Charles Godfray: A nation that cannot feed itself has no legitimacy and will fail. Ever since humans organized themselves in societies and city-states and nations, it’s been at the forefront of rulers’, politicians’, minds, how to feed a nation.

Now, I’m a population biologist, and the founder of my field and incidentally one of the founders of economics was Robert Malthus, who 200 years ago wrote that human population will inexorably increase beyond the capacity to feed itself. Human population increases geometrically, food supply increases arithmetically.

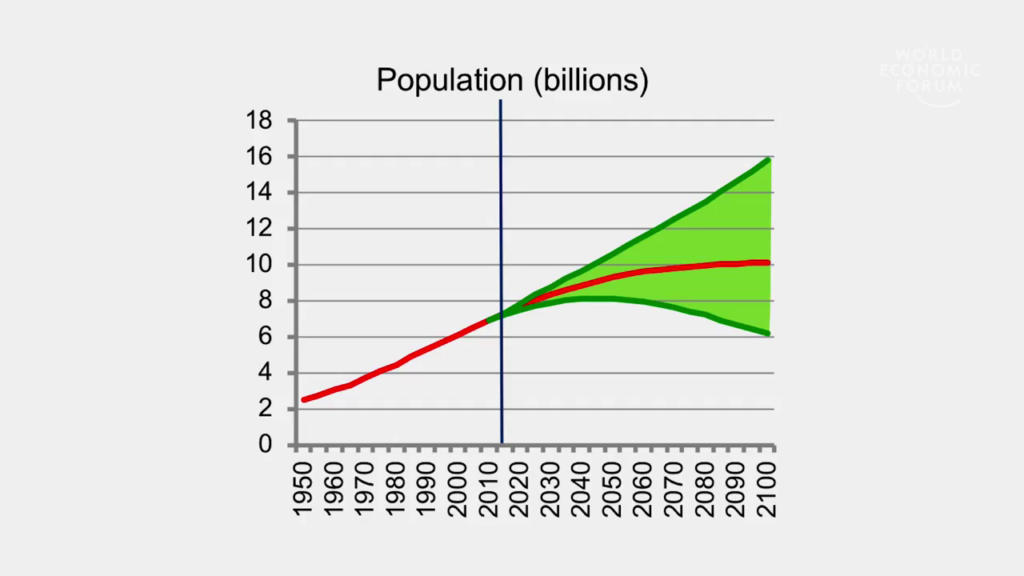

Now, the most extraordinary thing that’s happened in my adult intellectual lifespan is a demographic transition. The fact that human population fertility will reduce itself naturally in a non-coercive way if we get things right. Intellectually, we can now argue against Malthus, which when I was a student we couldn’t.

Demographic transition, you have to bring people out of poverty. You have to provide access to reproductive healthcare, and education for kids—especially for girls. Get these right, get these sensible developments right, and population growth rates go down.

And global populations will probably plateau at around 11 billion—which is still a huge challenge to feed but to me it’s game on. But we have to do things across the whole food system. Across waste, across consumption, across governance. And what I’m going to talk about, which is about producing more food.

Now, in the past when we needed to produce more food, we found a new continent. We cut down forests. We have neither of those options today. There are no new continents. And as Nick Stern said, probably the most efficient way to get carbon dioxide into the atmosphere is to cut down tropical rainforests. So we have to produce more food from the same agricultural footprint. And I call that “sustainable intensification.” Many other people call that sustainable intensification. And this has been the focus of a lot of reports recently. I want to put a little flesh on the notion of sustainable intensification; what one can do to produce more from the same footprint with less effects on the environment.

Look at these two wheat fields 300 years apart. We have bred wheat to be much shorter and more productive. There are a myriad of things we can do with modern technology and plant breeding not only to increase productivity but to increase resilience.

And it’s not just in the rich world. This is orange-fleshed sweet potato produced by conventional breeding, which is doing wonderful things addressing vitamin A and other nutrient deficiencies in Africa. Much we can do, and it’s exciting we can work not only on the rice, wheat, and maize that’re traditional crops, but in the so-called orphan crops.

One can use technology, precision agriculture. There is much we can do taking information from satellites to get the resources, the agrochemicals, the nutrients, exactly where you need them. So again, you’re increasing yields, with less input.

And it’s not just in the rich world, this is microdosing. Giving farmers in developing countries the knowledge to put exactly the right amount of fertilizer—that’s a Coke bottle top, just at the base of a maize plant—and providing the financing so that the farmer can actually go out and buy the fertilizer.

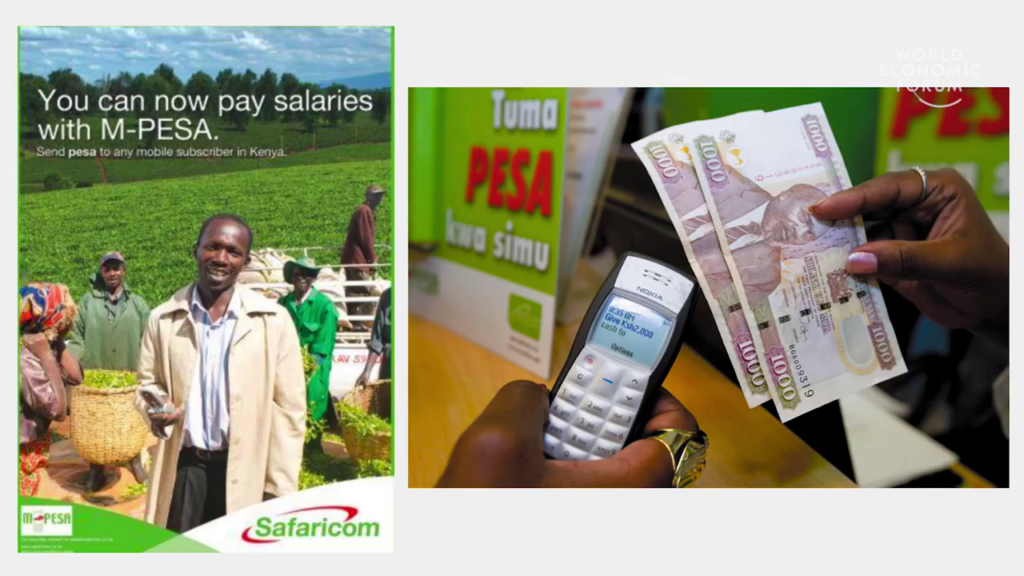

Massive amounts we can do with data. This is another example from East Africa. Where I work in East Africa I get a better signal than where I live South of Oxford on my mobile phone. Huge amount of information coming through apps. Farmers now have access to the type of finance we take for granted in the West.

Now people worry about sustainable intensification—it’s the way of bringing in GM or bad animal welfare through the back door. Sustainable intensification is a goal, it’s not a trajectory. We as a society can determine what we can use. For me, I’m completely happy with GM if done responsibly. I worry about animal welfare.

There’s lots of challenges ahead, especially around climate change. But I genuinely say to my students that I am more optimistic about the future and feeding the world, at my age, than I was at their age, again because of the demographic transition. It really is game on, there’s a lot we can do.

And I leave you with— I’ve talked about exciting ideas looking ahead. But what are the next ideas? Is it artificial meat? Is it alternative proteins? Is it some of the ideas about growing crops in urban agriculture, these megalopolises? It’s a really exciting time. What are the new ideas that we’ll see in the next ten years, twenty years?