Sarah Marshall: Okay, next up, Nanjira Sambuli. And the title of her talk is “REACT to Close the Digital Gender Divide.”

Nanjira Sambuli: Or in other words, how to make technology less shit, picking up from where we just started. Yeah, I think I can see the room so I can ask this question. How many here work on connecting the unconnected, in some shape or form, to the Internet, to the Web, to digital technology? Be proud about it. Raise your hand up high. I love it. About half the room.

Another question: How many here work on that issue from say, the private sector, or identify as private sector? Hands up high? Don’t be shy, don’t be shy. No lynching. Alright. We have maybe one percent.

Civil society, when my civil society people at? Come on. I expected more. Yeah. Alright, another half or so.

Question: Anybody here from government? Safe space. We have one, yay! Welcome to the party. It’s good to know who I’m speaking to about this issue.

A bit about myself. I come from Nairobi, Kenya. Place in Africa, great place. And five or so years ago, I got really interested in how technology was being adopted. If you know a bit about Kenyan technology you’ve probably heard of M‑Pesa mobile money platform. Ushahidi actually started off in Kenya as well. And there’s a great energy about what technology could and couldn’t do.

Now, at this time I was dead bored studying math. Which in hindsight is very useful in the world of AI, but hey. I’ll cross that bridge when I get there. But I started spending time with innovators to better understand so, what were they creating and for whom. How was that going to scale up? How could be also contribute to the world?

But two things became very clear for me early on. One, it’ll take more than innovation. Two, women were a minority in those spaces. They were not being seen, they were not being heard, they were not basically the first people speaking up on that.

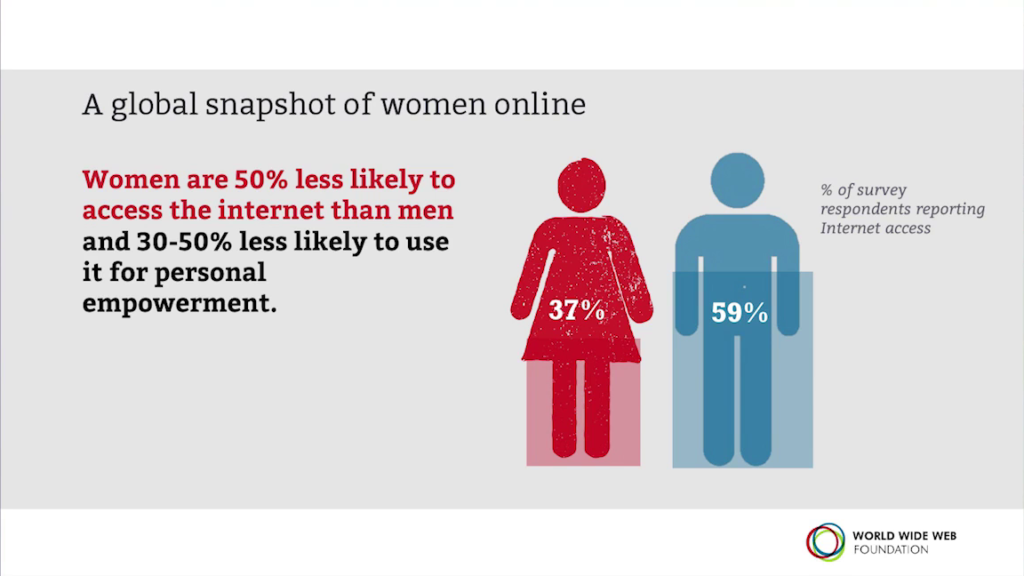

And so, fast forward to what I do now, which is preoccupy by myself with how do we make sure the Web is for all. And I found that research globally is pointing out that women are 50% less likely to be connected to the Internet. And not just that. Even when they’re connected they’re 30 to 50% less likely to use it for personal empowerment. So much for Web For All, right?

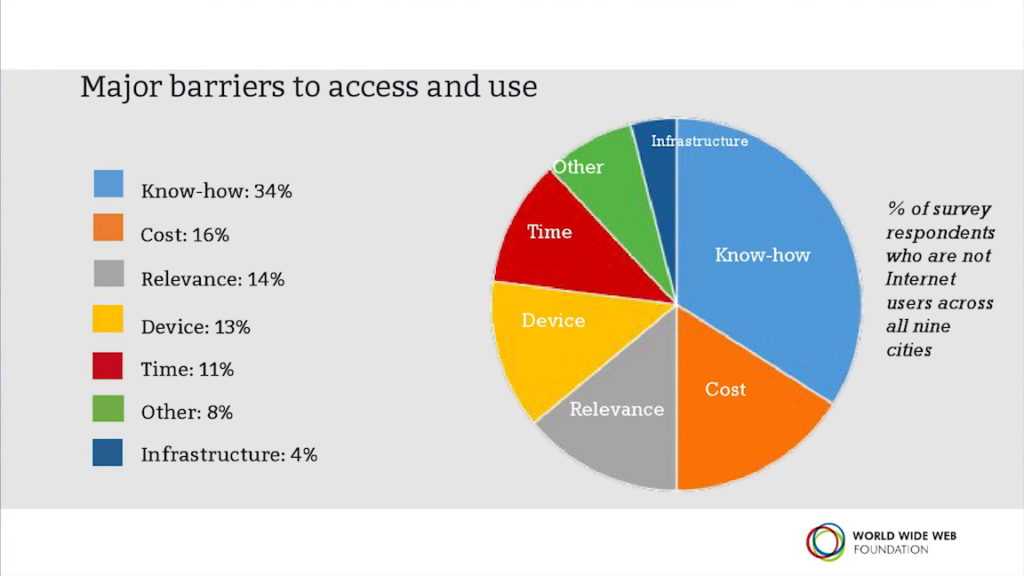

And some of the reasons being cited for this: lack of know-how, scarcity of time, and relevant content. Prohibitively high cost of devices and data. And also the chilling effect once you’re online—social, political, legal—because there’s no place, no country, no space for women to just be to speak their minds.

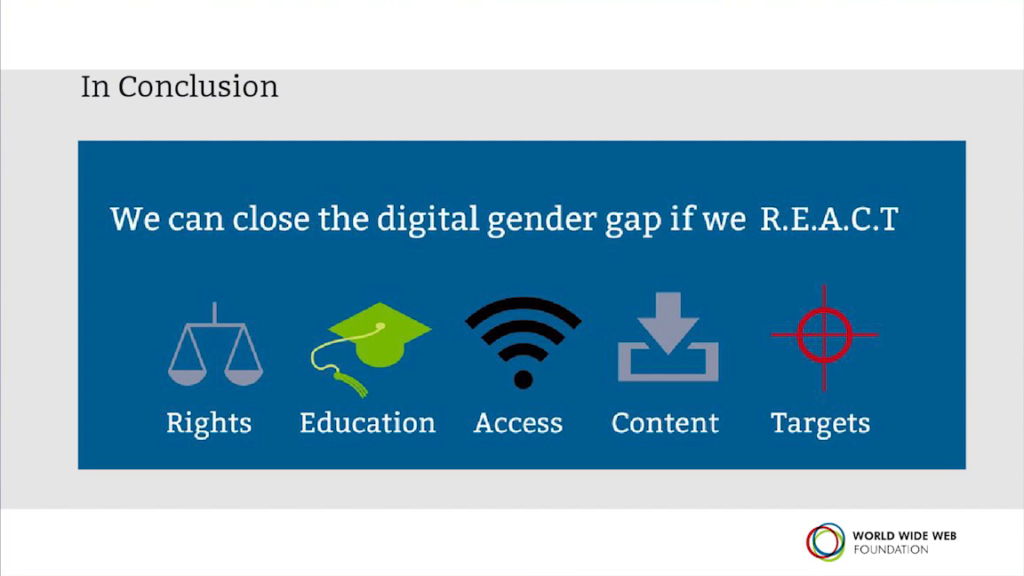

And so I found it was not just unique to Kenya or Africa. It is something that is being seen across the world. And so the question is obviously what should we do about it? We are all trying to connect the unconnected, so what does that mean? We do need to react to the fact that this is a problem. But I mean something different by REACT. I mean that we need a focus on five things: rights, education, affordable access, relevant content, and targets that help us measure progress.

Now, great that we have at least one government person in the room because the question is, if I ask many of you here to name great initiatives you know that are trying to connect the unconnected, they’re probably civil society-led, or private sector-led. But what are governments doing? Where are they? At least we have some representation in the room. But how are they reacting to the digital gender gap?

Some may ask why should they be reacting? And I know sometimes when you bring up the word “governmental policy” eyes go half mast. But stick with me here. Because governments have to be involved from the get-go. Because this issue is primarily a result of policy failure. And so it stands to reason if we’re building solid foundations for a healthy Internet, those same people have to be involved. Governments have to be involved. Policy has to be involved. But we also have to be involved.

Now, why governments also have to be involved is research is actually showing that countries that have very clear strategies and targets in their ICT policies to increase Internet penetration have higher adoption rates and lower costs for connecting people. It’s just what it is. And what policies do in that sense is they help us ensure success of any long-term plans to connect people, to address the digital gender gap, and everything under this REACT framework’s sun, if you will.

And that way, we’re able to identify investment mechanisms for actually achieving those goals, but with very clear targets identified. So who’s not connected, and how is it that whether it’s government, whether it’s private sector, whether it’s civil society, we will be working collectively to connect them.

Now, since of two billion people worldwide who aren’t connected, 50% are women, those policies have to go another step. They have to be gender-responsive. It’s a buzzword but I’ll give you the meaning of it in just a second. It essentially means one thing: that when you’re designing plans, when you’re laying out roadmaps for connecting people, you take into consideration the different challenges of all groups in society. But also the specific challenges that are keeping women from being connected. And in so doing we’re just creating equal opportunities for men and women alike to be connected.

I mean guys, I don’t know about you but wouldn’t it be nice for once if there’s something in this world that we discover as humanity that actually gets off on the right foot? So that we’re not always dealing with inequalities or geographies, inequalities of women? It is the space of policy to do that, and I passionately believe that we can get this right with ICT policies.

So let me give you an example, because that sounds nice— I’ll give you two examples, actually. Nigeria. Country in West Africa. Most populous country in Africa. By all intents and purposes has an ICT policy that is gender-responsive. But this is what I mean by that: on what they’ve listed as their plan for the next four years, they talk about monitoring the number of women and girls who are not connected and even providing incentives for private sector actors and civil society to train women on how to use the Internet—women and girls, for that matter.

Great, right? Only problem is (and there’s always a “but” with governments) they are doing this in an ad hoc manner. So the language on it—on paper, perfect. But when it comes to the actual roll-out it’s all ad hoc. And then unfortunately what that has done is any initiatives are reaching those who are already connected. So a waste of great resources happening right there. That policy’s coming up for review next year and my question has been so what will they say has been the progress made? People remain unconnected, 50% of women are still offline. How will they know how over the last four years they’ve fared? If there’s anyone here in the room who works in Nigeria, how will you know how your contribution fed on to a bigger thing of actually achieving universal access?

Another interesting example is Costa Rica. The government there is using a tool called the Universal Service Access Fund, which is essentially money the government has to connect the unconnected; simplest definition. And they’re doing something interesting with theirs, which is they are providing subsidies for low-income households to get fixed Internet bandwidth and computers. Now, approximately 95% of the people who benefit from that are actually women. Why? Because they understood something: research was showing that in their country, the relative cost to connect was higher for women, especially female-headed households in low-income neighborhoods.

So, see? It can be done. And they can expand on that and go beyond fixed Internet bandwidth to mobile broadband and other ways to connect people, and then maybe achieve universal access in our lifetime.

So, that’s examples of where we are, a sort of state of play with governments. Well I’m sure you’ll ask me, “Well y’all are not government people so what does that have to do with anything?” But at the end of the day, everything that we are doing needs a solid foundation. This healthy Internet we need needs a solid foundation. That solid foundation is called policy. Hate it or love it, guys. It is what it is.

So, government absolutely have to start being pushed to do better. And it’s also our job to make sure that we advocate for them to have those policies, as I mentioned, those basic principles that they adhere to, that help us also figure out how our collective efforts are making sure we achieve universal affordable access. It’s about ourselves continuing to do what we do. We are innovators in this room, the people who are building stuff. But, sorry to break it to you, we will not entrepreneur our way out of bad public policy—not forever, anyway.

So if you’ve been able to moonshot—I love that word. If you’ve been able to moonshot with your innovation to connect people, good for you. But not all of us are going to be able to moonshot out of it. And if we keep ignoring the policy layer, what’s going to happen is governments effectively become blockers for what we are trying to achieve here. I don’t know about you, I’d like to minimize the resistance that we have to deal with. So how quicker can we make sure that we put governments to task?

That is one aspect. But, when it comes to specifically to women, all of us have a responsibility to make sure our programs, our efforts, our initiatives, take gender considerations from every step of the way. That means from planning, to programming, to monitoring. And it means that you have to involve gender experts, every step of the way.

Now, I come from Kenya, yes. I may be able to speak about some perspective about this in Kenya. But I will not be able to always speak about it for Africa. So that means you have to find different people from different areas. I may be able to talk about my suburban background and whatever that might be as a disparity to connect. But I’m not necessarily the best person to speak about an urban poor woman and the challenges they face. I may be able to speak to them, but I also know my limitations. So by extension, and especially for those who work on a more global outlook, I will not fulfill that diversity quota alone. You have to find the people who understand the communities you’re trying to work for. [applause]

I hope if nothing else, the community that has gathered today here understands that point. Because we are diverse people, even if we come from very complex backgrounds. And that means we have to invest time to appreciate that diversity so that these efforts we’re all putting in actually achieve what we’re here to do. We need this Web to be for everyone. It can be done but there’s some fundamental principles we have to adopt.

But I also tie that back to the role of governments. Because at the end of the day, when your great resources (currently) run out, if you’re running a program in Country X to connect the unconnected, when that funding runs out or your interests have to go elsewhere, how will that program remain? What happens to those people—they’re real people. You started introducing something but there’s no exit plan, sustainability plan…whatever buzzword works for you in that context. That is the role of governments. And fundamentally, if we want a Web for all, it has to be a public good. And a human right. And so we cannot exonerate governments from their job. Thank you.

Sarah Marshall: Questions, or comments?

Audience 1: You spoke a lot about accessibility. [inaudible] touch on your research or knowledge about the empowerment portion where you know, you had said 50% do not have access but 30 to 50% do not feel empowered.

Nanjira Sambuli: Yes.

Audience 1: I was wondering your experience there with improvement.

Sambuli: It’s not unique to the Web per se. It’s also to do with communities and how they allow women to just be. So the Internet or the online space is not fundamentally different. Because once I get there, if the moment I just say, “Hello world,” and they’re like, “Woman, shut up.” [shrugs] You’re like— We learn the same things and just transfer them to technology. That’s just one aspect. And there’s also cultural barriers that over time have made it feel like— Many women feel like it’s not my space to comment on politics or issues that are affecting us. Let me just exist in my little woman’s corner and do my little women’s stuff.

So there’s a lot of the offline also replicating online, and we have to make sure that in everything that we’re doing we factor that in. So empowerment sometimes is like a [?] word, but it’s also like women just not knowing that they can use the Web to make money, in some cases. Sell their wares, that kind of thing. But it’s also because of other issues that have existed that have predated the Internet, but also being ported to that space.

Audience 2: Speaking as a person who comes from a country with a government with problems, and speaking to a person who might have a government with problems—

Sambuli: Mine, too.

Audience 2: Right? How do you work with the government to do the right thing when you see them doing a lot of wrong things?

Sambuli: Whoo, yeah.

Audience: I’m struggling with this right now.

Sambuli: Yeah. That’s a whole other talk, by the way.

Audience 2: Yeah.

Sambuli: But. It’s stuff like… One of the things I’ve found especially for those of us who come from countries that rely on aid or some other development corporation, there’s a need to also speak to spaces like these where somebody might go and advise a country, a government, that wants to give money to another country to embed those principles. That way we’re able to Trojan horse some principles that on our other end we can find.

The other thing I’ve found, and it’s really really difficult and it’s very subjective, is engaging, conversing with those people. I don’t know about you but most governments have fossils of people who don’t understand what technology is. I am not the first person during this MozFest to stand here and say that. So we have to find the grace to engage with them. And it’s a lot of work. It is a lot of energy. It is not for all of us to do. But we have to start doing it.

So there are many strategies, and I’d be happy to talk more about strategizing. It’s not a one-size-fits-all approach, but we all have to try. Because if nothing else, we pay taxes. We do.

Marshall: Okay. I think we’re set. So let’s thanks Nanjira again, that was fantastic.