Hi, my name is Kyle Machulis and this is some words about some sounds about Pier 9.

To start, let me introduce who I am by way of what I do. I have worked in the past as a robotics engineer, both on small-scale educational robotics (So if you’ve heard of the Handy Board, or the Xport Botball Controller, or the Interactive C language, I worked on those.) and I also worked on space platform work. So this was a rover that went to a very lunar part of California, or a Mars drill that went to a very Mars‑y part of Spain. I also worked on self-driving cars and large-scale mobile mapping. In between stints as a robotics engineer, I worked as an engineer on Second Life for Linden Lab. These days I’m actually working on web browsers (because those involve a lot of robots?) for Mozilla. I’ve worked on their Firefox OS phone and on hardware-based initiatives to bring hardware to the web.

In my spare time, this is what I do. This being reverse-engineering. Basically, I find hardware that already exists, because I’m really lazy and making hardware is really hard. So I find something that already exists, already shipped, but it does something that I want it to but it doesn’t do that yet, or it does something that someone else wants it to but it doesn’t do that yet. Like the drivers don’t support it, the firmware doesn’t support it. I make the driver support it, or I make the firmware support it.

Probably the most well-known project I’ve been a part of was reverse-engineering the Microsoft Kinect. I was part of the team that wrote the open-source drivers for the Microsoft Kinect so that anyone could use it for damn near anything, as you’ve probably seen in many Instructibles, art projects, research projects, whatever.

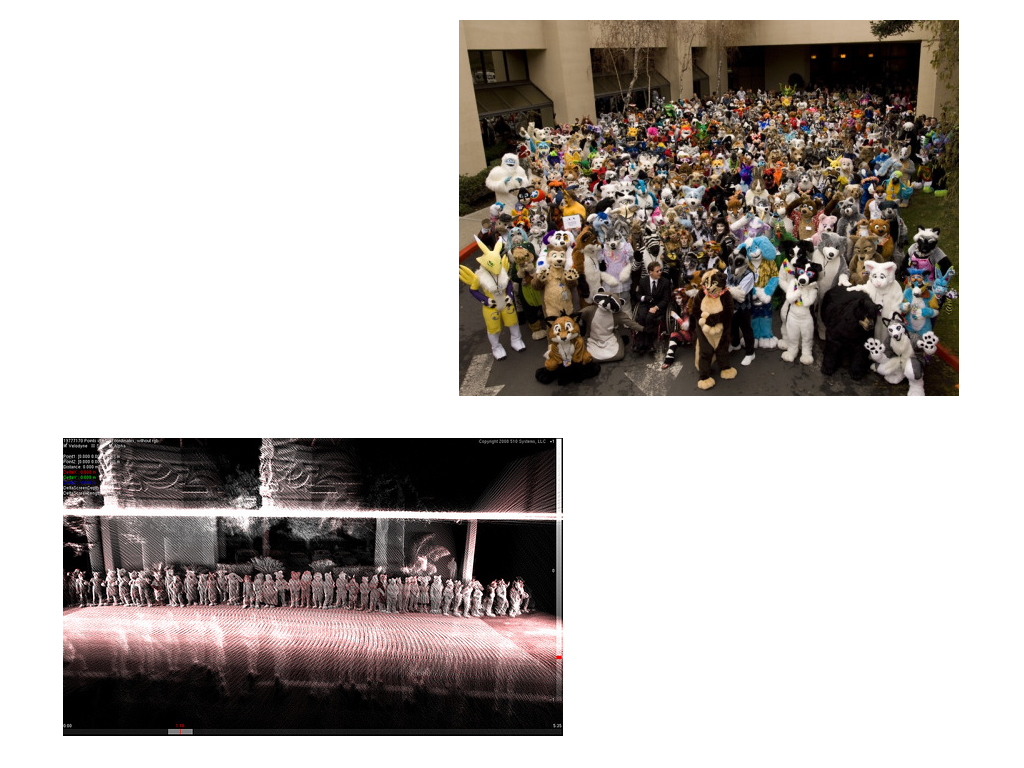

In terms of how this comes into creativity, though, why am I here as an artist in residence? That’s kind of a good question and I’m still pondering that, too. But I really like to take very expensive hardware that I’ve reverse-engineered and do really stupid stuff with it. So for instance I took all of our scanning hardware and sensors that would make a car drive itself, and took them to a furry con and made a gigantic point cloud of 512 fursuiters. It’s all available online, open source data.

I’ve also done things like hooking up exercise equipment to Second Life, so you could ride your exercise equipment and it would drive your virtual car. Or reverse-engineered the My Keepon bot so that when you were dancing in front of your Kinect it would actually dance with you, it would dance like you.

Then there’s what I’m really known for, though. The problem with this (and by the laughter you can tell who knows what this is already) the problem with this topic is I’m kind of at a workplace right now. And there’s a reason that the term Not Safe For Work exists. I tried to find a good picture of one of the projects that I do in this realm, couldn’t really find anything that would fit in this environment, tried to mosaic some of the stuff and it still was just a little bit too graphic? So what I did was I just averaged all of the colors in the picture. This is possibly the most NSFW color you’ll ever see:

So, combining all of these things, we come to my artist statement:

This was the approach that I took when coming to Pier 9. I originally visted Pier 9 just to come and say hi to Paolo, but as I was here I saw other artists like Ben Cowden and other people that I knew in the workshop and they’re like, “Hey Kyle, you should come be an artist in residence.” And I was like, “Okay.” So they introduced me to Vanessa and Noah, and they were like you should come be an artists in residence, and so I’m like, “Okay. I guess I do art now.”

The problem is I have to combine all of this, the thing that I do, with this gigantic workshop with all these machines in it. And I had some ideas but the thing is then you talk to Vanessa and Noah and you look at the workshop and they’re like, “Feature the workshop.” And it’s like but wait, I don’t know how to use any of this stuff yet. I’m mostly a software and embedded engineer, so if I was going to feature the workshop for stuff that I knew how to do, my ass would be in there all day. I already do that at home, all the time. I have a very comfy chair. This is what my home lab looks like. It looks basically like the one up there. I wasn’t really coming here to do that. Not to mention there are other ways that I could apply my expertise to the workshop, but then people were like, “No! You don’t put body parts in the water jet.” So that just went right out the window.

So I spent a lot of time thinking “What the hell am I going to do?” How am I going to take the workshop and kind of make it my own, figure out how my practice works in here, and then also feature the workshop on top of all of that stuff. There was a lot of crying, and a lot of panic. I ended up just kinda taking classes, walking around the workshop looking at things. One of the things that I noticed the most was Iris Gottlieb’s drawings of the workshop. The thing that I loved about that is that it recontextualized the workshop in her eyes, and in her aesthetic. So instead of just being this place of tools and prototyping and things like that, it was still a place of tools and prototyping and things like that because they worked really hard on making it that, but it came through her eyes. One of the wonderful things about reverse-engineering is it’s basically applying what you want on top of hardware. It’s recontextualizing hardware. So by taking that approach, it’s like okay that’s really cool. Maybe I can kind of take the workshop and do a thing that’s more me with it, instead of trying to throw myself at it and come up with something.

So through those many walks through the workshop, I kept noticing this sign. It was like, wait a second. If I need to learn all of these machines, and all of them edit materials or change materials or make materials or subtract materials or whatever, every time you do something like that, it makes a sound. And the really wonderful part is whenever you fuck up it makes a really big sound. So you have a fail-safe of output when you use sound, because I could go and try to make a chair and the chair could fall apart and…that’s probably what would happen. But the sounds that came from making that chair, that process, that’s really intrinsic to the workshop. So with that, I was like wait there it is. That’s what I can do.

Shit.

Awesome.

So I decided to go ahead and apply sound to the workshop. What kind of sounds can the workshop make? What kind of sounds can the workshop edit? I could just run around and record everything, but it felt like it needed some sort of direction, even though this place is made to make sure that any direction you have will change five seconds later.

So I came up with a project called Industrial ASMR. Who’s familiar with ASMR? That’s kind of what I figured. ASMR is Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response. Now everyone gets it, right? ASMR is actually kind of hard to explain. There’s a really wonderful This American Life episode on it. Whenever you hear a certain sound, sometimes you get this tingly feeling. It’s not quite goosebumps, it’s more in your head, kind of the back of the neck region, though different people feel it different ways. And it’s repeatable, so every time you hear that sound that thing happens. That is ASMR. The reason there’s a picture of Bob Ross here is because Bob Ross is actually cited as the most ASMR‑y person. Most people say “Bob Ross is the person that gives me that feeling.” And the aesthetic of Bob Ross has come through in the ASMR community. In the videos, you get a lot of quiet speaking, quiet sounds, things like that. I have a demo video here of what ASMR looks like from a YouTuber known as GentleWhispering. These videos have millions of views. This community is huge.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RVpfHgC3ye0

A lot of people are like, “That’s kind of creepy.” But there are some of these videos that are four or five hours long of just all sorts of very minute, very quiet sounds, presented in this way. But you find that one you like and you will find other videos of it, let me guarantee you. Because the response is so interesting. It’s almost a haptic response to sound. It has a bit of a synaesthesia feel to it. It’s definitely something you want to go out and find more of, which is why this community has gotten so big. I definitely recommend going to YouTube, search “ASMR.” It’s blown up; there’s like, apocalyptic ASMR now, because someone likes zombies this way. I don’t even know.

But ASMR is not really my aesthetic. So in talking about the industrial portion of ASMR, I’m a huge fan of industrial music. The wonderful thing about being in an industrial workshop is it’s very easy to make industrial music. But the type of industrial music I’m talking about here is very specific, sort of second-wave industrial, so Einstürzende Neubauten, very early KMFDM, things like that. For those of you that are more used to the 90s synth stuff, this is what the industrial that I listen to sounds like:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=7IL__IAyBuE#t=110

God, it’s wonderful. I love Blixa Bargeld way too much.

So obviously you can see the correlation between ASMR and this, correct?

My goal was to take the sounds of workshop and not just throw a mic in there and record what’s happening, but put mics in really weird places you’re really not supposed to, and figure out what sounds can I extract from these machines. And also make things on these machines and see what happens in the process of making these things. So the thing is you make something on the Bridgeport, for instance, and if you’re taking off too much material it’s a very certain sound. If you’re doing just enough material, it’s a very certain sound. If you’re working on one of the CNCs and you really break something, you get a very certain sound from both the machine and the shop staff running at you screaming. It’s amazing. You can get a choir with it.

So what can I do in this workshop to cause that kind of ASMR response? It’s not something that you can really aim for, because you never really know what kind of sound is going to cause what reaction in someone. But the fun part is trying to come up with as many sounds as possible.

So the equipment that I did this with. This is a very nice recording system called a Sound Devices 722, and around it are non-acoustic microphones. You’re probably used to seeing microphones like this where there’s the big ball on the end of it and it picks up sounds coming through the air. The thing about non-acoustic microphones is that they’re aren’t picking up sound coming through the air, they’re picking up vibrations, or in the case of the little thing that says “Radio Shack,” it’s actually picking up electrical fields. So I’m not just recording exactly what you hear in the workshop, I’m recording things that are far outside of the human acoustic pickup range, or things that aren’t even acoustic in the first place.

Of course, I did use acoustic microphones in places, to pick up motors and things like that, but it turns out that the people that designed this workshop put absolutely no thought into the fact that maybe I would need a little quiet. So acoustic microphones did not actually work too well here, because you pick up a lot of shop noise and things like that. You really actually have to get into the machine and mine for the noise, mine for the sound. Find where you can put a mic where you’re going to pick up one certain thing instead of just the whole din of the workshop, and that was what I did.

The thing with these sounds is they’re not going to be specifically harmonious, or melodic, or things like that. You have to think about what is the texture of the sound, what we call the timbre, the quality of the sound. Usually when you explain timbre, it’s something like what’s the difference between the sound of a violin and the sound of a French horn. They can both play the same note, but you will be able to identify the two of them, and the difference between those two, that is the timbre.

You have to think about that kind of listening when you’re listening to these sounds. I will say these are best listened to on headphones. All these sounds are on my SoundCloud account, and I also have many many hours of recordings that I’ll be posting on the Internet Archive soon. All of the sound data that I took from this residency will be open-source so anyone can do whatever they want with it.

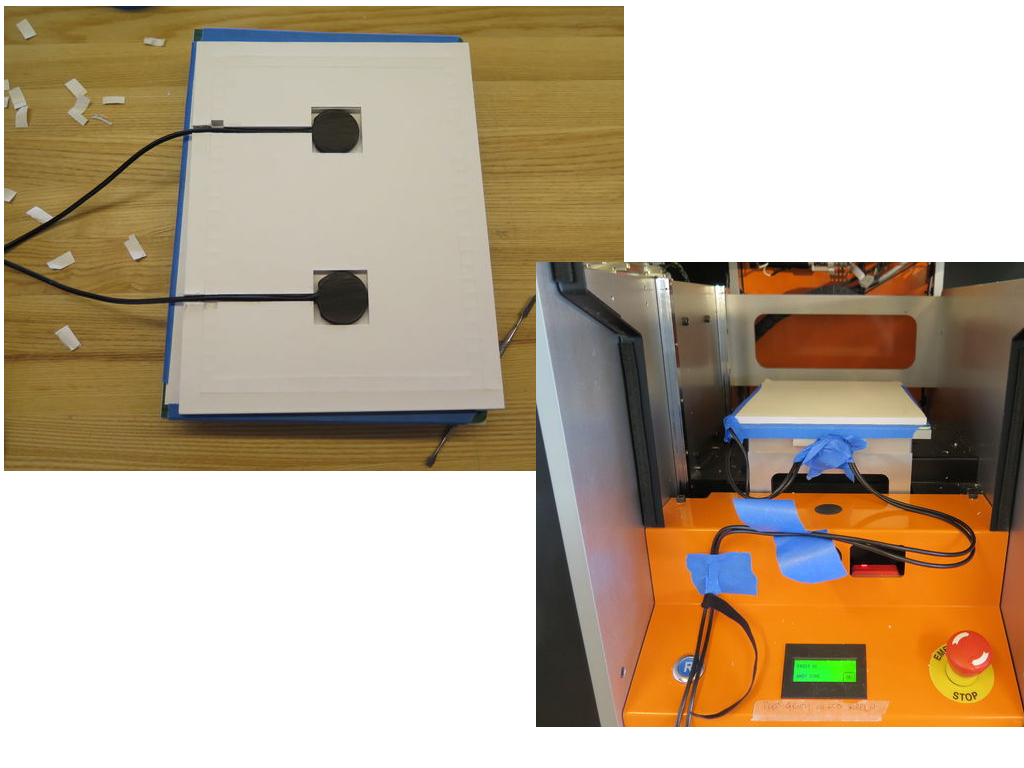

Going into some of the machines that I worked on. The MCOR was really interesting because I actually had to create the platform to put the microphones in. As I was doing this project, one of the things I ended up wanting to do was taking the experience of the material as it was in the machine. With the MCOR, for instance, it’s how can I get the experience of paper as it’s in the MCOR? Can I actually get the sound of the glue wheel running, the knife running, things like that. Here’s what it ended up sounding like:

That is the sound of the paper actually being cut, and you can kind of hear the motor in the background. The way that that platform is set up, the mics are set to right and left channels so if you listen to it on headphones, it sounds like your head is directly in the middle of the paper, what’s known as binaural recording.

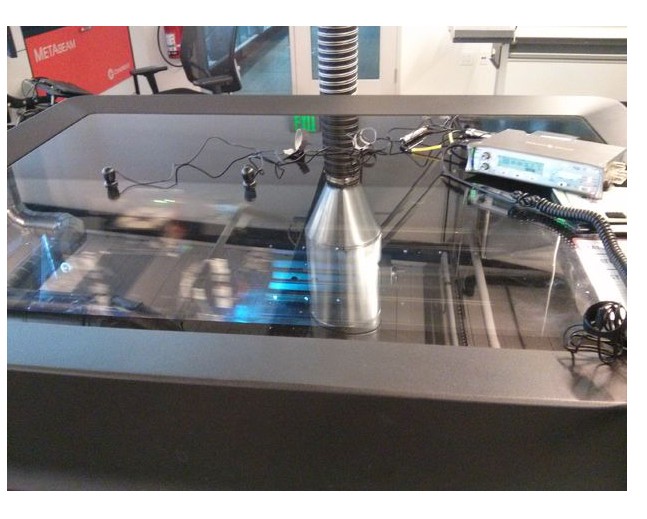

The next sample that I have here is from the Objet. The Objets were super interesting because there’s a lot of complexity in the print head. Using the induction coil mics, which pick up electrical fields, you pick up all sorts of really amazing sounds from the motors and the fans:

That’s from having the two induction coil mics set apart, mixing the sounds to either channel, and you can hear the print head going back and forth between them. That is nothing but the motors and the fans and the print head. But everyone’s like, “Oh hey it sounds like the 3D printer is singing.” It really anthropomorphized the 3D printer for quite a few people that I talked to.

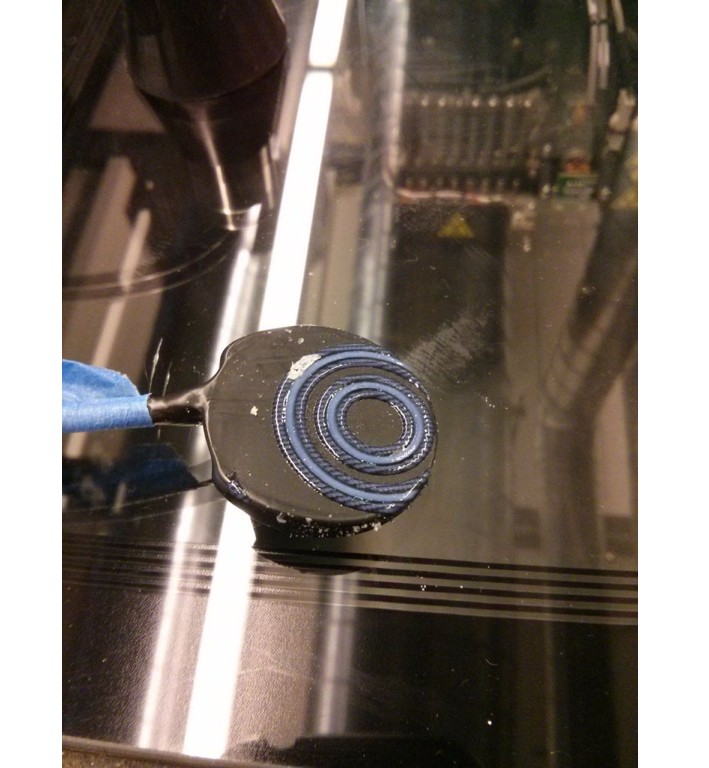

Then, because can’t just stop there, we decided to 3D print on a mic to see if we could get the sound of a print being made:

So being 3D printed on sounds like having a slightly asthmatic person breathing in your ear. Combined with the singing, it makes it sound like you’re being sung to by a slightly asthmatic fairy right in your ear, or something like that.

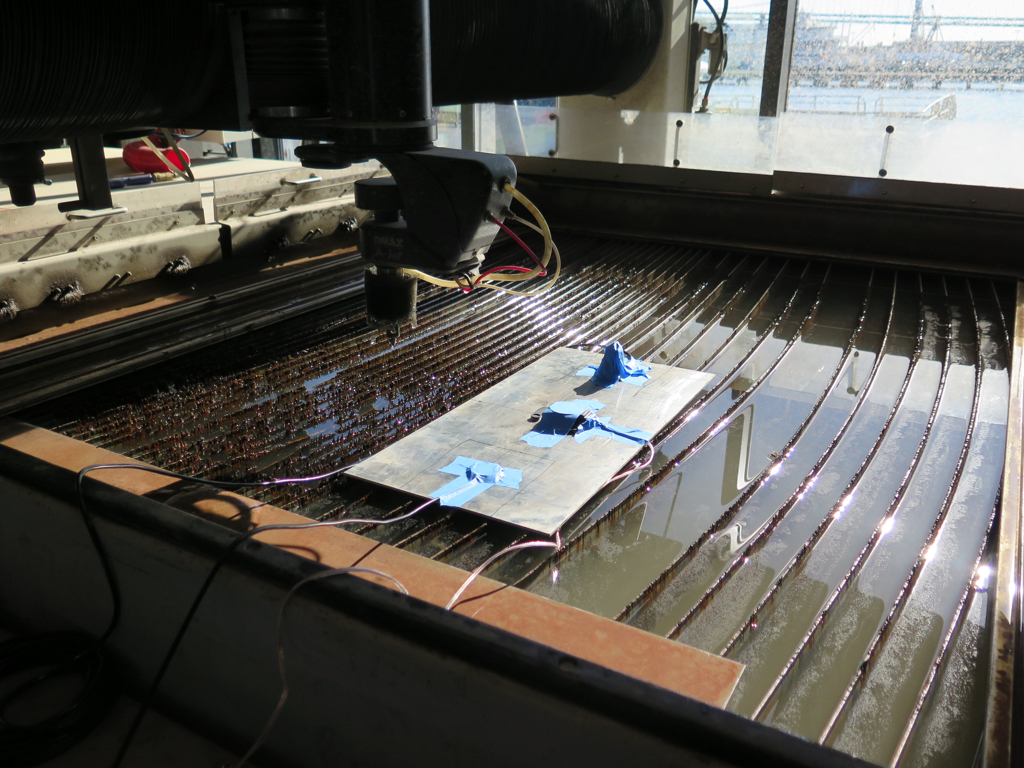

The last example I have is from the water jet, because the water jet can cut anything apart, including microphones, and I absolute love the sounds that I got out of it, but I tend to appreciate noise like that more than some other people that I’ve let listen to it. They were just, “That was very noisy.” It’s like I know, right!?

One of the projects that I worked on inside of these recordings was actually editing sounds using the machines. The narrative here is can we use machines that normally edit materials to edit sound? What I did was put two surface transducers on a piece of metal. A surface transducer basically pushes sound into a material, so it turns a single sheet of something into a speaker.

I put two surface transducers on it, two microphones on it to pick up the sound. The surface transducers are playing two different tones, and then I just cut it right down the middle. By doing that, I’ve cut the transfer medium for the surface transfers. So technically I’ve taken two different waveforms, mixed them together using the surface, I cut the surface, I cut the waveforms apart. It sounds a little bit like this:

And if you listen to this through headphones, the waves are mixed to the different channels so you can hear the stereo separation happen between the beginning and the end.

To show this I ended up making headphone holders on every single machine that I had a recording for, and made the holder on the machine that it was playing the recording for, which is one of the best and worst ideas I had here.

So that was that project. I have now been kicked out of the workshop, and exist back in the real world where all of these tools are very expensive. I would like to first off thank Autodesk for running this program in the first place. This was an amazing, amazing experience. I’d love to thank the shop and artist and residence staff for making this easy, and for dealing with me saying, “I don’t remember there being this much blood in the usage of this machine when I took the class.” And of course all of the other artists in residence, without whom I probably wouldn’t have had a project, and the amount of inspiration, the amount of help that we all gave each other was really wonderful.

Further Reference

Kyle published a collection of projects at Instructables related to the work presented here.