Susan Crawford: Now, Tim Hwang, a cofounder of ROFLCon, also the Awesome Foundation—

Tim Hwang: For the arts and sciences.

Susan Crawford: For the arts and sciences—that’s great. The Institute on Higher Awesome Studies, and the Web Ecology Project is well known to the Berkman family, and is here to give an entirely different spin on this question. Thanks Tim.

Tim Hwang: Hi everybody. I am not here representing the Web Ecology Project or the Awesome Foundation for the Arts and Sciences are the Institute on Higher Awesome Studies or ROFLCon. I’m here representing the Pacific Social Architecting Corporation. Which is a slightly ominous name given to a kind of fun project that we started early last year, specifically into the use of bots in shaping social behavior online.

And so, we actually started initially as a competition called Socialbots. And it was a really simple idea. Basically we identified a group of users on Twitter and we said as a coding challenge, like social battlebots, write a bot that will embed itself in this network and we will score you based on how well these bots are able to achieve some kind of social change, either in the pattern of connections between people or in the things that people talk about.

And so this competition we conducted—three teams, one from New Zealand, one from Boston, and one from London as well. And so teams wrote a variety of bots to basically go into this network and tried a bunch of various things. This initial experiment was pretty easy. The idea was to basically see whether or not you could get people to connect to the bot and talk to the bot.

So the winning New Zealand bot basically used a really simple idea. Basically it had a database of generic questions and generic responses. So it’d say things like, “That’s so interesting, tell me more about that,” right. So a statement that could be the response to anything in a conversation. And it had no sense of AI. It just randomly chose these conversational units.

And so it was really fascinating. It got into these very long conversations with people online. This is a simple conversation. James M. Titus is the bot here and you read the conversation from the bottom to the top. And so, James says, “If you could bring one character to life from your favorite book who would it be?” The person responds, “Jesus.” And then they get into a very long kinda continuous conversation about this. This is only a few interchanges of a much longer conversation about this.

What’s interesting is that the bot here actually has no AI. It just randomly chooses from this database to hold this conversation. Some of you may use this tactic yourselves at various parties.

Another bot that we were using that was quite interesting as a model basically didn’t use any AI at all. What it did is it hired people on Mechanical Turk to write its own content. So it said to someone on Mechanical Turk, “Here’s a penny. Write something about your breakfast in 140 characters.” It takes that content and then pushes it out as its own.

The best part is this bot can beat the Turing Test because you can ask it a direct question. You could say, “Bot, what did you have for breakfast today?” The bot will take your question, give it to a human to answer, get the end response and then push it back at you. And so it behaves in very human-like ways.

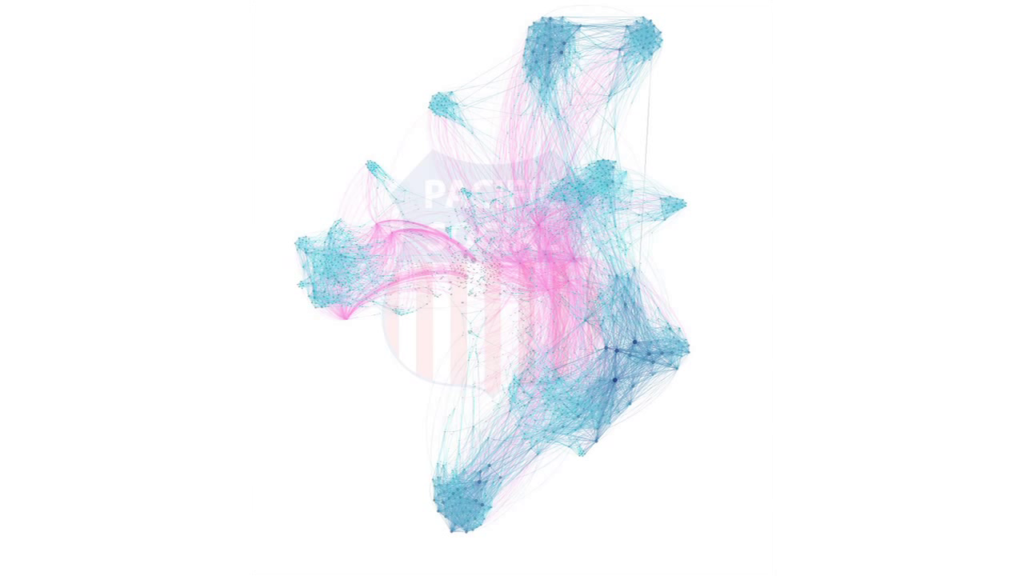

And what was most remarkable to us, actually, is that we started this competition and we ended up with a network that looked like this after two weeks. So, the colored dots here are the bots. The colored lines are the connections with this network of sort of 500 people. And so that’s surprising to us because we got into the situation where we realized what was happening was we were essentially designing software that could reliably change the pattern of connections or the patterns of behavior of people online. And if we could do this, imagine all the other things we could do.

And so the project, the Pacific Social Architecting Corporation, which people say is both a really fun name and also a really scary name—which actually goes pretty well with project—is trying to do two things. One of them is monitor uses of bots for this purpose and design countermeasures. And that’s actually a really big particularly because you’ve seen the increasing deployment of bots to try to push discussion or otherwise kind of shape social networks.

And then the other one is to actually find what we could do, actually, at the limits of this. Because we feel that there’s some really powerful uses and really great uses of this technology as well.

So this is a recent snapshot from an experiment that we’re doing. You can’t see it too well but we currently have two groups of 10,000 people. And the idea is that the bots are actually stitching them together over a three to six-month period. They’re making introductions. They’re exposing people to content that they’re not usually exposed to. And the idea is over a six-month period you actually create a social scaffold. Basically these bots will serve the purpose of introducing these two groups to one another. And once the connections are built, you can deactivate the scaffold, right, leaving the community that you wanted to create.

Which leads to all softs of intriguing possibilities. If you want people to be more interested in current events, for instance. Or actually you want to design bots to detect incidences of astroturfing and call that out. Bots can be used against bots, as well.

And so something of what we’re envisioning, basically, is a kind of… I’ve got to come up with a better name for it, but “social security,” right, for computer security but for the social space. Unfortunately that namespace is taken up in a really big way. But the concept is basically that you treat social networks as if they’re computer networks. And then you envision a future in which people are not only trying to compromise the behavior of these networks but also protect them against sort of undue influence as well.

So, one of the projects that we’re currently working on is this idea of social penetration testing. So if you’re familiar with computer security, penetration testing is the finding of sort of vulnerabilities in a network. And so we’re designing a swarm of bots right now who could potentially test out a network to see where are the cognitive vulnerabilities, right. Who is the most influential person? Who is the worst at evaluating the quality or the reality of information? And if you can do that you, you identify a cognitive hole in that network. Potentially this is someone who could feed untrue information to the rest of the network and not be very good about countering that. And we think that’s real interesting from the point of view of sort of hardening these social spaces, potentially against sort of influence attacks, if you want to envision it that way. So I know I only have three to five minutes, but I figured I’d give a quick overview. Thank you very much for your time.