James Bridle: Thank you all very much indeed for being here. I’m going to talk a little bit about my interest in this, and also some thoughts, essentially, about these connections between borders, bodies and technology that kind of it turned out the exhibition was about. The process started from really a long while back with an older project of mine which I’ll explain, that should give you some idea of why I’m interested in this area and what I think is kind of interesting about it.

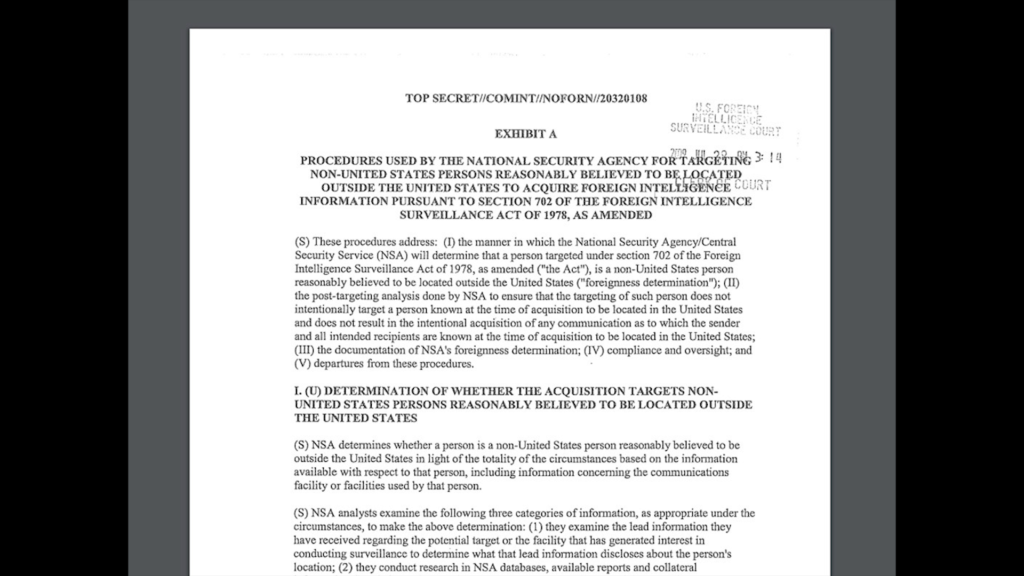

And one of the places this research started was with this document. This was a document that was revealed that came out as part of the Snowden revelations, the big leaks in the NSA in the US. It’s not one of the most kind of spectacular pieces of information. It wasn’t one of those kind of like, eye-searing PowerPoint slides that everyone saw of kind of horrible graphic design that was all about spying on you and all of your information. It’s something a little more kind of subtle but I think more interesting.

The job of the NSA, and of pretty much all national spy agencies, is to take in all information they can possibly find out about you, and about everybody in the world. But it turns out that they actually have some rules about this. It’s very unclear if anyone follows these rules. But the rules exist. And one of the rules is that most spy agencies—foreign spy agencies—aren’t supposed to spy on their own citizens. So in the case of NSA, they’re not supposed to spy on American citizens.

The problem is, if you’re like slurping in all of the information on the Internet, which is what they’re doing, how do you know who’s an American citizen or not? How do you decide whose data you can use?

And the answer they came up for that as described in this document is that they basically look at all those data points, and they say, “Well this person behaves like this; they visit this website; they do this thing. So there’s like a 60% chance they’re American,” right. Based on that data. And if it’s over 50%, you get assigned as an American. And they say…[shrugs]…they say they don’t look at your data, right. That’s their claim.

If you drop below that 50%, then you’re fair game, right. And they’ll study you. They’ll record all your data. They’ll put it in vast databases and use it for the things that they use it for.

And there’s something very strange about that. Because the right to be surveilled, or to not be surveilled is the right to privacy. And the right to privacy is something that’s enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a fundamental human right. Your right not to be spied upon.

And we know countries um…don’t always respect that. And the NSA and other spy agencies definitely don’t respect that. But it is, supposedly, one of these fundamental rights that you have. And it’s a right that descends from your citizenship. Citizenship, after not thinking about it for a while, feels like something we’re all thinking about quite a lot these days. In the words of Hannah Arendt, the kind of great political theorist on this area, citizenship is the right to have rights. All of your rights essentially descend from your citizenship, because only countries will protect those rights. Only your own government, essentially, and your government embodied in the passport you hold, will protect you from the violation of those rights.

But in this case, the rights aren’t being decided by the passport in your pocket, what particular documentation you hold. It’s being decided by this piece of software that’s automatically interrogating all these points of data and saying hey, this person is this or this person is this. And that has a fundamental effect on your rights, and therefore produces in kind almost a new kind of citizenship where your citizenship, which is essentially this framework of rights, isn’t decided by your passport. It’s decided by the data that you leave kind of strewn around as you’re on the Internet and the operation of this software that nobody really sees.

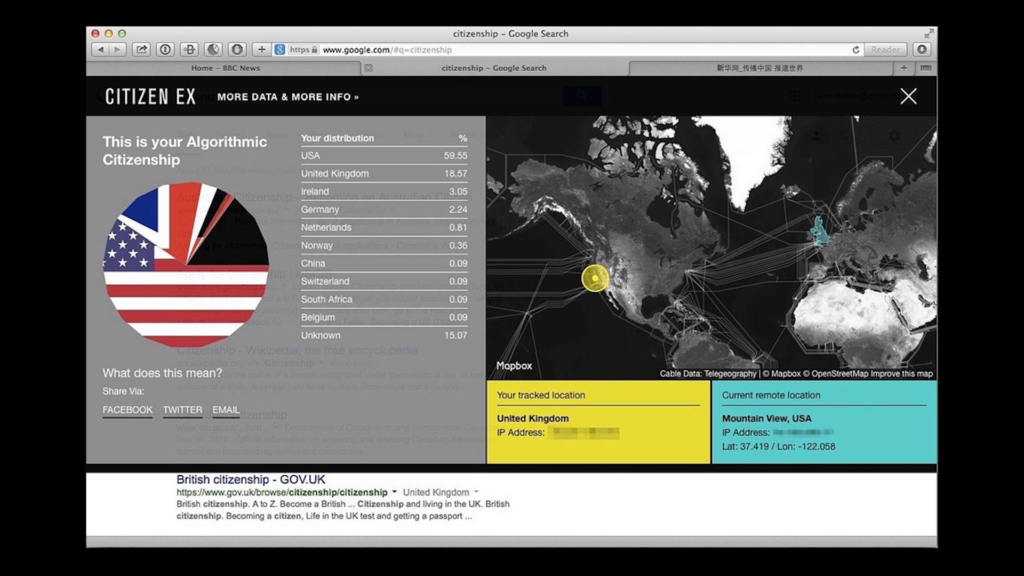

And I found that idea to be completely fascinating. And so I built a thing called Citizen Ex, which is a a piece of software that you can download and run. And it runs in your browser. In Chrome, Firefox, Safari, whatever you use. And it tracks you browsing. It does this, to be clear, incredibly privately. It doesn’t share the data with anyone.

It turns out that’s really hard to do, by the way. The way these pieces of software are designed, they’re kind of designed to share all of your personal data. To build something that doesn’t share your data takes a huge amount of extra care and attention. Which is not to blow my own trumpet, it’s just point out that it’s not the way this stuff is supposed to work.

But this thing tracks your data, and it shows you particularly where the web sites that you’re visiting actually are, right. Because we tend to have this thought of the Internet as just being this kind of like big, cloudy place, right. But actually web sites are pieces of data that are stored on servers in particular places. And those places are in other countries. That have different legal jurisdictions. That maybe have different laws associated with that data. So if you start to think about these web sites as being places that you visit, rather than just places you get data from you, can start to build up this thing which we call an algorithmic citizenship. This is a lot less sophisticated than what the NSA are doing, but over time as you spend time on these different web sites, you can actually start to visualize hey, today I’m like 60% American and I’m like 40% Croatian, or whatever it is. What is the picture of me that emerges from this data that might kind of affect my citizenship?

And so what it does is it kind of gives you a small window into what you might look like as someone who is composed entirely of data. And that you know, maybe allows you to actually think about both the issues involved and about how your own behavior affects that. Like some people have said that using this thing has basically made them try to browse more locally, right. To actually think about that maybe I should just use these web sites kind of within my own country where I know the laws that affect it. Or, maybe it’s a way of proving that you’re actually engaged with other things. I was thinking maybe like with various kind of EU debates—votes, referendums—that this could almost be used to actually prove that you’re an engaged European citizen who isn’t just interested in what goes on in your own country but is involved elsewhere.

I think that’s also a super dangerous idea. Like you know, I realized doing this project that actually a voting system based on surveilling everyone’s activities is a terrible idea. But it’s necessary I think to kind of prototype these things to work out like what might the ramifications of them be. So it’s not just like the spy agencies who are deciding how our data is processed and how our identities are constructed. But actually that we get to be involved in that kind of decisionmaking process as well.

The other thing it does is make this kind of map somewhat visible, right. This thing that we don’t think about too much, which is all of these physical locations of data. The way that these things are housed in very physical locations.

Because as I said, we we tend to have this image of the Internet as a cloud. This is my favorite stock image of that. That you connect to this thing called “The Cloud,” when you go online. And the cloud is some sort of like, magical far-away place that you don’t really have to think about. The magic happens over there. We’re not really connected to it.

Ad that emerges from the way in which engineers think of computing resources. If you’re an engineer and you’re designing a computing network, you may draw a few computers. And then you draw a line, it just goes to this kind of fuzzy thing over here. Which basically says, “Hey, as an engineer I don’t need to think about that over there.” The problem is, it’s not just engineers who’re involved in this stuff, right, it’s all of us. And as citizens, as people who are politically affected by that, not thinking about that thing over there? is a political decision that carries a huge amount of weight. If you don’t know where your data is going, where your identity is being constructed, you’re essentially kind of locked out of political engagement with the processes that result from it.

And so for me, this kind of metaphor of the cloud is this terrible metaphor. Because it kind of keeps people away from thinking about this. And sort of controls our perceptions of the network. And by controlling that perception and understanding of the network, you control people’s perception and understanding of the political processes that are engaged with it. The terms we use for these things, the names we used to describe it, turn out to be incredibly, incredibly important.

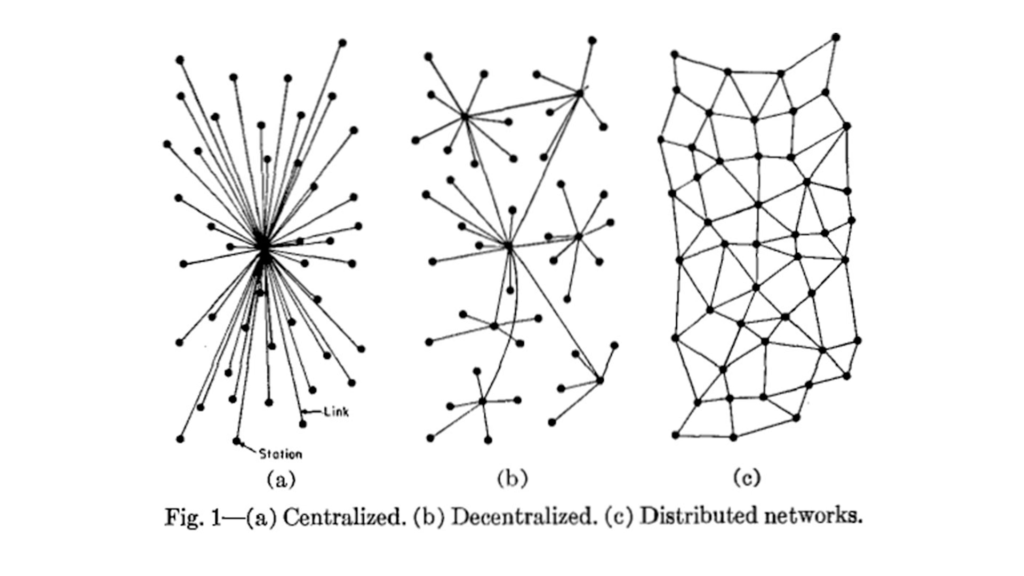

This is a very famous illustration in nerdy networking worlds. It’s from a text called “Distributed Communication Networks,” written by a guy called Paul Baran in 1964. It’s kind of the blueprint for how some ideas of the Internet came to be. Which is that you had this idea of old networks, which were centralized kind of things where everything went into a central point and then got out to the edges again. You had decentralized networks, where there are a few nodes. And then you had this idea of what the perfect distributed network would look like, which is the idea of the Internet. And this is the image that’s often used to kind of show that difference. The Internet is all these things connecting to everything else. And it’s a beautiful image and a beautiful idea.

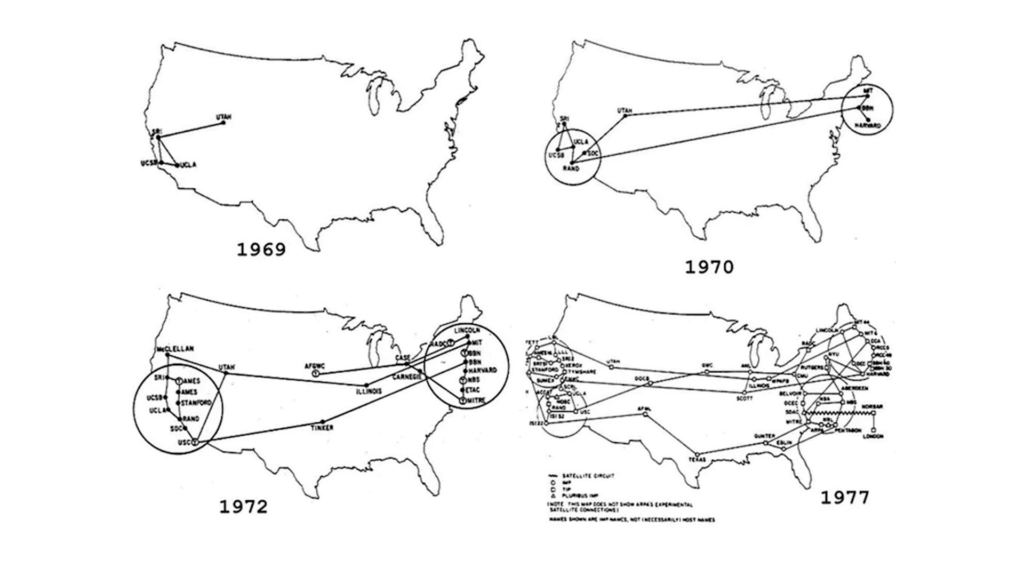

It’s not entirely true. This is a series of diagrams of the growth of the ARPANET, which was the American predecessor to the Internet, which was the very first kind of connections between loads and loads of computers. It’s not terribly decentralized. If you can read it very carefully you’ll see that already in 1977 there’s a node here marked “NSA.” They were plugged into this network on a very very early level. So the connections between supposed decentralization and actual surveillance were kind of built into this network from the very very start. And also they were…they were quite clear, if you paid attention to it. But again, the kind of opacity of these things, right. The fact that people look at this and go, “Ooh, that’s like a weird technical diagram,” means that the understanding of that is regarded as being a technical understanding rather than a political one.

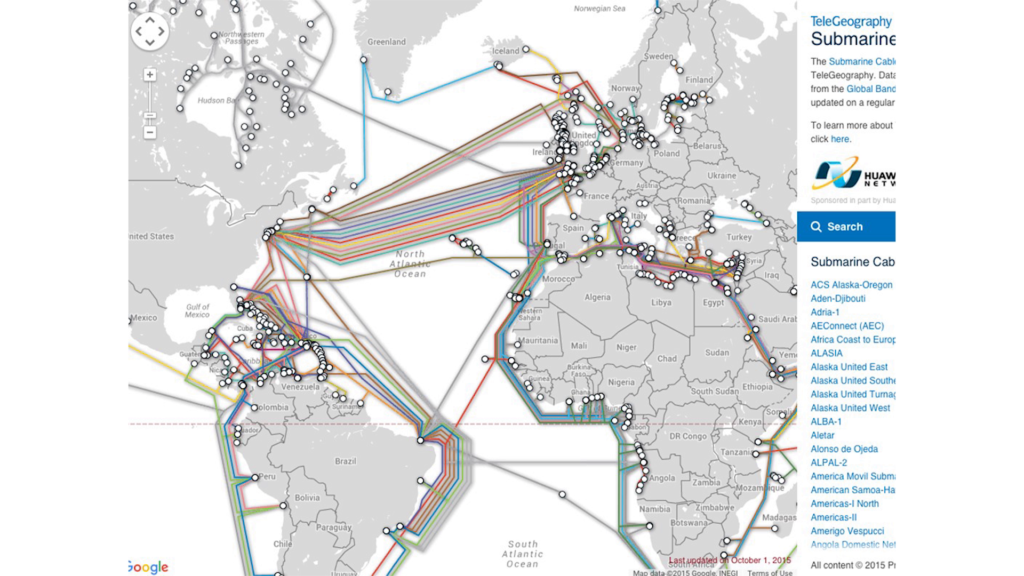

This very much continues into the present day. This is a map of undersea Internet cables. These are the cables that actually transmit the Internet around the world. And there’s quite a lot of them. And they’re mostly owned by large telecommunications companies. But the really interesting thing for me is the way in which these networks are not like some entirely new, egalitarian connection of the world. These are mostly the shipping routes of empires that preceded them. If you have…for example down here in West Africa, you have a bunch of countries that used to be part of the British Empire. And if you’re in those countries and you use the Internet, the cable connects you straight back up to London again. If you’re using the Internet in West Africa, most of your data traffic still goes through London. That’s still its connection, because that’s where the original telegraph lines and old telephone cables went. That’s who owns the route. Similarly if you’re in South America, huge amounts your traffic still passes through Spain to get to anywhere else.

So instead of actually recreating this amazing kind of new utopia of connection, mostly the fundamental architecture of the Internet reproduces these old kind of imperial and colonial routes. And when we think that these empires went away, really they just kind of moved up a level into the infrastructure.

This is starting to permit weird new interesting things happening to identity and citizenship, right. Not just the algorithmic citizenship that I talked about, but a weird process whereby you can start to offer parts of things that we thought that only nations could do. Or that still mostly only nations can do. Like offer you to certify your identity. To offer you here, you can set up a business; here, you can get some kind of identity or document; you can sign contracts, right. These things used to be functions of where you were physically located, because that was your citizenship, right. You live in this country, you get your identity from this government. But this spread of the networks around the world is starting to allow governments to offer this in different ways.

One of the countries that’s doing this quite intensely is Estonia. So if you don’t know, Estonia has spent the last couple of decades rewiring itself as an incredibly digital place. It’s spent huge amounts of money in IT. It has an incredibly successful kind of digital government program. It has basically the best government web sites in the world. Which basically allows them to offer very good services to their citizens. It’s a lot easier, in Estonia, to register with the government, to vote online, to pay your taxes online. Because they just built really good web sites.

And they realized their web sites were so good other people would like to use them as well. So they created this service called e-citizenship, which allows anyone in the world…with some identity checks, and for a small fee, to become an “e-citizen” of Estonia. Which basically means you’ve decided that their government web site is better than your own government web site, and you prefer to use theirs as kind of Government As A Service. As a business proposition.

The thing is it only offers some of what we get as a citizen. This idea that with a passport, you don’t just get an identity. There’s some other stuff that comes with it. For example the right to live in that place. And maybe some kind of healthcare benefits, legal things like this. But e-citizenship is designed to give you a bunch of government services (taxes, contracts, businesses) without residency. Without any of the physical stuff. Just the kind of virtual services. I think of it as a kind of delamination, like a kind of separation, a sliding away of the different things that government is supposed to do, enabled by this digital service.

And that in turn is producing weird geographical effects. This is a data center in Luxembourg. Remember I said with the web sites in Citizen Ex that this data is actually located in particular places? Well, Estonia has a particular problem, which is that they’re very very close to Russia. And it makes them slightly nervous. Not least because one of the problems with digitizing your whole country is if you get invaded, it’s super easy to wipe the hard drives and basically wipe out your country. So what they’re doing is they’re backing up Estonia in other countries. Just as you back up hard drives—as I hope you do—in other places.

So all of the Estonian data is stored, apparently, in this data center in Luxembourg. In which a small area of the data center, like a bunch of actual servers, has been declared sovereign Estonian territory, just like embassies are as well. So you have what they’re calling a kind of virtual embassy, but it’s a very real place. It’s a solid piece of ground that belongs to that country, but it’s for data rather than people.

And all of these different processes for me are kind of ways in which we’re kind of changing this perception of what these citizenship and identities are. Starting to regard them less as being kind of fixed things, geographically-related, but they’re kind of becoming virtual and more kind of cloudy and strange.

And this delamination process as I said, this like splitting apart of what constitutes identity or citizenship, is to me one of the key processes that’s happening around everything being digitized.

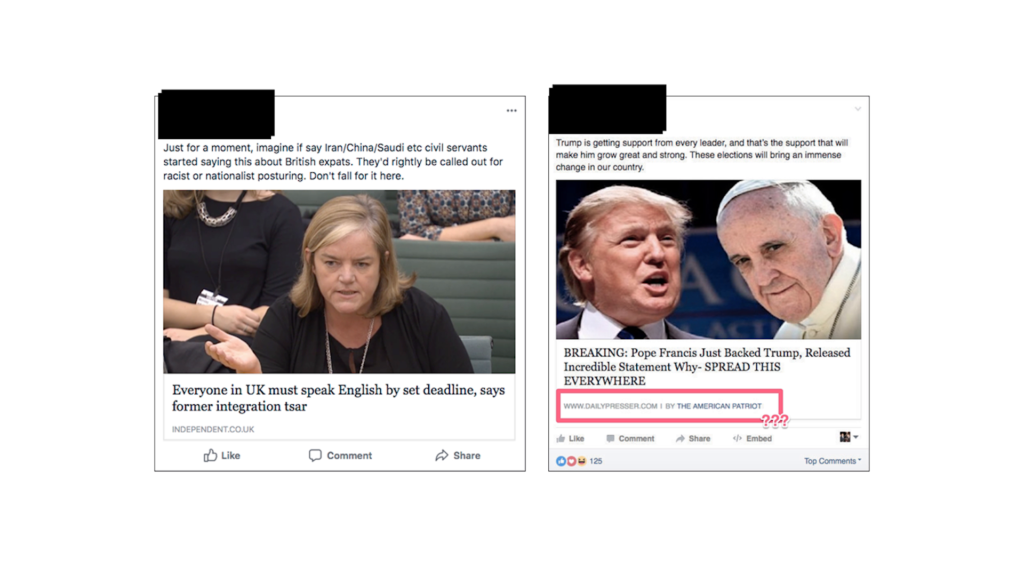

So one of the key ways I see this delamination happening is in news organizations, is in information itself. This is a simple example from Facebook. It’s something I’m sure you’re very familiar with, which is basically two Facebook posts have two new stories, both of them from news sources, except without looking quite carefully it’s quite hard to see which source they come from.

It turns out one comes from a fairly reputable British newspaper, and the other one comes from a web site called The American Patriot, which is set up by some guy in a garage in Utah. And this is the delamination of information. It’s the fact that all information essentially looks the same in a system that’s kind of designed to kind of give you information without any regard to its context or its source, and and this stuff kind of gets muddled up together as they pass through these digital networks.

And there’s a really interesting example of this that happened that got a lot of press around the time of the US elections in 2016, which was I think when the first kind of…everyone became aware of these things…became known as “fake news.” This was not where all the fake news was coming from, but it got a huge amount of press around the election, to the extent where even Obama was publicly complaining about it. Which is that there seemed to be a huge swath of these insane made-up stories, and they were all originating from a specific place, it was claimed. Or a huge number of them were. And this was a town in Macedonia called Veles, which is the second city in Macedonia. This town suddenly produced this kind of boom in fake news, where a bunch of quite young people all figured out they could make large amounts of money by feeding Facebook with incredibly stupid kind of made-up stories in return for advertising money.

And they’d been doing this for a while. It turned there were kids there who we running these health sites. They were running these kind of weird advertising networks. There was just a bunch of kids who kind of figured this thing out. And they were quite successful at it. As in they made a reasonable interesting amount of money. I think the claims to which they influenced the election are probably massively overblown, and most academic research seems to support that. But it was very strange, the sudden realization that a bunch of kids in the Balkans could supposedly have this influence on elections, or that they’d figured out this property of networks that allowed them to feed these fake news stories in return for money.

And there was a huge amount of journalistic interest in this. A lot of the press in the US was super vindictive, was really quite aggressive, was calling these kids all kinds of terrible things and saying they’re irresponsible and stupid and blah blah blah, and they’re messing with democracy.

And the thing that struck me most about it was actually how…perhaps unsurprisingly, how little they understood the context in which this was occurring. Which is the context of kind of recent Macedonian history of the last twenty years. Which is itself a debate around kind of names and identity and citizenship, in a really key and important way.

For those who don’t know, Macedonia has been locked in a naming dispute with Greece for the last kind of twenty-five years now, where Greece doesn’t want the country to be called Macedonia because that’s the name of a large Greek province. And as a result have kind of continually blocked Macedonia’s applications to the EU and NATO and so on and so forth.

And as a result, one of the things that’s happened in Macedonia is the government has moved increasingly to the right. And they’ve kind of doubled down on this creation of identity by doing things like erecting kind of massive statues in the state of Skopje to what’s officially called “The Horseman,” but everyone knows is Alexander the Great, who is a figure from Greek Hellenic history, from Greek Macedonia, but has been kind of willfully taken up to create a kind of new national narrative in Macedonia.

And for me what this says is that this isn’t a problem created by digital tools, right. It’s not Facebook or advertising turning up and creating this. This is a problem of kind of ongoing questions of national identity, of creating kind of national myths that bleed through into these weird questions of kind of individual identity.

It’s worth noting that just in the last month or so, in trying to defuse this they’ve actually taken down… This is the statue not from the center of the town, but they had another Alexander the Great in the airport, which has been removed. And it’s now apparently sitting in a warehouse somewhere in Skopje, and they don’t know what to do with it. Which made me think of one of my favorite artworks in the world.

This is a piece by an artist called Dan Vō, it’s called “We the People,” where he made an entire recreation of the Statue of Liberty, panel by panel from the original plans, which is exhibited in pieces all over the world. Like he shipped it to different locations, so you only get to see little bits of it all over the place. And I was wondering if maybe this kind of Skopje horse could be distributed all around the world to some kind of interesting effect.

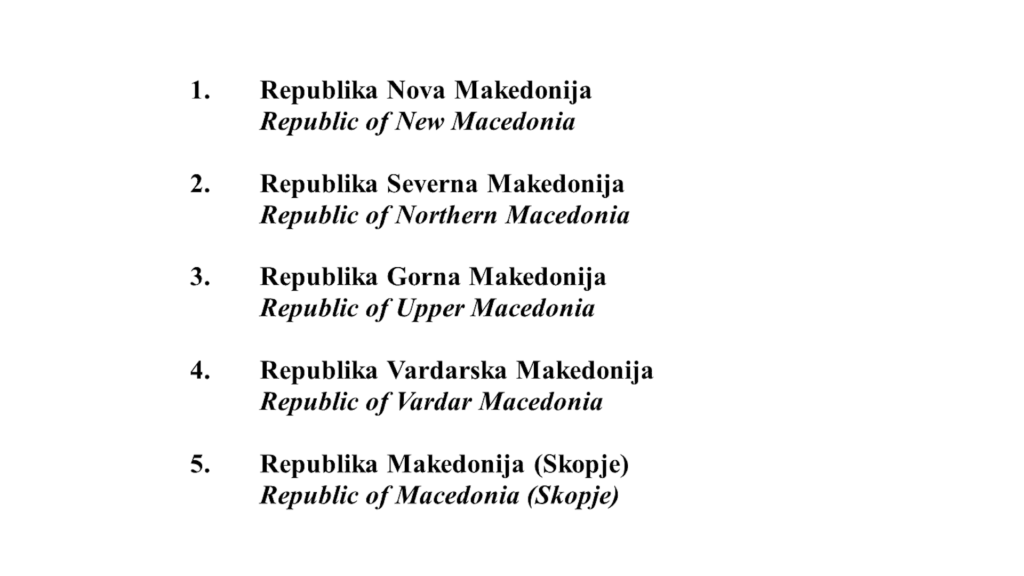

But there’s this joke amongst computer scientists that the hardest thing in computer science is naming things, right. When you build these incredibly complex structures, computational structures, you have to name stuff. And the names that you give the things end up deciding how they get used. And so these are the five names that are currently on the table between Macedonia and Greece for a possible resolution of this naming dispute. Greece are adamant that they can’t be called Macedonia but they’ve put forward these other options.

And I find them kind of fascinating, in the way in which they roam around different qualifiers, right. They all still include “Macedonia” but like, there’s temporal ones like New Macedonia, or Vardar Macedonia, which is one of the old names for the area. And there’s also geographical ones, like Northern and Upper Macedonia. Like, which of these makes this name okay to use? How do we decide if it’s a question of new time, or a question of kind of redrawing borders, redrawing the geographies to make it work?

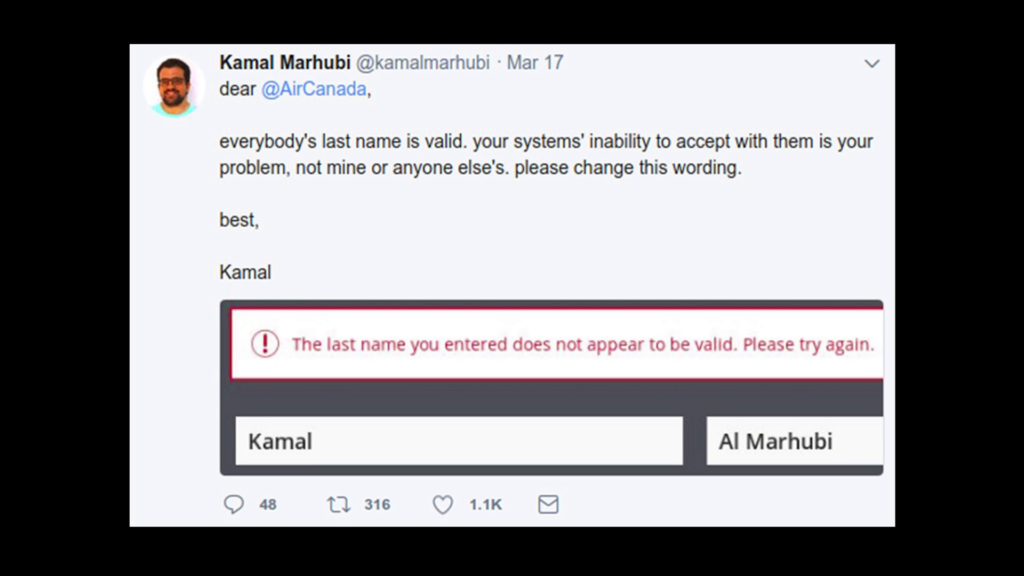

This collision of names and technology is a pattern that we keep seeing kind of returning over and over again. This was a recent tweet that I came across. Someone complaining that in this case Air Canada’s checkin system wouldn’t accept their name as valid. I think because it had a space in it, which seems like a really simple kind of thing to fix, but actually a thing that people all over the world face all the time. That their very identity that they go with in one part of the world doesn’t fit into the systems created somewhere else.

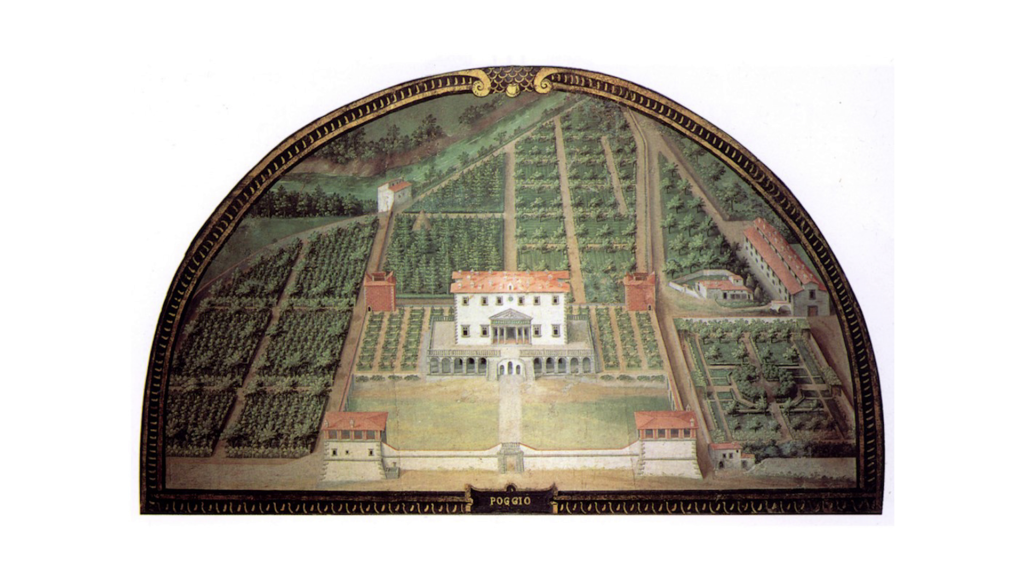

And in fact the control over people’s names in this way is a super old social and technological problem. One of my favorite writers, a guy called James C. Scott uses naming as the kind of basis for his understanding of how political systems as a whole work. One of his examples is about the way in which the government of Florence in the 14th and 15th centuries created a state, as it was then in Italy, by insisting that people got names, right. So in the 14th and 15th century, most people didn’t have surnames. They just had their first name. They were John from somewhere, or Giorgio from somewhere else, right. And everyone knew them as that and there could be many of those people in the same town.

Which is fine if you know everyone. But really really difficult if you’re trying to compile the tax records for a whole region, right. And so the government insisted that they would have to take on those names. And it took almost 200 years for the government of Florence at the time to assign everyone a name. And in their telling of it, in the kind of official telling of it, that’s because that was a kind of education problem, right. That these people were kind of stupid peasants, they didn’t understand that they needed to to have proper names, and that it was good for them to be able to access goods and services and government provisions and so and [indistinct] like this.

But there’s plenty of evidence that this wasn’t really how it worked. There’s plenty of evidence that people were pretty aware of exactly why the government wanted to name them. And that by having this “proper” name, they would be subject to kind of various forms of tax and possibly down the line kind of censorship and oppression. And so they very much actively resisted being kind of given this name from the outside. And it’s only with the fact that the government eventually actually was capable of offering them real benefits. Like oh, if I have a name I can vote. Oh I see, that’s something that I can actually use. Then that’s a kind of reasons take on a name, right.

So every time this naming process happens it’s this kind of bargain. It’s like okay, you want me to take a name so that you can tax me or whatever. But in return, I need to have some kind of access to governance. I need to be able to use that name for my own benefit.

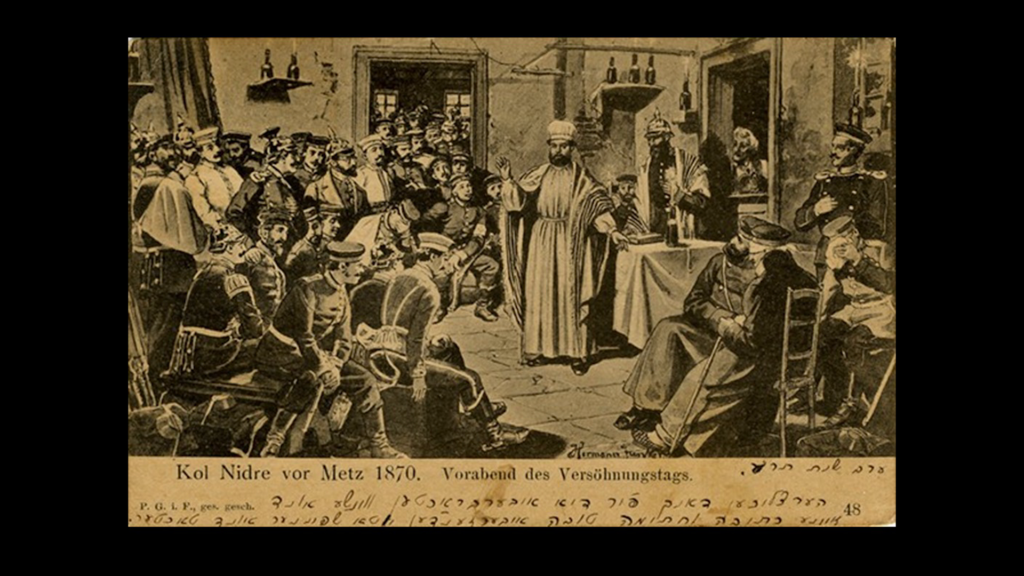

And this stuff throughout history has always has always been deeply fraught. In the 18th century the Prussian government, of Prussia within Germany, went through a similar process of insisting that its Jewish populations all received state-sanctioned names. And they gave them very specific lists of names they could choose from. And everyone in the community had to take one of those names. And the argument was made…possibly in good faith but mmm, unlikely, that this allowed them to be given the benefits of citizenship: the ability to vote, possibly kind of healthcare-y type things, as much as you got that in the 18th century, right. And all these citizens were named.

The result of that of course was that 100 years later, they had lists of the names of all the Jews. And anyone with a name from this particular list was immediately identifiable as someone of Jewish origin. And that naming made it incredibly easier for an entirely different government to then oppress and [indistinct] those people.

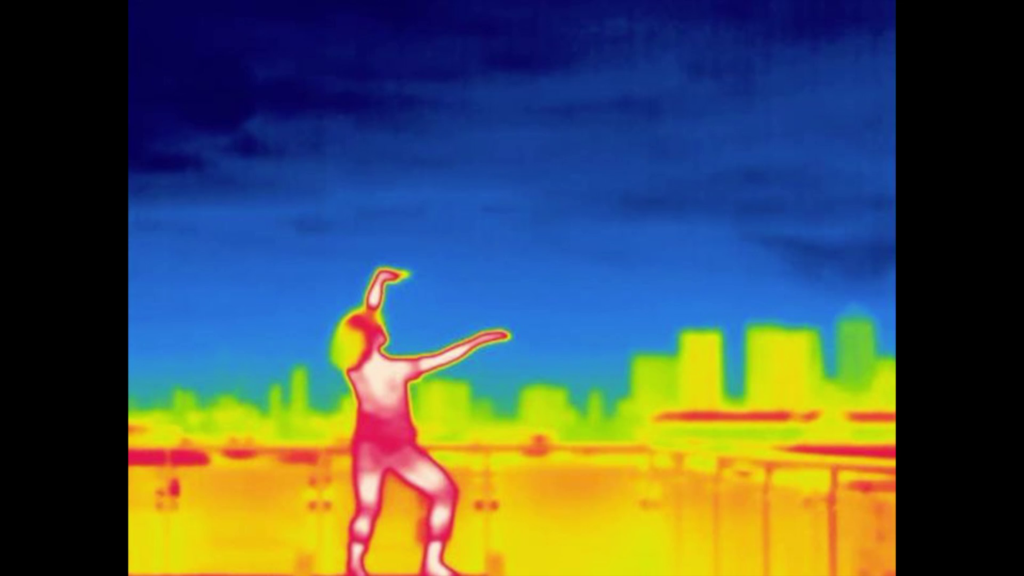

This is right there in one of the works in the exhibition. This is the film that you watched before, which is called We Help Each Other Grow, by an artist collective called They Are Here. It’s in the exhibition. You can see it again. The dancer in this film, Thiru Seelan, is Tamil. And in Tamil naming conventions, a person has a single name, which is just their surname prefixed by their father’s initial. So I would be J. James, because I’m James and my father’s John, and that would be my whole name.

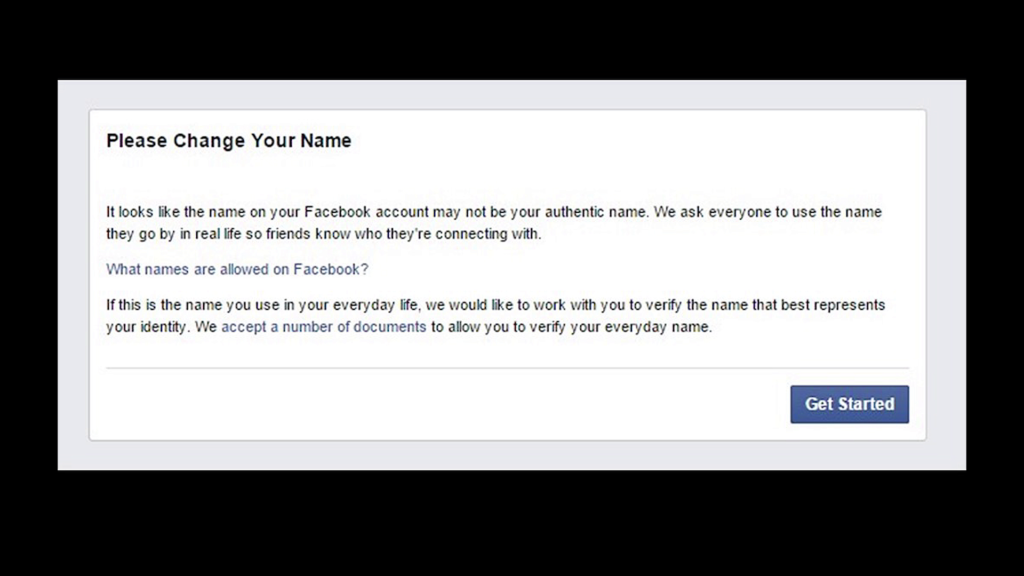

Tamil people have had huge amounts of problems signing up to Facebook. Because Facebook insist that you have a proper name, just like that guy had problems with Air Canada. They need you to have a proper name that they can identify with. Loads of Tamil people have the same name and Facebook has continually rejected their names because like, it doesn’t enable them to differentiate between them. So loads of Tamil people basically make up names for themselves so that they can access Facebook.

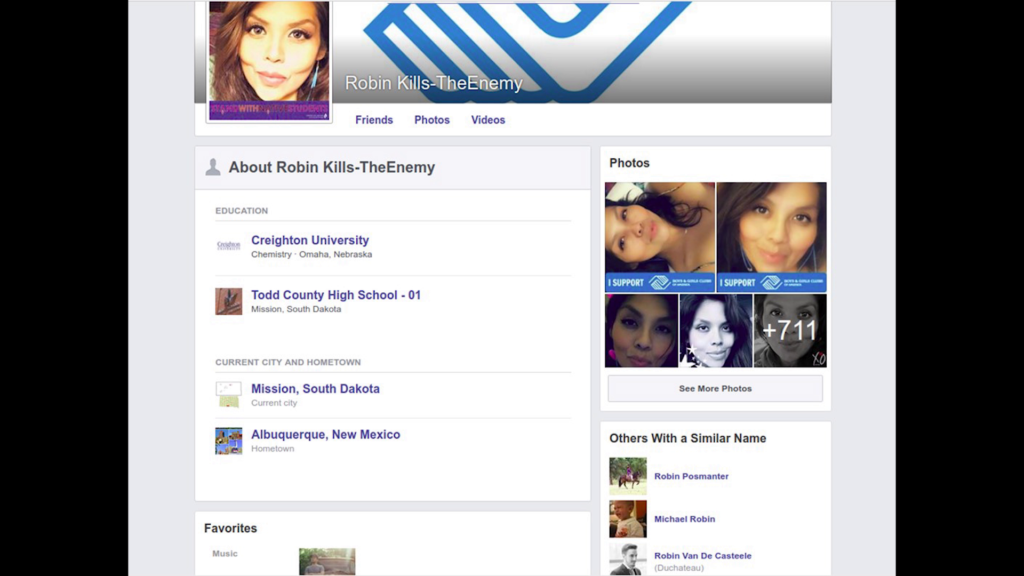

Other people have huge amounts of problems with the same issue with names. This is the brilliantly-named Robin Kills-TheEnemy, which is this person’s real name. They come from an indigenous heritage and this is the name they were given. But they were banned from Facebook for a year and had to appeal and go through a whole bunch of legal stuff and complain, and get press about this in order that Facebook would admit that this was a kind of possible name for someone to have.

The reason of this problem is that Facebook has this thing called a real name policy, which is exactly the same as the Florentine issue of the 15th century where they wanted a name that made everyone kind of singularly identifiable. Not in this case so they could tax them but so they can suck in all their data and use it and sell it for profit.

They also make the claim, which I think is super interesting, that anonymity is a problem in communities. This remains, it seems, a really fraught, academic debate. I’ve read papers on the one side that say anonymity basically allows people to behave incredibly badly. And obviously we’ve seen this on most social networks, with kind of anonymous trolling and really horrific behavior.

There’s also a whole bunch of academic research that says that anonymity’s actually really good in groups. Because if that’s reasonably controlled, people have to behave well because they don’t have any other identity to fall back on, right. If you behave badly as an anonymous person, if that group is democratic then maybe you’ll be kicked out of that group and you won’t be able to behave in it. So actually in certain situations anonymity allows people to behave better, because their identity isn’t tied to other identities that they have. There’s nothing else to fall back on. So at the moment we’re sort of unclear on where that falls.

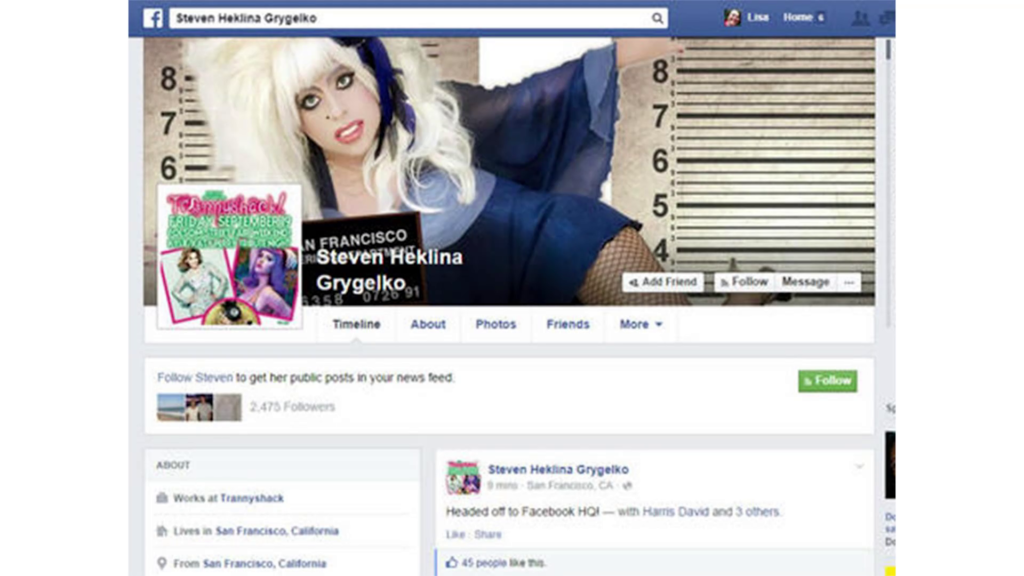

But right now it’s a thing that super impacts specific communities more than others. Non-English communities with different naming conventions, like the Tamil one. Or people that want to choose their own identity. This is a drag queen called Heklina Grygelko, who who was forced to insert the much-worse name “Steven” in front of their Facebook identity because that was the name that matched their ID. This is the “real name” policy. And Facebook’s thing is like, “No, we are the authority for deciding what one’s real name is.” And this always impacts communities—in this case LGBT communities—who have had the Internet as a kind of safe space. But as soon as you import these ideas of kind of tractable identity, that starts to fall apart.

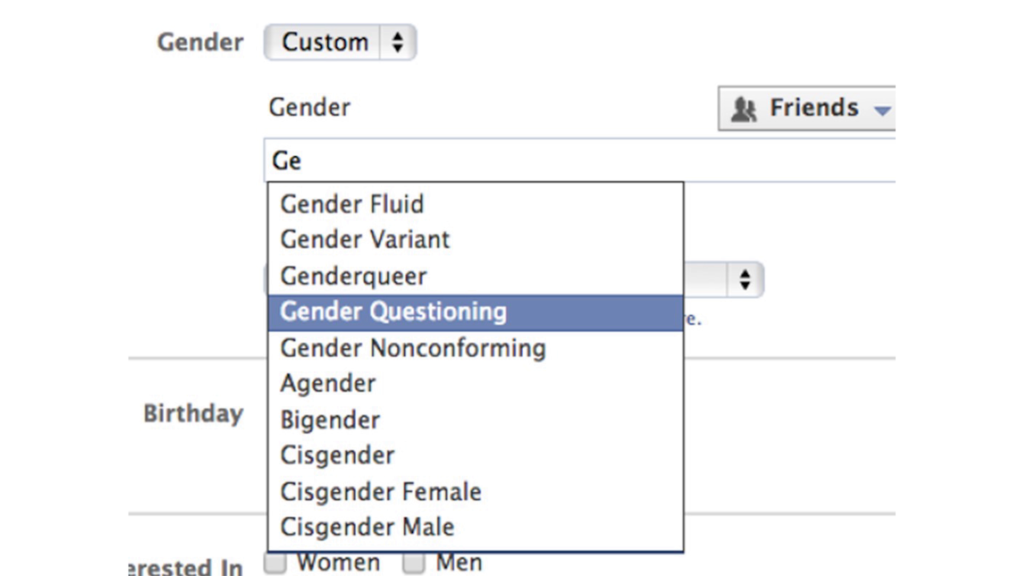

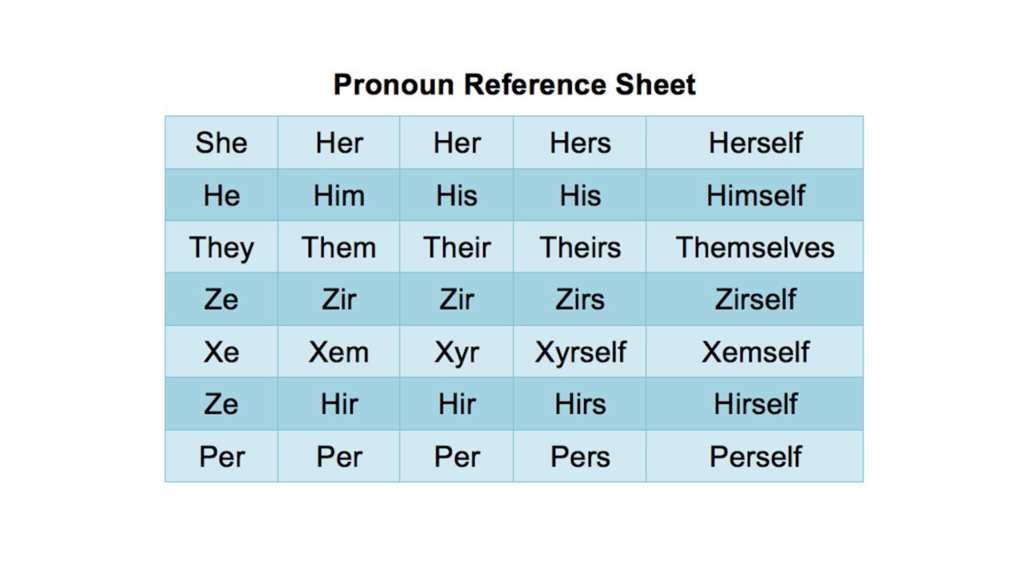

A couple of years ago, Facebook did try and make some efforts towards better identity stuff. And this was one of them, which is where they instead of saying that you had to register yourself as male or female, they introduced about seventy different variants upon this. And you know, people could actually—you can change this now. You actually have a kind of flexible identity with this system.

And I don’t want to use this to suggest that Facebook is like, good—or very good at this, even—but rather that technology, sometimes, actually makes visible these forms of identity in ways that didn’t have this visibility before. So all of these identities, or these potential identities, have always existed, right. But we didn’t necessarily have a kind of common awareness of them that allowed them to actually start to affect society more widely. And this is in part where the “trans” in “Transnationalisms” comes from. It’s this belief that despite many of the horrors and the damage of this kind of attempt to squash people’s identities into little boxes, the pressure that that creates on those boxes actually starts to reveal a whole bunch about human behavior that may’ve been kind of hidden before. And that given enough charge starts to create some kind of critical mass, right, that makes it at least undeniable. It may at times increase the possibilities for oppression, but it means that those things can no longer remain kind of completely hidden and unrecognized within society.

The fight that’s happening now in a lot of the world over pronouns is super interesting to this. Because it’s this fight right to the level of languages. And there’ve been these different proposals around for a while of how we can de-gender pronouns. So instead of having him and her, he and she, in a variety of languages, you can have these different things. In English we seem to be gravitating towards using “they,” the singular they, as something that’s neither male or female.

Lots of people seem to be really pissed off about that, and they’re idiots. Americans in particular think that like, they is plural but singular they has been around for ages. I was in Sweden recently, where they’re super right-on. And they have a gender-neutral pronoun already, which is “hen” and everyone’s using it for everything, because they’re Swedish. In Finnish there’s already…the pronouns don’t have gender, which is great. As I am understanding it, in Slavic languages it’s more complicated than that, where “they” is already masculinized in some languages and there’s no obvious alternative.

But the thing is that language is a technology. It’s a tool. Like any other one, over which we have this kind of power to construct through this kind of code as language. We have the power and agency to kind of reshape the way in which we understand the world by reconfiguring this code in which we describe stuff.

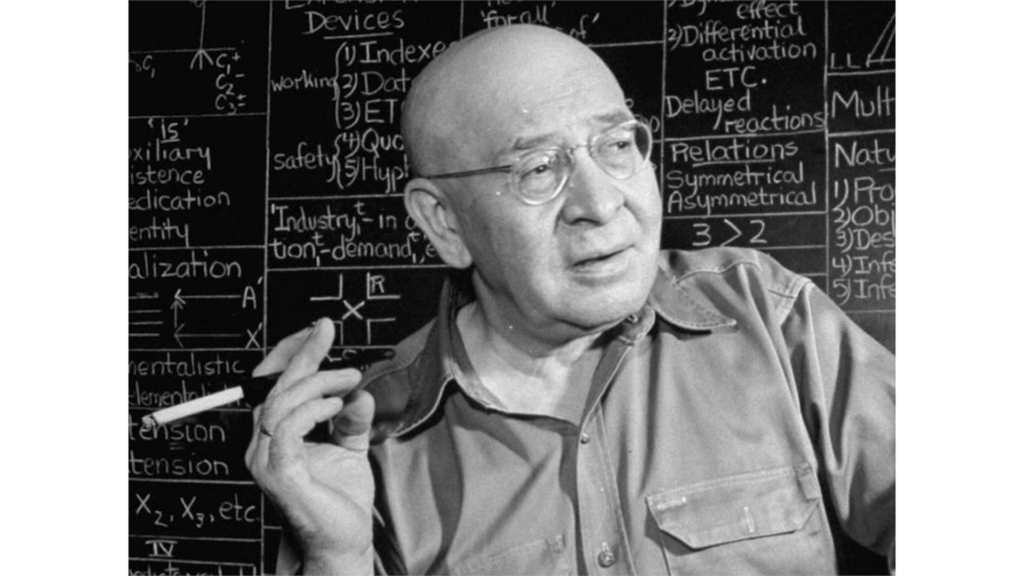

The guy that that always makes me think about is…the way in which we can make these kind of cognitive and social changes through language. This is Alfred Korzybski, who is a semanticist, whose work developed a thing that I’ve always been really fascinated about called E-Prime, which is a kind of psychological way of speaking. And E-Prime does away with the verb “to be.” In E-Prime—English Prime—you’re not allowed to use the word “to be.” And it actually makes language both more precise and more psychologically healthy.

So instead of saying, “I am depressed,” you say. “I feel depressed.” And immediately you have this difference between a thing being what I am and being a kind of temporary state, a thing that actually is susceptible to change. And I have this weird sense that maybe like, insisting on things like gender-neutral pronouns is like Korzybski’s E-Prime, this way of kind of deliberately restructuring language so that we see the world in a different way.

This is a hilarious slide I found in a quote web site but I couldn’t resist it. This is the most famous quote from Korzybski, which is that the map is not the territory. The [word] is not the thing it describes. That language is not the way that the world is. The world is the way it is and we have these bad maps for navigating it. And all these things I’ve been talking about, these constructions of citizenship, these constructions of identity, these constructions of language, are metaphors. Just as “the cloud” was a bad metaphor for how we think about technology, most of the linguistics stuff that we use is a bad metaphor for actually how we describe stuff around us.

And the things that we’re building, like Facebook, like other technological systems, they shape the social reality. But what it confirms is that in the engineering, in the social sciences, in the linguistics, they’re not abstract concepts anymore. The power of these technologies can actually kind of start to intercede in the world. It’s right there in the lines of code, or in these fiber-optic cables running under the oceans, the web sites we use every day. It makes these things really clear and visible to us, that these are the processes that work in the world. Things that used to be cloudy and hidden and uncertain. The rules of power, the rules of politics, are increasingly written down in these systems which we can access.

So to finish, what I said about the cloud earlier as something that’s often used to kind of obscure our understanding of the world and needs to be kind of picked apart and like, mapped out in all these different ways. It’s worth remembering that the cloud is also the cloud because it’s complex, right. The cloud is cloudy. It’s super hard to understand. It actually—I kind of start to think that maybe it’s a really good reflection of reality, a reality that is complex. That’s capable of containing all of these different realities, these different identities, that are and always kind of remain subject to change. Just as we’re capable of redrawing maps to redraw the state of our nations and the state of our citizenships, we’re capable of redrawing these tools and these systems, and even language itself, to kind of present ourselves and the world around us differently every day. That they remain constantly kind of open to question and open to change. Thank you very much.

Further Reference

Transnationalisms: Borders, Bodies, and Technology event page