Hey, y’all. Good morning.

I really really love it when a conference has a one-word theme, because that’s right in my wheelhouse as a dictionary editor. I feel very comfortable with a single word at a time. I can work with this. Did anyone else read the logo as “rebel lion?” I was like, “That is an awesome name for a band.”

Obviously lexicographers are the first people you think of when you think of rebels, right? Dictionary editors. You can see that we’re always the first on the barricades when the time comes. And of course this is what we think of when we think of rebellion. Guns, shouting, fire in the streets. But in my professional opinion, I think that we can broaden the definition of rebellion. Really, rebellion is just trying to make the world match your understanding of it. You believe things should be one way, the world believes things should be another way, and you’re going to change the world to match your understanding. Why force something that doesn’t fit? Why not just make a square hole?

So if we think that the rebellion changes the world, does it really matter what the time scale is? It doesn’t have to be an overnight overthrow. It can be the steady remaking of the world through pure force of conviction, like water wearing away stone. We have slow food, we have slow fashion, why can’t we have slow rebellion? Many things that we think of as being revolutions, like scientific revolutions, were not the kind of sudden overthrow/lots of shouting rebellions.

This is what Max Planck said very famously about scientific revolutions:

A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.

Max Planck

They don’t triumph. You just have to outlive the bastards.

So especially when you’re thinking about the revolution, the rebellion, that comes with a new idea, sometimes a slow rebellion is the way to go. And of course when you want to change the world, it helps that the way that I’ve wanted to change the world affects one very very small part of the world. I wanted to change how dictionaries were made. This is how people really think dictionaries are made:

You take the language, you grind it up, and then you have this kind of consistent sludge of dictionary. That’s not very entertaining to me, and I don’t think it’s very helpful to people, so here’s the way that I think the dictionary should be made. They should represent every single word in the language, no matter what. And that usage is what determines meaning; meaning is determined by how people use a word. And that yes, that means every word, even the ones you don’t like. If you want to argue with this, I’m really happy to argue with you at the party tonight, but I should warn you that I don’t drink, and if when we argue about this you’re drunk and I’m sober, I’m going to win. But it’s okay because if you’re drunk enough you won’t remember losing. So that’ll be fine.

If you were here at PopTech in 2008, you might be having a moment of déjà vu right now because I was right here on this stage when we announced wordnik.com, which is the dictionary that I have been making. And I should probably make some kind of Inception joke right here. I thought about wearing that dress again. But I decided to just show you our throwback logo.

You can hardly tell that it was done in a style I like to call “half-assed Illustrator.”

Wordnik has been going on for six years, since 2008. The people at Poptech were the first people to see our alpha version, the first people to get to try it out. I think that if one human year is like seven dog years, then six human years is like forty-two Internet years, right? Six years on the Internet is a really long time. The advantage of a slow rebellion is that it gives you time to learn things while you’re changing the world. If you have a sudden overthrow rebellion, there’s not really time to reflect. But six years is a long time to reflect.

I try to learn something every day, not matter how dumb, and I like to tweet it. “TILT” means Thing I Learned Today, and this is something I learned back in August that I have not yet had the opportunity to put into practice:

https://mobile.twitter.com/emckean/status/499700052156514305

So I try and learn something every day, but I think that the most valuable kind of knowledge is that which you acquire through noegenesis. Noegenesis is a fantastic word, and it means “The acquisition of new knowledge from observation and experience, and from inferring relationships between known things.” So with six years of Wordnik on the Internet, a lot of what we’ve learned, what I’ve learned, are some assumptions that got validated.

My favorite thing that we’ve learned is the assumption we went with going in is that meaning of a word equals usage of a word, and you can infer meaning from usage. So STEAM, which stands for “Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Math.” You read that sentence, you know what STEAM means, you don’t need a traditional dictionary definition. You’re good. You can move on with your life. I want to point out the citation for second example. John Maeda was saying, “Oh, you need the A for Art to turn STEM (which is Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) to STEAM.”

Another thing I’ve learned that made me really happy is that people really do love words. Sometimes when you really love something you just extrapolate and believe that the universe really loves something. But it turns out lots of people love words. There have been 158-some odd thousand words that have been marked as a favorite on wordnik.com. That’s roughly three new favorite words an hour for six years, which is pretty cool.

And people like to collect words. People have made more than 48,000 lists on Wordnik, and those lists comprise 1.7 million words. 1.7 million words were considered important enough for people to put them on a personal list.

We also found out that people need to add words to other things. So the Wordnik API has been called [1,805,761,975] times. In fact, just backstage I was talking with Brent, who helps run this thing, and he’s actually made something with the Wordnik API. He has this little cool tool that puts his word of the day on his own blog. Learning all this was great, and learning all this was gratifying, but there were a lot of things that we didn’t know going in.

One of the things we didn’t know is what things were going to be easy and what things were going to be hard. Larry Wall, the inventor of the programming language Perl, which is the first programming I did any kind of professional non-school coding in, and I should really embroider this on a sampler:

Easy things should be easy, and hard things should be possible.

Larry Wall

Another famous Perlism is that “there’s more than one way to do it,” which I think is also a great mantra for slow rebels, right? If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. He also said something that I used to have on a sign above my desk that I had photocopied from one of the Perl programming books that said, “We want you to acquire the three chief virtues of a programmer, which are: laziness, impatience, and hubris.”

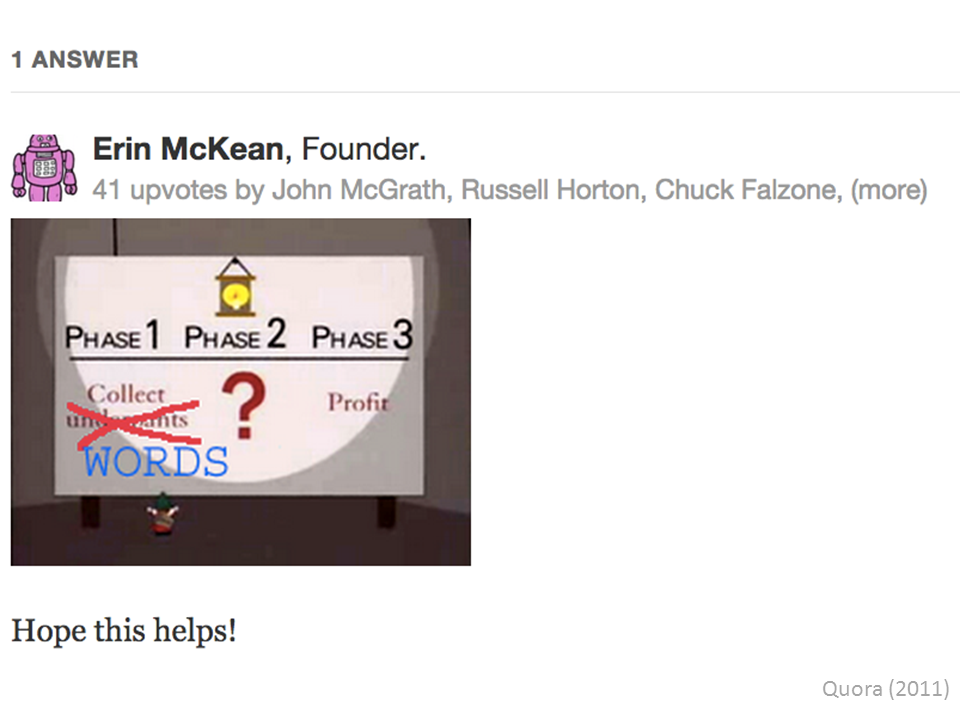

So, we found that a lot of things that we thought would be easy were easy, we found that a lot of things we thought would be hard were in fact possible. But the hardest thing, the thing that I was the most uncertain of when we first started Wordnik was this Quora question: How does Wordnik make money? Because when you have a startup, that’s one of the things that you’re trying to find out. What’s the business model. This is answer I posted to this question:

I don’t know how many of you are South Park fans, but they had an episode where there were these underpants gnomes, and this was their business model. This is my most upvoted answer on Quora, by the way. Only two of those people who upvoted were actual Wordnik employees at the time. But it turns out our thesis was that if you knew a lot about a lot of words, that that data would be valuable. And it turns out with Reverb Technologies (we’ve made the Reverb iPad and iPhone reader app) that you can use a word graph to build a content discovery platform that helps you discover articles based on your interests rather than your demographics. It’s been downloaded nearly half a million times, and people use it to read about five to eight times longer than they do in competing apps.

So when you know all the words, you know a lot about aboutness, and you can help people find what they’re really interested in. So yay, business model, right? This works great. So I like to say that when we started Wordnik, we were trying to make panning for gold, finding out information about words, more efficient and more scalable. And we thought that that data would be gold, that it would be very valuable.

And we were right. But it turned out to be even bigger than we thought. So we scaled up panning for gold. That was great. But in the process what we basically got was hydroelectric power. It wasn’t so much the gold that was important, but the process. The process of ingesting and analysing and building a word graph out of billions of words was very powerful.

So that’s great, right? Rebellion accomplished, industry disrupted, product market fit, business model found, customers happy. Well… When this slide came up yesterday, did anybody else kind of feel like this was a message to them personally?

It was like, “Yay, the universe! It’s trying to tell us something.” So I’m very happy with Reverb Technologies. I’m really proud of what we’ve built. We built a fantastic technology that helps publishers reach millions of people with relevant, useful content. It makes readers happy. It makes writers happy. But that actually turned out to be easier than I expected, so it’s not the hardest thing. The hardest thing for me is how can I make a 120,000 Wordniks happy? And how could I make that number ten times bigger?

Because really, the English language belongs to everybody. The English language is something that we all share together. The only reason it exists is because we all agree to understand each other when we speak it. That’s what the English language is. So today I’m happy to announce that in order to further our mission of making as much information as possible about as many words as possible available to as many people as possible, that Wordnik is going to become a not-for-profit corporation.

And this feels hard and scary, but I’m so happy about it because it means that I can ask for help. I can ask people who love and want to be part of the English language to join me to make that information available to everyone. This URL is live right now. I thought people love words, there are so many favorite words on Wordnik. Wouldn’t it be nice to let people adopt a word, just like you can adopt a highway? And when you adopt a word we can help spruce it up a little bit. The charismatic words like “serendipity” and “callipygian” will help support the words that nobody likes, like “impact.”

This is an alpha alpha alpha. Once again PopTechers are going to be the first people to get to try out something new with Wordnik. That’s live and you can reserve your word today. John [Maeda] already grabbed “design,” so sorry, folks. And let me know what your ideas are. What you’re interested in, what you’d like us to do, because again the English language belongs to everyone.

And by making Wordnik open, non-profit, we can do all the things for which there really is no business model. If anybody knows an excellent business model for writing etymologies, please let me know. Everybody loves them, nobody wants to pay for them.

So I hope to be back at PopTech in 2020 in another few years to give you another update. Thank you so much for your kind attention. I also want to thank Joey specifically for all his work with Creative Commons, because all of these images were Creative Commons-licensed from Flickr. This presentation itself is Creative Commons-licensed, so if you’d like to use all these same slides to give a completely different talk, please let me know. I will make them available to you.

Thank you so much.