Kyra Maya Phillips: Hello everybody. I’m really happy to be here but my stomach I don’t think is very excited about it. But, I left my son back in Australia with his father. So I’m excited about it but I’m also very nervous about being away from my family. But he always wants to come with me to everything. You know children kind of feel left out all the time.

When I tell him that I need to go to the chemist he’s like, “Fine, go.” I told him I was going to a chemist in Brighton, England and he didn’t believe me. So he said he really wanted to come to Meaning. He couldn’t come. So I was wondering if I could just film a short video of you saying, “Hello Leo,” on three so that he doesn’t feel left out and I can come back as a star parent. Thank you. One, two, three. [audience says, “Hello Leo,” in unison]

That’s great. Thank you. Thank you so much.

So, I am actually very touched by the topic of this conference, which is a rather special word, a very important word, “meaning.” And I think particularly during this time when I feel like everybody wakes up and comes face to face with meaninglessness itself. And it feels good to be part of a group of people who are trying to bring back that… I don’t want to say hope, but…I guess realistic and…non-cynical, because I think that it’s cynicism that really is breaking everything down at the moment. So I’m very excited about that topic.

And in thinking about this talk today it really struck me that everybody has different values. You know, what we see as important, as meaningful, differs from person to person. But you know despite these differences, the quest for meaning is always there. Throughout a human life it never disappears. Running through like a thread through through the story of every human experience is that very familiar question you know, “what does this all mean?”

And it’s a fundamental aspect I think of what makes us human and what makes it so hard but also so interesting to be human, kind of this instinct to question the meaning of our own existence seems to be the catalyst for so many things that make life worth living in the first place. So you know, music, art, literature and so on. So the results of our sort of quest for meaning are all around us. But I think that meaning itself is actually extraordinarily elusive. Throughout our lives, I think it seems to do, at least in my experience, a little dance, you know. It comes and it goes. It’s a very frustrating performance. And even when meaning is present in our lives—so when we sit down and we think and we feel its presence, it likes to keep an element of mystery, you know. It’s hard to see even when it’s around, and it seems to prefer the dark.

So I’ve spent about four years exploring the dark side of innovation, trying to convince people that there’s actually a lot that we can learn from those who work in the unseen corners of the world. You know, so-called misfits. Pirates, hackers, gangsters, con artists, pranksters, ex-prisoners.

And from this exploration into the world of outlaws and undesirables I’ve found over and over again that they too look for meaning. So when a Somali pirate is hijacking a ship off the coast of Somalia, he is often asking himself why he’s doing that. When a young drug dealer is trying to find a way to secure a few corners, he’s building a narrative that attaches some sort of meaning to those actions. When a copycat is replicating a pharmaceutical, there is a story there about why she believes that her mission is a worthy one.

So we are not the only people who seek to draw out meaning from experience. You know, everybody does that. We’re certainly not the only ones. So I want to give you just a brief example of that. I mentioned Somali pirates, and actually a few years ago I interviewed a group of Somali pirates. And piracy in Somalia started as very unsophisticated business in the early 90s. And it came about as a response to foreign trawlers who were stealing the fishing stock that people on the coast depended on for income.

So a group of fisherman got together and they would see the ships that crossed their shores and, sort of an opportunistic sort of affair, and they would hijack them and then they would split the spoils according to how much each fishermen had invested in the operation or either split the spoils equally as well. And the government of Somalia collapsed in 1991 after a very brutal civil war, so the Navy and coastal police wasn’t able to repel the illegal fishing and also wasn’t able to repel the response to it as well.

So then something happened. A civil servant noticed that this was going on, and he thought that it would be a good idea to scale this small, lo-fi cottage industry. And he approached investors, and I quote with “a very good business idea,” and he founded an organization called the Somali Marines. And he recruited employees, many of them the original pirates on the coast, provided them with military-style training, and established what is today known as modern Somali piracy, which is the capture for ransom of large commercial vessels with the use of motherships as bases across the ocean.

And the pirates began to command ransom payments, you might’ve seen this in the news over the years, that were in the millions. The average haul was $2.7 million US dollars, and since the first known hijacking in 2005 over 149 hijacked ships for about an estimated $385 million, and with links all across the world as well. So it turned from a very small cottage industry into quite a large, international, well-organized organization. Pirates even employed lawyers, and negotiators, and bank note checkers, and even sort of small local economies would spring up on the coast while negotiation for ransom payments were on going, providing the hostages and the pirates with water, khat (which is a narcotic leaf), and food and mobile phone services.

But here’s the thing about Somali pirates that I was more interested in beyond the economics of how the movement scaled. The initial pirates, the original pirates, who were fishermen, were being very genuine when they said that they became pirates because of the attacks on their fishing stock, and that they were only safeguarding what was originally theirs to begin with.

But the truth of the story was lost relatively quickly. Most of Somalia’s pirates lack a history in fishing. It’s a marginal activity in Somalia, it’s not part of Somali diet, it’s actually looked down upon as a way of making a living. But every single pirate I spoke to said the same thing, you know. They said, “We are the protectors of our coast. We do this because of the attacks on our stock.” They were all on message.

And what this shows me is an incredible PR machine that is ensuring that the meaning of what they are doing isn’t lost, even if it’s untrue. So the pirate entrepreneurs like many of the entrepreneurs that we come across in the world that we operate within every day think about how to build culture, how to recruit and retain the best employees, and how to give them a sense of mission that goes beyond monetary gain, even though that’s the ultimate goal. You know in our world we talk about how to find purpose. Why do we sell iPhones and and iPads and Macbooks? Because we believe in beautiful products and we want to change the world with them. Well then, when you’re pirating you also need that “why.” So misfits, what I found, provide an answer—that why as well.

There is a story that really stuck out for me when I was thinking about the talk today. This this is Duane Jackson, and a he’s a guy that I met a few years ago. He lives near here in Hove, and we met many times and we had very long conversations about his life. Duane grew up in children’s homes all over East London. He was kicked out of his house when he was 11 years old, kicked out of school when he was 15. And he was actually on the verge of being institutionalized when a child psychologist assessed him and in his report concluded that he would either be a master criminal or an extremely successful businessman.

And this conclusion became sort of a foreshadowing of a future that he was yet to shape but not immediately. So in his early twenties, Duane fell in with a drug trafficking ring. And he was struggling to pay his rent and his bills and most significantly for him, a £400 debt to his own mother. So he agreed to traffic drugs from England to United States and he was arrested in Atlanta in possession of six and a half thousand tablets of ecstasy.

But let’s back up a little bit to Duane at age 15, before the drug trafficking and before the stint in prison. He spent two and a half years in prison in England. And while he was sitting in the dining room of a children’s home that he’d been living in, he noticed an old ZX Spectrum computer. He taught himself to code with it. He found the manual. And he became obsessed with it because it provided him— It was a challenge but it also provided him with a certain level of consistency and certainty that had been missing from every aspect of his life.

And he actually continued coding while he was in prison. He used to code with pen and paper and then call a programmer on the outside, and then they would debug the code together. And so instead of prison being this place that kind of stunted and limited his development, it actually became a place where he would gain really hugely important skills and perspective. He said for example that in prison you notice everything around you because you have so much time to sit still. Ninety percent of your time in prison is bloody boring, so everything takes on an additional meaning and every little detail begins to matter.

So for example, he said you can make hot baked beans on toast by cutting a plastic bottle in half, putting water in it and heating it with wires from a stereo, and therefore heating the beans. And then using the same heat to toast the bread on the metal wires that you find under prison mattresses. So these materials aren’t useless. They’re ways to cook a meal.

Now, the forced stillness of prison provided Duane with kind of the sort of perception that he needed to find meaning in the things that seemed most meaningless, really. So perhaps it isn’t as elusive as we believe it is—as I said I believe it is when I started talking. Perhaps it’s everywhere but we are moving at a speed that isn’t really allowing us to take it in.

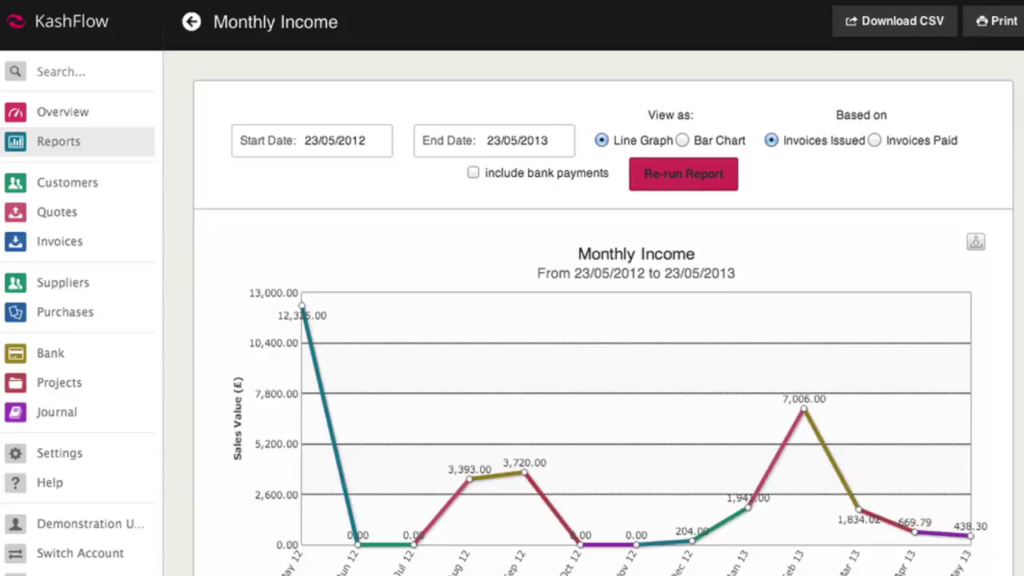

So when Duane made it out of prison— (I have to speak very quickly because I have about a minute and a half left.) When he made it out of prison he used this keen sense of observation that he had sort of honed through imposed stillness. When he was released, he started up a company called KashFlow. Has anyone heard of it? It’s great. And it’s an accounting platform. Before that he began working as a freelance web developer, and he stumbled onto a problem. He didn’t have a way to organize his invoices in a straight way. This was the early 2000s and the software that was around was counterintuitive and confusing. I’m sure people here remember the time when you had to buy software on CDs and everything was annoying and impossible to deal with.

So he kind of thought, and he said, “What’s going on around here? Can I create something better?” So at the time the business model in the industry was for software to be built for the desktop. And the perceived wisdom would’ve been to follow this path. But Duane was a web developer. And he didn’t have money to hire desktop developers, and he didn’t have the skill to do it.

So using kind of the attention to detail he thought, “I have web hosting space. And I also have this ability to program online. So what can I do with it?” So instead of building a competing desktop program, he created his own accounting software. And this was on the cloud. And this was 2005, and the cloud was not the thing that it is today.

So by paying attention, by simply noticing what was available to him like you make hot baked beans on toast, he avoided falling falling into the trap of following the herd. You know, his business was a success and he sold it in 2013 for quite a huge amount of money but that’s not the important bit. To me, the beauty of this whole thing is that Duane arrived at this way of accessing software and became a pioneer of this way in which we do everything today are virtue of his life experience. Life experience that taught him the tremendous benefits of just stopping for one second.

In closing our conversation—and I’m almost done—Duane told me something that remains etched in my brain. He said, “At no other point in your life do you get to press pause for two years and think about where you are and how you got there. And I was lucky,” he said, “that I had that opportunity. I was lucky.”

And he’s right, you know. When do we create the space for reflection? And for stillness. You know, we’re analog beings, but we run at a relentless digital pace and I think it’s important to ask ourselves what the costs of that is.

Just to close, there is a wonderful book called The Art of Stillness by Pico Iyer, and he describes stillness in such a beautiful way. He said, “To me the point of sitting still is that it helps you to see through the very idea of pushing forward. Indeed, it lead you into a place where you are defined by something larger. And if it does have benefits, then they lie within some invisible bank account with a very high interest rate but very long-term yields to be drawn upon at that moment, surely inevitable, when the doctor walks into your room shaking his head. Or another car veers in front of yours. And all that you will have to draw upon is what you have collected in your deeper moments.”

That really struck me. All that you will have to draw upon is what you have collected in your deeper moments. Everything else is just noise, really. We don’t have to be thrown into prison or dragged into desperate circumstances to choose how we derive meaning from experience. If we learn how to stop and reflect, it’s possible—hard and we might not always want to—but possible, to find purpose and meaning in everything that at first glance might seem like nothing. So I hope this was helpful. Thank you, and I apologize for going over time. Thank you so much.