Denise Caruso: What I want to talk about is something that has plagued me and concerned me for a long time now, which I guess one technical term for it is “gradualism,” how much worse things have gotten very slowly. And I think it’s really true in the privacy/security area. It’s true in a lot of places that have to do with technology because normal people are a little intimidated by it and they don’t know enough to know what they should be watching out for. So I found this—I know, before anybody corrects me that the frog in the water thing has been disproved. Nobody has ever done that, it’s not a real thing. But, it’s a great analogy, so I’m using it anyhow.

Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985)

So this talk is nominally about gradualism. (We’ll see.) One of the things that came to mind when I was starting to put this together was a book that was very important to me back in the late 80s, early 90s when I started working in the digital media space. How many of you have read this book? [looks around room] Excellent. This is Neil Postman’s meditation on the comparison between Orwell and Huxley, and his conclusion, or what he proposes, is that Huxley was right. So I was poking around online. One of the things I was trying to do in this sort of gradualism vein was to see how bad was it, and how bad has it gotten, and what have people come to believe about this. So I found this amazing 1987 BBC series called Secret Society, and you should watch it, it’s like—for one thing the clothes are hilarious. But it’s kind of remarkable.

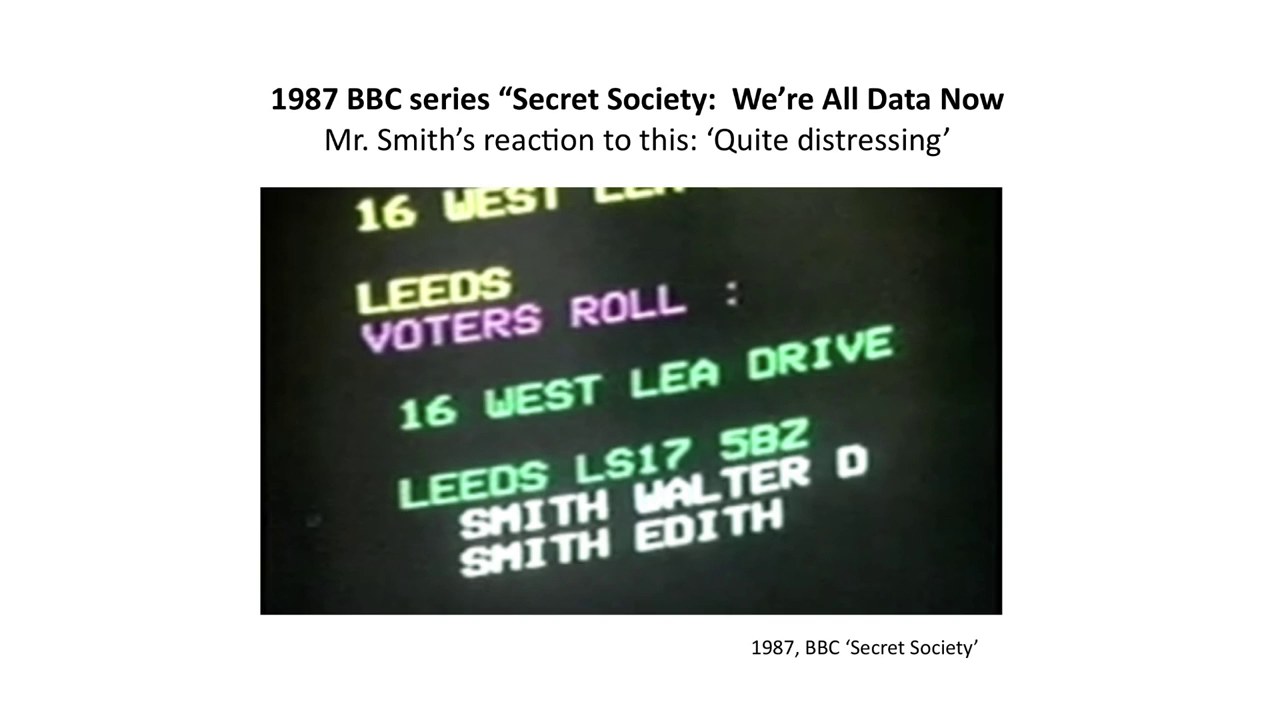

This reporter was doing this expose, the episode was called “We’re all Data Now.” Little did they know. There was a computer, with a CRT that was like five miles long, deep. And they were looking up people’s names off the street. “We want to show you, we want to see what’s available to the public about you.” So they brought people in and I really wish I could show you the video ‘cuz it was amazing, but for some reason this one amused me more than anything. These data came from voter rolls, so this is I guess where it started in the UK, was these councils—we’d call them boroughs or cities or whatever—would sell their voter rolls to whoever wanted them. And didn’t tell anybody about it, but they just did it.

So he looks up this guy, Walter Smith. This was the sum total of what was online about Walter Smith, and his wife Edith. You should’ve seen the guy’s face, he’s like, “Oh, this is quite distressing.” And people were very adamant about how they felt about it, so “What do you think of government selling the voter rolls?” Huge majority against it. “Do you approve of this information being sold to national data banks?” Even more: no, no no no.

Big Brother is the least of your problems, Inside Silicon Valley, Sept. 3, 1989

This was a column that I wrote in 1989 in San Francisco about this new breed of entrepreneur who’s getting access to all of this information and selling it whether you like it or not. And I actually cut out the quote in there; it was a consultant who was on Compuserve. Which half of you probably don’t even know what that is, but it was a very old old old online service, so I thought “wow, okay.”

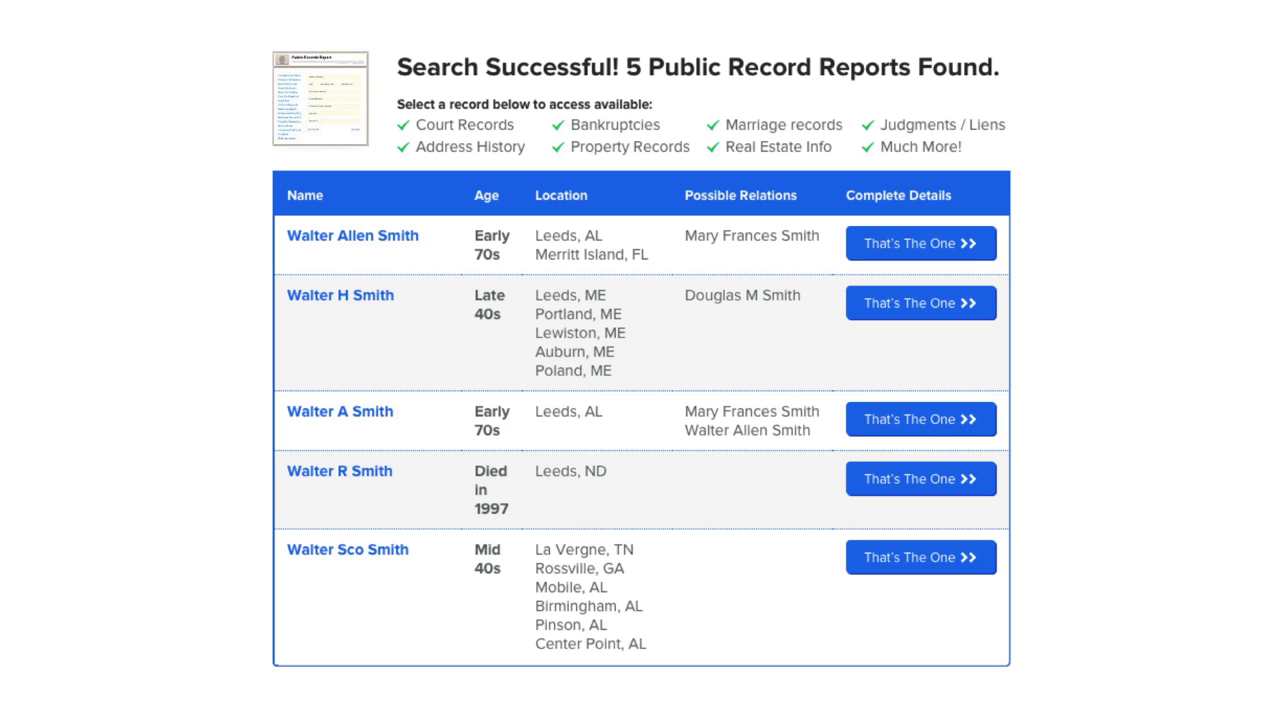

So then I just thought “Well okay, I’m going to look up Walter Smith” now. And he would have a heart attack if he saw all this stuff now. I think this is PeopleSearch or something like that. It just piles up all this stuff. Credit card, court records, addresses, property records, criminal records. Some of them even give social security numbers, as you know. So it’s really a big change just for less than thirty years. That’s a lot of data.

I didn’t include this because there’s already too much text on these slides but the Pew Internet people did a report on privacy and the numbers were actually lower than in the Gallup poll that the BBC took for things. Everybody’s information is sold now. Nobody even thinks about that being a problem, but the percentages are even less, like 61% or something of people said, “You know, there should be a law against someone falsifying your records” or something like that. It’s you know, frog in the pot.

I thought it would be fun to look at some of the comparisons between Orwell and Huxley based on some of the stuff that I have found around. So Orwell thought we were going to be deprived of information, and Huxley feared that we’d have so much that we would just be floundering around in our own juices not able to do anything about it. This is a headline from last December [2013] that I called everything that’s wrong with the world on one screen. What do you do when you read something like that, it’s like “oh my God I’m going to go back to bed.” Orwell thought that the truth would be concealed. Huxley said no, it’s just going to get drowned. This is a Google News Page:

Weather, sports scores!, Comets did not bring water to Earth, Home Depot. It’s just too much. And Orwell also said we would be captive, but Huxley said we would become a trivial culture pre-occupied with some equivalent of the feelies:

I mean who cares?

The other thing that Huxley said was that people would come to love their oppression, and the technologies that would undo their capacities to think. I pulled this off of iTunes’ App Store today. “Positions for the last four hours” for pretty much anyone whose phone number you have, which is followed by this really creepy but true situation. And it just seems like people don’t really put those things together.

And then in terms of undoing our capacities to think… This may be a little bit controversial here but I feel like Google has, although I use it four billion times a day, it’s really kind of flattened information. One of the courses that I teach has to do with research methods, and if it’s not on Google Scholar nobody looks anywhere else. I couldn’t find a number to show how many journals are not online versus how many are, but there’s a ton of information that will never make it to Google because it’ll just be too hard to get it there. But it’s stuff that’s part of our scientific and cultural record.

The other thing that’s interesting to me about this was back in the day when I used to be on this TV show called “The Site” (That should date it for you right there.) MSNBC did this show about the Internet and a guy that I knew for years and years, he had been part of the programming, technology, cypherpunk, everything kind of community in San Francisco for ever said, “This is evil. People don’t have any idea what goes on underneath that. How are they going to figure out how to find stuff if they don’t know what’s involved in doing that kind of a search?” And I thought, “Oh for God’s sake.” But it’s the same kind of complaint that people who are very very nerdy in the computer sense can be very prejudiced against Macintosh, because it hides the complexity. And I feel that. I don’t know that I would advocate having to teach everybody how to program, but I will say this: Being in this room for this week with all of these amazing women who know how to program, it’s kind of a life-changing thing. It would be a good thing for people to know how to program.

So undoing our capacity to think. This is another one that I think is really interesting. This all might be evolution stuff, I don’t know. Maybe we’re evolving out of our ability to hunt and find, and what we’re doing instead is figuring out how to look for things on the horizon, but this is interesting, that comprehension is different when you read on paper; better than when read on screen. And the other recent story that was interesting to me along those lines was that when you write notes by hand, you remember them more than if you take notes on your computer, which explains a lot about why I can’t remember anything.

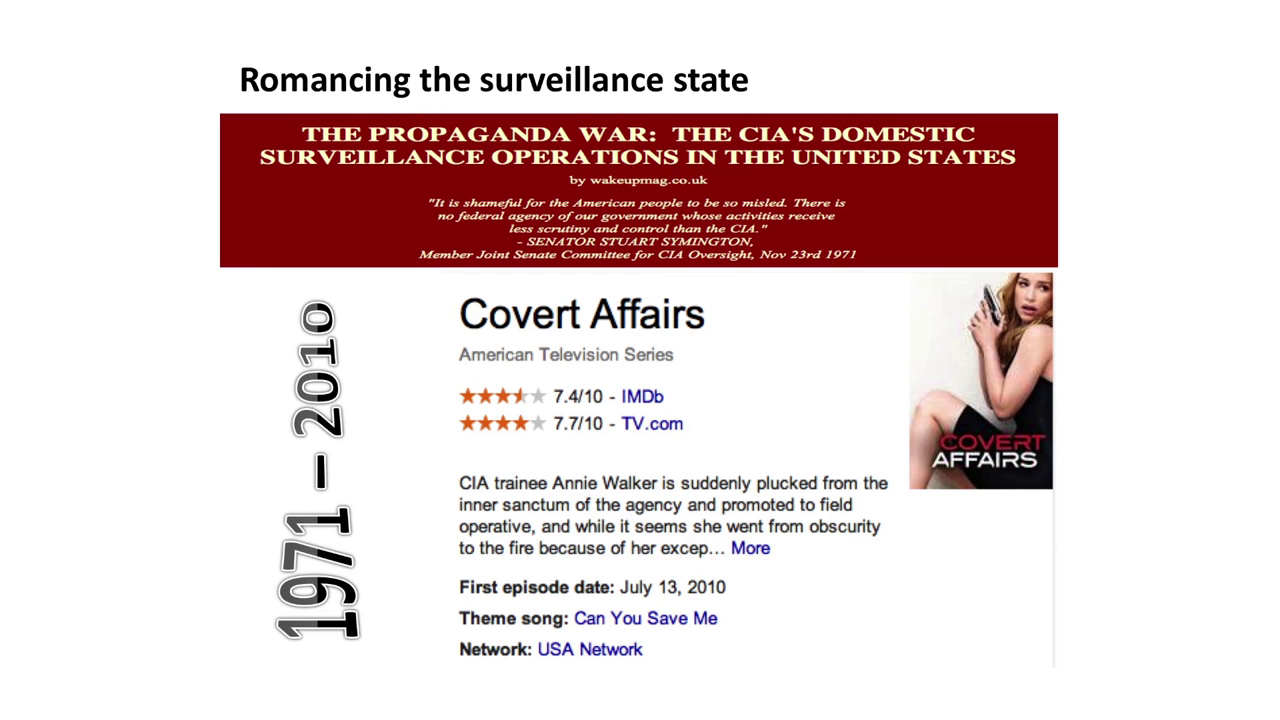

So all of this I feel like there’s just been this gradual…nobody really asks the hard questions, if you do ask the hard questions you’re a Luddite, which I find really offensive because I am so not a Luddite but I really also think that these are legitimate questions to be asking. Are we amusing ourselves to death, basically, with all of this stuff? And I told these guys when we started on Monday that I was going to call my talk “I Blame Television” ‘cuz I do kind of blame television for everything. And I don’t think I’m really terribly wrong about that, which I’ll get to in a minute. But one of the things that’s really interesting to me about TV is that if you look at anything that has to do with privacy, not even just from a government perspective. If you watch the most popular show on television, NCIS, every episode Tim’s hacking into some database or another, or cloning your phone. It’s just become part of the air that we breathe that we assume that A this is possible, B that it will be done, and there’s no hoopla about it.

And you say “well it’s just TV” but TV is an extremely influential medium, as you know. That’s kind of obvious. But it changes the way people think about things. So I have thought for a long time that it would be really fun (and impossible to find out) who actually advises all these TV shows. And my personal belief is that for the CIA, for example, I mean come on:

We have 1971, huge uproar about the CIA conducting these operations, and nobody knows, and it’s terrible. We hated the CIA, right? But not now that we’ve got Annie. And you have to think what happens when people watch. It’s like “Oh, the CIA’s not to bad; she’s cute.” And she runs fast and she knows how to fight. It’s great.

I really wanted to show the opening sequence on a show called Person of Interest. Does anybody watch that? Has anybody seen that? Oh my God it’s so paranoid. It’s about a guy who builds this machine that sees everything. So it’s tapped into all the cameras, it’s tapped into all the phones, it’s tapped into everything, and it can track individuals down to that level. And I just keep thinking “wow.”

The other book that has been really important to me along these lines and is a nice fit with Amusing Ourselves to Death is this book Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television Has anybody read that? Yay! Thank you.

I got interested in this book in the late 80s, early 90s when I’d started a newsletter called “Digital Media“, and the associated conference was called Digital World and it was basically before anybody knew what was going on at all. So people would come together from all these different industries and they would try to figure out how they were going to do business in this new digital environment. And what it ended up being was, there’s a great illustration in one of my Times columns about all these old white farts sitting around a table, and they all had octopus heads and all their tentacles were in each other’s pockets. Which was basically how the business turned out.

I had read this book and I thought you know, interactive media is like television on steroids, and if we’re going to be inventing this new medium should we think about what this one has been and done. So his four arguments why you should eliminate television are: One is the mediation of experience, that humans don’t have direct experiences with things. That you see a television screen and you see the frame and you don’t know what’s going on outside the frame. Then there’s the colonization of experience, which has to do with advertising and how products become more alive than people do. And then the third one is… Well the fourth one is the biases of TV, the inherent biases. And the third one is how television changes us physically, how we interact with things physically.

I thought it would be very interesting to just you know, I bought about a dozen of these books and I seeded all these industry people to try and have a conversation about this. And it was very interesting to me because they were like, angry about it. “How dare you question this dominant medium?” And I thought that what Jerry Mander (which is his real name) what he had to say about this was very interesting. And I think that this, it’s at the end of the book, he said the question he always got asked by everybody was, “Well okay we don’t like television that much either but it’s impossible to eliminate it.” And it was an interesting meditation for me to think about what kind of filter would you have to put on issues around technology to be able to change something that’s so deeply entrenched. And I thought it was really interesting. He really based it in democracy, and looking to see what kinds of technologies actually subvert democracy. And so that center paragraph kind of goes back to what I said about Google. If it’s too complex for a normal person to figure out how to either dismantle it, or in the case of privacy figure out how to not get trapped, then there is no democratic control.

So I just think these things are important to think about, and I don’t see how we get our hands underneath this stuff unless we think about things really out of the box. So, thank you. That’s it.