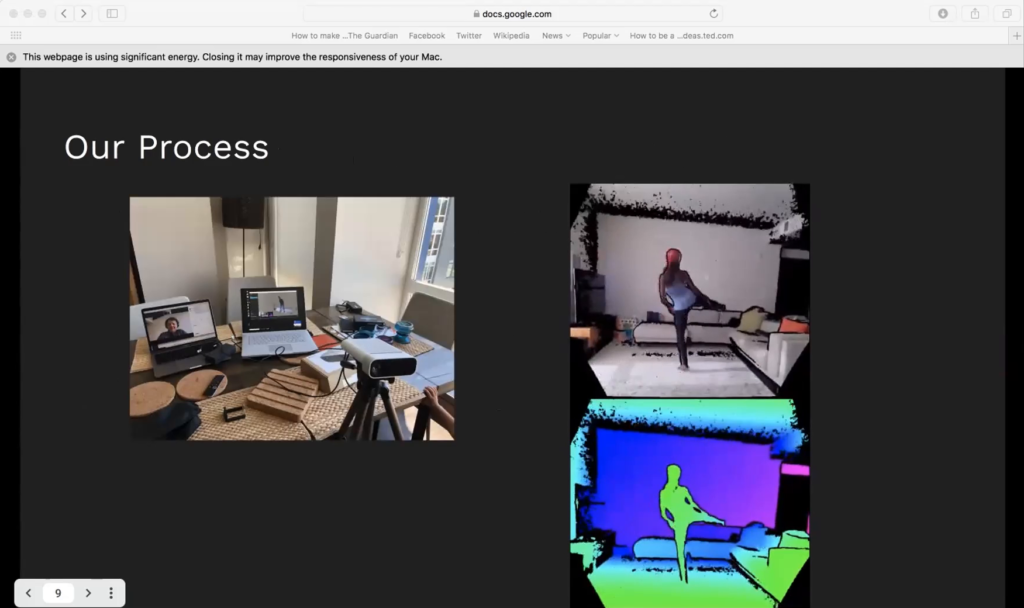

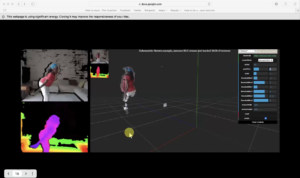

So, this project was very much spearheaded by just my curiosity with these technologies and the real need for performing artists to have a way to continue to practice their livelihoods and perform in the time of the pandemic when theaters were closed down. And so in this slide I’m just showing the start of that process. Because those artistic findings and my own process was what shaped the technical development rather than the other way around. And so my collaborator at Glowbox Thomas Wester—you see him in the photo on the left—shipped me a depth camera and we started using the Microsoft Azure Kinect camera to start my research. And on the right you see my movement exploration that I recorded. So the depth-sensing information is on the bottom and the normal RGB video is on the top.

And my interest as a performer in volumetric video was that first of all I didn’t need to use an avatar to represent myself in virtual space, because I could be represented as I am. And I think that’s very powerful being a Black femme approaching a virtual space that’s usually dominated by white cisgendered male users and creators. And so this was a big part of why volumetric video was what we used. And also that as a creator, I get agency to create my own stage. And that was really powerful in this time when you know, a lot of these online experiences and social media are already created for you and then of course influence the way you exist and behave in these platforms.

Afro-now-ism is taking the leap and the risks to imagine and define oneself beyond systemic oppression…The question is not only what injustices are you fighting against, but what do you in your heart of hearts want to create?

Towards an Equitable Ecosystem of Artificial Intelligence [slide]

And so early on in my process— This was like in July when you had the killing of George Floyd. And I was able to ground myself in my practice of connection with my ancestors. And I was very inspired by Stephanie Dinkins. She’s a transmedia artist and her quote on Afro-now-ism and looking at what in my heart of hearts I want to create, even in this time of unrest and wanting to be reactionary, but how can I really speak to the issues that matter to me but from a place of true creation and ancestral connection.

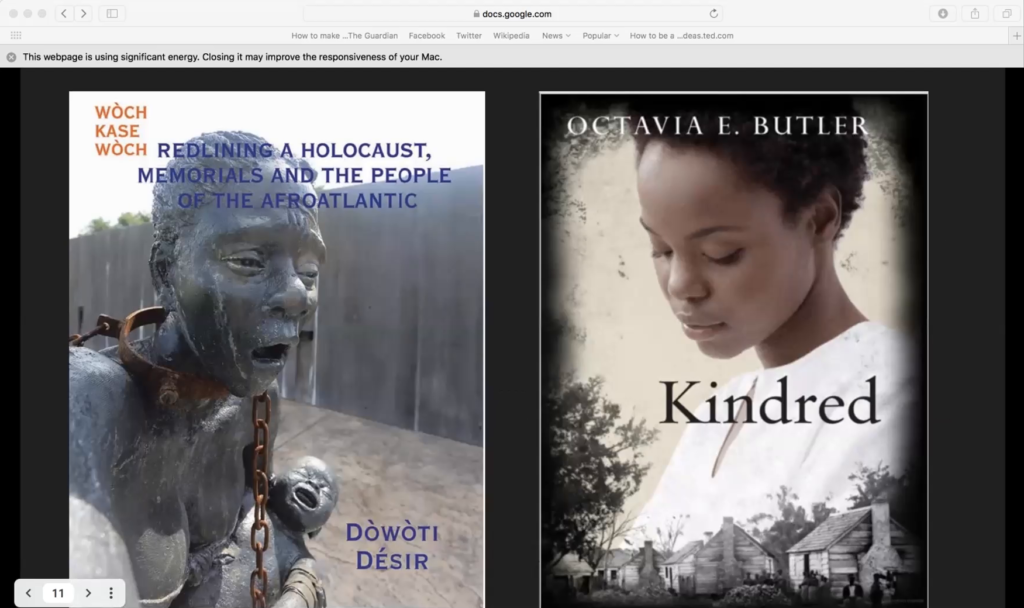

And so I was also very inspired by Her Majesty Queen Mother Dòwòti Désir’s work; she’s the queen mother of Benin and also a scholar and Voudou priest. And she speaks about the concept of spatial justice as the right to the African descendants to the memory and commemoration of the injustices that they had been subjected to. And also Octavia Butler’s work Kindred.

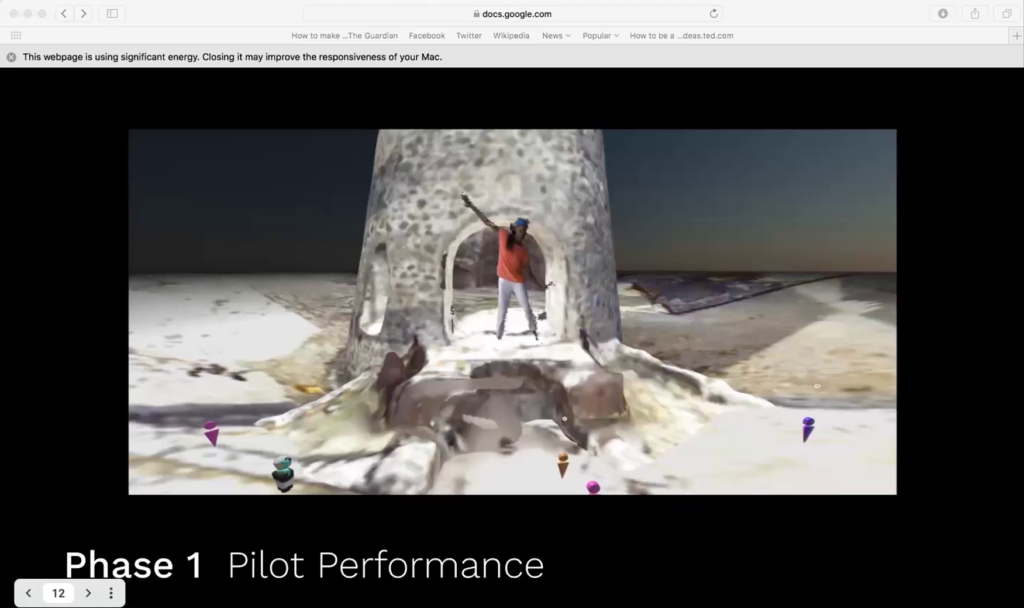

And so all these influences brought me to the creation of our first volumetric performance. And you probably recognize maybe the structure from my earlier slide, because in my research I also found SCI-Arc’s spatial data of a sugar mill. It’s a sugar mill ruin, and this was actually scanned in the Caribbean. And this is a very important kind of structure because you see these ruins in all of the islands around the Caribbean. And so with this work, I’m thinking of digital spaces and virtual environments as a possible site for healing and reclamation of spaces that were historically filled with pain and injustice. And so I’m gonna just show a short clip.

- [stills from ~14:19–15:05 of recording]

So, what you just saw was one of our early performances. And we tested out the concept there, and one of the big questions we had was about liveness.

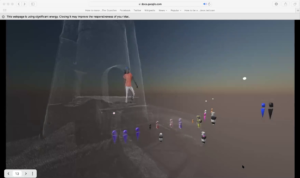

And so in this photo and in the clip you might’ve noticed some little avatars floating around. That’s actually the audience members within Mozilla Hubs. And again, that’s a social virtual reality space. You can access it through your web browser by a URL, and you go in there and you’re embodied by this avatar and you move around using the WASD keys. Kinda like you’ll be in a video game. Personally it took awhile for me to get used to moving in that space. But what we found was that we got beautiful feedback that you really had the sense of liveness. And this was a big question about how do you replicate that communal experience and that sense of liveness that we have when we experience a theater piece together.

And so with this pilot performance, we were able to see that actually yes, you do have that sense of liveness and the sense of witnessing and the sense of intimacy in that space. And so in this clip you’re seeing a still from the Q&A session, where we could use our webcams like how we do with Zoom, and we could have that kind of interaction even in this kind of virtual space.

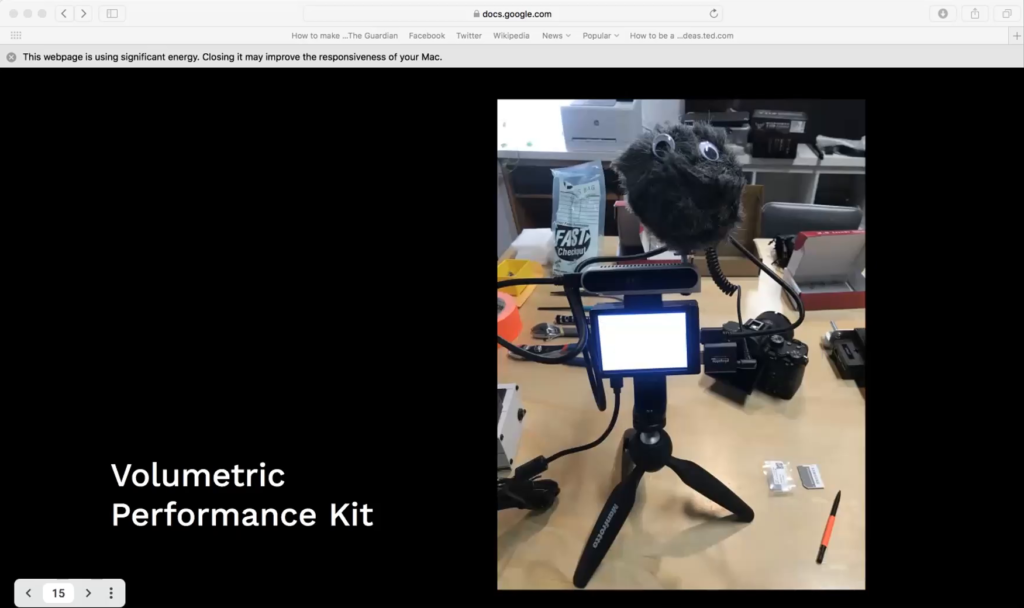

So from this there’s a big question of okay, how do we package this in a way that any artist can create their own volumetric performances in online spaces and not need a huge budget. And one of the things that came out of this first phase was the performance kit, which is the low-cost open hardware that was developed by Sorob Louie and also Glowbox. And so this kit has a small Intel depth camera and a Raspberry Pi. And so the whole idea is how will we make this— Because normally this type of equipment, it needs a very expensive setup. And so this costs about $400, and so this is something that we were able to ship to artist to get them set up quickly.

And the next element of the toolbox is the open source-based customized software that Thomas Wester from Glowbox developed. And this is where we can tie the pipeline of the Mozilla Hubs platform together with the depth video that you get from the hardware and create a 3D representation of the artist in virtual space.

And so by tying these strings together, we were able to create the performance. This is showing how we placed the volumetric stream. The stream also goes through a livestreaming platform called Mux. And in that way this is how we create the performance.

And what we did in the second phase of our fellowship at Eyebeam was to bring this all together into a series of workshops and create a residency within a residency. And so the goal of these workshops was how do we build a community of creators to have a platform of colearning and cocreation. Because you know, as the performing artist I was still grappling with how do I even start creating in 3D? I don’t have coding skills. And I was thinking about how can we make this easy for anyone just like me to pick it up and start creating?

And so we hosted this kind of pilot residency in December and January, and we created this in collaboration with Simon Boas of Glowbox as well as the wider community of creators like Lauren Lee McCarthy, and LaJuné McMillian, and Tony Patrick. They all—as well as [indistinct] and Jesse Escobedo and [indistinct], and they all came together via Zoom. So this is a still from our first call. And we came together to speak about how can we create a future for online performances and envision a decolonized and decentralized future and vision for it for the performance? Because I really think of this way of creating as like the birth of a new genre that will continue to be relevant and groundbreaking beyond the pandemic. I really think that once we can get back into theaters that new shows would also have a virtual element to it.

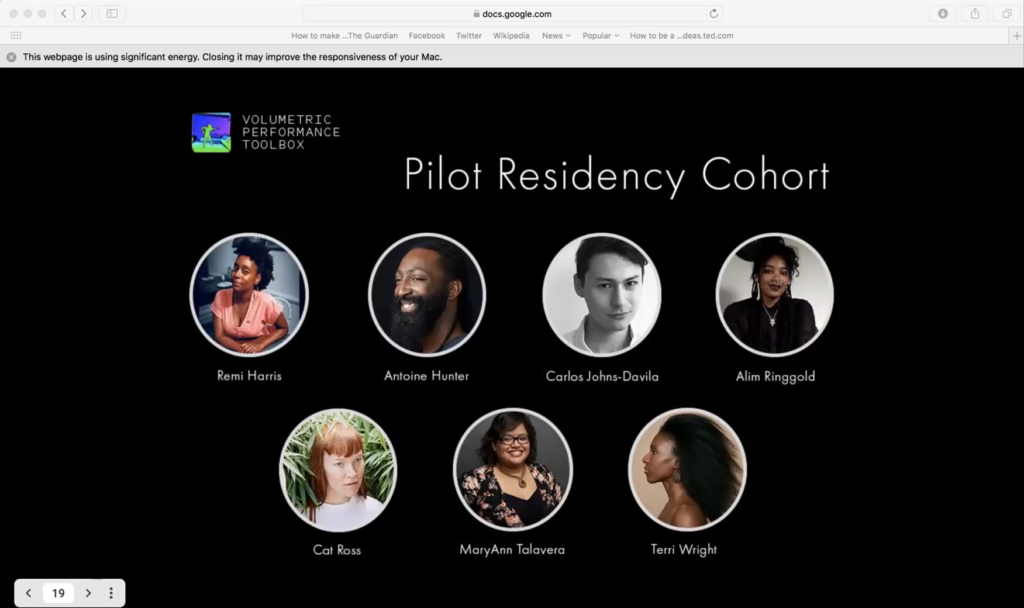

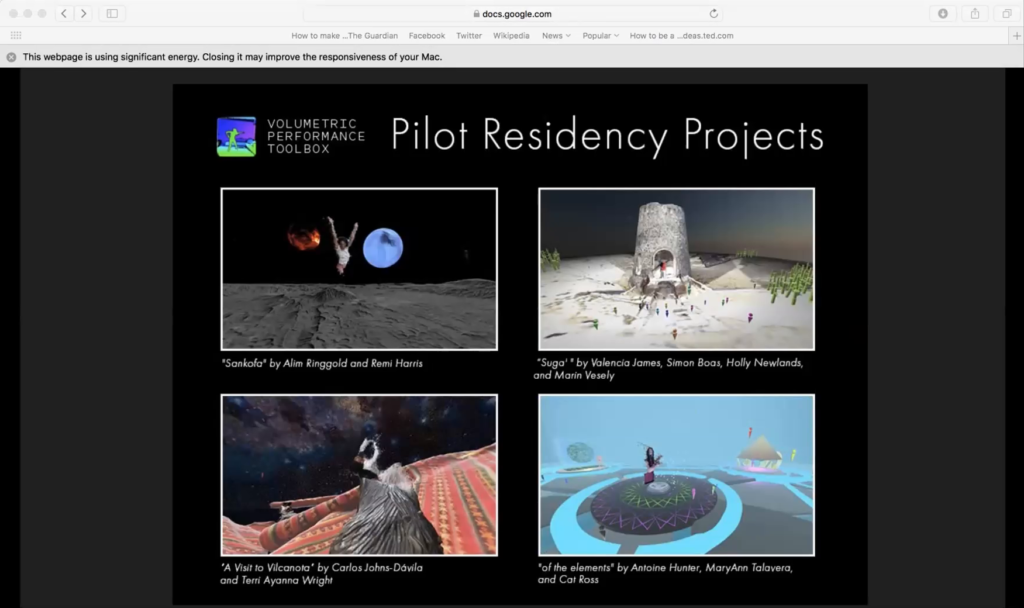

And so we were thinking about how can we create this in a way that makes sure we include communities from those marginalized communities that tend to be left out of the creation of these tools. And so we invited seven multidisciplinary artists from these different communities, including disabled communities, LGBTQ community, and Black and indigenous and people of color. And we shipped each of these artists a kit, and had these workshops of cocreation. We also made these workshops open access via our Medium page.

So this was the result of that process. and this is like a vision of how we see the toolbox used going from now on into the future as a way in which artists can create their own worlds based on the core values that we have set about through this residency. It was really important that we set out shared community values that are based on the tenets of liberation for all. And so we think of this as a way that we can empower artists of any kind to build their own worlds and really speak to real-world issues from their actions in virtual space. And I really think that this is the huge potential of this work.

And so I’m out of time I realize. And so I’m just gonna skip to our next steps…

Throughout this residency I’m very grateful for this. Thank you again, Golan. And to my fellow cohort and everyone at the STUDIO, in this residence we were able to make the next steps in onboarding more artists onto our custom Mozilla Hubs client so that they can continue using the platform for their own experiments and creating their own performances. And we’re also learning. I’m personally learning a lot about open source projects and how you can sustainably create this. Because I’m really invested in making this about a community of contributors and creators, and making sure that it’s something that anyone can approach and create and contribute to.

So thank you so much. and if you would like to join us on this journey, please don’t hesitate to contact us at volumetricperformance@gmail.com.

Golan Levin: Valencia, thank you so much. I was amazingly privileged to have the opportunity to attend the performance in Mozilla Hubs. And it was really extraordinary to see somebody performing live with a point cloud projected into the browser and immersed in an artist-designed three-dimensional virtual environment that I could freely navigate within. It was really… I haven’t seen something like it before. And I hope we see more of these both from you and from the collaborators you have.

I thought something that we could do that would be fun is actually have like a five- to ten- minute kind of conversation with A.M. and Bomani, who are still here with us and invite them back. A.M. and Bomani, if you want to jump in.

I can kick it off with a question but I would love to actually just also hear the three of you ask each other questions as well. Hi, Bomani. And welcome back A.M. if you can join us as well.

A.M. Darke: I will, but I’m finishing my last bite of lunch. [all laugh]

Levin: That’s super. I’m gonna maybe spiel for just a second. Because I mean, it’s been a huge privilege to work with you this past semester as our creatives in residence at the STUDIO and as part of the OSSTA platform.

I think that in developing open source software toolkits for the arts, there’s a sort of…already a double struggle. The double financial struggle, right, of working in the cultural and arts sector. And then also working in the open source sector. Because you know, there’s not like VC money that’s kind of pouring in to fund this work. So there’s a double struggle there. But you’ve taken on the triple struggle of not just making some tools that happen to be free and also help us make pretty pictures, but also that such an important aspect to what you’re doing in terms of decolonizing technologies and creating feminist and anti-racist technologies as tools to empower others. I think it’s a huge challenge, given histories of representation in animation and the arts. Given histories of bias and violence in machine learning and artificial intelligence. So there’s a third struggle there. And there are so many different strategies that I see in the work that you’ve been doing. Increasing representation among the contributors. Increasing representation among the users and audience. Increasing representation in the artworks itself that are made with these systems. Increasing access. Being careful about textual languages of framing, design languages, codes of conduct. I wonder if maybe you could speak to your favorites of these. You know, how hopeful you are for these kinds of things. And also if you have questions for each other that arise from your own presentations and your own experience over the past few months.

Darke: I don’t have a question, I have just really a comment. I’m so inspired by both Bomani and Valencia’s work. And I find it really heartening that all of us are really having an eye toward accessibility, right. Like cultural, technological accessibility, community accessibility. And something that I feel wasn’t available to me as I was moving through these various systems, whether it’s visual art, technology, the intersection of both, like even academia, is that awareness of a kind of culture accessibility. Being thoughtful about the practices, being thoughtful about the community. You know, thinking about the kind of implicit hierarchies around who’s proficient or who has certain kinds of knowledge. And I really just…you know, I see that deep community focus that’s not just sort of…it goes beyond just the language. It goes beyond just saying like oh, we’re going to create a space and here’s a community,” but like understanding— I forget what that amazing quote that Bomani had up, which was like— Oh Bomani, you have to jump in and actually just say it. That it’s like a continuous practice, it’s not sort of like a momentary thing. And I just…I’m both overwhelmed by that as someone who’s now starting in caretaking an open source project, but also feeling that responsibility and that privilege to sort of hold the space and try to nourish it. So yeah, that’s my long-winded comment.

Valencia James:Yeah, I’m also very inspired by you all. And A.M., know that your work was cited in those early workshops by some of the participants as one of the inspiring projects and people out there doing this type of work of community and decolonizing. And I’m very much inspired as well by the p5.js and ml5.js community in understanding how…the code of conduct and community statements, that was early on in our process as well. That was a big inspiration. And so I’m still learning about how we can build community and make sure that we’re not working in silos. Because that’s something I had to unlearn. So yeah, I’m just inspired to learn more about those practices. So Bomani if you could speak a bit about the ways in which we can learn to create more collaboratively in that way that would be great.

Bomani Oseni McClendon: Yeah, I want to echo you all in saying I’m super inspired by the things that you all shared. And I’m always appreciative having the opportunity to just be in the Zoom, or in the space and be able to hear and kinda understand the way that you all come to your ideas. And I agree, I think that one of the things that I’ve also found personally has been super important in this whole durational practice of open source is just like, finding ways to kind of stay energetic and revitalize ourselves. I think meetings like this are important, and I think having conversations and getting excited and generating ideas is important.

But I’m also really excited by the way that both of you all in the presentations that you shared have put in a lot of effort to create these forms of community infrastructure through programs, or workshops, or by hiring and supporting folks, sending out open calls. And I’m actually really trying to understand how to do that better myself. And so I would love to know if either of you would be willing to kinda share just some of your insights for people who maybe are just getting started with that process of trying to…for lack of a better word socialize or “communalize”—I don’t even know if that’s a real word—parts of their work in the open source kinda domain.

Levin: Both Valencia and A.M. made residencies within residencies.

Darke: [laughs] Yeah. I mean, I can tell y’all how I’ve been stumbling through it, right? I’m like, I think the first day of in this residency I was like, I don’t know how to do a residency. I guess I’ll learn. Maybe I’ll be one week ahead of my own.

You know, I’m someone who that has historically been very siloed, has not had many collaborations, have— You know, I love to collaborate but I found that as I was coming up my ideas were not understood until they were complete. And then people are like “oh, that’s so smart” or “that’s so brilliant,” or “I just couldn’t imagine it before.”

And it’s like, you couldn’t imagine it because it was centered on like, this body or in this experience. I always kind of felt a little like, resentful because I didn’t have all of these skills. I wasn’t a programmer. I didn’t— You know, I had to very slowly start picking up all of these skills. Because I didn’t have the option to really work with you know, a wide spread of people.

And so now, like— Hell, I’ve been doing this for like ten years I guess now, it’s like oh okay. I have a little bit of a platform. I have this opportunity. Now people are listening to the things I say, which is still very…weird. And I think I’m having to go through this transition of like, oh I can collaborate. Oh I don’t have to do everything myself. Oh, I can ask for help. I can have a vision and it’s okay to say like, “Can you help me with this?” and not just can you like employ or deploy my vision but can we work on it together? Can we build and expand?

And at least for me this has been a part of my practice for…for a while, is just starting with a kind of radical vulnerability and transparency. So actually, we didn’t have enough time but I actually started my talk with— I started to make slides, and I made one slide. And I was like I hate making slides. Like I literally hate it. I find it very confining, and rigid, and it’s not my style. And I went on this whole thing like why am I doing this? Why am I constantly feeling like I have to perform in a certain normative way? And it’s like… By the way, if you could see my slides all my slides have literally the speech in them and I was like yeah, that’s the way to do it. To be honest about the fact that like, I don’t have a lot of models to tell people this is what I want to do and be transparent about the fact that I’m not totally sure where it’s going.

In my initial call to the residency, I had like— You know these three things that you have to agree to accept the fellowship. And the third one was like, to be patient with me as I figure out how to navigate this thing for the very first time. And you know, it’s really scary but I found that kind of like— Literally going on Twitter and being like “This is what I want to do. I’m looking to craft loving depictions of blackness. Where do I start?” Yeah, I felt very embraced and welcome, and where I used to feel like an island I feel much more like an archipelago, you know, connecting with folks. So that’s where I start. With just…the thing that we don’t see. Especially in software and even certain art spaces, it’s like everything has to be—even with a presentation—everything has to be fully-formed and polished. As if not sullied by the grubby hands of the creator.

And it’s like no, I’m grubby. I’m a mess. But I’m an excited mess. And like, if you want to get in this mess with me, let’s do it. So that’s how I’m doin’ it.

James: I love that. Owning like, this is a process, and it’s gonna be messy, and we’re figuring out as we go, right? I must say that sometimes I can get overwhelmed. Because at the beginning of the second phase, when we were trying to figure out how to make this residency. So I can relate to what you’re talking about. It was kinda like, the best advice I got was just to keep having conversations with people who were interested in the work. And it’s through those conversations that I found okay, maybe the way I was thinking about it before is limiting so why not make this in community?

And at first I was like, oh how can we make this for movement artists? And I was thinking like, [indistinct] artists, we’d do this. But I realized that no, we need to have people from movement and media…you know, so everyone can make support each other. And then I realized that oh, it could also be a time of colearning. So get people skill sharing from my community. Just coming in and sharing, from people making 3D models to…I don’t know, world-building—we had Tony Patrick give us a world-building workshop which was amazing. So, I realized we have to do this in community.

McClendon: Yeah, I love that. And I love…A.M. in response to kinda what you were speaking about with the slides concept as well, I think that’s something— That brought radical vulnerability, something I’ve also been trying to learn. Slowly, but trying. And it actually came up in a conversation with a new contributor the other day, where someone was kind of like “Hey, I’m noticing these bugs. And I’m noticing these issues in some of the documentation” and so on and so forth. And I’ve recognized that at that moment I had to just kinda be honest like, yeah…there are issues. Y’all are fittin’ to get some bugs, some documentation errors. Y’all fittin’ to get some broken examples. Like that’s just where we are and I think that being able to like, instead of… Personally I think one of the things I need to remind myself of is that the way to address that is not always to just rush and try to make the fix, and instead it’s just to be okay with something not being “finished” or being “polished” but rather just being okay with the fact that like, we’re in just different stages of brokenness or you know, maintenance, or recovery, so and so forth. So yeah, I think that’s something that I really want to reflect on as well from what you all are speaking to.

Levin:

I think I’ll wrap it there. I want to thank all three of you so much. For the audience online, you can follow A.M.’s work the Open Source Afro Hair Library. Valencia James, the Volumetric Performance Toolbox. Bomani has been working on the ml5.js toolkit for machine learning on the Web. I want to thank all three of you so much for your wonderful contributions to this evening of presentations, and more generally to our Open Source Software Toolkits for the Arts residency at the STUDIO for Creative Inquiry.