J. Nathan Matias: The first speaker I’d like to welcome is Ethan Zuckerman, if you want to come up. He is director of the Center for Civic Media, Professor of the Practice at the MIT Media Lab, my PhD adviser, and a longtime friend and mentor. Thank you Ethan.

Ethan Zuckerman: Hello, Nathan. Hey, everybody! So, one thing I didn’t understand until I started advising PhD students is that you actually spend a lot more time arguing than you do necessarily teaching per se. And Nathan and I had a long argument—really in some ways sort of a six-year argument. And to maybe oversimplify the terms of the argument, my argument was basically if you want to change the world, you need a good underlying theory of who you’re gonna influence and how you’re gonna influence them. And unless you have that, don’t worry about how effective your techniques are.

Nathan’s basic argument was, “Great. Agreed. Useful to have a theory. But unless you can actually measure what you’re doing, how do you know that your passionate, well-meaning action makes things better instead of making things worse?”

And when you argue for six years you sort of end up at a point where you realize you’re both right, and it’s really mostly a matter of priorities. It’s really important both to be able to have some sort of operational theory behind what you’re doing, but it’s also really important make sure that when you’re sort of gunning the gas and trying to make the change that you want to you’re actually driving in the direction you want to go in.

So that’s sort of the background behind Nathan inviting me here to talk about this question of how people are using data for social change. And so before diving into some of the ways that specifically in our lab we’ve been thinking about that, I want to talk a little bit about how I… I think maybe how Nathan, how a lot of people around here at MIT think social and civic change sort of ends up happening.

So let me start by saying that when I talk about data and social change I’m not talking about Cambridge Analytica. And I’m not talking about Cambridge Analytica for at least two reasons. One is that I think generally, every time you have a presidential election someone stands up to say, “Oh it was me! It was me. I did it. I found the data that suddenly made someone unelectable electable. It was all us and we’ll take the credit and consulting gigs for the next four years.”

But the reason I really don’t want to talk about this is that I think less and less, the forms of change that are accessible to most people— Not necessarily the forms of change that are important. But the forms of change that people are often well-positioned to engage with don’t necessarily look like this:

I think that it’s becoming harder for many people to feel like they can achieve social change either through the ballot box, or through protest, which is sort of our main mechanism where when we can’t win arguments at the ballot box we stand up and show that we’re not happy about things. We failed to elect Hillary Clinton, the largest march in history brings people out into the streets to remind people that we’ve just elected a serial sexual harasser. I want to make the case that both of those methods are actually suffering as a form of social change.

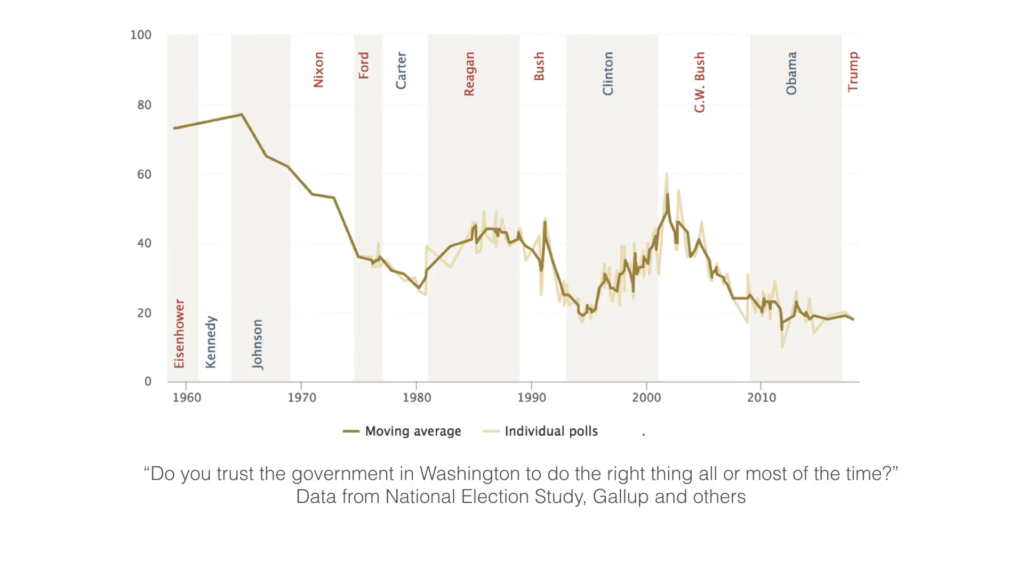

And the argument really sort of hinges on this graph. This graph is a compilation of social surveys going back into the late 1950s and it asks a very simple question. How much do you trust the government in Washington to do the right thing?

Now, if we asked that in this room, you know maybe particularly during this regime, it’s an academic institution, we tend to lean pretty liberal… You’re going to have a lot of people saying that they’re not particularly trusting. But I want you to move back in history.

In 1964, 77% of people answered the question “I trust the government in Washington to do the right thing all or most of the time.” We slipped below 20% on this metric during the Obama administration; we’ve never recovered. We’ve simply stayed there.

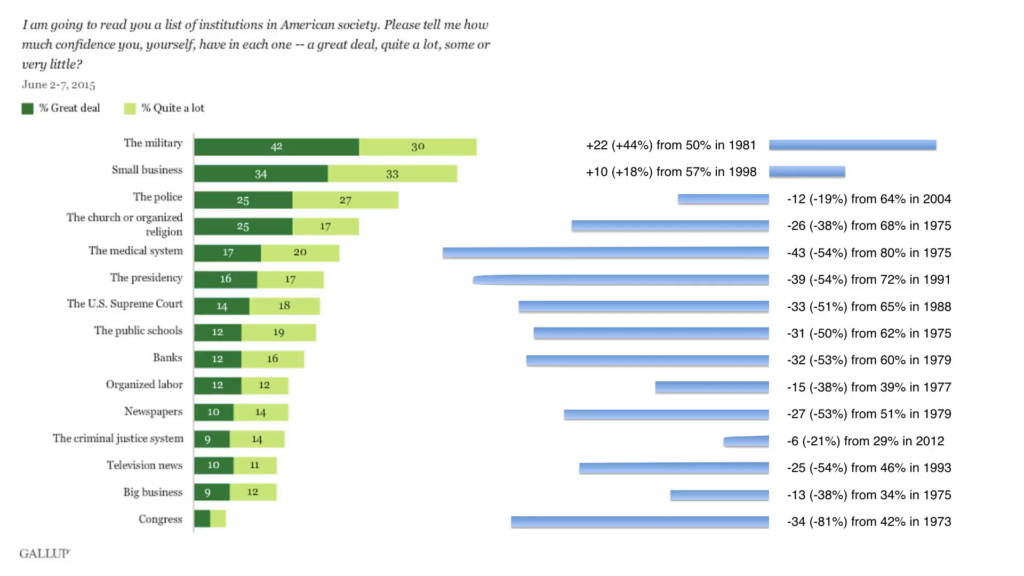

We’ve had a radical shift over the course of about fifty years in America about how we interact with institutions of all sorts. We haven’t just had a collapse of confidence in government institutions, we’ve actually had a collapse of confidence in all sorts of large institutions. When you look at how we used to feel about churches, banks, labor unions, the medical system, in almost every case if something is big enough that we are not interacting with an individual, we’re interacting with an entity, we have lost trust in it.

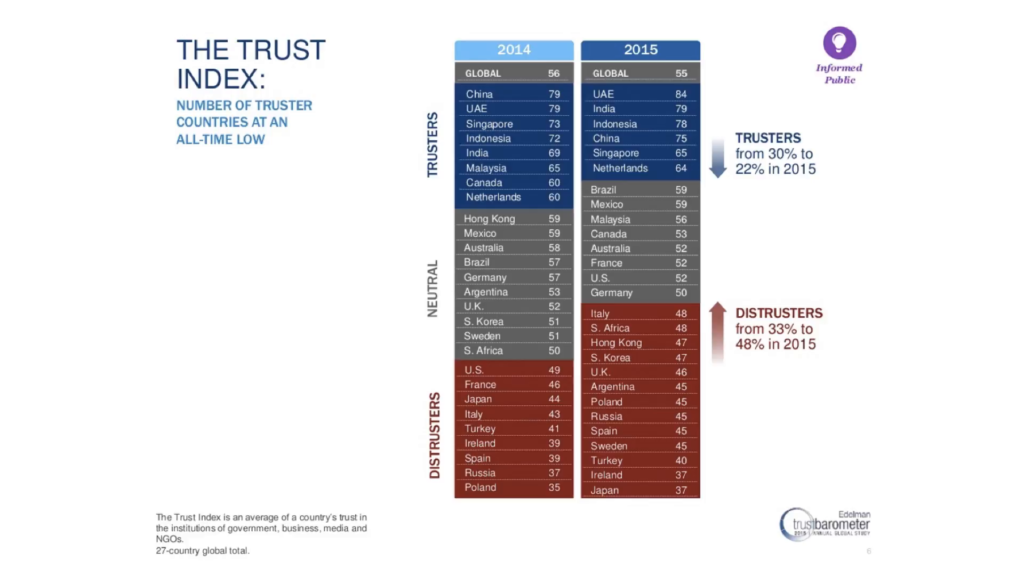

And by the way, it’s not just us. This turns out to be pretty common around the globe. It’s pretty common in high-development nations. It’s pretty common in high-democratic nations. The main nations where trust in institutions of all sorts are increasing are closed societies. So trust is increasing in China, it’s increasing in the United Arab Emirates, it’s increasing in India—which is really bad news for India. It’s decreasing almost everywhere else.

So here’s the problem with this. If you don’t trust the government to do the right thing; if you think either they’re going to do the wrong thing or in some ways even worse; that they’re so incompetent that they aren’t going to be able to make the changes that you care about, electing people to office and having that be your main theory of change? That doesn’t work anymore.

Weirdly enough, taking to the streets and protesting? That may also not work anymore. When we think about the high points of the Civil Rights Movement, when we think about the March on Washington, it was a March on Washington. It was a way of creating public pressure on Lyndon Johnson to go carry out some of these civil rights initiatives put forward under Kennedy, advocated for by King. But it was a way of pressuring a government that was able to go and make those changes. I’m arguing that some large number of people, including maybe some people in this room, don’t believe that we’re in good positions to make those changes anymore.

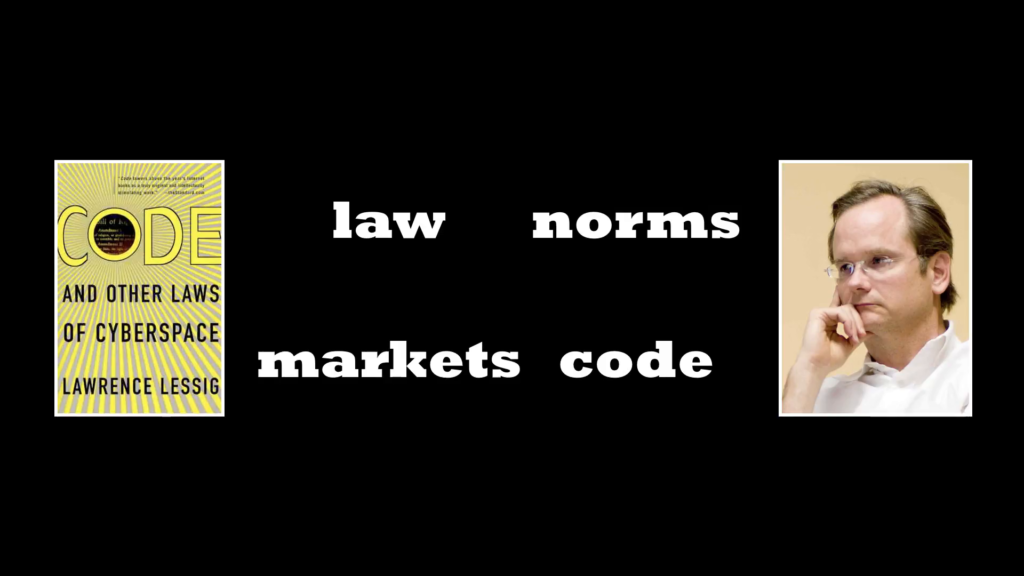

So what do you do? I went back and read Larry Lessig. I went back to a book that Lessig wrote almost twenty years ago. And Lessig says something interesting but really basically pretty simple. He says look, when we think about how societies get governed, we tend to assume that it’s by law. We pass laws and that prevents people from engaging in certain behaviors because if you engage in that behavior the police will pick you up, they’ll drag you into court, you might find yourself ending up in prison. It’s a good reason not to do certain things.

But Larry’s big point is that there’s other ways that we govern behavior. Code can govern behavior. Larry’s classic example on this is you stick a disk into your computer (back in the days when computers had those things). And if it’s an audio disc, your computer says, “Hi! Would you like me to copy this for you?” And if it’s a video disc your computer says, “I will never let you copy this. I have locked down my entire operating system to make sure this is never copied.” That isn’t law. There’s copyright law covering both of those. That’s code deciding that one behavior is okay or not.

And we also have certain behaviors that’re shaped either by markets; it’s cheap or it’s expensive to do it. Or by norms. You guys aren’t challenging me on every point by jumping up and yelling at me because there’s a pretty strong social norm that says I have the mic and I speak, and then there’s questions and answers and then you tell me what an idiot I am. But not until I’ve had the chance to get a round of applause, so on and so forth.

So what I’m interested in is what happens when we turn Lessig inside out. And I don’t mean that literally. I think that would be messy. But the inverted Lessig is a way of thinking about having multiple paths to social change. Which is to say it’s possible to make change in the world by passing laws. But it’s also possible to create new code; to create new interventions in the market; to shape norms. And that these may turn out actually to be even more powerful ways to make social change.

Anyone know who this is? Anyone recognize this person? Yell it out. Kim Davis. Why do we know who Kim Davis is? Kim Davis was a county clerk in Kentucky who refused to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples after the Supreme Court decision making it possible for same-sex couples to marry. This is why law is so powerful. The Supreme Court made a decision. Everybody in the United States other than Kim Davis suddenly said, “Okay. Now we’re going to marry same sex-couples.” One woman stood up and said we were going to do it anymore, and law ultimately made it so that she would have to do it or that someone would come into her place to do it.

Law is a lovely way to make change. It’s really clean. It’s really exacting—you make change across the board. The trick is passing laws can get hard when you have a paralyzed Congress. Passing laws has a lot to do with professionalism—having people who are used to arguing court cases, who are used to lobbying. It can feel very far from what ordinary people are able to do.

So there’s other forms of change that we’re starting to see. Don’t like climate change? Hey, buy an electric car. This starts becoming a really interesting way of taking on certain issues that we haven’t been able to tackle through law, but we might be able to tackle through markets. And if Elon Musk and Tesla’s a lousy example, think about something like rooftop solar panels. Turns out to be an interesting way of thinking about market-based theories of change.

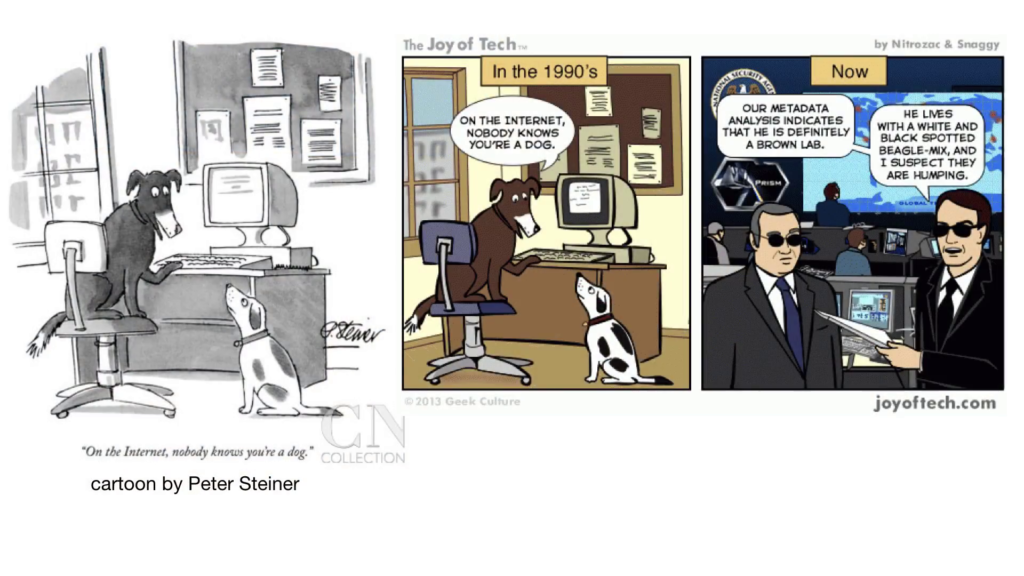

In a room like this one, always fun to talk about things like privacy and security. If you don’t like the NSA reading your mail, and I certainly don’t, we couldn’t get laws passed under Obama to get rid of this. We’re probably not going to have it happen under Trump.

But some people have done some really interesting work around normalizing cryptography and getting it baked into software that some of us use every day. And that becomes a very powerful way to make social change.

And then finally, I think frankly the most underused and poorly-understood path to social change is through challenging norms. And I think Black Lives Matter has been an amazing example of this.

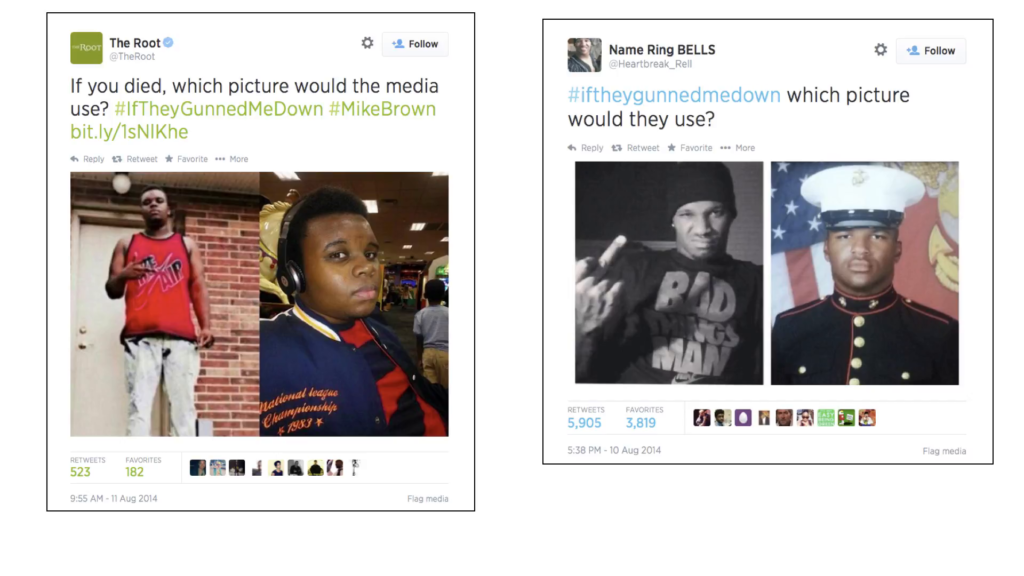

People recognize that photo all the way to left there? So that’s Mike Brown. And that’s Michael Brown’s photo taken from Facebook, broadcast on CNN and on other networks the day that he was killed by police in Ferguson, Missouri.

So, help me out here. What does Mike Brown look like in that photo where he’s wearing the red shirt? This is really hard in audiences full of white people. I get much better answers in more diverse audiences. Please. Yeah, thank you. He’s an 18 year old kid. He’s trying to look tough. He’s being shot from below. He’s flashing a peace sign; it looks like a gang sign. You know, I know that I wanted to look tough when I was 18. Same thing for him.

What’s Mike Brown look in this other photo that sort of shows up simultaneously? Right. He’s the same age in the two photos. They’re within six months of one another. But what ended up happening was that that photo on the left (also from Facebook) was the photo that anybody and everyone ended up using. The photo on the right, very rarely used.

This points to a really interesting question of how media portrays people. You started to see activists essentially saying look, if I get gunned down in the street what photo would people use to portray me?

And within three days of people starting to tweet this you had a full-scale Tumblr campaign of people putting up photos of themselves at their best and at their worst. Three days into this, you had The New York Times running a front page story on this campaign.

The way we know this campaign worked is right now if you pull up your laptop, go to Google Images and pull up Mike Brown, you will have a very hard time finding that first image. In fact, usually the only time you’ll find it is in a copy of my slides.

So moving on from this, my lab, my group of students, who Nathan’s been one of the leaders in, has been working on this question of how do we use these four levers of change? How do we use not just law, but also norms and markets and code to make change out in the world? And so I want to talk about a couple of projects that we’ve worked on in the hopes that maybe it helps us collectively here think about the rigorous data that we’re getting and the changes we want to make in our communities, whether they’re physical communities or online communities, where we go with it.

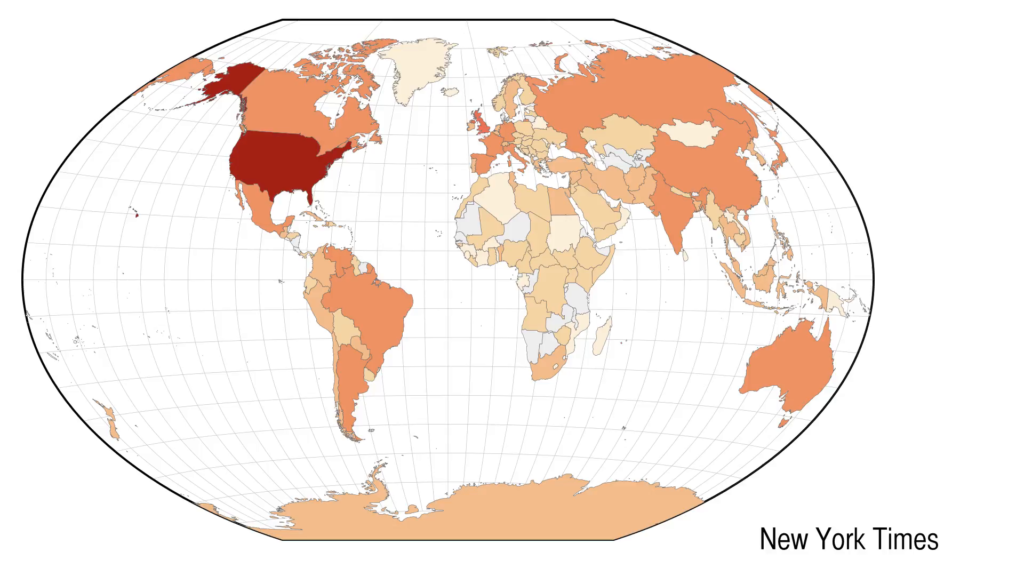

So, I spent a good chunk of my twenties living and working in Ghana, West Africa. And Ghana turns out to be a really nice place. I highly recommend spending your twenties there. If you miss the opportunity, sucks for you. But I came back to the United States and was marveling at how little news we got from Sub-Saharan Africa. And so despite the fact that I can’t really program my way out of a paper bag, I started writing code and I started essentially grabbing every story that showed up on The New York Times and throwing it on a map every day to sort of show a familiar pattern.

The New York Times writes about the United States. It writes a lot about Western Europe. It writes a little bit about big world powers like China and India. It writes basically not all about Sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe, Central Asia.

Wrote a bunch of papers about this. Predictably nothing happened. With my dear friend Rebecca MacKinnon decided that maybe what was happening here was a supply problem. Maybe if we just had more people in Africa and Central Asia writing great stories in English we’d be able to balance the whole thing out.

We started a community called Global Voices. This community now twelve years later is 1,100 people strong; puts out an amazing set of web sites in thirty different languages with news from 150 different countries. Now, amazing thing about this. It did nothing in terms of changing what The New York Times writes about. The one time we very clearly had impact was during the Arab Spring. The Times knew nothing about Tunisia, we had authors in Tunisia, we were able to be a great shortcut for them.

What it did do instead is help build up this amazing, robust community of people all over the world who’re really interested in this question of “How is my country portrayed to the rest of the world?” When people think about Pakistan, what did they think about, and is that a fair way to think about the country?

So the other thing that came out of this research is a platform that we’ve been building here for years, probably nine years now, called Media Cloud, which is basically a way of saying… This is really disconcerting. This was like there and next, and I’m confused now. [This previous comment seems to be about a technical issue but is included in case not.] But this platform lets you say, how often are we talking about Pakistan in The New York Times? And when we’re talking about it, what are we saying? We’ve actually got to the point where the Global Voices community is using this platform in part to try to build its coverage and to try to say “here are real holes in how people are talking about our country.” So we’ve ended up with a set of tools, a technical solution; a set of media, really a norms-based solution, looking at this and saying “this is how our country tends to get misrepresented in the West, can we use the data to actually put a different picture out there?”

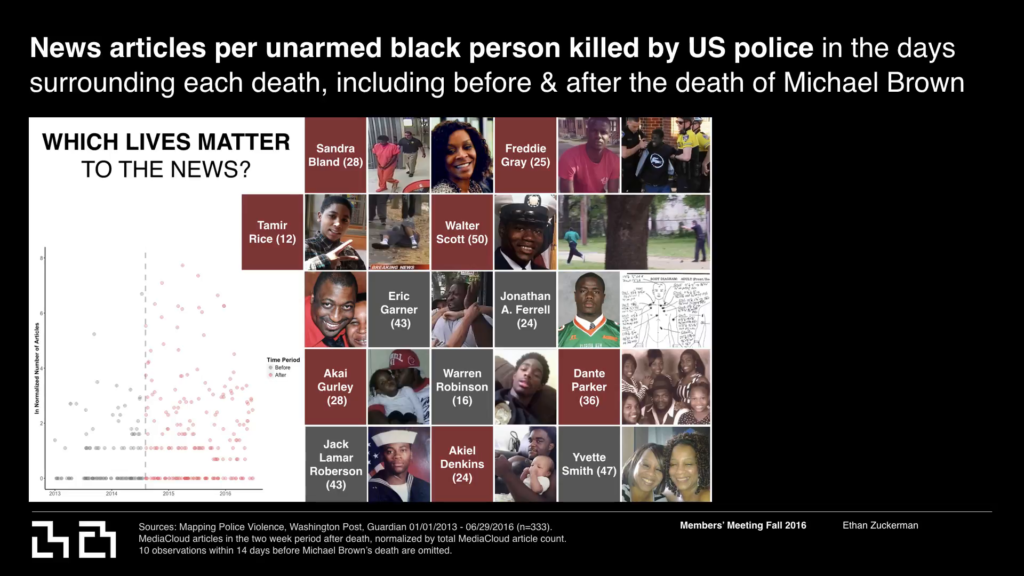

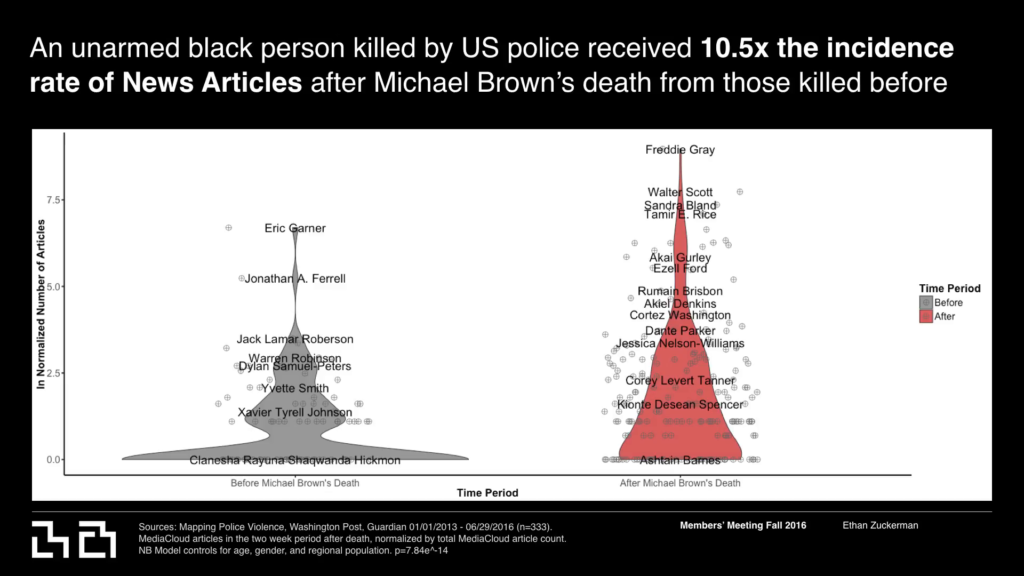

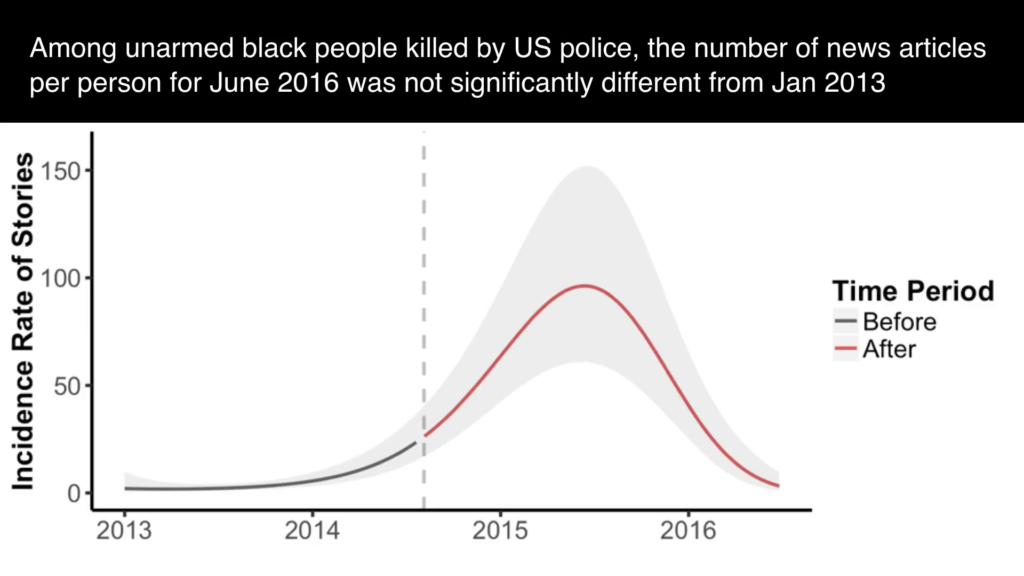

We’ve also tried using this data for some very different things. We’ve been using it to ask a question about how movements like Black Lives Matter might change what we get in the news. So this is a study that Nathan has been a key person on—we’ve worked together with about half a dozen other people on our team—looking at how media attention has been paid to various different unarmed people of color killed by police.

And what we were able to find going through this is that before Michael Brown, the most likely thing that happened if you were an unarmed person of color killed by police is that no one would write about you. Zeor or one stories is the most common outcome. Post Mike Brown, you have a much much higher chance of getting a story written about you. You also have a much higher chance of getting a bunch of stories written about you. And in fact there’s a lot of people who end up at a much higher level of media attention post Mike Brown then they would pre Mike Brown.

In fact what happens for about two years after Mike Brown’s death, you have a real shift in how the media is paying attention these stories. Not just people who end up becoming famous, but people who simply end up being reported on in their community. What’s even more interesting in some ways is that people change how they write these stories.

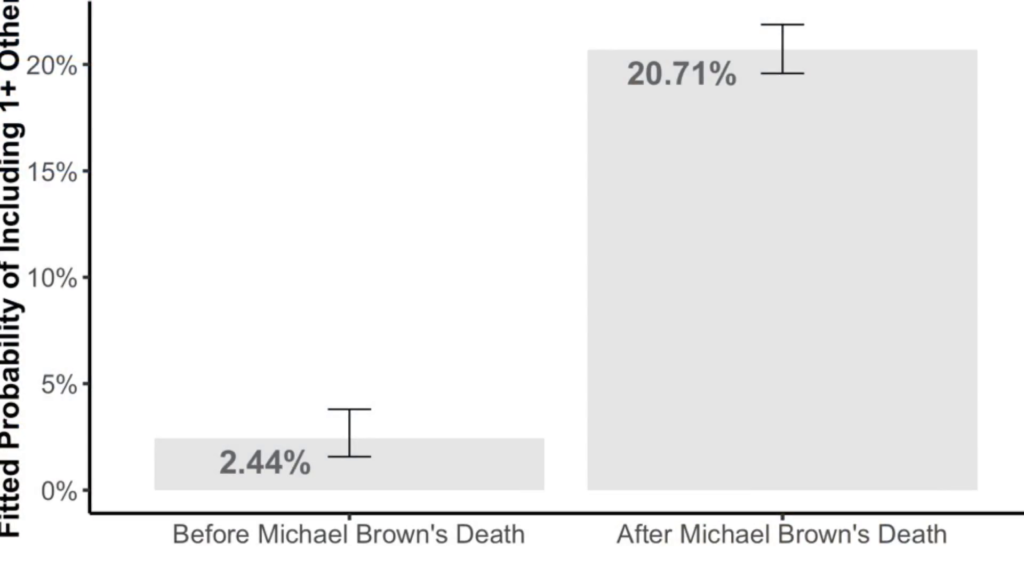

When someone was killed by the police pre Mike Brown, there was about a 2% chance that you would have the name of another victim in that story. Post Mike Brown it rises to 22%. That’s a pretty clear signal that what’s going on is people are saying, “This person was gunned down…like Mike Brown. Like Freddie Gray.” It’s a way that reporters turn this individual story into part of a news wave, a whole phenomenon of what we’re talking about at the same time. And this looks like a strategy that activists can use to try to figure out how they frame these stories by saying this is yet another instance of this ongoing trend that we have to take a closer look at.

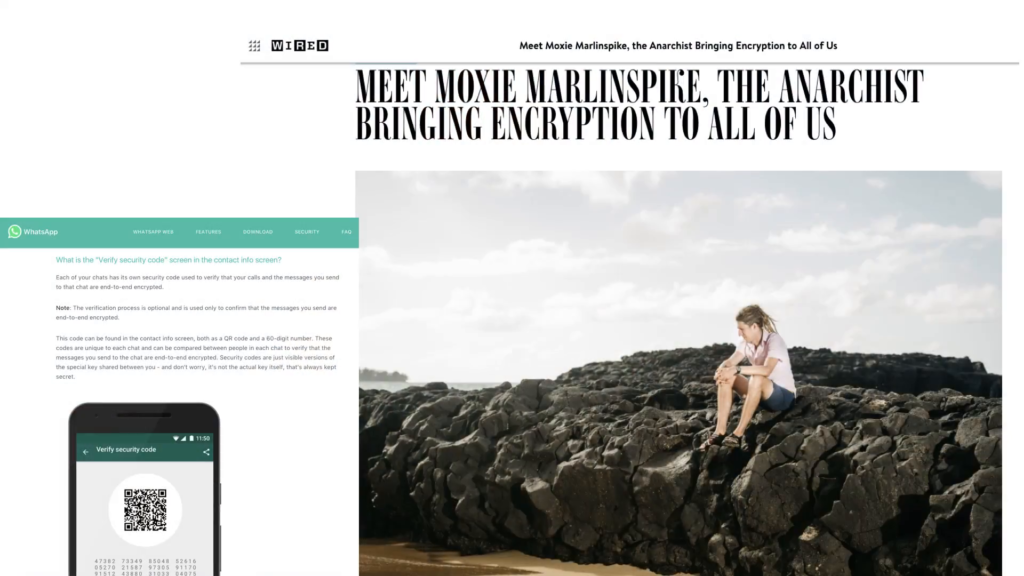

And now we’re seeing people who we weren’t necessarily working with using our tools, using our data, to come in and apply this to different things including Sophie Chou, former graduate of the Media Lab, going out and using this tool to inquire about MeToo and to look at the ways in which the MeToo movement has focused very heavily on perpetrators and on celebrities, but not so much on the people who actually built [inaudible] the movement.

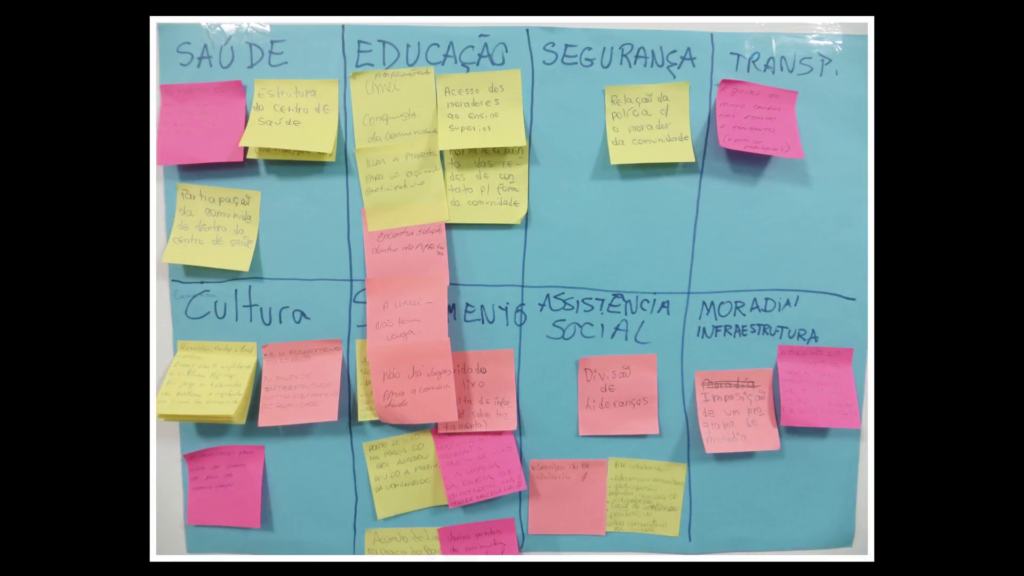

But look, data for change doesn’t just have to happen on the screen, it can happen in some very different communities. We’ve been doing a lot of work in communities—favelas—in Brazil. This is a community in Belo Horizonte where we’ve gone out and worked with community groups around this question of what happens when you get to go collect your own data, grab the data out of the community that you care the most about and find ways to visualize it and think about it.

And so in this community of Santa Marta we went out and asked people “What are the problems that you most care about?” And the problems that we ended up finding were problems that we didn’t expect people would tell us about.

I ended up spending a very hot day climbing staircases with these two gentleman. And the reason for this is that when you’re in a favela, there aren’t a lot of streets, there are a lot of staircases. And what people really cared about in this community was corrimão, stair railings. Because if you were an elderly guy climbing up the stairs and you fall, you break your hip. And so what this community really wanted from the city of Belo Horizonte was railings. And so by going out and mapping where these staircases were, mapping which ones were dangerous, mapping which ones didn’t have railings, they suddenly had a pool of data that they could use to go and approach their local government.

So this project has now become a very large thing, it’s called Promise Tracker. Where it has actually caught on the most is high school students monitoring the quality of their lunch. And before you laugh too much about this let me say, high school lunch is protected explicitly in the Brazilian constitution. How many calories you get. What the quality of it is. This is actually in the constitutional document, because it’s really important in a middle income nation that people go out and get fed. And what happened was high school students took this and started essentially saying, “Look, we are being fad crappy food.” Who cared the most about this? The local public prosecutor, who went and used the data to go after the people supplying the schools to say “Was this corruption?” Or was this solvable problems like the fact that many of these schools don’t have refrigerators? So you bring the meeting on Monday and by Wednesday there’s nothing else that you can serve people.

This idea has now gone national. There’s people in communities all throughout Brazil who are running this. And what seems to work the best about this is that when you have this artisanal data; when you have collected it yourself; when you’ve gone out and framed the question and asked it, this is the stuff that you most want to make change about.

Last thing I’m going to talk about is the data project that we’ve been working on the last year or so. This is a project called Gobo. And Gobo is basically a way of asking what information you’re encountering out in the world. Gobo is basically an aggregator that you got to control. And so you link your Twitter to it, you link your Facebook to it, and you start getting these posts in. And unlike on Facebook, you can find why you’re seeing what you’re seeing.

Gobo for each post will say “Here’s why we filtered this in or out of your feed.” And it gives you a set of controls that you can look at and basically say, “You know, honestly I’d like people to be a little nicer. So I’m gonna slide my ‘rudeness’ filter over. And frankly I listen to too many men. So I’m gonna slide the ‘gender’ slider over.” Or actually use the “Mute all men” button which may be my single favorite button on the Internet at the moment.

But what this is really about is giving you a chance to experiment with and interrogate how algorithms are shaping the world around you. And so we’re now collecting data on what do people want to do with this? Is this a way that people would want to encounter social media? Is this something that someone like Facebook should be offering sort of built into their tools?

My point in all of this (now that I have talked to long as Nathan is reminding me) is that we benefit enormously from having the data to link to our intuitions of what’s important and our theories about how we want this to be used for change. Without the data, it’s very hard to move the lever. Without the lever and an intelligent choice of who you’re trying to influence and how, it’s hard to use the data in a way that’s effective. So, I know that it’s been useful for Nathan and for me in the different projects that we’ve taken on. I hope some of these ideas are useful in sort of thinking about the various different ways you’re trying to use data for change in your own communities. So, thank you.

Further Reference

Gathering the Custodians of the Internet: Lessons from the First CivilServant Summit at CivilServant