Jay Springett: So before I start, I’m just gonna say that this is going to be a bit of an infodump. And I’m going to be going quite quickly. So if anyone’s got any questions in the Q&A, please let me know. Because I’m going to be going quite quickly to move the conversation on. I’m going to be making some sweeping generalizations about things. So, I thought I’d start off with a bit of a smaller topic, so let’s weigh in.

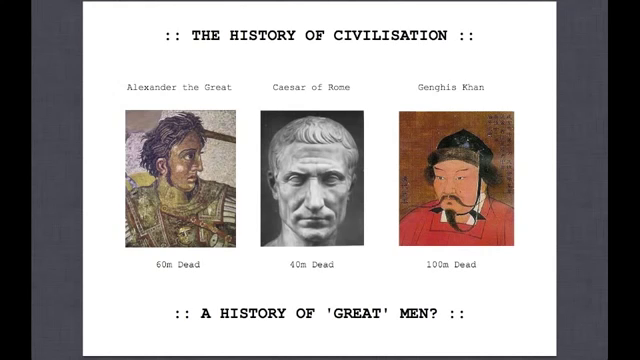

There are a number of things throughout history of culture that societies have used to tell stories about themselves. And whether these are memes or whether they’re myths is a question. But one of these, when talking about the history of civilization is the history of great men.

So Alexander the Great created the Byzantine era. Caesar of Rome civilized the Gauls, built the roads, and united Europe. And Genghis Khan created his empire and opened up the trade routes between the East and the West

Dan Carlin, who’s an amateur historian and podcaster, talks about these men as “historical arsonists.” And what he talks about is there’s the great men as an entity, and then there’s the number of people that they killed. And as you move forward in history, the number of people that they killed drops out of human memory. So when we look at this, Alexander the Great killed 60 million people. Caesar of Rome killed 40 million people. And Genghis Khan was expected to have killed about 100 million people in his lifetime. So this is the story of great men of history.

There’s a number of these myths, such as man’s dominion over the earth, which is a meme of colonialization. And the way social Darwinism has been adopted by neoliberalism to express meritocracy. And then of course there’s technology as progress, which is one of the memes of capitalism. “Science discovers, technology executes, and man conforms.” I don’t think you can get a better quote than that. So history is written by the victors, and it’s also rewritten by the revisionist historians. This is why “Luddite” is used as a pejorative. Because to question the technological doctrine of progress is to question the system and the cultural meme of the day. But here we are.

I’m concerned that the current level of discourse around politics of technology is held very much in the same level of critique as fair trade.

Fair trade does nothing to address the fundamental structure of the supply and goods environment. Instead it tends to pierce down and build an ethical supply chain from beginning to end. This completely disregards the fact that the entire system is unethical and does nothing to really fix anything. So the question why is your cell phone covered in blood is a question that goes far beyond the manufacture and delivery of the device.

So history of technology is the history of civilization. The primary concern of all humans throughout history has been not dying. So the way that we have coped to mitigate this risk of not dying is by building infrastructure.

Tap, turn, and flush. These are the three interactions that every day you have with infrastructure around us. The rest is hidden. The key point is that whilst we interact with the tap, turn, and flush, the infrastructure and the technologies involved in infrastructure around us are part of a vast network of interconnected dependencies, and they’re increasingly more and more hidden from us.

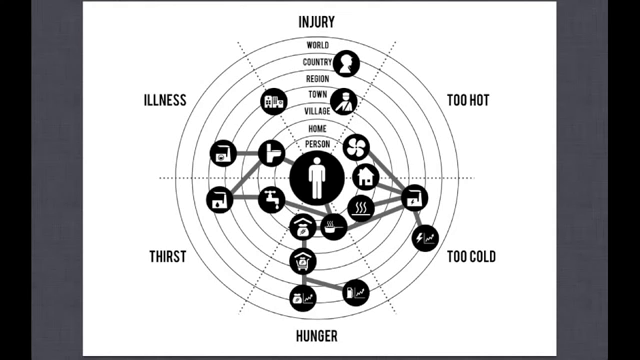

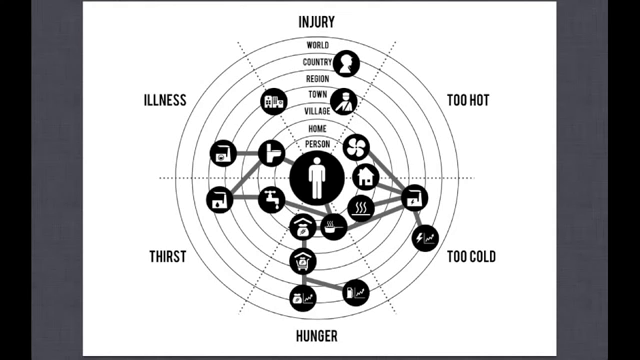

So this is what’s known as a Simple Critical Infrastructure Map, by Vinay Gupta. And it is an attempt to map the infrastructure around us against the six ways to die. So too hot, too cold, illness, injury, hunger, and thirst. These are the six ways to die, and the map with the individual at the center is an attempt to mitigate those things.

This is a typical Westerner. So if we take cooking, which is in the hunger section of the graph, it’s related to the energy power station and the energy market. It’s related to the water and the municipal water system, and also sanitation systems in the city. We’ve also got how and where you store your food. And you’ve also got where your food comes from in terms of the shop and how it gets to the shops. And those things are also related to the global food markets and the fuel markets.

So this in the very crude sense is The Stack. What we’re talking about is the stack of technologies that keep us alive, and also allow us to communicate and transport. So the Stack is something… This term allows us to map hidden terrain of infrastructure that keeps us alive, and allows us to speak about it conceptually.

At this point what I’d like to do is throw out a term for this, and that is “stacktivism.” And it’s a term that I think is useful in order for us to conceptualize this vast interconnected network of technologies that we interact with on a daily basis. Because you can’t have a conversation about something that remains unseen. So beginning to have this conversation, I think is something that would be really useful.

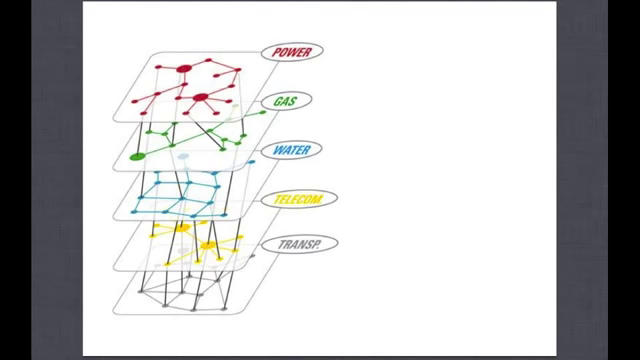

So just to quickly cover the Stack. So this is a risk and resilience analysis graph of infrastructure; this is actually in New York. And you can see how the power grid relates to the gas grid which is also related to the water grid. But they are also connected and interdependent on each other. So this also in the crudest sense is a visualization of the stack of technology.

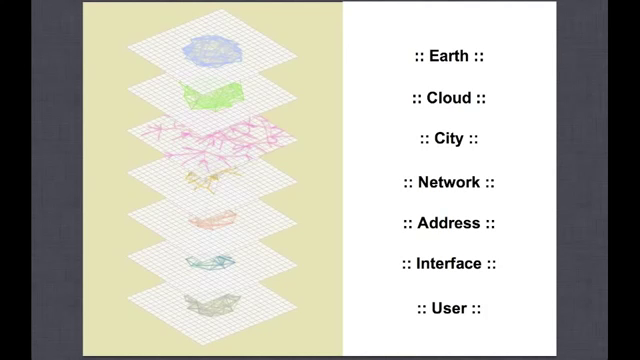

There’s Benjamin Bratton, who’s writing a book called The Stack. He gives us some theoretical language around infrastructure which takes us from the user up to the Earth level. So every interaction they have, either with the Internet or with any kind of grid, goes through these seven points and then back down again.

And then of course, the SCIM map gives us a rough map of these technologies and how we map it to the individual in its relation with not dying.

So these new economic geographies mean updating the politics. One of the things that the Luddites understood was that certain technologies internalize certain ideologies. And this is both in terms of the way they are constructed but also the way that they function. So the history of how the Stack is built and by who is the history of civilization.

So the municipal model of infrastructure built by the Victorians. Consider the water grid, for example. You build the water plant outside of the city, you control it, and then you connect everyone to it. This very much reflects the administrative practices of Victorian times. Control over the electricity, gas, and water and our relationship to these is an important question. Because it’s worth nothing that these things—the water and the gas—were centralized far before they were privatized.

In this context we should question the neutrality of the Stack, and the power and influence that it has over us. The same goes for terms that to seek to obscure infrastructure, such as “the cloud.” This term is in fact a term for a shed for the computers just off of the M4. So the political history of each layer tells us something about the time at which it was made.

Now, our relationship with the Stack. The SCIM map puts an individual at the center of a simple model, and that is the six ways to die. Not dying is the principal concern of most of the people on our planet, and that is something that we should at least recognize. So the personal and political relationship with the Stack is having control or access over the means not to die from. It’s having the means to heat your home, it’s having the means to carry the waste away from you house, and it’s having the access to clean water.

Most political thought has centered around human needs, which are in pure survival terms shelter, water, fire, and food. There’s no healthcare in that model. Whereas if you were to negate the ways to die, then that conversation is there.

The current critique of global capitalism and the left in general is of Marx. Marx’s interest in factories and land is all pre-infrastructure and it was written in the time when trade and colonialism, and war, were much closer together. Marx didn’t see this stuff coming because it didn’t exist. There were no grids in the time of Marx. He doesn’t give us a reference point in this regard. At the time of Marx, you got your money and then you went and bought the coal to heat your house, in your house. This ability to keep yourself alive is only evident when it stops working such as in Hurricane Sandy.

So, what happens when you lose control of the means not to die from? This is a picture of Athens. You can’t really see it that well, this is a picture Athens from the winter. And there’s a haze of wood smoke across the city. And that’s because due to austerity policies there’s huge taxes that have been put on oil and gas. So people people have gone back to burning firewood in wood-burning stoves. There are a lot of ecological issues and health issues with this. There’s a lot more efficient ways of gaining control of the means not to die from.

So who controls the Stack is one of the 21st century…that should be our critique of the Stack. It’s not necessarily who owns the robots. Instead it’s who controls the Stack.

Thinking about our relationship to the means of not dying in the Stack give us far more greater leverage points than the traditional approach of the wage relation. And it’s worth noting that the politics that build a given infrastructure don’t necessarily die until the infrastructure is gone. It is the relationship with the means not to die from that should be politicized, because this is an approach that we can all share globally. Thanks.