Geraldine de Bastion: Thank you very much. Wonderful to be back on Stage 5, and thank you very much to all of you for coming and joining our session, which is the penultimate session in our track Cancel the Apocalypse. This track Cancel the Apocalypse is something that’s very dear to the re:publica program team. It’s grown out of a long-lasting collaboration with some wonderful people, including the community and makers of the Utopia Festival in Tel Aviv. And so we’re very proud that we put this program together and especially with our panel today and the four people that are about to join me up here on stage.

We want to talk today about a new movement called Solarpunk and how we’re trying to invent a more positive version of the future. Perhaps you heard some the keynotes in the last couple of days on this topic asking the question why we always tend to think in dystopias and how we can get to formulating a more desirable version of the future. That’s exactly what the people who are about to join me on stage have been doing in their research and the work. And so yeah, we’re going to talk now about solarpunk and going post-post-apocalyptic with four wonderful people. Let me introduce them to you.

Andrew Hudson is a writer of speculative fiction, a thinker on climate, and self-proclaimed solarpunk. Welcome, Andrew.

Steve Lambert is as an artist and activist who’s worked in many countries all over the world with different kinds of people, all of the sort of intersection on topics of society, technology, theater, games, and culture. He’s also the cofounder and codirector of the Center for Artistic Activism. He’s going to be telling us a little bit more about his work there in a bit.

Mushon Zer-Aviv is a designer, educator, and media activist based in Tel Aviv. He’s also worked in different intersections of, like I said, design, interactive design, history, and future, and he’s developed very interesting formats that he’s also going to be sharing with us on stage.

Last but not least, Maya Indira Ganesh has been working also at the intersection of new media, digital technologies, gender, and visual advocacy. She’s worked with Tactical Technology Collective for a long time and she’s now currently doing her doctorate at the Leuphana University in Germany. Welcome, Maya.

So this is going to be the format for this conversation. We’re going to have Andrew give us about a ten-minute input to start with. Then we’re going to join a discussion giving the other panelists a bit more of an opportunity to share the work that they’ve done that fits to this topic. We’re going to have an intervention by Maya. And then we’re going to continue our discussion, and we’re really hoping that you’re all going to join in. So about half way through latest, we want to open it for your questions and comments on this topic, so please be ready for that. And, take the stage Andrew.

Andrew Hudson: My name is Andrew Hudson. These are some of the things that I get up to mostly. I’m a speculative fiction writer; sometimes I call myself a climate fiction writer. I’m currently based out of Phoenix, Arizona at ASU, where I study at the School Sustainability and collaborate with the Center for Science and the Imagination’s Imaginary College. I’ve sort of found my way there by taking interest in this emerging speculative movement called solarpunk.

So, what is solarpunk? I’m going to talk about that today and just sort of set us off so that we can see how this can guide us into some post-post-apocalyptic types of thinking, which I think can take lots of literary and aesthetic forms beyond just solarpunk.

So, what’s solarpunk? The “punk” kind of tips us off that we’re talking about science fiction, right? Solarpunk follows in the tradition of cyberpunk, which was a movement starting in the 1980s to get sci-fi away from these relativity puzzles, and galactic empires, and time machines, and wormholes, and instead talk about the thing that was actually changing the world, which was computation.

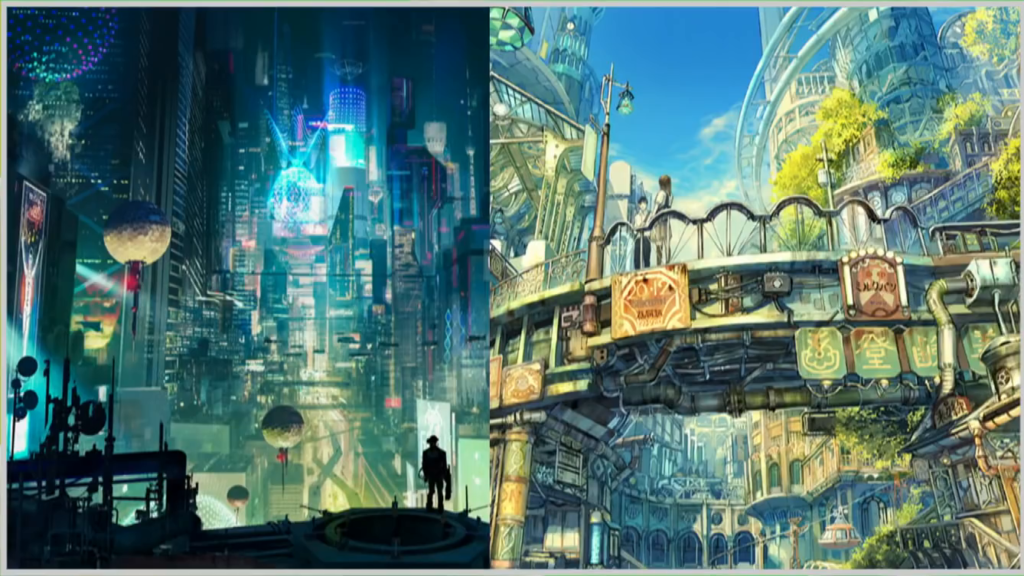

And cyberpunk unlike a lot of movements in sci-fi had this really graspable, coherent aesthetic, thanks to movies like Blade Runner… That’s Neuromancer. That’s Altered Carbon from Netflix this year, and Blade Runner is obviously pretty classic. Cyberpunk wasn’t just a kin of stories and novels, it was fashion and design, and a look and an attitude, all of which was largely countercultural, as the “punk” name implies. So, everyone here can probably see cyberpunk in their head, right? It’s urban and grimy and neon and filled with these dangerous-looking people with metal arms and VR glasses.

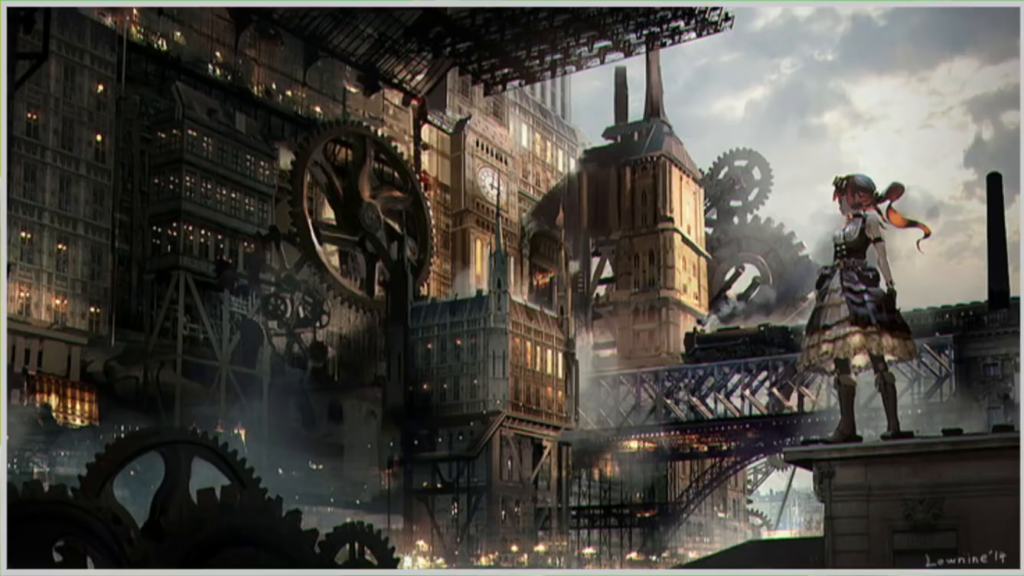

So, there have been a lot of other punk genres, subgenres, that take a line of technological speculation and spin it out into an aesthetic. So steampunk you probably all know, but there’s atompunk and biopunk and diesel punk. But I don’t think any of these quite cohered into a full-bodied movement the way solarpunk seems to be doing. And I think solarpunk in a lot of ways is a response to and a successor of cyberpunk.

Artur Sadlos | Teikoku Shônen (aka Imperial Boy)

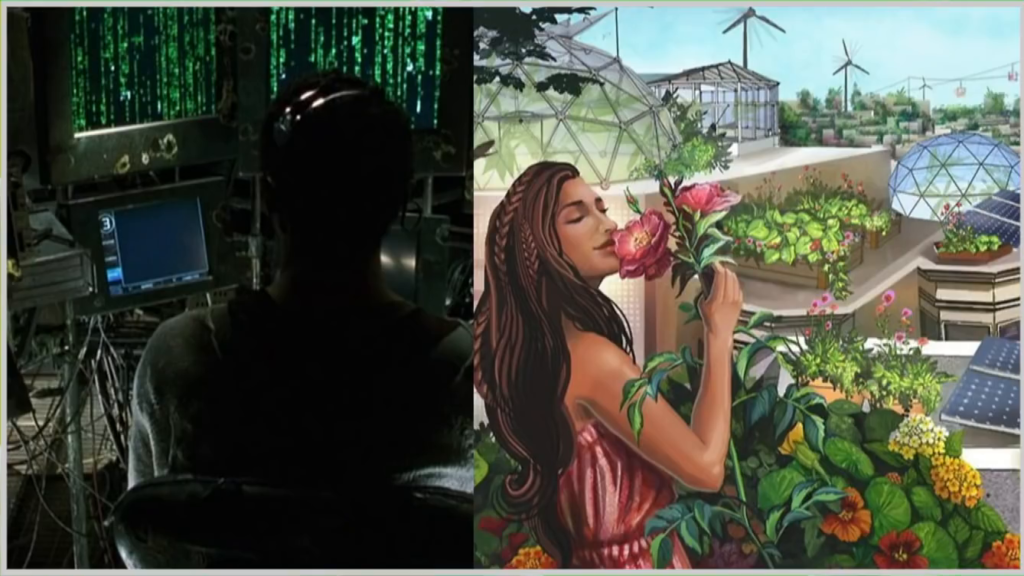

So, cyberpunk is kind of… You know, it’s about the information technology revolution. And solarpunk is about the green technology revolution. Cyberpunk is dark, and chrome, and covered in latex. Solarpunk is sunny and leafy, and dressed in like, hemp canvas, right. Cyberpunk is gritty, solarpunk is plucky. Cyberpunk explores the way technology can shove human life into ever-greater levels of abstraction like cyberspace, whereas I think solarpunk is really about tech that de-abstracts human relationships of material reality, meaning like health, food and water, the climate, the land.

The Matrix | Jessica Perlstein

So cyberpunks, they’re out pirating data and uploading their brains into video games. Solarpunks are revitalizing watersheds, mapping radiation after disaster or war, and bringing back pollinator populations. And since all great speculative fiction is really not about the future but about about the present, cyberpunk is about the politics of the 1980s, right. It was about urban decay and corporate power and globalization. In the same way, solarpunk is really about the politics of right now. Which means it’s about global social justice, the failures of late capitalism, and the climate crisis.

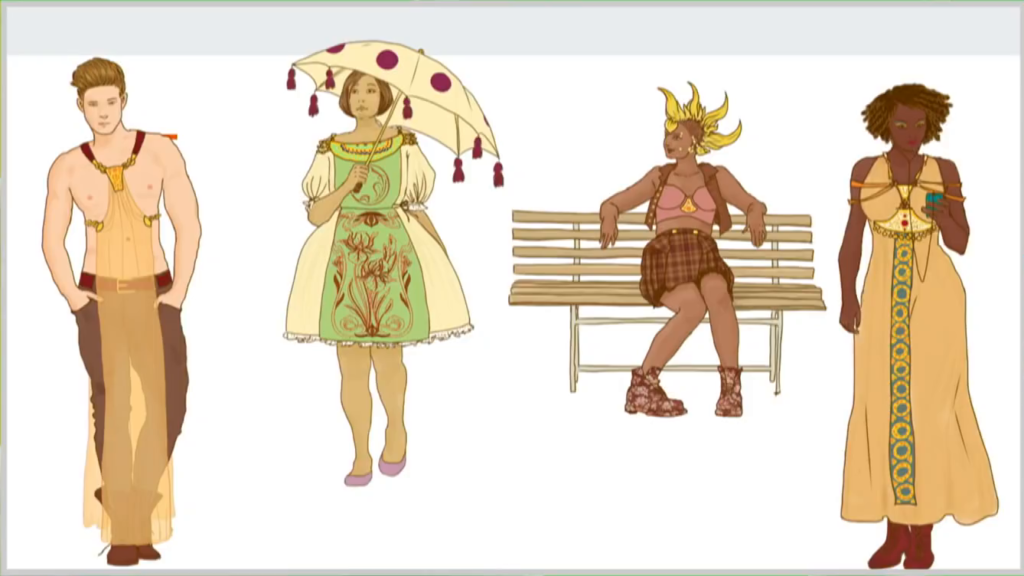

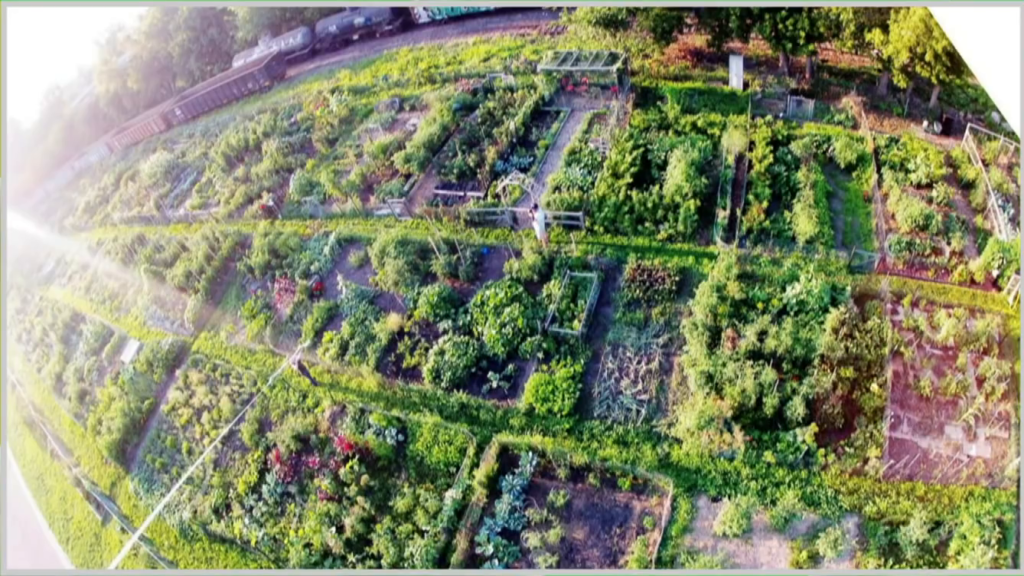

So, while cyberpunk started out as this literature that inspired an aesthetic, I think solarpunk really started out as an aesthetic that implied a lot of amazing untold stories. These were some of the images that were shared on Tumblr and what I sort of think of as one of the canonical founding posts of the solarpunk movement by a user called Miss Olivia Louise. They look super colorful, inspired by Art Nouveau and Afrofuturism. It’s full of greenery, and stained glass, and cultural diversity. The buildings all look really lived-in, but they’re like happily-graffiti’d versions of all these architectural renderings of hotels that have trees in the lobby that we see all the time. And everyone is riding bikes and taking public transit because solarpunk is not just about imagining a beautiful world, it’s about imagining a world that can actually last.

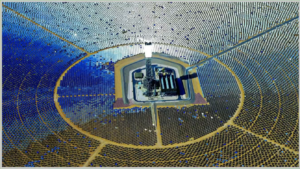

So that’s where the “solar” comes in. These days I think the most transformative technologies are the ones that move us towards a sustainable civilization. Solar energy is really at the front of that pack, and that’s not just me being self-serving because I live in Arizona where we get a lot of sun. Solar has this colossal potential to improve our lives and I think it’s a really profound shift to imagine a technological society that does not run on a scarce resource that’s killing us, like fossil fuels, but that is powered by something abundant and free and life-giving, like the sun.

So this is a solar power installation in California. This is a panel from a comic book about Phoenix in 2045 that was put out by my friends and collaborators at the Center for Science and the Imagination. In the comic, concentrated solar power plants like this one and also this one had solved a big chunk of the energy problem. But now the heat it creates is killing birds, just like this one does, which is having negative impacts on the surrounding ecosystem.

So there’s a lot of potential drama in these renewable energy transformations and a lot of nuance we have to work out, and telling those stories is one of the really interesting things that I think solarpunk can do.

And solarpunk can help us figure out how to make the world on the other side of the transformations meaningful and beautiful. Here’s an image from my friends at the Land Art Generator Initiative. They have these awesome biannual design competitions for big pieces of public art that also generate renewable energy. So this is the kind of thing that… It’s a big solarpunk inspiration and the kind of thing that takes a lot of inspiration from solarpunk.

So, earlier this week I participated in ASU’s solar futures hackathon. I stole the slide from Clark Miller, who helped organize that. We had four teams, and each team consisted of an engineer, a social scientist, an artist, and a sci-fi writer. We worked from a couple of assigned variables, mostly about the size and location of solar panels, to imagine different sci-fi stories in which there’s maybe seven or ten plus terawatts of photovoltaic power generation on the planet. Which is about as much power as is used on the planet altogether.

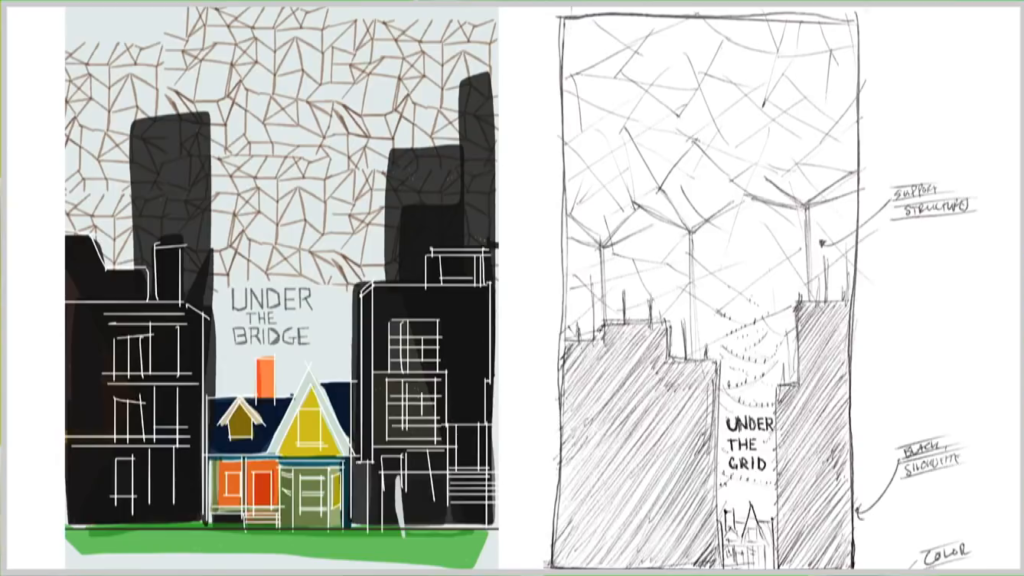

So here’s a bit of draft art that the artist in my group sketched on our first day. My team brainstormed a story about organizing for fair housing regulations in a future Detroit where this city-sized megascaffolding had been put over the city and allowed people to put solar panels and vertical farms in the sky space, kind of the airspace over their homes. So this was a really solarpunk style story, right. It’s got plucky characters fighting to improve a complex political situation in a visually compelling place. I think those are all good elements that you see a lot. No one shoots anyone else (spoiler), and the sci-fi dream at stake is not like, let’s live forever or let’s conquer Mars, it’s let’s save the old woman’s house who wants to fill her skyspace with handmade birdhouses, right.

I was on the team so obviously that’s the kind of story that I wanted to tell. But I was really surprised and pleased to discover that the other three groups were also telling really solarpunk stories. Everyone was imagining communities of resistance where improving solar technology was not about higher efficiency and storage, it was about better systems of generation that were defined as better because they were more just and more free from exploitation and imperialism.

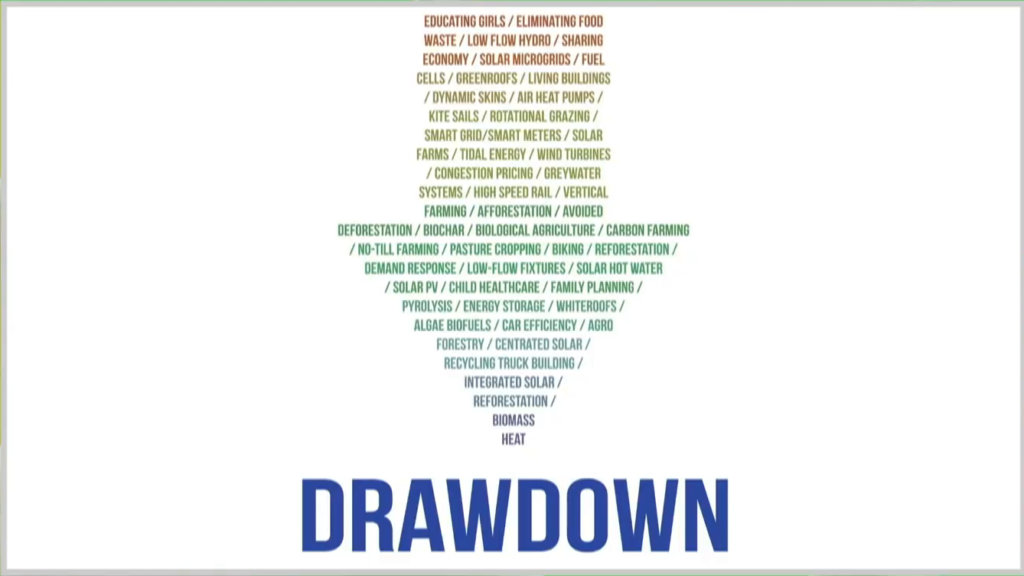

And I think the reverse dynamic is true as well, right. A year ago I saw Paul Hawken premier his Drawdown book—really good; you guys should get it—which quantifies solutions to our carbon waste problem. He argued that investing in education and reproductive health for women and girls would do more to stop climate change than investing in solar panels or wind turbines. Educating girls, it’s right up there at the top. So solarpunk has to be about that, too.

And in the context of apocalyptic, predatory delay on climate change on the one hand, and a lot of people wanting Elon Musk to own every rooftop in America on the other hand, that kind of politics is really countercultural. So that’s why so solarpunk gets to be punk even though it’s not filled with like, cyborg anti-heroes or a lot of people on drugs necessarily. Solarpunk proposes that sustainable technology has a liberatory potential. That growing your own food and generating your own electricity can empower communities to fight back against the forces that would otherwise erase their self-determination and distinctiveness.

I’m a white guy from the US, but a lot of the people most inspired by solarpunk are those who see it as a genre that can tell their stories and give a sci-fi future to people who are non-white and non-Western, who are queer, who are disabled, who are indigenous, who are colonized. And I think that is why solarpunk more often than not ends up being hopeful rather than apocalyptic and dystopian, even though the stakes in the background are actually very apocalyptic in a lot of ways. As Naomi Klein pointed out in her This Changes Everything book, the things we need to do to save the world from environmental disaster are also the things we need to do to build a world that is beautiful and healthy and prosperous and just and that we actually want to live in.

So, Mushon talked about utopias and dystopias as attractors and repellers, right. I want to add kind of a literary framing that I recently heard to that list, diagnostic and curative fiction, and give a name to some previously inevitable human experience. And can also help move us forward by providing a moral framework, or resolving an internal contradiction. And I think this distinction is really important because knowing what utopia might look like isn’t enough to get us there, just like your doctor showing you a picture of a really healthy person doesn’t actually make you feel better. If we’re going to cancel the apocalypse, we have to make some meaningful proposals of what we should do.

So, for me solarpunk says okay, things are really bad. In some ways things are worse than even cyberpunk predicted. Because climate change turns out to be an existential crisis. And because the institutions that cyberpunk worried would take over the world did take over the world but now they aren’t even functioning very well. So let’s give ourselves one out, one advantage, something that we can work with, right. A tool that we can crack into these problems with. Abundant solar power, that’s a good one. One, because we’ll need to capture and dispose of the 500 or so gigatons of carbon waste that we’ve dumped into our atmosphere. And two, because abundance is a paradigm that breaks people out of the zero-sum thinking that makes poverty and deprivation seem unavoidable.

So let’s imagine what it would look like if we made good choices and use that advantage to walk ourselves back from the edge of the cliff, healing the climate, dismantling oppression, and ending the capitalist exploitation that got us into this mess in the first place.

So, again I’m Andrew Hudson. If you ever see a piece of fiction with my name on it please read it. I’ll leave it up to the rest of the panel.

Geraldine de Bastion: Thank you very much, Andrew, for that really nice introduction to what solarpunk means. Very inspiring. Before we kick off I just want to have a quick show of hands, who here saw Wendy Chun’s keynote on the first day? Who saw Steve’s keynote yesterday? Couple more. I’m not going to ask you about Mushon’s because he’s speaking about something completely different today.

Okay, just to get a feeling in the room. So I want to start with a general question to the panel and then give you a chance to speak a bit more about your work. Wendy said something where I thought yeah, that’s actually quite obvious. How are we supposed to develop a positive future if all of our visions of digitization and society are based on dystopian science fiction of the 1980s? And it was like mmm yeah, that makes sense sort of.

So I want to just openly ask you guys why is it that we’ve been working with these dystopian versions of the future for so long? Why is it that the human mind tends to seem to develop more dystopian visions of the future rather than positive ones?

Steve Lambert: Yesterday in the keynote I brought up an evolutionary argument, in that in order to… The story I told was if we heard a rustle in the grass and I was like, “That’s probably a saber-toothed tiger, we should get out of here,” and we did that every time we would live. And if I was super chill and said, “It’s probably nothing. It’s probably a bird or the wind,” I only have to be wrong one time. And I would be eaten, right? And so that all the super chill, relaxed ancestors were eaten. And we are the descendants of the paranoid and fearful, right?

And this served us well for a long time. But it doesn’t serve us now. It gets in the way of us… I mean, also in our culture there’s a lot of rewards for pointing out problems, right. If you can point out problems and draw connections between them and study them in a way that no one has before, and speculate about other problems, you’ll be in the op-ed pages of newspapers. You’ll be written about as a great thinker. You’ll be asked about your opinion. You’ll publish books more easily. Sorry, Andrew. So we reward this, right. We think that that’s insight, is to see how bad and explain how bad the problems are.

de Bastion: Yeah. And I mean, fear is one of the driving forces in most political government narratives today, especially your government. [to Andrew Hudson]

Lambert: It works.

Andrew Hudson: Yeah, I think, though, that we’re all pretty tired of the fear, right? I mean, it doesn’t actually show us a way out, you know. You’re all running in different directions. It doesn’t coordinate you. And you [to Zer-Aviv] were making that point yesterday. So having something else is really valuable.

Zer-Aviv: And the other side of the argument is also true. Like, if you actually say what you think should be done, you’re really putting yourself on the line. Like, if you’re saying “we should do this,” then you’re setting expectations and people are very concerned about that. And then if what you said should happen, or what you said we should do, doesn’t work exactly like you wanted it to work, it’s all your fault, right? But if you just said that this is a problem and it ends up not being a problem…no problem; that’s good.

Lambert: And pointing it out is what helped us avoid it, right. Like you’re given credit for highlighting that hazard so everyone could work around it. But I think talking about our dreams and hopes for the future makes you sound like a dreamer. And that’s also not valued, right. It makes you vulnerable.

de Bastion: Also our present, there seems to be very little in between. I mean, most… It’s either this way or this way. So either you go to a tech event and everything is very dark and there’s usually a bunch of activists terribly concerned about the very dark present—not just future—that we’re living in, which is surveilled and full of terrible IoT devices, etc. Or you go to a tech event which is super positivistic and celebrating all the pseudo amazing startups that they have on stage. But very very little in between.

Maya Indira Ganesh: Yeah I mean, I think that both those things are true. And I’m not going to go into the politics of sort of events and how they’re set up. But it’s true that those extremes are there. I think there’s the evolutionary biology argument, that kind of approach to thinking about why we like to tell certain stories. I’m much more of a kind of political economy materialist activist, so I’m interested in who has the power to tell the stories and what kinds of stories are being told at different points in time. These are all very situated and very specific. And I’m pretty sure somebody’s already looked into, in the 70s, for example, or 80s, when a lot of the cyberpunk or dystopian narratives were being produced, what were the other five published novels in the SF genre, for example. If somebody knows about that paper which has looked at that, please talk about it. Otherwise there’s a great digital humanities project out there for someone to do.

So it’s like, which stories get told? So for example if you look at the literature in science fiction of feminist SF writers, for example, maybe they were telling other kinds of stories. People like Octavia Butler, you know, who were not known for many years. And there are many others who continue to be. And I find in some of those stories this kind of struggling with power, and struggling with new and different changed realities. So maybe there are just other ways of telling the story, and those were not amplified, and they set the stage, and you know.

de Bastion: Let’s get personal for a moment. When did you guys decide to tell the positive story? Were you all very concerned, dark thinkers, and there was a point that you said, “No, I want to start working with utopias as a method,” working with them. I like that you called solarpunk a movement and not a genre. So this sort of empowering feeling that you’re a part of actually doing something.

Hudson: Yeah, I use the word “movement” because I actually think there’s way more people doing solarpunk than writing it. Which is really eerie for me as a science fiction writer, to constantly hear from people who are like, “Oh yeah, that stuff you’re describing is what we’re actually doing, where dropped out and made our permaculture commune. We’re creating makerspaces that are totally transformative…” And so yeah, I think “movement” is a much better word because it encompasses activism and political demands, not just art.

Zer-Aviv: Yeah, for me it has to do with living in Tel Aviv. Which happens to be in Israel. Which happens to be um…not the most hopeful place in the world right now. And you know, you can put it aside for some time but then I also have a son. And my son is seven years old. Which means in eleven years, he’s supposed to be drafted. So I have a timeline to work with. That’s the way I see it. And it became really really depressing for me. Like it made me feel like I see no positive prospects for the future.

And I love Tel Aviv. And I love my son. And I love my friends and my life and family where I live. But I also know that the state of this country, and the state of the occupation, and the state of so many things that are happening in Israel are just unsustainable. So it’s either that I resign from everything that I know, or I actually shift the way that I think. And for me the idea of going beyond that depression is existential.

I also think it’s a matter of humility. I think there’s something very pretentious about being so depressed.

de Bastion: Yeah.

Zer-Aviv: Like…what the fuck? Like, there are so many options. And we need to kind of embrace them and be a bit more humble and understand that the future is not written. It’s not like it’s written and you just you know, drift towards it. You actually make it.

Lambert: Uh, just a defense of depression, really quick. I think one of the reasons people are reluctant to imagine these futures is because if you really do and you vividly paint a picture in your mind of the world that you want, it is in such contrast to the world that we’re in now? And to know how big that gap is… You know, I think like there is some comfort in not really being able to imagine how good it could be. Right? So there’s that part, and I think that we…protect ourselves sometimes.

But the way that I got into this is not… You have a very specific situation, I’m really glad you said that. But for me it was watching audiences, and I know you do this, too. And audiences don’t respond to… I mean, I actually think it’s kind of insulting to be like, “Do you know how bad it is? Like do you even realize…? Like let me show you the data just on how bad it is, because I don’t think you know.”

And then the idea’s that once you know— That the reason you’re not active is because you don’t know. And if you did know these things, then you would be motivated. And when you’re not motivated after you learn it’s because there’s something wrong with you. You’re a bad person, you’re uneducated. Right? And then this is how activists get bitter, is they start to resent the people that they’re trying to change for not having this enlightenment, revelation, that turns them into a force, right. But what does motivate them? The possibility. Its what’s motivating you, right?

Ganesh: I think for me, yes I worked in technology and information activism for a long time and I still continue to be that person. But I think that an experience of growing up with kind of like, fragility every day, when you know that things kind of turn on a dime— I mean, I actually grew up in a place where there was a wall. One side of the wall was the very kind of comfortable, academic, fairly cosmopolitan small town in South India, and was an academic university town.

And like right on the other side of the wall were all of the people who worked in our homes and lived in poverty. And they were part of community health projects that the hospital did. And you went to the same school and you had the same experiences of people on the other side of the wall but they— I mean, in school you have the same experiences. But they were different and you could see how… I think when things are fragile you kind can’t let go, and I think that resonates with what you’re saying. And so I think that’s always been there for me.

And recently I think my work has sort of turned more to the urgency of what does it mean to inhabit this planet, in a more sort of academic or intellectual sense. And I’m quite happy for that and I will talk a little bit about those experiences later but I feel like something is coming back for me. Like how do you kind of sustain and work through living in fragility or with fertility.

de Bastion: Yeah. Let me dig a bit into your workspaces. Because I was told, Steve, that at the Center of Artistic Activism you’re using utopia as a tool, as a method, in different workshops that you run. Can you tell us a little bit what that looks like?

Lambert: Yeah, so I would sort of say there’s two parts. One is with the activists themselves, or the artists. We work with activists and artists as like, how to use what we call like utopic visioning process for them to really get access to what they truly care about and what’s motivating them, right.

So, one of the things that we’ll do is we’ll… We were working in South Texas and we were like, “Okay, what would be a win for you? What would be success?”

And they’re like, “Oh. You know, if we could pass State Bill 17, that would be huge.”

And we’re like, “Okay. Imagine you pass that. What would you want to do next?”

And they’re like, “Ha ha ha ha…no.”

Right? It’s like they can barely imagine that. And we’re like, “No no, seriously. You did it. What would you want to do?”

And they’re like, “Oh. Well, we would need to enforce it.”

Right? It’s just like, the most the minor, small steps. Like okay, you passed, you enforce it, you’re doing great. What would happen after that? And literally they’re like, “Um… Can I pass?” They’re so… And you have to be to be an effective activist, like realize what the next step is and be fighting to get that.

But as we pushed and pushed and pushed, right… Actually it’s kind of funny. What so many people around the world describe is what you have shown in that solarpunk vision. They describe a world that has this like, lush green atmosphere, there’s leisure outside. You can find kids playing and people are talking and communicating with each other and you smell great food, and it’s like, a beautiful vision of what they want. But they’re not in touch with it, right. So part of it is getting them in touch with that, and then learning how to use that to reach other people. And then using that as a goal-setting process to figure out their plans

Hudson: Yeah. So, that is totally the shared, kind of utopian vision. And I think what’s interesting about trying to approach it throughout a counterculture-style genre like solarpunk is, say that like what’s happening there is contested, right. And getting to it is contested. And it’s not necessarily going to be shared, and equitable, and it can look really good but it might not be good unless we have sort adjusted our social arrangements around that, too. So sort of seeing through those visions into the actual debates that need to be had and the politics of it.

de Bastion: And I…I hope you’re going to agree because I think it’s high time that this kind of idea starts becoming more popular, talked about, propagated. I have been in the situation often where speaking about automation and the future of work, and this sort of very dire picture of the future is painted where everybody’s going to be enslaved by their robot boss—or out of a job; it’s basically either or. And whenever I try to sit there and go, “But guys—or girls—what about this idea that there could be a new sort of rising of the arts and the humanities that we saw after the Industrial Revolution? Perhaps there’s an unleashment of creativity and sort of putting together our energies to create more beautiful things.”

And most of the time, especially— I mean, in Germany you get a lot of people looking at you going [mimes a condescending stare] as if you’re like, the naïvest person in the world. So I think this is something that’s very powerful and very necessary.

Lambert: There’s a lack of imagination that goes along with that kind of disasters thinking. Because I would argue that automation is only a problem like you’re describing under capitalism.

de Bastion: Yeah. I mean, there’s a great sentence that was said by our closing keynote speaker of day one, Sascha Lobo, that a lot of the things we’re blaming on digitization are actually problems of capitalism that we’re blaming these digital technologies for, but— [clapping in audience] Yes, I think that deserves another round of applause. [more clapping] Quote Sascha Lobo on it, not me, but I thought that was an important sentence to say.

Mushon, you work also designing visions of the future. I’d like to invite you to share a little bit about some of the methodologies that you’ve created. I’m sure a lot of people especially in this city experience the sort of historic touring that you can do in Berlin. There’s a lot of places where you walk past a column, and you can press a button, and then you’ll get information about the history of that place and what’s happened there. And there’s also some really great apps that you can walk through the city with and will show you pictures of what paces looked like GDR times. So you sort of played a little bit with that idea.

Zer-Aviv: Yeah, so twelve years ago I started playing with this idea of audio tours. We did a project called “You Are Not Here.” It was a tour of Gaza through the streets of Tel Aviv. We made a tourist map of Gaza, and on the back of the map we printed the streets of Tel Aviv.

Now, when you held them up to the light you could see the streets of Tel Aviv through the streets of Gaza, in 1:1 ratio. And let’s say you want to visit the Unknown Soldier statue in the heart of Gaza. You find the corresponding location in Tel Aviv, you actually go there, and you find a sticker in the street. The sticker had a telephone number and an extension. You call the telephone number, you enter the extension, and you get an audio tour of that corresponding location in Gaza, written and narrated by Laila El-Haddad, a Palestinian blogger who chose all of the locations and recorded them.

And the project was very well received. And the most exciting feedback that I got about it is someone came to me after one of the tours and she said, “You know, for me, I love Laila’s stories, and I love the way she narrates Gaza. And she obviously loves Gaza a lot. But for me the strongest part of the tour was when I was walking from one point to the other. Because then I was walking along the boulevard in Tel Aviv, and I was trying to imagine all of the buildings being the buildings in Gaza, and the people walking across from me being the residents of Gaza.” And that was a transformative moment for me, that moment of “what I see in my imagination.”

And and I said okay, there’s something here. I have to figure it out. And then you know, it was… We started this project 2006, 2007. And then smartphones came. And then it’s like everybody has devices in their pockets. We don’t need to make sure that the stickers are still in the street all of the time.

And then a year ago, so, like a year and a half ago, I was invited to do a new project in Jerusalem. And I said okay, great, let’s do you You Are Not Here in Jerusalem. And I’m thinking which city should I overlay over Jerusalem. And I’m thinking about it and I’m like, Jerusalem doesn’t need another city overlaid on top of it. Jerusalem is already a city, on top of a city, on top of a city. And it’s like, the levels of narratives that are fighting for existence in the city are just unbearable. It doesn’t need another one.

But all of these narratives are based in the past. I lived in Jerusalem for a couple of years as a student. It felt like the past because is kind of dragging you down. You can’t even experience the present let alone speak about the future, which is like super scary. If you just start speaking about the future in Jerusalem it’s like aaaaah.

And then it was obvious. We need tours of the future, rather the futures in Jerusalem. And it cannot be one. It’s not like in the case of Your Are Not Here, it has to be plural. So we turned to a group of authors and invited them for a workshop where we used some techniques that I spoke about yesterday like forefutures and backcasting. And they created different speculations.

And I want to give you just two examples. We have eight tours. One of them is [Hagit Geysau sp?]. And the spot that she chose in the city is the Daoud Brothers building. This is one of the unique cases where Palestinians who had to flee in 1948 managed to win their property back. And the building came back to the ownership of its original inhabitants. So it was a real story that she wanted to tell. But then she she kind of took it into the future and we’re arriving at this building, and the woman who who lets us is from that family that got a hold of the building. And now apparently the whole region has collapsed, and the building that has become something you run away from becomes a place you run to, because it became a shelter.

Also some solarpunk motives there, with kind of biodiversity and kind of maintaining seeds and stuff like that. But there’s something like a mix of a post-apocalyptic decay and then this hope in this one place. And I love that story, but then it’s repeated, that thing you know, let’s create great things after the apocalypse. And I felt like, good, that’s one future. Hopefully we’re going to get others.

And another tour was by an emerging political organization called Two States One Homeland. They’re actually going against the two-state solution that has not been really proving itself. And they’re saying no, we don’t need separation, we need to live together. We need to have two governments and we need to open borders. We need a confederation, basically, between Israel and Palestine.

And I was like okay…right. But then from that framework of really challenging myself I went like yeah. Let them… How does it look like? And then the location that they chose is very interesting. They chose the village of Silwan. The village Silwan is a village in East Jerusalem, and it’s very contested because the settlers that are invading that village are trying to push the residents out of that village. At the same time there are also archaeological projects to study the history of the “City of David,” where apparently historically that’s where King David’s court used to be. And it’s a whole settler project to kind of argue for the history… for the Jewish right to the place.

Now it’s true, apparently, that that’s part of the history of the place, but while they’re doing that they’re also wiping the Palestinian history of that place. In the future that was proposed by two of the founders of this movement, this specific site is becoming a shared archaeological site. And both Palestinian and Israeli archaeologists are working on finding the different histories of that specific place. So beyond the fact that it’s really exciting to hear that, and…you feel a bit guilty about enjoying it because all of your defense systems are going like, “No, noooo, it can’t happen,” and like, no no, I want it to happen. But I want it to happen so let’s figure out how to get there. And they’re not only looking at plural futures, they’re also looking at plural pasts. So there’s something about placing that option of utopia—and this is the most utopian of the eight tours—that is really powerful. [applause]

de Bastion: It’s a super interesting format I think you’ve developed. Before we discuss that a little bit and open the floor for your questions, I’d like to ask Maya… She’s prepared a little intervention for us, and I think it’s a great time to hear that.

Ganesh: Thanks. It’s not really an intervention. I’m not gonna make you do anything. But yeah. It’s an intellectual intervention. Yeah, it’s just a presentation, it’s a regular presentation.

de Bastion: I thought I’d give it a cool name.

Ganesh: I’ll tell you a little bit of the background to my intervention or contribution to this discussion. So last year when Republica had an event in Thessaloniki, Republica Thessaloniki, Mushon invited me to do a little presentation with him. And he talked about some of the things that I think he presented here. And I had just come back from something called the Planetary Futures Summer School, which was actually run by Orit Halpern, who was also a keynote speaker here a few days ago. And Orit is a pedagogue, and academic, and a mentor of mine.

And so the Planetary Futures Summer School took place at Concordia University and there were about twenty of us PhD students who looked at themes of extraction, colonialism, and speculation to ask about what does it mean to actually inhabit the catastrophe. And what happened in that time was I found myself taking a lot of photographs, posting them on Instagram, wherever there was a connection, because we were kind of in the rural north of Canada for a while at an open pit gold mine where you actually don’t have Internet connections. And so we were encountering things like gold mines and waterways and thinking about our connection to the planet itself.

So I was taking all of these photographs and then later I kind of put them together as a story on Instagram and then I made that into a presentation that we did in Thessaloniki. So this is… Well, I didn’t have enough time for the story here, but I thought I’d focus on this idea of exit, and this is particularly inspired by the work of Sarah Sharma, who’s also an academic at the University of Toronto. And her work is really about a feminist perspective on the idea of exit and the way that exit emerges in our narratives around speculation, utopian, and dystopia. Who gets to leave? And why do we want to leave? Who are the people with the capacity to leave?

So for example, we hear a lot about Elon Musk putting a car into space, or wanting to terraform Mars. Google having its Lunar X Prize and wanting to mine the moon. There’s even a film from 2011 called Another Earth—it’s a really bad film—but the plot in the film is about how there’s actually another version of Earth out there. It’s a complete replica. So it doesn’t matter what you do here, because we’re going to go to another Earth anyway and we’re going to start over there.

So these sorts of ideas about starting over and exiting and going somewhere else are actually inherently colonial because this is kind of what happened in a lot of colonial times as well. A lot of countries that eventually became colonial rulers and masters were facing situations of crisis and had to go somewhere else to shore up their economies and to develop more spaces to extract natural resources. So going to the moon is a little bit colonial in that sense. And the story that I wrote from the Planetary Futures Summer School was about actually a scientist, a woman scientist who’s elite and gets to go to the moon and work there, and is ruminating on this idea that you know, why did she get to exit? Why did she get to go and be a colonialist and start over. But felt good that the work she was doing on the moon was actually helping people back on Earth.

So the thing is this is not so speculative, actually. The European Space Agency does have a moon village project. It’s a very real thing. And they’ve been doing workshops with artists and architects and designers to try and imagine how we might inhabit the moon. But also talking to social scientists and humanities scholars and artists about how will we deal with society on the moon? And it’s almost as if none of us are looking at these questions now here on Earth and as if we have to deal with them for the first time again on the moon. Except that there are actually…outer space and the moon is kind of legally…there are black holes, and we don’t know how to actually negotiate relationships in places like that.

The other thing where I also see these ideas of exit and who gets to exit is in things like transhumanism, or the idea that we can edit genetic code. It’s this idea of kind of escaping time, escaping the body. And it’s seen as “hacking,” and I think hacking it is a positive thing. Or the use of genetics. Like I want to show you something I read about CRISPR. And CRISPR is gene-editing technology. This is a quote from Bill Gates writing in Foreign Affairs.

For instance, sophisticated geospatial surveillance systems, combined with computational modeling and simulation, will make it possible to tailor antimalarial efforts to unique local conditions. Gene editing can play a big role, too. There are more than 3,500 known mosquito species worldwide, but just a handful of them are any good at transmitting malaria parasites between people. Only female mosquitoes can spread malaria, and so researchers have used CRISPR to successfully create gene drives—making inheritable edits to their genes—that cause females to become sterile or skew them toward producing mostly male offspring.

Bill Gates, Gene Editing for Good, Foreign Affairs May/June 2018 [presentation slide]

Of course Bill Gates and the Gates Foundation has been doing a lot of work on malaria, not all of it very successful. But I found this paragraph really interesting. So using sophisticated geospatial surveillance, computational modeling, and simulation—all high-tech stuff—to then identify where malaria outbreaks are, and then edit the genes of female mosquitoes because these are the ones that transmit malaria and create mostly male offspring, which don’t. And that’s all great. And I think it would be awesome to eradicate diseases like malaria, except that we have to go back to kind of older questions about who controls this technology and what does it mean when you can go into a place and like, change the ecosystem by just producing more male mosquitoes as a solution to a problem that it’s not like people haven’t been working on these problems.

So these are kind of other ideas of how we might want to exit the problems that we face. So recently I was in a presentation about work by Anna Tsing, who’s another wonderful academic and has worked closely with Donna Haraway. And she’s working on a new project at the University of Copenhagen that looks amazing and I’m looking forward to when it comes out. It’s called The Feral Atlas. And I was hearing about it a few weeks ago and it’s based on this idea that the planet and the climate that we inhabit is not uniformly bad. They are not uniformly experiencing devastation in the same way everywhere. And there are these effects that we’ve had on our planet where there are patchy outbreaks of feralities—is ferality a word? Maybe. Or feralness maybe. And the question they posed is what happens if you embrace the horror, and you actually embrace the shock.

And one of the things that’s going to be part of that project is this. And many of you probably know this image. It’s by the photographer Chris Jordan and it’s called Midway: Message from the Gyre. And it is a picture of an albatross which he called Shed Bird, and this is what is in the albatross’ stomach. And we have to face our effect on the planet through the picture of this bird.

So, the Feral Atlas project asks, what happens if you actually stay with the horror and the shock, and you don’t exit, and you don’t leave? What happens then? How do you face the propaganda, the disinformation, the shit and the violence? How does your strategy change and what are your tactics? And I think a lot of the great projects people have been talking about here have been about doing the old, boring, mundane stuff of kind of finding ways to inspire ourselves to stay with the trouble.

And so I want to end with two stories of very different context about women in India and Pakistan who are actually dealing with conditions of restricted mobility and violence in their city. So the first is Girls @ Dhabas. A dhaba is a tea stall. So this is a project out of Lahore, and it’s about women riding bicycles, hanging out in tea shops, and drinking tea. Which is the most, mundane boring activity if you’re man who already owns public space. But if you’re a woman, what does it take to actually embrace that fear and that horror of saying no, I’m just gonna hang out and you know, drink tea.

Or there’s Blank Noise from Bangalore, another wonderful group of people who they call themselves action heroes. And they do really mundane stuff like this, where if you’ve been to India you know it’s very common for men to just…first of all occupy a lot of public space, but also do stuff like sleep in parks. And you know, especially in a city like Bangalore where you have amazing parks, it’s one of the nicest things to do. But you are not going to be an Indian woman sleeping in a park in the middle of the day. That’s just…that’s too dangerous. So they encourage each other to actually just take naps in parks, and that’s all you have to do—it’s as simple as that.

And I continue to go back to these kinds of examples where you have to kind of feel things and be new and different things, with and in your body, and basically not exit and just face the shock and horror. Thanks. [applause]

Geraldine de Bastion: Thank you. Thank you Maya. I want to open this up for questions from you guys. Can you do us a favor and, unless you’re sitting in the first row please come to the middle Oh no, lights. Alright then, never mind what I said. Pavel, would you like to go first? There’s a microphone coming your way.

Audience 1: So, good morning. My name is Pavel. First I wanted to thank you, because I think that this is a really huge thing and we should be creating new visions for the future. And I wanted to ask exactly about that. Because in the very first notes toward a manifesto of solarpunk, it was stated that it should be a movement for more than just the white West. And when I’m talking to people from outside of Europe, outside of the US, I find they still follow the dreams that they are sold by the neoliberals, the transhumanists, and the cyberpunks. And I was actually talking to an Egyptian maker who is basically implementing all the solarpunk ideas, and he was openly stating that he wants to bring the cyberpunk future. Because for him this was the future. So my question is, how can we actually approach people from different cultures. From Africa, both North Africa and Middle East, from Sub-Saharan Africa. From Asia, South America. How can we encourage them to create their own narrative in the framework of solarpunk, of sustainability, of working cross-culturally, without giving up your own identity? Thank you.

de Bastion: Thank you.

Andrew Dana Hudson: Yeah. So, the notes towards a manifesto’s written by my friend Adam Flynn and you should all go read it. But yeah, you’re totally right that this is sort of a setup that’s really meant to be a jumping-off point for a lot of other types of futures that aren’t just solarpunk futures but are indigenous futures, and afro futures, and disabled futures, and much more about trying to give futures to people that have been erased from so many of the stories that we’re told about who’s going to be on Mars and what their culture is going to be like. I mean, even things like Star Trek, which notoriously has a lot of diversity in it. There’s lots of people in that don’t get to be in the 24th century. So, I myself just want to courage people to go out and figure out how to tell the stories of people that previously didn’t get to show up in a lot of those visions.

Mushon Zer-Aviv: I think another answer is like, what Maya just showed. Like that picture of women sleeping in the park really looks similar to what Andrew was showing in his presentation. Like, apparently there is something shared about what we value. Obviously there’s—and I argued that constantly about the need for plurality in the way we’re thinking about futures. But there’s also the need for mobilization, and collaboration, and common ground. So I think there’s room for these things to happen, and they’re not necessarily… Correct me if I’m wrong, but I understand that solarpunk did not start in the “Western world,” right? It developed…Brazil was an initiator there and so on. So I think we’re channeling a lot of ideas through stages like this one, which is not in Brazil, but this is not the origin, we’re just a channel.

Maya Indira Ganesh: I just think that people are also kind of making their futures. It’s maybe not about us…I don’t know who us is. There is no uniform “us.” But just, it’s not about us taking or sharing those ideas. I think some of those narratives and practices may already be there, and it’s a question of do they get infrastructure or other kinds of support to sustain those things. And maybe the bigger question that I’m always left with at the end of these discussions is about scale, and what is our notion of something scaling for it to be successful? Maybe some things have to happen on a small, local scale. A lot of ideas that we have of speculation are about landscape, huge landslides of change, you know—and maybe it isn’t always like that, and the small, boring stories that continue to happen that are significant.

de Bastion: I’m sorry those of you still raising your hands but we’ve run out of time, and—

Zer-Aviv: The meetup.

de Bastion: Exactly. Exactly, Mushon. I was just going to say but, you are still going to get another chance to ask your questions and meet these wonderful people who I’ve had the privilege to share this last hour on the panel with. Because like I said this is only the penultimate session in the Cancel the Apocalypse track. We have a meetup coming up. And it’s going to happen, what better place could we have wished for, in the outer area of the maker space. So if you follow all the way through the Stage 1 hall to the back of our networking area and outside and you see this black [faberville?] bus… Which is also a little bit of designing the future. They’re going around to places which are sort of no jobs, dire, impoverished, and showing kids how to make cool stuff. And so we thought that was a great place to meet up for the Cancel the Apocalypse meetup, where we’d like to meet with you guys who are out there designing these positive futures or just have more need to debate these topics, and continue the discussion there. Thank you so much for coming and joining this panel, and thank you so much Mushon, Andrew, Maya, Steven. This was a great discussion. Thank you.

Further Reference

SolarPunk and going Post-Post-Apocalyptic session page